Executive Summary

Mandatory exit exams are in place, or will soon be, in 27 states. Students must pass them as one condition for receiving a standard diploma. Because the standard diploma is considered a property right, states must carefully consider the opportunities that students have to pass graduation exams. Federal legislation has resulted in increased emphasis on the participation of all students in statewide assessments, including those with disabilities. Attention also is being paid to the use of accommodations during exit exams, and the extent to which these exams are designed to be accessible to the greatest possible number of students. There have been several court cases in which states were challenged about the extent to which they allowed appropriate accommodations.

While universally designed and accessible tests and appropriate accommodations are important to ensure that exit exams give students the opportunities needed to earn a standard diploma, they alone may not be adequate. As a result, a number of states provide alternative routes that students can take to earn a standard diploma. The purpose of this study was to investigate the alternative routes used by states for all students (including students with disabilities) and those that are allowed only for students with disabilities. In a previous National Center on Educational Outcomes survey, state directors of special education (or a designee) in 16 states indicated that an alternative route of some type was available. Our study involved obtaining information on alternative routes from these state Web sites, and then verifying that information (and adding to it when verifiable information was received).

Of the 16 states that we studied, 10 had an alternative route for all students (including students with disabilities) as well as alternative routes just for students with disabilities. Three of the remaining six states had alternative routes for all students only, and three had alternative routes just for students with disabilities. We examined the specific nature of the alternative routes, including the eligibility criteria, who initiates the alternative route request, who makes decisions, the process itself, and the comparability of the alternative route to the standard route and found significant variation. Perhaps of most interest was our analysis of the comparability of the alternative routes and the standard routes to the diploma. Although we used only broad criteria for our analysis, it is nevertheless noteworthy that 71% of the alternative routes for all students were judged comparable to the standard routes, whereas only 35% of the alternative routes for students with disabilities were judged to be comparable. This tendency of many states to identify non-comparable routes for students with disabilities leads to questions about the assumptions and beliefs that underlie the alternative routes.

Based on our analysis of states’ approaches and an amalgamation of varied results from many other studies, we propose a basic assumption that should underlie the development of any alternative route—regardless of the target of the alternative route: Because the standard diploma is an important property right, the alternative route to this property right should uphold the same principles as the standard route to the diploma. This assumption leads us to make several recommendations:

-

States with an alternative route to their standard diploma must provide clear, easy-to-find information about the alternative route.

-

The alternative route must be based on the same beliefs and premises as the standard route to the diploma.

-

The same route or routes should be available to all students.

-

The alternative route should truly be an alternative to the graduation exam, not just another test.

-

The alternative route should reflect a reasoned and reasonable process.

-

Procedures should be implemented to evaluate the technical adequacy of the alternative route and to track its consequences.

There is much that states have to do to open up opportunities for students with disabilities to demonstrate what they know and can do through ways other than those typically used in large-scale assessments. It is a worthwhile endeavor if we want the diploma to mean something for all students who receive it.

Overview

In this era of significant accountability for schools and districts, many states also focus on high stakes accountability for students (Heubert, 2002; Thurlow & Johnson, 2000). The major federal legislation that supports education in the United States, the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), focuses on system improvement and holding systems responsible for the improved achievement of students. As states face the implications and consequences of system accountability, they have questioned whether they can achieve its goals without imposing student accountability as well—as a way to increase the student motivation necessary for state test performance to reflect what students actually know (O’Neil, Sugrue, Abedi, Baker, & Golan, 1997). In most instances, this student accountability involves adding high school graduation exams to more traditional course requirements.

Exit Exams

More than half of the states have, or will soon have, mandatory exit exams that must be taken and passed as a condition for receiving a standard diploma (Center on Education Policy, 2002, 2003; Johnson & Thurlow, 2003). Tests generally are considered “high stakes” when they are used in making decisions about which students will be promoted or retained in grade, and which will receive high school diplomas (Heubert, 2002; Thurlow & Johnson, 2000).

Exit exams are not a new idea. Several states adopted policies and implemented minimum competency tests in the 1970s and 1980s. The aim was to ensure that students leaving high schools had some minimal set of skills that meant they were ready for the workplace, college, or other post-secondary training. Along with increased global competition in the 1990s came an emphasis on higher levels of student performance. No longer were people interested in the minimal skills reflected in minimum competency tests and the resulting high school diplomas. Increasingly there was evidence that students were leaving schools without adequate skills even though they had received high schools diplomas; this was found to be the case whether the students were in states with minimum competency tests or in states that only had coursework requirements. Evidence of the lack of adequate skills has included complaints from employers about the basic academic skills of high school graduates (Public Agenda, 2002) and the high rate at which high school graduates take remedial courses when they enter college (NCES, 2001).

Initial high failure rates on exit exams in states like Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia triggered attacks on the states’ academic standards and assessments, and produced calls for the tests to be eliminated or deferred. In most cases, the states stayed with the standards that they had set; in some, the passing scores were lowered (Schwartz & Gandal, 2000). Even when states stayed with their original standards, they almost always found that results on graduation exams improved in subsequent years. In Massachusetts, 49% of tenth graders failed either or both of the math and English portions of the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) exam in 2000, compared to 55% who failed at least one of those sections in 1999 (Gehring, 2000). Following an initial jump in the percentage reaching competency in Massachusetts when the tests first counted, the percentage of students passing the graduation tests on the first attempt has shown a steady increase (Wiener, 2004).

The National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) has tracked states’ practices in including students with disabilities in large scale assessment and accountability systems for many years. On occasion, attention has been devoted to those assessments that have high stakes for individual students (Guy, Shin, Lee, & Thurlow, 1999; Langenfeld, Thurlow, & Scott, 1996; Thurlow, Ysseldyke, & Anderson, 1995). Recently NCEO joined forces with the National Center on Secondary Education and Transition (NCSET) to study graduation requirements for students with disabilities (Johnson & Thurlow, 2003). Each time a report is completed, it is again obvious that states’ graduation requirements and the array of exit documents are varied and complex.

Legal Issues

When states grapple with high failure rates or concerns about the performance of certain subgroups of students, legal considerations often emerge. Attention is directed to how students obtain high school diplomas because the high school diploma is considered a property right. A U.S. Supreme Court case, Debra P. v. Turlington (1981), confirmed that a high school diploma is a constitutionally protected property interest, and that the due process provisions of the Fifth and Fourteenth amendments of the U.S. Constitution are applicable to graduation tests. These indicate that students must be given adequate notice of the exams (which, according to Debra P., is four years), and they must have been taught the information included on the tests.

Several subsequent decisions confirmed the Debra P. ruling (for example, Brookhart v. Illinois, 1983). Recent court cases that have addressed exit exams have taken a slightly different twist, focusing in part on the inappropriateness of the tests because of the nature of their accommodation policies as well as the number and type of accommodations that were allowed during the test. Four of these cases are relevant here because of their implications for understanding alternative routes that states have made available for students with and without disabilities to earn a standard diploma.

