Five Formative Assessment Strategies to Improve Distance Learning Outcomes for Students with DisabilitiesDistance learning can be very challenging for teachers, as well as for students with disabilities and their families. Teachers are sometimes having to use unfamiliar technologies while at the same time figuring out how to effectively instruct students who may not be very engaged in an online environment. Similarly, students with disabilities and their families may be frustrated by the technology and the demands created by distance learning. Formative assessment is a process that may help improve the distance learning experience. Formative assessment is important for all kinds of learning. It may be especially important for distance learning, which can easily turn into a “list of things to do” in the minds of students. Compliance with directions—doing a list of assignments—leads to completion, but it is not guaranteed to lead to learning. And even if it does, students who merely complete work may not be clear on what, exactly, it is they have learned by doing it. Formative assessment focuses students on learning and evidence of learning. It has the potential to be a powerful antidote to the “check-box” approach some students may bring to online learning.

Formative assessment can be used to improve learning for all students, but is particularly important for students with disabilities. The purpose of this Brief is to describe the use of formative assessment with students with disabilities during distance learning. Formative assessment can occur every time teachers interact with students with disabilities or their work, either in person or virtually. It is the process of gathering, interpreting, and using information about student learning while the learning is happening. Effective formative assessment happens when teachers, students with disabilities, and parents (when possible) work together on what the students are learning, monitor how the learning is going, and adjust then readjust as the days and situations change. Formative assessment is important for students with disabilities because its elements correspond with the process of self-regulated learning. It is especially important for students trying to learn content they find difficult because it builds confidence and helps conceptualize what they are learning and what complete understanding looks like. Students who struggle with the content of a lesson may not easily reason backwards from lesson content to learning intentions. As such, the student’s involvement in formative assessment will help counteract these tendencies. Student involvement could look like suggestions for innovations (via emails, survey, phone calls, breakout rooms), individual reflection, or evaluation of learning.

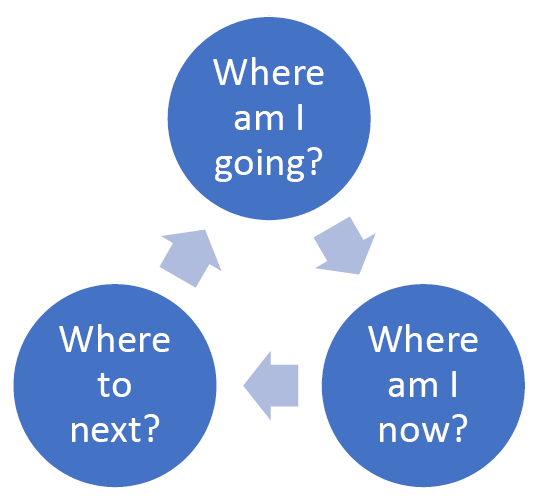

The Formative Learning CycleThink of formative assessment as providing information that positions students in a formative learning cycle identified by three questions: Where am I going? Where am I now? Where to next? (See Figure 1.) The formative learning cycle is based on students with disabilities having at least some idea about what they are trying to learn and what it will look like when they do (Where am I going?). In the formative learning cycle, feedback becomes information students need and want (Where am I now? Where to next?). Feedback sometimes even helps students clarify the goal in their minds (Where am I going?). This is especially important in a distance learning environment where students sometimes struggle to orient to what they are learning. On the other hand, if students are not intentionally trying to learn something, there is no formative learning cycle and feedback is just another set of teacher directions to follow. Figure 1: Formative Learning Cycle

Formative Assessment StrategiesMany formative assessment strategies can be used to fuel the formative learning cycle and help make sure students with disabilities know what they are trying to learn and use evidence from their learning to continue to improve. Most of them can be easily adapted for distance learning. The five suggestions presented here represent a good place to start. They were selected because they:

