Prepared by Lynn Walz, Debra Albus, Sandra Thompson, and Martha Thurlow

This document has been archived by NCEO because some of the information it contains is out of date.

Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Walz, L., Albus, D., Thompson, S., & Thurlow, M. (2000). Effect of a multiple day test accommodation on the performance of special education students (Minnesota Report No. 34). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/MnReport34.html

A recent survey of

state testing policies in the United States (Thurlow, House, Boys, Scott, & Ysseldyke,

2000) found that 26 states allowed multiple test sessions (offering breaks) for statewide

testing of students with disabilities. Three additional states allowed multiple sessions

in some testing situations, but not all. The survey also found that 18 states allowed a

multiple day accommodation for large scale tests. Four additional states allowed multiple

day testing under certain conditions. These conditions usually referenced certain state

tests or test components, with timing specifications or additional security measures.

Three states prohibited the accommodation in all testing situations.

This study was designed to determine the effect of allowing

students to take a reading test over multiple days versus taking the same reading test

within one day. A multiple days/sessions test accommodation, categorized most often as a

scheduling accommodation, is similar in some ways to the accommodation of extended time.

For example, the rationale of potential benefits from testing across multiple days may be

compared to similar benefits from extended time in that students with disabilities may

perform better when testing time is not restricted to one regular testing period on one

day. Some overlap may even occur between extended time and multiple session categories if

students are allowed to take breaks within a testing session or between sections of a test

that add additional time to the overall testing period. Also, although taking a test

across multiple days does not necessitate using extended time, accommodations are usually

packaged together in ways that combine extended time with other accommodations.

No research studies have been done on multiple day testing

accommodations (Tindal & Fuchs, 1999), yet teachers are familiar with this

accommodation. A study of teachers’ knowledge of accommodations in large scale

testing (Hollenbeck, Tindal, & Almond, 1998) showed that 45% of the teachers surveyed

had correct knowledge about the multiple day/sessions accommodations, and that 18% of the

teachers allowed this testing accommodation with students receiving special education

services.

Part of the rationale for the potential benefits of multiple day

testing come from findings in studies of extended time. These studies have examined the

effect of extended time for special education students of various ages, though more

studies have been done with post-secondary students. In studies with college age students,

extra time was found to be beneficial to the performance of students with learning

disabilities on a range of skills (Elliott, Kratochwill, McKevitt, Schulte, Marquart,

& Mroch, 1999; Ofiesh, 1997; Tachibana, 1986; Weaver, 1993). In at least one study,

the longer testing times also produced some fatigue that may have adversely affected

student performance (Tachibana, 1986). Other studies with post-secondary students found no

benefit of extended time (Marquart, 2000) or greater benefit for students without learning

disabilities than students with learning disabilities, as on a written Graduate Record

Examination (GRE) (Chiu & Pearson, 1999; Halla, 1988).

Fewer studies of

extended time have focused on elementary and secondary students. One study looking at

fifth graders’ Iowa Test of Basic Skills scores in different timed conditions showed

no effect when the amount of time was reduced (Munger & Loyd, 1991). In a study of

third graders on a mathematics calculations test (Montani, 1995), students with learning

difficulties in math (but not reading) performed less well in a timed condition compared

to the control group; students with difficulties in math and reading performed worse in

both timed and untimed conditions.

These studies of

extended time have shown that although offering extended time may benefit some students,

it may also fatigue students if the testing session becomes too long with the added time.

In another study, extended time was associated with better emotional reactions of students

to the testing condition and better self evaluation of their performance (Marquart, 2000).

Actual performance benefit was still dependent on the individual student’s skills and

cognitive abilities required for specific tests and question types (Burns, 1998; Montani,

1995).