Rene v. Reed, a 2001 Indiana case, raised two issues about graduation exams: (1) the length of the time period that students knew about the testing requirement—an issue of adequate notice (raised especially for students with disabilities, reflecting a concern that they were unlikely to have had access to the curriculum before the requirement was announced); and (2) the number and type of accommodations allowed for students with disabilities to demonstrate their knowledge and skills. This case was decided in favor of the state, with the judge making the decision on the basis that three years is adequate notice of an upcoming graduation exam, regardless of the student’s prior school experiences. No decision was made on the basis of the accommodation argument.

Advocates for Special Kids (ASK) v. Oregon (1999) argued that students with disabilities did not have an equal and fair chance to pass the state test to earn a Certificate of Initial Mastery because the state’s list of allowable accommodations was too narrow and the research base for the accommodation policies was non-existent. Oregon settled out of court in 2001 agreeing, among other things, to establish an Accommodations Panel that would review research and other evidence each year to determine whether an accommodation produces invalid scores. Oregon also agreed to develop an alternative route for students to earn the Certificate of Initial Mastery when they were unable to demonstrate that they had met the standard through a paper and pencil format.

In Juleus Chapman et al. v. California Department of Education (2001), one concern was that the state had not made sure that students with disabilities had reasonable accommodations during the test. The judge imposed an immediate solution, which was to allow all students with disabilities to receive any accommodations they needed to participate in the exit exam. California now has an advisory panel considering alternatives to the high school exit exam for students with disabilities, with recommendations to be made in 2005.

Alaska also was challenged with a court case by Advocates for Special Kids. Settling out of court in 2004, the state began working on its accommodation policies. During 2004, high school seniors with disabilities were not required to pass the state’s high school exam to graduate (Associated Press, 2004). Provisions for accommodations and other alternatives for subsequent classes are in development.

Alternative Routes

As is evident in the legal cases, there continues to be considerable activity around the high school diploma. Much of this activity lately addresses the concern of what must be done to ensure that students with disabilities have access to the opportunity to earn a diploma and the benefits associated with it. Given the value of the standard diploma, it is important to determine whether those states that have graduation exams provide alternative ways for students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills. And when there is an alternative, it is important to ask whether it requires activities other than completing a paper and pencil test.

The need for an alternative route to a standard diploma comes up most often when talking about students with disabilities. Some disabilities may make it difficult for students to respond via paper and pencil; even if they can respond to this format, it may be difficult to accurately reflect their knowledge and skills. Allowable accommodations may not meet their disability needs. For these students, an alternative route may be needed for them to show their skills. It is likely that similar arguments can be made for students without disabilities—unusual circumstances may arise or other characteristics may create a need to be able to demonstrate knowledge and skills in ways other than with a paper and pencil test.

A survey of special education directors conducted by NCEO (Thompson & Thurlow, 2003) indicated that 24 states had a high stakes graduation assessment, and 3 states were working on one. Seven states reported that passing the assessment was the only way to earn a standard diploma. Directors from the other states gave responses indicating that other routes were available to students.

Directors from eight states reported that students with disabilities could earn a standard diploma without passing the graduation examination. Two states reported that they used a process of juried or performance assessments as an alternative route for students to show knowledge. Three states indicated that they had an appeals process that included students with disabilities, and one state responded that it was developing an appeals process only for students with disabilities. Finally, there were two states that simply indicated they had “other” ways for students to earn a standard diploma.

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore states’ alternative routes after first documenting which states actually do and do not have alternative routes to the standard diploma. Several questions remained unanswered despite the information gathered from the 2003 NCEO survey of special education directors. For example, what exactly are the alternative routes to a standard diploma? Are they indeed waivers from the test, or other ways to determine whether students possess the skills and knowledge equivalent to those measured on the exit exams? Are these options available for all students? Are there some alternatives for students with disabilities and other routes for students without disabilities? What are the specific criteria involved in order for students to access these alternative routes?

It was very important in this study not to confuse the alternative route to the standard diploma that could be used when a state had a graduation exam with the “alternate assessments” that states had developed to meet requirements of the 1997 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Alternate assessments were first defined in IDEA 97 as assessments for students unable to participate in the general assessment. Alternate assessments are included in Title I legislation and in NCLB accountability requirements as a specific state option for system stakes in school, district, and state accountability. It would be easy for an uninformed researcher to confuse an alternative route assessment and an alternate assessment simply because of the similarity of the terms “alternate” and “alternative.” We made it a priority not to confuse these two in our analysis of states’ alternative routes to the standard diploma.

Method

Starting from the NCEO survey data (Thompson & Thurlow, 2003) to identify states that potentially had alternative routes for students to obtain a standard high school diploma, we conducted online searches of state Web sites from October to December 2003. We searched for information about graduation examinations, details about alternative routes for obtaining a standard diploma, and specific criteria required to participate in any alternative route that we identified. We looked in sections of the states’ Web sites related to the topic, such as “Assessment,” “Accountability,” and “Graduation Requirements.” For states that had searchable Web sites we used several of the following key words and phrases: appeals, exit exams, graduation examination, graduation requirements, high stakes tests, high school testing, standard diploma, and waiver.

Once the information was collected from state Web sites, it was summarized in tables and brief descriptive paragraphs. This summary information was mailed in early January 2004 to state assessment directors for verification. In several cases, the state directors delegated the task of verifying the state profiles to other knowledgeable specialists, including education consultants and other state assessment personnel. The states were asked to verify the accuracy of our information. We then followed up by contacting the states by e-mail, and in some cases, by fax. All but four of the states we contacted for verification responded to our request. Changes were made following verification and this verified information is used in this report. The state profiles, which are the basis for tables on alternative routes, are included in Appendix A.

In the process of compiling the report, we analyzed the comparability of each alternative route to the standard route for obtaining a diploma. In early October 2004, we sent our comparability analysis for each state to the state contacts to allow them to review our results and provide other information to us if they disagreed. All but two states responded to this request for verification.

Graduation Exams: The Context for Alternative Routes to Standard Diplomas

Only those states that have graduation exams, or those with other exams that are considered high stakes for students, are likely to have alternative routes for demonstrating mastery of the knowledge and skills measured by those exams. Based on our review of the information in the NCEO report, 2003 State Special Education Outcomes: Marching On (Thompson & Thurlow, 2003), as well as information in the Johnson and Thurlow (2003) report on graduation requirements, A National Study on Graduation Requirements and Diploma Options for Youth with Disabilities, we identified 27 states that had active or soon to be active graduation exams.