The five suggestions are recommendations for first steps in formative assessment for students with disabilities, in distance learning. These recommendations are not an exhaustive list of formative assessment strategies. Educators who want additional ideas should explore the suggestions for further reading. Strategy 1. Establish and communicate clear learning targets.A learning target is a statement of what students will be trying to learn in a lesson. It should be written from a student’s point of view and directly coupled with both a student performance (something the students will do, make, say, or write in order to learn and produce evidence of their learning) and a set of qualities that students can look for in their work to gauge their learning. The set of guidelines are sometimes called “success criteria” or “look-fors,” and no learning target is complete without them. The performance part is what online learning platforms do best. However, a performance assigned without a learning target and success criteria can easily become just busywork, no matter how rich the task is. In students’ minds, a performance task may be just something to “get done” if there are no learning intentions. Most online classroom platforms are set up to emphasize the things students will do rather than what they will learn. In most distance learning platforms, students log into a course or class. Within each class, there are further subdivisions. Some are relatively simple with only a few tabs, such as for ongoing conversation or discussion, classwork or assignments, and a list of people or classmates. Students using some online learning platforms may have many more choices, including announcements, modules, discussion boards, assignments, badges, conferences, small group workspaces within the class, and so on. The first job of formative assessment in online learning is to move the focus back to learning. For every lesson, students should know from the outset: What am I trying to learn? Why is it important? Why now—what is so important that I must learn it now even though I cannot be in school? For most lessons, the “why” includes helping students understand not only what they are going to learn in this lesson, but how that is a step in a learning trajectory that leads to some larger learning goal. In assignment-based learning platforms, students may experience each “assignment” in roughly the same way they experience a “lesson” in face-to-face instruction, as one step on the way to learning something bigger like a unit learning goal. So for each assignment, think of introducing it by answering the question, from a student’s point of view, “What am I going to learn by doing this?” For example, a learning target might be, We are learning to use vivid verbs to make our sentence more interesting or I can use vivid verbs to make my sentence more interesting. The exact format of the learning target statement makes little difference; use wording that will make the most sense to your students. The important criterion is that students will understand the statement as what they are trying to learn. If a learning target seems to carry over several assignments, students should know what this assignment adds to the learning they have already accomplished. For example, Yesterday we practiced using vivid verbs in simple sentences. Today we’re going to get more practice by using vivid verbs in short descriptive paragraphs to make the whole description more intense. Explain why that learning target is important, how what students learned in yesterday’s lesson prepared them for today’s lesson, and how today’s lesson will lead to tomorrow and beyond. Here are some suggestions for communicating learning targets in online lessons or assignments. A one-shot announcement of the learning target at the beginning of the lesson will not suffice to keep the learning target top-of-mind as students do their assignment. Use several of these strategies together, as appropriate in each lesson, to help students understand Where am I going? and aim for learning, not just completion, as they work.

Strategy 2. Establish and communicate clear criteria for success.Learning target statements are not complete without criteria that students and teachers can look for in student work. For example, if a student is trying to use vivid verbs in a sentence, how will the child know they are making progress toward this goal? The criteria are the means by which they—and you, their teacher—will know. The criteria for this learning target will also help students form their concept of what a “vivid verb” really is and why they might want to learn to use them in their writing. In terms of this example, the criteria might be one or more of the following: My verb is the main word in the action part of the sentence. My verb makes me think of something I can see, hear, smell, taste, or touch. My verb makes my sentence interesting to read. These criteria give the student specific things to strive and look for in their work. They also embody the learning target in a way that helps clarify for students what exactly it means to use vivid verbs in writing. Notice that the success criteria are about qualities one would notice in student work, not scores or grades. The criteria do not, for example, say “I can write five sentences with vivid verbs” or “I can substitute vivid verbs in 80% of the sentences on this worksheet” or anything like that. The concept of qualities “showing” in the work is what makes this formative assessment, which is about monitoring work for the evidence it provides about a student’s formative learning cycle. Success criteria support both students’ self-assessment during learning and teachers’ feedback. If success criteria are clear, parents and caregivers can use them as they help their children, and the criteria will focus their help on learning as opposed to just “getting things right.” In contrast to formative strategies like student self-assessment and teacher feedback, the concept of grading or scoring is a summative assessment concept, which is about measuring where students arrived after instruction. Eventually, of course, these same criteria can be used to evaluate work submitted for grading, but not at this point in the cycle on work performed during, and as part of, learning. Students will try to produce what is asked for, so it is important to take a lot of care in crafting success criteria and to ask for qualities that really indicate things worth learning. Many teachers find identifying clear criteria much more difficult than writing a learning target statement, but despite the challenge, this step should not be skipped. In some ways the success criteria are more important to the formative learning cycle than the learning target. Here are some suggestions for establishing and communicating clear success criteria.