The advantage of

offering multiple day testing with extended time would arguably include the benefits of

allowing extra time with the potential of allaying fatigue by having more than one day to

complete longer tests. Further, if a multiple day/session accommodation was offered alone

without extended time, there is still potential benefit of taking a break between testing

segments, provided that test segments do not awkwardly break up the momentum built into a

test through practice items, item difficulty, or unbalanced difficulty in testing sessions

leading to potential student frustration (Burns, 1998). Other possible criticisms of

testing across multiple days are that a student’s test readiness might vary from the

first day of testing to subsequent days (Burns, 1998) or that the validity of a test is

less secure across multiple days. Clearly, studies focusing on multiple day testing are

needed before reaching a conclusion about these potential advantages or disadvantages.

This study was

conducted to examine the effects of allowing students to take a reading test over multiple

days versus taking a reading test within one day. Two research questions were the focus of

the study:

1. Is the

performance of students receiving special education services enhanced when taking a

reading test administered across three days versus all in one day?

2. Do students

receiving special education services benefit more than regular education students from the

multiple day test accommodation?

Method

Participants

The study was

conducted in four middle schools in Minnesota. Two of these were rural East Central

Minnesota schools, and two were urban schools. A total of 113 students participated in the

study, 64 students in 7th grade and 49 students in 8th grade. There were 47 females and 66

males. None of the students in this study had previously taken the Minnesota Basic

Standards Tests on which the test passages used in this study were based. There were 112

students who had complete test data to be included in the analysis (48 students receiving

services for academic or behavioral needs and 64 non-special education students). Students

were selected on the basis of whether they did or did not receive special education

services. Later, a check with the district database revealed that seven students in the

urban general education group were identified as non-English language background (NELB)

status. The potential for unintended interactions between possible differences in language

ability and performance is explored in the Discussion section. Table 1 shows the student

population in the study by rural/urban district, grade, gender, and general special

education services.

Table 1 Study Population

|

Rural |

Urban |

||||||

|

7th

Grade |

8th

Grade |

7th

Grade |

8th

Grade |

||||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Study Design

Table 2 shows the

design of the study by the order in which conditions were presented to students (Multiple

Day first vs. One Day first), and whether the student was in General Education or

receiving Special Education services.

Test Instruments

All test passages

for the One Day and Multiple Day administrations were based on reading passages reworked

from earlier versions of the Minnesota Basic Standards Test. The test passage length of

all the reading articles ranged from 900 to 1,040 words. The questions for each passage

addressed both literal and inferential comprehension. The five passages available for use

in this study were developed and tested to be of similar difficulty. The passages were

previously used in one or both of two other studies, one on bilingual translation

accommodations (Anderson, Liu, Swierzbin, Thurlow, & Bielinski, 2000), and another on

dictionary accommodations for LEP students (Albus, Bielinski, Thurlow, Liu, 2001).

The test passages

used for the Multiple Day administration included three passages that all students took.

Students were administered one passage per day across three days, with 10 questions per

passage. The test passages for the One Day administration were composed of two other

passages of similar difficulty, plus one of the passages from the Multiple Day

administration. For the One Day condition, students answered 30 questions (10 questions

for each of the three passages) all on the same day.

Table

2. Study Design

Group |

First Condition |

Second Condition |

Special |

One Day |

Multiple Day |

Multiple Day (Accommodated) |

One Day (Unaccommodated) |

|

General |

One Day |

Multiple Day |

Multiple Day (Accommodated) |

One Day (Unaccommodated) |

Oral Reading Instrument

To assess the

students’ reading rate, all students also were asked to read aloud a short passage

each day for one minute. The passages were newspaper-style stories given in article form,

similar to the passages used for the test. The two passages that were most closely matched

for difficulty and that were read by the majority of students were used to estimate the

reading fluency rates. Students were then categorized into three groups based on reading

rate: below 50 words correct per minute, 50 to 99 words correct per minute, and 100 and

above words correct per minute. These groupings of students were used to analyze whether

there was an interaction between reading rate and test performance in either or both

conditions. The hypothesis was that slower readers might benefit from taking only one

passage per day while faster readers might not.

Students were tested

in school classrooms in groups of 15 to 25 students. All students in the General Education

and Special Education groups were administered reading tests across both conditions:

Multiple Day and One Day, so that testing occurred across four consecutive days. The two

groups in the study were both split in half. One half of each group received the

unaccommodated (One Day) condition followed by the accommodated (Multiple Day) condition.