The 27 states that we identified are listed in Table 1, along with the year of the first graduating class that is to be held to passing the exam and whether the exit exam is being used by the state to meet NCLB criteria (for example, being used as the high school exam). This table necessarily reflects a snapshot in time.

|

State |

First Graduating Classa |

Exit Exam Used to Meet NCLB Criteria |

Exit Exam Not Used to Meet NCLB Criteria |

|

Alabama |

1985 |

ü |

|

|

Alaska |

2004 |

ü |

|

|

Arizona |

2006 |

ü |

|

|

California |

2006 |

ü |

|

|

Florida |

2003 |

ü |

|

|

Georgia |

1994 |

ü |

|

|

Hawaiib |

2008 |

|

|

|

Idaho |

2005 |

ü |

|

|

Indiana |

2000 |

ü |

|

|

Louisiana |

2003 |

ü |

|

|

Maryland |

2008 |

|

ü |

|

Massachusetts |

2003 |

ü |

|

|

Minnesota |

2000 |

|

ü |

|

Mississippi |

2003 |

ü |

|

|

Nevada |

2003 |

ü |

|

|

New Jersey |

2003 |

ü |

|

|

New Mexico |

1990 |

|

ü |

|

New York |

2003 |

ü |

|

|

North Carolina |

1982 |

|

ü |

|

Ohio |

2007 |

ü |

|

|

Oregonc |

2001 |

|

ü |

|

South Carolinad |

1990 |

ü |

|

|

Tennessee |

2005 |

ü |

|

|

Texas |

2005 |

|

ü |

|

Utah |

2007 |

|

ü |

|

Virginia |

2004 |

ü |

|

|

Washingtone |

2008 |

ü |

|

|

Totals |

|

19 |

7 |

a Information is from Center on Education Policy (2003), with updating as appropriate.

bHawaii does not have clear information about whether its exit exam will be used to meet criteria of NCLB.

cOregon exam is actually for a Certificate of Initial Mastery (CIM). Students receive diplomas regardless of whether they pass the test to earn the CIM.

dSouth Carolina will begin phasing in a new exit exam instead of the current Basic Skills Assessment Program; the new exam is alreadybeing used for NCLB accountability, but will not count as a graduation requirement for high school until 2006.

eWashington was not identified in the Johnson and Thurlow (2003) study as a state planning to have an exit exam. Since the time of that study, it has added an exit exam requirement for a diploma.

We noted as we gathered information from the two sources and checked each state’s information against state Web sites that several states had changed the year in which their exams began to “count” for high stakes. Some states had phased in a new test while phasing out an earlier version of a graduation exam. For example, Texas moved from the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS) to the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS). Students who were enrolled in grade 9 or higher on January 1, 2001, were required to pass the TAAS, regardless of when they graduate. Students who were enrolled in grade 8 or lower at that time, must pass the TAKS. It was at this point, when we realized that there had been considerable change in the landscape, that we decided it would be important to include Oregon’s Certificate of Initial Mastery assessment program in our study even though it was not technically an exam used to determine whether a student would earn a standard diploma.

Although NCLB does not require high stakes exams for individual students, it is possible that states with graduation exams might decide to use those exams for NCLB purposes. In fact, of the 27 states with graduation exams, 19 states indicate that their graduation tests are or will be used for dual purposes (i.e., both as an individual student accountability measure and as a system measure for NCLB).

The fact that some states use the same exams for NCLB system accountability and for graduation exams potentially complicates the issue of whether an alternative route to the standard diploma is available. Not only are the purposes for the NCLB and graduation exams different, but the assessments themselves often are designed differently. Further, only the first administration of an assessment can be used for NCLB accountability, yet graduation exams frequently rely on the possibility of multiple opportunities for retesting.

There is a need to sort out the issues and answer questions specifically related to graduation exams. What happens when students need an alternative way to demonstrate their knowledge and skills? Are there alternative routes to a standard diploma for all students, and if so, what is the nature of these routes? Are there alternative routes for students with disabilities, and if so what is the nature of these routes?

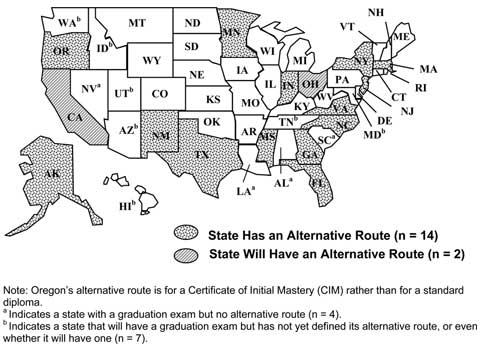

Alternative Route States and Eligibility to Participate

Figure 1 indicates which states have an alternative route to a standard diploma, and which states are in the process of developing a procedure. The states reflected in this figure are those that were identified in the report 2003 State Special Education Outcomes as having alternative routes, adjusted for our initial verification with the states as to the nature of the alternative route and whether it met the criterion of resulting in the student obtaining a standard diploma. In this figure, we include information for states that are in the planning process of implementation for an alternative route only if they had information about their process posted online in the fall of 2003. Thus, of the 27 states that have or will have exit exams (as shown in Table 1), 16 states reported that they have, or will have, some kind of alternative route to a standard diploma (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Alternative Routes to a Standard Diploma (2003-2004)

Four states have active exit exams and no alternative routes to a standard diploma. Those states (with the year of implementation of their high stakes tests) are: Alabama (1985), Louisiana (2003), Nevada (2003), and South Carolina (1990). There are seven states that indicated in response to the NCEO survey that their tests were not active yet, and they did not have plans for an alternative route at that time. Those states are: Arizona (2006), Hawaii (2008), Idaho (2005), Maryland (2008), Tennessee (2005), Utah (2007), and Washington (2008). Because these states did not indicate plans for an alternative route, we did not seek additional information from them.

A summary of the status of the 27 states originally identified as having an active or soon to be in place graduation exam (including Oregon, which has the Certificate of Initial Mastery), is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Status of Alternative Routes for Exit Exams

|

State |

Alternative Route Available |

Alternative Route Not Available |

Test Not Active and No Plans Yet |

|

Alabama |

|

X |

|

|

Alaska |

X |

|

|

|

Arizona |

|

|

X |

|

Californiaa |

X |

|

|

|

Florida |

X |

|

|

|

Georgia |

X |

|

|

|

Hawaii |

|

|

X |

|

Idaho |

|

|

X |

|

Indiana |

X |

|

|

|

Louisiana |

|

X |

|

|

Maryland |

|

|

X |

|

Massachusetts |

X |

|

|

|

Minnesotab |

X |

|

|

|

Mississippi |

X |

|

|

|

Nevada |

|

X |

|

|

New Jersey |

X |

|

|

|

New Mexico |

X |

|

|

|

New York |

X |

|

|

|

North Carolina |

X |

|

|

|

Ohioa |

X |

|

|

|

Oregonc |

X |

|

|

|

South Carolina |

|

X |

|

|

Tennessee |

|

|

X |

|

Texas |

X |

|

|

|

Utah |

|

|

X |

|

Virginia |

X |

|

|

|

Washington |

|

|

X |

|

Totals |

16 |

4 |

7 |

a The state test is not yet active, but information was available on the state Web sites about an alternative route.

b Minnesota indicates that while it does not have an alternative route for general education students at the state level, under limited circumstances, after February of the student’s senior year, a local school district can make accommodations options available as a “last chance” option to pass the test.

cOregon has an exam for a Certificate of Initial Mastery, rather than an exit exam. However, it has an alternative route for this process, so we included this information in our study.

Eligible Student Groups

We looked at the states that have an alternative route to determine whether it was available for all students (which includes students with disabilities), or only for certain subgroups of students, such as students with disabilities. We did this both for those states in which the alternative method was already being implemented, and for those in which it was yet to be implemented because the high stakes assessment was not yet active (but in which an alternative route was planned and designed).

Table 3 indicates the group or groups of students considered eligible for the alternative route to a standard diploma in the 16 states with some type of alternative route available. The table is divided into all students and students with disabilities, with the exact words that are used by the states entered into the table. This table also reveals the groups of students that states cover in general.