Strategy 3. Build in opportunities for students to self-assess or ask questions, based on criteria.Clear, appropriate, and effective success criteria are the key to most other formative assessment strategies, especially student-centered ones. Here are some suggestions for ways to incorporate self-assessment and student questioning into online lessons.

Strategy 4. Give brief, clear, actionable feedback based on the criteria

Feedback is more important than ever for students working alone or with parents or caregivers, or even when working in small groups within an online learning platform. Whether mandated by a district or not, make sure to give feedback of some sort on everything students do. Feedback is effective if it helps students move along in the formative learning cycle toward a learning goal. It does not have to be long, but it needs to be precise. “Nice job” does not help promote the formative learning cycle. The words chosen are important, and one of the nice things about online feedback is that it can be read and edited before sending. The precision—and thus the helpfulness—of feedback comes from using the same success criteria that the students have been using. Success criteria focus teacher feedback on the student learning shown in their work. Without them, feedback turns into a teacher’s free-association response to student work, which is not likely to help the student move along the formative learning cycle. Or it may turn into copyediting or supplying correct answers, neither of which helps students learn much. Here are some suggestions for giving brief, clear, actionable feedback based on criteria in online learning.

Strategy 5. Give students opportunities to revise assignments or re-do similar assignments.Feedback cannot be effective if students are not able to use it. Sometimes teachers think students will mentally file away their comments and remember them when they are doing similar work again. That rarely happens for any student. For feedback to be effective in moving students along the formative learning cycle, students must have an opportunity to use the feedback. Those opportunities should be planned as part of instruction. Online learning may have an advantage over face-to-face learning in this regard because much of the work is done asynchronously. This makes the amount and timing of students’ individual work less dependent on what other classmates are doing. Here are some suggestions for helping all students use feedback in online learning.

ConclusionThe five strategies suggested here do not cover all of formative assessment, but they are absolutely essential to the formative learning cycle for students with disabilities, just as they are for all students. For this reason, these five strategies are the most appropriate first steps for teachers beginning to incorporate formative assessment into online learning. Because these strategies privilege student understanding of their learning, they can become an antidote to the “getting done” mentality some students may bring to online learning. For these two main reasons—supporting student understanding of their own learning and combating a “just get it done” approach to online learning—we recommend prioritizing these five strategies as formative assessment is incorporated into online teaching for students with disabilities. Teach your students how to focus on what they are trying to learn. Notice how they use these methods and respond to them. Once these strategies are used successfully in every online lesson, additional formative assessment strategies can be explored, such as student goal-setting, students tracking their own progress, and peer assessment. The Further Reading section provides some resources that give more explanation and examples of the strategies included here and information about additional formative assessment strategies as well. Ultimately, the most important reason to use formative assessment is that it helps students learn. Students with disabilities, like all students, should know what it is they are learning, and they should know how they are doing, even as they learn. Further ReadingBrookhart S., & Lazarus, S.S. (2017). Formative assessment for students with disabilities. Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/Formative_Assessment_for_Students_with_Disabilities.pdf Chappuis, J. (2015). Seven strategies of assessment for learning (2nd ed.). Pearson. Moss, C. M., & Brookhart, S. M. (2019). Advancing formative assessment in every classroom (2nd ed.). ASCD. Wiliam, D. (2018). Embedded formative assessment (2nd ed.). Solution Tree.

NCEO Brief #20, May 2020The author of this Brief was Susan Brookhart. NCEO Director, Sheryl Lazarus; NCEO Assistant Director, Kristin Liu. All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Brookhart, S. (2020, May). Five formative assessment strategies to improve distance learning outcomes for students with disabilities (NCEO Brief #20). National Center on Educational Outcomes. NCEO is supported through a Cooperative Agreement (#H326G160001) with the Research to Practice Division, Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education. The Center is affiliated with the Institute on Community Integration at the College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota. The contents of this report were developed under the Cooperative Agreement from the U.S. Department of Education, but does not necessarily represent the policy or opinions of the U.S. Department of Education or Offices within it. Readers should not assume endorsement by the federal government. Project Officer: David Egnor NCEO works in collaboration with Applied Engineering Management (AEM), Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE), and WestEd.

This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. Direct requests to: National Center on Educational Outcomes |