The other half received them in reverse order, accommodated then unaccommodated condition.

Due to scheduling arrangements with schools, the order of testing conditions was in one

direction for rural students and in the reverse for urban students. All students in the

study participated in both testing conditions so that their performance on each could be

compared.

One minute oral

reading samples were collected each day for every student. The samples were collected by

proctors who met individually with students after the reading test had begun. Because of

scheduling concerns, students were pulled out individually from the testing session, then

returned after their minute of oral reading. Reading rate scores were calculated from

reading data recorded on student data sheets. Students were allowed as much time as needed

to finish the reading passages for each day.

In one classroom

administration for students in the special education group, a brief disturbance occurred

at the beginning of the testing time. Approximately 10 minutes elapsed before students

were again settled so that testing instructions could begin. The possible effect of this

temporary disruption on students’ test performance is unknown, but students were

allowed as much time as needed, as in other test administrations.

Schools varied in

their policies for returning students to classes. After students completed the test

passages for each day they were either released back to their regular classes or released

to another room to do other activities before group dismissal to regular classes. A

make-up day was provided in two schools where students had been absent during the testing

time.

Accuracy Checks on Data

Oral reading rates

were entered onto an Excel spreadsheet. Every student’s reading rate score and score

transfer was checked for accuracy by a second proctor. The inter-rater agreement for

reading rate, calculated from student data sheets, was approximately 80%. Data errors were

corrected by the second proctor.

Results

Test Performance

The main hypothesis

for this study was that testing students with disabilities for shorter periods over three

days would result in higher test performance than when the students had to complete an

entire test in one sitting. The second part of this hypothesis is that general education

students would perform equally under the two conditions. Table 3 shows the mean number

correct under both conditions.

Group

|

|

One Day |

|

Special

Education |

Mean |

10.28 |

10.98 |

4.25 |

4.98 |

||

N |

47 |

47 |

|

|

Mean |

14.05 |

16.14 |

Standard

Deviation |

7.32 |

5.01 |

|

N |

63 |

63 |

Note: The N

includes only students who had scores for both conditions.

For special

education students, the mean number correct was similar for the Multiple Day and the One

Day conditions, with the Multiple Day slightly less than the One Day. On average, general

education students performed less well when taking the test across multiple days than when

taking it all on one day. A repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant effect for

test condition (Multiple Day vs. One Day) with Multiple Day performance significantly

lower than One Day performance, F(1, 108) = 9.21, p = .003. Neither the group effect

(Special Education vs. General Education) nor the interaction between group and test

condition was significant.

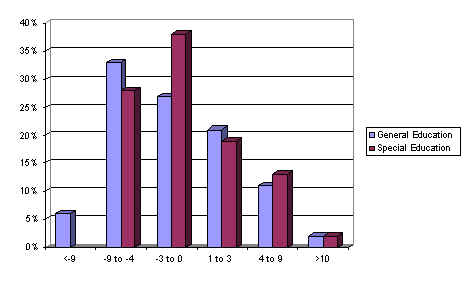

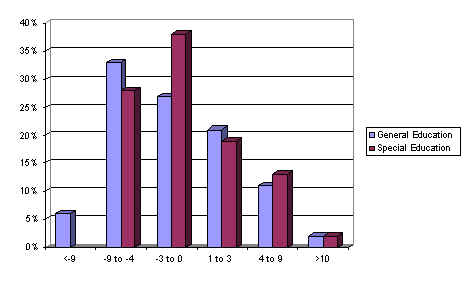

Closer inspection of

individual results revealed several unexpected findings. For example, one student answered

only 4 of 30 items correct in the Multiple Day, but answered 22 of 30 items correct in the

One Day condition. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the differences between Multiple Day

and One Day performance. For the example just given, the difference would be 4-22, or

–18. As indicated in the figure, there were fewer outliers in the direction favoring

Multiple Day (e.g. >10) than in the direction favoring One Day (e.g., < -9). Even

when we removed scores that were two standard deviations above or below the mean for each

group, the results remained the same. In other words, Multiple Day performance was

significantly lower than One Day performance, F(1,101)=11.78, p=.001.