Table 3. Students Targeted for Alternative Routes to Standard Diploma

|

State |

Specifically Targeted Students |

|

|

|

All Students |

Students with Disabilities |

|

Alaska |

High school seniors |

Students with IEP or 504 plan |

|

California |

|

Students with IEP or 504 plan |

|

Florida |

12th graders |

12th grade students with IEP |

|

Georgia |

All students |

|

|

Indiana |

All students |

Students with IEP or 504 plan |

|

Massachusetts |

High school seniors |

Students with IEP or 504 plan |

|

Minnesotaa |

All students |

Students with IEP or 504 plan |

|

Mississippi |

All students |

|

|

New Jersey |

All students |

Students with disabilities |

|

New Mexico |

All students |

Students with IEP (504 can be considered) |

|

New York |

High school seniors |

Students with disabilities |

|

North Carolina |

|

Students with IEP |

|

Ohio |

All students |

Students with IEP |

|

Oregon |

All students in grades 9-12 |

|

|

Texas |

|

Students with IEP |

|

Virginia |

All students |

Students with disabilities starting in grade 8 |

Note: Shaded cell indicates that an alternative route is not an option for this group of students in the state. For example, California does not have an alternative route for “all students”; in current plans, an alternative route will be available only to students with disabilities in California for the exit exam that becomes active in 2006.

a Minnesota indicates that while it does not have an alternative route for general education students at the state level, under limited circumstances, after February of the student’s senior year, a local school district can make accommodations options available as a “last chance” option to pass the test.

All but 3 of the 16 states have an alternative route available for all students, and 13 have an option intended for students with disabilities. Three states have created an alternative route available for all students (Georgia, Mississippi, and Oregon), without an additional alternative route specifically for students with disabilities. While Oregon does not technically have a high-stakes graduation exam, it has a test that leads to a Certificate of Initial Mastery (CIM). Three states (California, North Carolina, and Texas) have a process applicable only for students with disabilities with an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or 504 plan. The most common approach is for states to have two alternative routes—one for students with disabilities and another for all students. Ten states (Alaska, Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, and Virginia) take the two route approach (one for all students and one for students with disabilities).

As is evident in Table 3, in some states, both the all students group and the students with disabilities group are defined in a narrower way than simply the larger group. For example, for all students, four states (Alaska, Florida, Massachusetts, and New York) refer to either high school seniors or 12th graders. Oregon refers to all students in grades 9–12. Related to students with disabilities, North Carolina, Ohio, and Texas do not include students on 504 plans, but instead refer to students on IEPs in their descriptions of students available for the alternative route. New Mexico indicates that 504 students might be considered, but technically are not covered by law. Other states (Florida, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia) refer generally to students with disabilities (although Virginia puts a grade limit on the students—“starting in grade 8”). The remaining states (Alaska, California, Indiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota) specifically refer to students with IEPs or 504 plans.

Initiating the Alternative Route to a Standard Diploma

Gaining entrance to the alternative route to a standard diploma does not happen automatically. Typically, there is a procedure that must be initiated by someone. Our review of state Web sites and follow-up state verification indicated considerable variability in whether this information was available or clear. When the information could be found, variability in who could initiate the process was evident.

Table 4 indicates who initiates the alternative route process when it is for all students (which can include students with disabilities) and when it is only for students with disabilities. For 3 of the 13 states in which an alternative route was available to all students, we were unable to find information that indicated who could initiate the alternative route process (Indiana, New York, and Ohio). In the remaining 10 states, the student or a family member only was the initiator in 3 states (Alaska, Georgia, and Oregon), an educator or other school personnel only could initiate in another 5 states (Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico and Virginia), and either family or school personnel could initiate in Minnesota and Mississippi. In Massachusetts, anyone (a parent, guardian, or educator) may request an appeal, but only the superintendent of schools or designee, or the director of an approved private special education school or collaborative may file an appeal (see profile in Appendix A). In Minnesota, after February of a student’s senior year, a student, parent, or the district may request that a general education student take the graduation exam with accommodations, even though the student does not typically use accommodations for instruction.

Table 4 also indicates who initiates the alternative route process when it is for students with disabilities only. For 5 of the 12 states in which an alternative route was available specifically for students with disabilities, we were unable to find information that indicated who could initiate the alternative route process (Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, and Texas). In the remaining 7 states, the IEP or 504 team was specifically cited by 4 states (Alaska, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Virginia), the IEP team or the Superintendent of Schools may initiate the process in Florida, a parent or guardian in California, and the student’s teacher (with principal authorization) in Indiana. In Massachusetts, a parent (or student over 18) may request an appeal and the superintendent must comply.

There may be specific criteria that have to be met as well. For example, students may or may not have to take the exit exam before an alternative route can be used; also, they may or may not have to earn a certain score or participate in remedial activities, or other activities.

Table 4. Initiator of Alternative Route

|

State |

Who Initiates |

|

|

|

For All Students |

For Students with Disabilities |

|

Alaska |

Student, or student’s parent or legal guardian |

IEP or Section 504 team recommends |

|

California |

|

Parent or guardian |

|

Florida |

School guidance counselors |

IEP team |

|

Superintendent of schools |

||

|

Georgia |

Student, parent(s), guardian |

|

|

Indiana |

No information |

Student’s teacher, with principal’s authorization |

|

Massachusetts |

Superintendent of school, or the director of an approved private special education school or collaborative files all appeals |

Superintendent initiates, but for student with disabilities, a parent (or student over 18) may request an appeal and superintendent must comply |

|

Minnesota a |

Student, parent, or the district |

No information |

|

Mississippi |

Student, parent, or district personnel |

|

|

New Jersey |

Local district staff review the Individual Student Reports to see whether the student has demonstrated proficiency on the language arts literacy and/or the mathematics section of the High School Performance Assessment (HSPA). A student must have a partially proficient score in a HSPA content area in order to take the Special Review Assessment (SRA) |

IEP team |

|

New Mexico |

District superintendent |

IEP team |

|

New York |

No information |

No information |

|

North Carolina |

|

No information |

|

Ohio |

No information |

No information |

|

Oregon |

Parent, guardian, student |

|

|

Texas |

|

No information |

|

Virginia |

Local school |

IEP team, 504 committee |

Note: Shaded cell indicates that an alternative route is not an option for this group of students in the state. For example, California does not have an alternative route for “all students”; in current plans, an alternative route will be available only to students with disabilities in California for the exit exam that becomes active in 2006.

a Minnesota indicated that while it does not have an alternative route for general education students at the state level, under limited circumstances, after February of the student’s senior year, a local school district can make accommodations options available as a “last chance” option to pass the test.

Alternative Route Decision Making

Once the request is made to pursue an alternative route for obtaining a standard diploma, someone decides that either (a) the student may continue along the alternative route, or (b) the student has successfully met the requirements of the alternative route. Which type of decision made depends on the nature of the alternative route. Table 5 indicates the decision-making body or approver when the alternative route is for all students (which can include students with disabilities) and when it is only for students with disabilities.

Table 5. Decision-making Body/Approver for

the Alternative Route

|

State |

Decision-maker/Approver |

|

|

For All Students |

For Students with Disabilities |

|

|

Alaska |

Panel of three members appointed by Commissioner |

Department of Education reviews application and if procedures have been followed, the Optional Assessment is approved |

|

California |

|

Local Board of Education |

|

Florida |

State Commissioner |

IEP team |

|

Commissioner of Education |

||

|

Georgia |

State Superintendent of Schools |

|

|

Indiana |

No information |

Case Conference Committee |

|

Massachusetts |

MCAS Performance Appeals Board makes recommendation to the Commissioner |

MCAS Performance Appeals Board makes recommendation to the Commissioner |

|

Minnesota |

District determines |

IEP team |

|

Mississippi |

State Appeals of Substitute Evaluation Committee |

|

|

New Jersey |

The SRA Performance Assessment Tests (PATs) are scored by item-specific rubrics. If two SRA panel members’ scores disagree by more than one point, a third content-certified panel member must score the response. The new PAT score is derived by taking the mean of (for reading or math) or summing (for writing) the two highest contiguous scores. If no two of the three scores are in agreement, the student must complete another PAT |

IEP team |

|

New Mexico |

State Secretary of Education |

IEP team |

|

New York |

No Information |

No Information |

|

North Carolina |

|

No Information |

|

Ohio |

No Information |

No Information |

|

Oregon |

Impartial Panel of Experts |

|

|

Texas |

|

No Information |

|

Virginia |

Local school |

IEP team/504 committee |

Note: Shaded cell indicates that an alternative route is not an option for this group of students in the state. For example, California does not have an alternative route for “all students”; in current plans, an alternative route will be available only to students with disabilities in California for the exit exam that becomes active in 2006.

Procedures used for all students often are different from those used for the

subgroup of students with disabilities. For example, Alaska’s appeals process

for all students uses a panel of three members appointed by the Commissioner of

Education to determine whether to grant the appeal. Mississippi has a State

Appeals of Substitute Evaluation Committee, and New Jersey has a Special Review

Assessment (SRA) Panel that follows item-specific rubrics to make a

determination. Oregon relies on an impartial panel of experts. Virginia leaves

the decision to the local school. School districts make the determination

(including the procedures used) in Minnesota.

Georgia and New Mexico give the power to decide or approve to the State Superintendent, as does Massachusetts with an MCAS Performance Appeals Board making a recommendation. Florida allows the State Commissioner to authorize an alternative test, although the legislature may remove that power. The process of decision-making in four states (Indiana, New York, North Carolina, and Ohio) was unclear on their Web sites, and remained so after verification for those states that confirmed their information.

Table 5 also indicates who makes the decision for the processes involving students with disabilities. In four states (Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Virginia), the IEP team determines whether the alternative method of achieving a diploma is approved. In Florida, the IEP team determines one alternative process and the Commissioner of Education has the responsibility for approving another process. In Indiana, the decision is made by the student’s case conference committee. For Alaska’s Optional Assessment, the Department of Education reviews the application; if the procedures have been followed, the Optional Assessment is approved. In California, the local Board of Education had responsibility for approving or denying alternative routes at the time of our study. The process of decision-making for students with disabilities was unclear on the Web sites of four states (New York, North Carolina, Ohio, and Texas).

Nature of Alternative Routes to a Standard Diploma

There are many variations of alternative routes to achieve a standard diploma. It is difficult to generalize about these processes without understanding the specific criteria and requirements of the various alternative routes. Table 6 includes the name of each state’s alternative route, as well as a brief description of the process. These descriptions are based on the profiles in Appendix A. The information contained in Table 6 was verified by the states (via the profile), and specifically highlights the alternative route available for all students. More detailed information is provided in the State Profiles, as well as on the states’ Web sites (see Appendix B).

Table 6. Nature of the Alternative Route for All Students

|

State |

Alternative Route Process |

|

|

Name of Alternative |

Description of Process or Conditions |

|

|

Alaska |

Waiver from High School Graduation Qualifying Examination (HSGQE) |

A student may receive a waiver if he or she arrives in Alaska with two or fewer semesters remaining in the student’s year of intended graduation. Or, a student has a “rare and unusual circumstance” which consists only of: (1) the death of the student’s parent(s) if the death occurs within the last semester of the student’s year of intended graduation; (2) a serious and sudden illness or physical injury that prevents the student from taking the HSGQE; (3) a disability arising in the student’s high school career and the disability arises too late to develop a meaningful and valid alternative assessment (request for a waiver may only be granted if the waiver is consistent with IEP); or (4) a significant and uncorrectable system error. Or, a student has passed another state’s competency examination. |

|

California |

No alternative route for “all students” |

|

|

Florida |

Alternative Test |

Other standardized tests, such as SAT and ACT college entrance exams can count as comparable to passing scores on the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT). |

|

Georgia |

Waiver/Variance |

Request for waiver/variance must include a statement of what will be accomplished in lieu of requirements, reason for the request, and permission for the student’s records to be reviewed. |

|

Indiana |

CORE 40 (Waiver from Graduation Qualifying Exam proficiency standard) |

Student successfully completes academically challenging courses in English, mathematics, science, and social studies, and earns at least a C in all required and elective courses. [Not verified by state] |

|

Indiana (continued) |

Appeal Test Results |

Student meets State Board criteria (takes exam in each subject area; completes all remediation opportunities; minimum attendance of 95%; minimum C average in courses required for graduation), plus must obtain written recommendation from teacher in subject area(s) where did not get passing score on Graduation Qualifying Exam, and principal must agree with recommendation, with documentation provided to ensure student has attained the academic standard based on other tests or classroom work. Student must satisfy all other state and local graduation requirements. [Not verified by state] |

|

Massachusetts |

MCAS Performance Appeals |

Eligibility: Student must have 95% attendance during previous and current school years: must have taken the MCAS test(s) three times; must have scored 216 or 218 at least once (no minimum score for a student with a disability); and must have participated in MCAS tutoring or other academic support. Performance requirements: grade point average must meet or exceed GPA of a “cohort” of six or more students who passed the MCAS. Methods of Appeal: Cohort Analysis or Student Portfolio, when a cohort does not exist, for all students. |

|

Minnesota |

No official state-approved alternative route |

Minnesota does not have an alternative route for general education students at the state level, but under limited circumstances, after February of the student’s senior year, a local school district can make accommodations options available as a “last chance” option to pass the test. |

|

Mississippi |

Appeals/substitute evaluation |

Student is eligible when a student, parent, or district personnel has reason to believe a student has mastered the subject area curriculum, but was unable for two separate administrations to demonstrate mastery on the statewide Subject Area Testing Program; if the appeal is approved, the student is allowed to take a substitute evaluation, which is then judged to determine whether it demonstrates mastery of the curriculum. |

|

New Jersey |

Special Review Assessment (SRA) |

The SRA is an individually, locally administered, state-developed assessment. Each SRA question (known as a Performance Assessment Task or PAT) is aligned to the High School Proficiency Assessment content. The student must obtain a partially proficient score on the HSPA to qualify for the SRA process. The student must also participate in a school-designed SRA instructional program for that content area. Students may take an SRA PAT once. If a student is not successful on a specified PAT, additional PATs may be administered until the student successfully completes the required number of PATs. |

|

New Mexico |

Waiver |

Waiver may be requested for any student, but there must be documentation of attainment of competencies through other standardized assessment measures. |

|

New York |

No information |

Students may take other tests in place of Regents Tests—Advanced Placement test, SAT II, International Baccalaureate test. [Not verified by state] |

|

North Carolina |

No alternative route for “all students” |

|

|

Ohio |

Appeal |

Student must pass 4 of the 5 tests, 97% attendance rate, 2.5 GPA, completed curriculum requirements, participate in intervention programs with 97% attendance, and have letters recommending graduation from high school principal and each high school teacher in subject area not yet passed. [Not verified by state] |

|

Oregon |

Juried State Assessment |

Three types of evidence fall within the Juried State Assessment: (1) A Collection of Evidence to the ODE for review; (2) A Modification Request to determine if a modification used during the administration of a state test should be considered an accommodation for the student for each particular test; or (3) A Proficiency-Based Admissions Standards System (PASS) transcript as evidence of having met CIM standards by meeting the corresponding PASS Standards in a content area. [Not verified by state] |

|

Texas |

No alternative route for “all students” |

|

|

Virginia |

Substitute Tests |

Substitute tests may be taken for verified credit, which then can be counted for Standards of Learning (SOL) end of course exams. The state provides a list of SOL Substitute Tests for Verified Credit. It includes tests like AP exams, ACT, SATII, etc. |

Table 7 provides similar information about the alternative routes to a standard

diploma for students with disabilities. In general, the options for students

with disabilities are different from those for all students. References to the

IEP are among the most striking difference. Still, even with this commonality in

the processes for students with disabilities, there is a range of options that

states are using for this group of students.

Table 8 provides a summary of whether each of the options first requires the student to take the general assessment, and by inference, to fail the exit exam, before having access to the alternative route to the standard diploma. In the table, the options for all students are positioned beside those available to students with disabilities only. It is noteworthy that there is little symmetry within states that have alternative routes both for all students and for students with disabilities only in terms of whether the student must first take the general assessment. In fact, in the 10 states that have alternative routes to standard diplomas for all students and for students with disabilities, less than half had the same pattern (Florida, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia). A total of 6 states of 13 require all students to first fail the exit exam, while 5 states of 13 require students with disabilities to first fail the exit exam.

Table 7. Nature of the Alternative Route for Students with Disabilities

|

State |

Alternative Route Process |

|

|

Name of Alternative |

Description of Process or Conditions |

|

|

Alaska |

Optional Assessment (OA) |

To participate in an OA, a student must have attempted to pass all sections of the High School Graduation Qualifying Examination (HSGQE) with or without accommodations, be recommended by the IEP or 504 team, have approval in writing to take the OA, have a copy of the IEP or 504 plan, only take the OA for the content areas for which the student received a below or not-proficient score. OAs are changes to the administration of the HSGQE, not to the content or the format. Administration changes include use of four function calculator, asking test proctor for clarification about test questions, allowing signer to interpret test questions for a deaf student, allowing use of a spell checker on word processor, allowing use of dictionary or thesaurus. |

|

California |

Waiver |

Student with IEP or Section 504 plan who takes the California High School Exit Exam (CAHSEE) with a modification determined to fundamentally alter what the test measures and receives the equivalent of a passing score (350 or higher) may request waiver of the requirement to successfully pass that section of CAHSEE. |

|

Florida |

Florida’s Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT) Waiver |

Legislation provides for waiver of the Grade 10 FCAT for students with disabilities whose abilities cannot be accurately measured by the FCAT. |

|

Special Exemption |

Exemption under extraordinary circumstances that would cause the test to reflect student’s impaired sensory, manual, or speaking skills rather than the student’s achievement. Note: Students who are granted an exemption must meet all other criteria for graduation with a standard diploma. |

|

|

Georgia |

No alternative route for students with disabilities only |

|

|

Indiana |

Waiver |

Student’s case conference committee recommends that requirements be waived and demonstrates that student has attained the academic standard. Student must meet specific criteria, including retaking exam in subject areas which he or she did not pass, as often as required by IEP, completes remediation, maintains school attendance of 95%, maintains C average or equivalent, satisfies all other state and local graduation requirements. [Not verified by state] |

|

Massachusetts |

Alternate Assessment |

“Competency portfolio” may be submitted in lieu of taking MCAS tests for students with disabilities who have been designated for alternate assessment by their IEP or 504 team. |

|

Minnesota |

(No Name) |

Test may be modified or scores may be lowered. |

|

Mississippi |

No alternative route for students with disabilities only |

|

|

New Jersey |

IEP Exemption |

Students must take the High School Proficiency Assessment (HSPA) at least once in each content area before qualifying for exemption. |

|

New Mexico |

Graduation Pathways (Standard, Career Readiness, and Ability) |

For students who do not achieve a passing score on the graduation exam, three pathways are available. For the standard pathway, the IEP team selects courses and electives based on the student’s post-school goals, interests, and needs; the student must pass the exit exam. For the career readiness path, the students must take the exam, but the score that must be achieved is determined by the IEP team. The ability pathway is for students with significant cognitive or physical disabilities; these students must take the exit exam or the state alternate exam and meet IEP team determined criteria. |

|

New York |

Regents Competency Test |

A safety net provision allows students with disabilities who fail the Regents Exam to take and pass the Regents Competency Test to earn a local diploma. This option is available until 2010. [Not verified by state] |

|

North Carolina |

Occupational course of study |

IEP team determines the criteria. |

|

Ohio |

(No Name) |

Students whose IEP excuses them from the consequence of having to pass the OGT may be awarded a diploma. [Not verified by state] |

|

Oregon |

No alternative route for students with disabilities only [Not verified by state] |

|

|

Texas |

(No Name) |

Student receiving special education services who successfully completes the requirements of his or her IEP shall receive a high school diploma. |

|

Virginia |

Virginia Substitute Evaluation Program (VSEP) |

The VSEP consists of a student’s Course Work Compilation (CWC), a selection of student work that demonstrates to the review panel that the student has demonstrated proficiency in the Standards of Learning for a specific course/content area. The student must have a current IEP or 504 plan, be enrolled in a course that has an SOL test or be pursuing a modified standard diploma, and the impact of the student’s disability demonstrates that the student will not be able to access the SOL assessments even with standard or non-standard testing accommodations. |

Table 8. Summary of Whether Alternative

Route Requires Student to First Take (and Fail) the General Assessment

|

State |

All Students |

Students with Disabilities |

||

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Alaska |

|

X |

X |

|

|

California |

|

X |

|

|

|

Florida |

|

X |

|

Xa |

|

Georgia |

|

X |

|

|

|

Indiana |

Xb |

Xb |

X |

|

|

Massachusetts |

X |

|

|

Xc |

|

Minnesota |

X |

|

|

X |

|

Mississippi |

X |

|

|

|

|

New Jersey |

X |

|

X |

|

|

New Mexico |

|

X |

X |

|

|

New York |

|

X |

|

X |

|

North Carolina |

|

|

X |

|

|

Ohio |

X |

|

|

X |

|

Oregon |

|

X |

|

|

|

Texas |

|

|

X |

|

|

Virginia |

|

X |

|

X |

|

Total |

6 |

8 |

5 |

8 |

a

Florida provides two

alternative routes. See Table 7.

b

Indiana provides two

alternative routes. See Table 6.

c Students with significant disabilities whose IEP

or 504 team designate them for participation in the alternate assessment also

have the option of moving to the “all students” alternative route (the

performance appeal), but only after attempting the alternate “competency

portfolio” at least twice.

Table 9 synthesizes the specific nature of alternative routes to a standard

diploma for all students in terms of whether the route involves (a) taking a

different test, (b) completing a specific curriculum, (c) using a different

method of demonstrating proficiency, or (d) obtaining a waiver from

requirements. Indiana is the only state that had two alternative routes

available to all students. As a result, it has two checks in this table, and the

totals in the columns for different test, different curriculum, different

method, and waiver will add together to give a number (total = 14) that is

larger than the number of states that have alternative routes for all students

(n = 13).

Five states (Florida, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and Virginia) allow students to use other tests to demonstrate competency. A Florida statute initially permitted this option only for the 2003 school year, but the alternative was extended for another year and will be studied for future years. In New Jersey, high school students who do not pass the High School Proficiency Assessments (HSPA) may take the SRA after participating in a school-designed instructional program for the content area in question. Local school district staff review the Individual Student Reports to see whether the student has demonstrated proficiency on the language arts and/or the mathematics section of the HSPA. A student must have a partially proficient score in an HSPA content area in order to qualify to take the SRA. New York allows students to take an Advanced Placement test, SAT II, or International Baccalaureate test in lieu of the Regents Exam. In Virginia, students who do not pass the Standards of Learning (SOL) end-of-course exams may retake an alternative form of the test immediately, or may take a substitute test.

Table 9. Alternative Routes for All Students

|

State |

Different Test |

Different Curriculum |

Different Method |

Waiver |

|

Alaska |

|

|

|

üm |

|

Florida |

üa |

|

|

|

|

Georgia |

|

|

|

ü n |

|

Indiana |

|

ü f |

üg |

|

|

Massachusetts |

|

|

üh |

|

|

Minnesota |

|

|

üi |

|

|

Mississippi |

|

|

üj |

|

|

New Jersey |

ü b |

|

|

|

|

New Mexico |

üc |

|

|

|

|

New York |

üd |

|

|

|

|

Ohio |

|

|

ük |

|

|

Oregon |

|

|

ül |

|

|

Virginia |

üe |

|

|

|

|

Total |

5 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

Note: The total obtained from adding across the columns in this

table (total = 14) is greater than the number of states (n = 13) because Indiana

has two alternative routes available for all students.

a

Standardized tests, including SAT, ACT,

College Placement Test, PSAT, PLAN, and tests used for entry into the military

(available by statute for 2003 only, but extended for another year).

b A locally administered, state-developed test

made up of performance assessment tasks that are administered in a familiar

setting, with additional required instruction.

c

In very limited circumstances, statute

permits students to demonstrate competency through other standardized measures

(considered a “waiver”).

d

Advanced Placement test, SAT II,

International Baccalaureate test.

e

State provides list of substitute tests

including AP exams, ACT, SAT II, etc.

f

CORE 40 curriculum-students must

successfully complete all courses earning at least a “C."

g

Recommendation based on other tests or

classroom work.

h Performance appeal in which grades are compared

with those of a cohort; if sufficient number in cohort are not available, then a

portfolio is developed.

i

State does not have an approved alternative

route for all students, but a school district may permit a student without an

IEP or 504 plan, after February in his or her senior year, to take the

graduation exam with accommodations after repeated unsuccessful attempts.

j

Substitute evaluation with supporting

evidence.

k

May pass one fewer test but must meet

additional criteria.

l

Juried assessment (Classroom based work

samples before expert panel).

m

Waiver under very specific, limited

conditions such as death of parent, serious illness, etc.

n

Waiver must include what will be

accomplished in lieu of requirements and permission to review student’s records.

New Mexico allows the use of an alternative test only in limited instances with extenuating circumstances. For example, if a student transferred from another state and had not taken “New Mexico History,” the superintendent could request a waiver for that portion of the test, and submit evidence of competencies demonstrated through other standardized assessment measures. However, this option is used very sparingly and approved on a case-by-case basis.

Only one state had an alternative route to the standard diploma that was based only on completing a specific curriculum. Indiana has an alternative known as the Core 40 curriculum. The student’s principal must certify within a month of the student’s graduation date that the student has successfully completed all of the Core 40 requirements with at least a “C” grade. A student who does not pass the Graduation Qualifying Exam, and who does not meet the requirements of Core 40 may graduate by successfully appealing the test results under specific criteria adopted by the Board of Education. The student may be eligible to appeal if he or she has taken the graduation exam, completed all remediation opportunities provided by the school, maintained a minimum attendance rate of 95%, maintained a “C” average in all courses required for graduation, and has obtained a written recommendation from the student’s teacher in each subject area in which the student has not achieved a passing score. The principal must verify this information and documentation must be provided to ensure that the student has achieved the academic standard in the subject area based on tests other than the graduation exam or classroom work.

Six states have other approaches of demonstrating competency (Indiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Ohio, and Oregon). In Indiana, students who have not passed the test may appeal their results and earn a diploma by meeting all other graduation requirements and obtaining written recommendations from teachers in subject areas where a passing score was not obtained, and an agreement from the principal, as well as completing other requirements. Massachusetts has a performance appeal that involves the student comparing his or her grades to that of a cohort of students who have passed the MCAS. If a cohort of sufficient size is not available for comparison, then the student submits a portfolio.

Minnesota does not have an alternative route for general education students at the state level, but under limited circumstances, after February of the student’s senior year, a local school district can make accommodations options available as a ‘last chance’ option to pass the test, even if the student does not typically use accommodations for instruction. Mississippi allows all students who appear to have “mastered the subject area curriculum, but who were unable for two separate administrations to demonstrate mastery on the Subject Area Test,” to have the opportunity for an appeal. If a student does not pass the test, the student, the parent, or district personnel may appeal for a substitute evaluation. If the results of the substitute evaluation determine that the student has mastered the curriculum, a passing score will be substituted for a failing score on the Subject Area Test, and the Mississippi Department of Education will absorb the cost associated with the substitute evaluation.

In Ohio, the student must meet an array of criteria as an alternative to passing the high school graduation exam that consists of 5 tests. The student must pass 4 of the 5 tests, have a 97% attendance rate, have a 2.5 GPA, complete all the curriculum requirements, participate in intervention programs with a 97% attendance rate, and have letters recommending graduation from the high school principal and each high school teacher in subject areas not yet passed.

In Oregon, the State Board established an alternative pathway to the Certificate of Initial Mastery (CIM) for students who are unable to demonstrate mastery on one or more statewide assessments required for the CIM. Students in the alternative are evaluated on a collection of classroom-based work samples through a process known as a juried assessment.