Oral Reading Rate

Since reading rate

may be an important variable for determining who might benefit from testing across

multiple days, we examined its relationship to performance under Multiple Day and One Day

conditions. Table 4 shows the mean number of words read correctly in one minute for both

groups. This table includes only those students who had a valid reading rate (all but two

cases) and whose gain/loss was not extreme (see above). Additionally, one case was removed

because the reading rate was extreme (243 wpm.) On average, the General Education students

read 108 words per minute, compared to only 58 words per minute for the Special Education

students.

Table 4. Mean Number of Words Read Correctly for Both

Groups

|

|

Standard |

N |

Special Education |

57.72 |

26.82 |

46 |

General

Education |

107.66 |

28.45 |

56 |

Table 5 shows the

mean number of words read correctly in one minute (WPM) for the Special Education and

General Education students grouped into three reading rate levels.

Reading rate

groups by |

||||

<50 WPM |

50-100 WPM |

>100 WPM |

||

Special

Education |

Mean |

31.1 |

102.8 |

|

General

Education |

Mean |

46.00 |

86.4 |

124.9 |

Finally, Table 6 shows the mean difference score (Multiple Day minus One Day) by reading rate and by group. Table 6 shows the test score difference between the two conditions for special education status crossed with reading rate. The results are based on the data with outliers removed. A repeated measures ANOVA was run using reading rate groups as the fixed factor in order to ascertain whether slow readers differentially benefited from the accommodation than faster readers. The interaction was not significant F(2,99)=1.14,p=.32.

Groups

|

<50 |

50-100 WPM |

>100 WPM |

Total |

|

Mean |

-.53

3.55 19 |

-1.13

3.52

24 |

-2.33

6.43

3 |

-.96 3.66 46 |

|

General Education |

Mean |

3.00

1.41

2 |

-2.48

3.96

21 |

-1.09

4.24 33 |

-1.46

4.17 56 |

Total |

Mean |

-.19

3.54 21 |

-1.76

3.75

45 |

-1.19

4.35 36 |

-1.24

3.94 102 |

The results of this

study indicated that a multiple-day test accommodation did not enhance the test scores of

students with learning disabilities. However, it did significantly affect the test

performance of general education students, with lower performance taking the test across

multiple days. In fact, the results showed slightly higher performance for both groups

under the One Day unaccommodated condition. Possible reasons for these results, and

factors that may have limited these findings, are discussed.

Lack of “Fatigue Effect”

Although this study

did not specifically track the test times of individual students across all testing

sessions, the test sessions for Special Education and General Education groups across the

Multiple Day condition were estimated to vary between 60 minutes and 100 minutes; the

total time for test sessions in the One Day session varied between 34 minutes and 150

minutes. This may imply that although students were given unlimited time, they did not

take longer in one condition than in the other.

The need to examine

a multiple day accommodation grew out of concerns about possible fatigue effects created

by a Basic Standards Test that required students to complete five reading passages, each

with ten test questions. For this study, we were able only to use items that had been

prepared for research. Furthermore, there was a need to keep the overall testing session

of limited duration. In general, schools are hesitant to participate in a study in which

students are pulled out of their classrooms for extended periods of time. Using a longer

test in a multiple day accommodation study could possibly produce different results

because the “fatigue effect” would be more likely to occur.

If students are

allowed to use unlimited time for the tests, whether in the accommodated or unaccommodated

condition, there is the potential that they experience psychological benefits of an

untimed test administration (Marquart, 2000). This could have influenced the results in

this study, where the decision not to time the tests was in keeping with actual testing

practices in the administration of the Basic Standards Tests. In a situation where

students are under specific time constraints, for a comparable single day vs. multiple day

testing condition, the results may differ. In this situation, a multiple day accommodation

might have a different influence on performance, particularly with other test types of

longer duration or other time constraints.

Number of Students in Lowest Reading Fluency Level

A potentially

limiting factor in this study is that few students (N=19) from the special education group

were in the lowest oral reading category of 50 wpm or less. Therefore, the number of

students potentially more likely to benefit from a multiple day reading test

administration was a small subset of the students with disabilities. Further studies with

larger numbers of students whose reading levels are low would be beneficial.

Non-English Language Background Students

Students for this

study were selected on the basis of whether they received special education services.

During the study, we found that seven students in the urban general education group had a

home language other than English. For these students, the study procedures may not have

worked as intended. For example, the oral reading measure may not be as valid for this

population. While a study with second grade bilingual Hispanic students (Baker & Good,

1994) showed the measure to be reliable, another study looking at possible racial, ethnic,

and gender bias in students grades 2-5 (Kranzler & Miller, 1999) found racial and

ethnic bias at the fourth and fifth grade levels and some bias for gender in the fifth

grade level. The authors of this study concluded that the meaning of oral reading scores

may differ across race, ethnicity, or gender at different grade levels. It is important

for future studies to consider how or to what extent language background issues, ethnicity

and gender issues, or students’ grade level may influence the meaning of oral reading

scores of students in a study population.

Limitations

Like testing

sessions in schools, there is always the possibility that unplanned events (e.g., fire

alarm) will occur. At the beginning of a testing session at one site in this study there

was a temporary disruption lasting for approximately 10 minutes. This affected only the

Special Education group. While testing resumed following the disruption with no further

problems, the extent to which the disruption may have influenced the students’ test

performance for that testing day is unknown.

Studies of

accommodation effects are plagued by the need to separate the effect of the accommodation.

In reality, most students receiving accommodations often use multiple accommodations

rather than one in isolation (Elliott, Thurlow, Bielinski, DeVito & Hedlund, 1998).

Although students in this study may be considered to have had “extended time” in

addition to the multiple day accommodation, even though extended time is not an official

accommodation in this study, there are other accommodations (i.e., marking answers

directly into a test booklet rather than filling in bubbles on an answer sheet or small

group administration) that may have otherwise been normally used by some students but were

not provided in this study. In attempts to isolate the potential benefits of a multiple

day accommodation, it is possible that real world validity was compromised. These types of

issues in accommodations research for students with disabilities are problematic, but can

and should be addressed.

Conclusion

Research on the

effects of test accommodations is critical if we are to justify the use of accommodations

for students who need them to best show what they know in testing situations. Although

there are acknowledged weaknesses in this study, it is useful in furthering the discussion

of multiple day accommodation research and accommodations research in general. Some main

points to consider for further studies include:

•

More multiple day testing accommodation studies would be

beneficial with different types and lengths of tests as well as including a wider range in

ages of students.

•

In striving for authenticity, it is important to consider how

groups or pairings of accommodations, which may normally be used by students, are dealt

with when attempting to study a particular accommodation. In this study, the multiple days

accommodation may not have only been influenced by the length of the test, but also by the

fact that it was untimed or that an accommodation that a student may usually have used was

not provided.

•

Increased knowledge and awareness of language-related factors

among students, or even other non-language related factors, in regular and special

education populations is needed to insure that the measures used are reliable for the

students they are intended to measure.

•

Closer collaboration between schools and researchers is needed

to best develop and

im-plement research designs.

References

Albus, D.,

Bielinski, J., Thurlow, M., & Liu, K. (2001).

The effect of a simplified English language dictionary on a reading test (LEP Projects

Report 1). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational

Outcomes.

Anderson, M., Liu,

K., Swierzbin, B., Thurlow, M., & Bielinski, J. (2000). Bilingual accommodations for limited English

proficient students on statewide reading tests: Phase 2. (Minnesota Report 31).

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Baker, S. K., &

Good, R. (1994). Curriculum-based measurement

reading with bilingual Hispanic students: A validation study with second-grade students.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Council for Exceptional Children / National

Training Program for Gifted Education (Denver, CO, April 6-10, 1994.)