Two states have waiver provisions. In Alaska, it is possible for certain students to earn a diploma without passing the High School Graduation Qualifying Examination (HSGQE). Students in the “waiver” group include those who met the criteria of “rare and unusual circumstances,” such as the death of a student’s parent(s) if in the last semester of the student’s year of graduation, a sudden or serious illness or injury, or having passed a similar test in another state. Georgia makes reference to waiver provisions for students who do not pass the examinations, although the criteria are unclear on the Web site. There is a list of information that must be submitted to indicate what will be accomplished through a waiver or variance, the reason for the request, and permission for a record review.

Table 10 summarizes the specific nature of alternative routes to a standard diploma for students with disabilities in terms of whether the route involves (a) taking a different test, (b) completing a specific curriculum, (c) using a different method of demonstrating proficiency, or (d) obtaining a waiver from requirements. One state (Florida) has two alternative routes for students with disabilities, and thus two checks have been entered for these two alternative routes. Both fall within the same category even though they have different names and are carried out in slightly different ways. Because of the two checks, the totals in the columns for different test, different curriculum, different method of demonstrating competency, and waiver will add together to give a number (total = 14) that is larger than the number of states that have alternative routes for students with disabilities (n = 13). Considering the table overall, and compared to Table 9, it is evident that the overall distribution of states across the types of alternative routes is quite different for students with disabilities compared to all students.

Table 10. Alternative Routes for Students with Disabilities

|

State |

Different Test |

Different Curriculum |

Different Method of Demonstrating Competency |

Waiver |

|

Alaska |

üa |

|

|

|

|

California |

|

|

|

üi |

|

Florida |

|

|

|

üüj |

|

Indiana |

|

|

ü f |

|

|

Massachusetts |

|

|

ü g |

|

|

Minnesota |

ü b |

|

|

|

|

New Jersey |

|

|

|

ü k |

|

New Mexico |

|

ü d |

|

|

|

New York |

ü c |

|

|

|

|

North Carolina |

|

ü e |

|

|

|

Ohio |

|

|

|

ü l |

|

Texas |

|

|

|

ü m |

|

Virginia |

|

|

ü h |

|

|

Total |

3 |

2 |

3 |

6 |

Note: The total obtained from adding across the columns in this table (total = 14) is greater than the number of states (n = 13) because Florida has two alternative routes available for students with disabilities.

a Optional Assessments are changes to the administration of the high school test, not to the content or format, i.e., using spell-checker, allowing student to ask questions of proctor, etc.

b Tests may be modified or scores may be lowered.

c The Regents Competency Exam is a safety net option for students to earn a local diploma.

d Career Readiness pathway allows for student to pass with a score pre-determined by the IEP team; Ability Pathway is for students with severe cognitive disabilities and/or physical disabilities, or students with severe mental health challenges who must take either the exit exam or the alternate assessment and meet IEP pre-determined level of competency.

e Occupational course of study with criteria determined by IEP team.

f As recommended by teachers, tests other than Graduation Qualifying Exam or classroom work.

g Portfolio assessment.

h Portfolio assessment.

i Waiver for a portion of the test may be requested for students who take the exit exam with modifications that change what the test measures, and who meet a minimum score.

j Exemption available for students with impaired sensory, manual, or speaking skills, if they meet all other criteria for graduation; waiver available for those students whose abilities cannot be accurately measured by the exit exam.

k Exemption after taking (and failing) high school exit exam at least once.

l IEP exemption.

m IEP determined criteria for diploma.

Three states (Alaska, Minnesota, and New York) provide options that rely on different tests. For students with disabilities in Alaska, there is an Optional Assessment (OA) available to obtain a regular high school diploma. These students must have been unsuccessful when they took the high school graduation examination, and also must meet several other criteria in order to take the OA as an alternative to getting a high school diploma (see Alaska State Profile in Appendix A). In Minnesota, the graduation test may be modified or passing scores may be lowered for students with disabilities. Exemptions and individual passing scores are based on the student’s IEP or 504 plan and the recommendation of the IEP team. New York has a “safety net” for students with disabilities who fail the Regents graduation exam. This provision allows students to take and pass the Regents Competency Test to earn a local diploma. This alternative method has been extended through the 2009–2010 school year.

Two states (New Mexico and North Carolina) provide options that rely on the use of a different curriculum to demonstrate proficiency and meet the requirements of a standard diploma. New Mexico offers alternative pathways—standard pathway, career readiness pathway, and ability pathway—as a means to achieve a regular diploma or certificate of achievement. If the IEP team recommends a pathway other than the standard one, the team must provide documentation for selecting the alternative pathway. All students must still take the New Mexico High School Competency Exam (NMHSCE), except for those with the most severe cognitive disabilities who would take the alternate assessment. However, the IEP team can adjust the level of passing required for individual students with disabilities based on their IEP or 504 plan. The career readiness pathway focuses on the student’s interests, career preferences, and needs in determining selection of appropriate classes. The ability pathway is an individual program based on meeting or surpassing IEP goals and objectives. North Carolina also offers an occupational course of study for students with an IEP. However, no exit exam is required for students who are following the occupational course of study.

Three states (Indiana, Massachusetts, and Virginia) have different methods of demonstrating competency. In Indiana, the case conference committee of a student with a disability or 504 plan who does not pass the Graduation Qualifying Exam may determine that the student is eligible to graduate if he or she meets several very specific criteria, including a 95% attendance rate, maintaining at least a “C” average, and otherwise satisfying all state and local graduation requirements. In Massachusetts, a “competency portfolio” may be submitted in lieu of taking MCAS tests for students with disabilities who have been designated for alternate assessment by their IEP or 504 team. In Virginia, students must accrue verified credits. A verified credit is granted if students pass the class and the corresponding Standards of Learning (SOL) test. Students with disabilities who cannot be accommodated on the regular SOL tests can take a portfolio assessment called the Virginia Substitute Evaluation Program (VSEP).

Five states (California, Florida, New Jersey, Ohio, and Texas) have a waiver provision for students with disabilities. Florida actually has two different types of waivers, and thus was given two checks in Table 10. The ENNOBLES Act of Florida is legislation that provides for the waiver of the Grade 10 Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT) for students with disabilities whose abilities cannot be measured accurately by the FCAT. The student’s IEP team may request a waiver of the FCAT requirement if that student meets all requirements set forth in the ENNOBLES Act. In addition to this waiver option, Florida also has a Special Exemption for “extraordinary circumstances” that allows the student to be exempt from “any or all sections of the test required for high school graduation with a standard diploma.” Students who are granted an exemption must meet all other criteria for graduation with a standard diploma.

The waiver options in other states are more like the first waiver option in Florida. California’s high stakes testing is not scheduled to begin until 2006. The plans indicated on the Web site provide the opportunity for a waiver only for students with disabilities. Students with an IEP or 504 plan who take the California test with modifications that fundamentally alter the test and what it purports to measure, and who receive a score of 350 or higher, may request a waiver for the portion of the California High School Exit Examination (CAHSEE). They would still qualify for a regular diploma. California is currently conducting a study to determine specifically how this process will be implemented.

In Ohio and Texas, students whose IEP excuses them from having to pass the exit exams may be awarded a diploma if they successfully complete the requirements of their IEP.

Comparability of Alternative Routes and Standard Routes