Burns, E. (1998).

Test accommodations for students with disabilities. Springfield,

IL: Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, LTD.

Chiu, C. W. T.,

& Pearson, P. David (1999). Synthesizing the

effects of test accommodations for special education and limited English proficiency

students. Paper presented at the National Conference on Large Scale Assessment.

Elliot, J.,

Bielinski, J., Thurlow, M. DeVito, P., & Hedlund, E. (1999). Accommodations and the performance of all students on

Rhode Island’s performance assessment (Rhode Island Report 1). Minneapolis, MN:

University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Elliott, S. N.,

Kratochwill, T. R., McKevitt, B., Schultze, A., Marquart, A., & Mroch, A. (1999). Experimental analysis of the effects of testing

accommodations on the scores of students with and without disabilities: Midproject

results. Unpublished manuscript, University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Gajria, M., Salend,

S. J., & Hemrick, M. A. (1994). Teacher acceptability of testing modifications for

mainstreamed students. Learning Disabilities

Research and Practice, 9 (4), 236-243.

Halla, J. W. (1988).

A psychological study of psychometric differences in Graduate Record Examinations General

Test scores between learning disabled and non-learning disabled adults (Doctoral

dissertation, Texas Tech University, 1988). Dissertation

Abstracts International, 49, 0230.

Hollenbeck, K.,

Tindal, G., & Almond, P. (1998). Teacher’s knowledge of accommodations as a

validity issue in high-stakes testing. The Journal

of Special Education, 32 (3), 175-183.

Kranzler, J. H.,

& Miller, M.D. (1999). An examination of racial

/ethnic and gender bias on curriculum-based measurement of reading. Unpublished

manuscript. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 435 087).

Lambert, D., Dodd,

J. M., Christensen, L., & Fishbaugh, M. S. E. (1996). Rural secondary teachers’

willingness to provide accommodations for students with learning disabilities. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 15 (2), 36-42.

Munger, G. F., &

Loyd, B. H. (1991). Effect of speededness on test performance of handicapped and

non-handicapped examinees. Journal of Educational

Research, 85 (1), 53-57.

Marquart, A. M.

(2000). The use of extended time as an accommodation

on a standardized mathematics test: An investigation of effects on scores and perceived

consequences for students of various skill levels. Paper presented at the annual

meeting of the Council of Chief State School Officers, Snowbird, UT.

Montani, T. O.

(1995). Calculation skills of third-grade children with mathematics and reading

difficulties (learning disabilities) (Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers, The State University

of New Jersey, 1995). Dissertation Abstracts

International, 56/03, 891.

Ofiesh, N. S.

(1997). Using processing speed tests to predict the benefit of extended test time for

university students with learning disabilities (Doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania

State University, 1997). Dissertation Abstracts

International, 58, 0176.

Perlman, C.L.,

Borger, J., Collins, C. B., Elenbogen, J. C., & Wood, J. (1996). The effect of extended time limits on learning

disabled students’ scores on standardized reading tests. Paper presented at the

annual meeting of the National Council on Measurement in Education, New York, NY.

Shinn, M. R. (Ed.)

(1989). Curriculum-based measurement: Assessing

special children. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Tachibana, K. K.

(1986). Standardized testing modifications for learning disabled college students in

Florida (modality) (Doctoral dissertation, University of Miami, 1986). Dissertation Abstracts International, 47, 0125.

Thurlow, M., House,

A., Boys, C., Scott, D., & Ysseldyke, J. (2000).

State participation and accommodation policies for students with disabilities: 1999 update

(Synthesis Report 33). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on

Educational Outcomes.

Tindal, G., &

Fuchs, L. (1999). A Summary of research on test

changes: An empirical basis for defining accommodations. Lexington, KY: University of

Kentucky. Mid-South Regional Resource Center of the Interdisciplinary Human Development

Institute.

Weaver, S. M.

(1993). The validity of the use of extended and

untimed testing for postsecondary students with learning disabilities (extended testing). Unpublished

doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto.