Prepared by Michael Anderson, Kristin Liu, Bonnie Swierzbin, Martha Thurlow, and John Bielinski

This document has been archived by NCEO because some of the information it contains is out of date.

Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Anderson, M., Liu, K., Swierzbin, B., Thurlow, M., & Bielinski, J. (2000). Bilingual accommodations for limited English proficient students on statewide reading tests: Phase 2 (Minnesota Report No. 31). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/MnReport31.html

Not long after the

standards-based educational reform movement began in the early 1990s, researchers and

policymakers began urging educators to include as many students with limited English

proficiency as possible in large-scale assessments. Inclusion of students in the testing

programs holds states and school districts accountable for educating these children and

provides data on which to base evaluations of programs and services (Rivera &

Stansfield, 1998; Stansfield, 1996). Recently, however, the national discussion has

focused on ways to make the tests appropriate for English language learners who

participate, so that assessments give a reliable picture of what students know and can do.

Changes to the setting or administration of the test are commonly called “accommodations.”

Extended time, explanation of directions, use of a familiar examiner, and testing in a

small group or individual setting are some of those commonly allowed (Aguirre-Munoz &

Baker 1997; Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO], 1999; Rivera & Stansfield,

1998; Rivera, Stansfield, Scialdone, & Sharkey, 2000; Thurlow, Liu, Erickson, Spicuzza

& El Sawaf, 1996). Changes to the test itself, often referred to as “modifications,”

are more controversial and less frequently allowed. Some states permit content areas to be

translated into students’ native languages or alternate forms of the test to be

developed in those languages (Aguirre-Munoz & Baker, 1997; CCSSO, 1999; Rivera et al.,

2000), but such decisions may be based largely on educators’ beliefs about what will

help students, not on actual data.

To date, there is

little research to document the effects of accommodations or modifications, including

translated tests, on the scores of students with limited English proficiency (Butler &

Stevens, 1997). The research that has been done often limits students to just using a

native language version of the assessment (e.g., Abedi, Lord, & Hofstetter, 1998,

discuss the translation policy for the National Assessment of Educational Progress). In

practice, however, students with low-level English skills may feel pressure from peers and

parents to choose the English language version of a test even when a separate native

language version is available and might help them (Liu, Anderson, Swierzbin & Thurlow,

1999; Stansfield, 1997). In general, an

argument can be made for the use of dual language test booklets that provide items in

English and the native language on facing pages so that students do not have to make a

public choice between the majority language and minority language version. A few pieces of

literature do, in fact, mention the use of dual language test booklets. The National

Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education (NCBE) (1997) recommends a dual language format as a

possible strategy for LEP students who cannot take the standard form of the test. The

Council of Chief State School Officer’s 1999 survey of assessment programs indicates

that five states allow dual language versions of a large-scale assessment. Stansfield

(1997) surveyed educators who work in multilingual school settings outside of the United

States and found that those who had used a dual language test format liked it.

Tests of English

language reading ability are usually presented only in English since the standard being

assessed is reading comprehension of a passage written in the primary language of

instruction. However, the specifications for the Minnesota Basic Standards Test (BST) of

reading, a test that students must pass to receive a diploma, state that the passage must

be in English, but no mention is made of the language used for the questions and answer

choices (Minnesota Department of Children, Families and Learning [CFL], 2000). It should

be stressed, however, that currently bilingual accommodations on the Basic Standards

reading test are not allowed. The Basic

Standards Test of reading is made up of four reading passages, often taken from newspaper

articles, that are 600-900 words in length and are written at about an 8th grade level. Each passage has 10 multiple choice questions

accompanying it. Often a fifth passage is completed by students as a field test of new

items. Students must finish all sections of the test within one day but the CFL places no

time limit on the test other than this (CFL, 2000).

Anecdotal

information from schools suggests that many LEP students take an entire school day to

finish the 5 passages and the task of decoding that amount of English in one sitting is

physically and mentally draining for students. Past research of the Minnesota Assessment

Project has shown that LEP students perform at lower levels on the BST reading test than

the BST math test, which may be due in part to the amount of English that students have to

decode and the amount of unfamiliar vocabulary found in both the reading passages and the

questions and answer choices (Liu et al., 1999a; Liu & Thurlow, 1999b; Liu, Thurlow,

Thompson & Albus, 1999c). Often, the complexity of the concepts and language found in

standardized reading test questions and answers poses a significant barrier for LEP

students (Garcia, 1991). Some of the vocabulary gives crucial information about how to

complete the item and may not be found in the reading passage.

This study examined

a reading test form with the passage in English but all other test information, including

test directions and test questions and answers, written in two languages side-by-side and

presented aurally in the native language on a cassette tape. Phase 1 of the study examined

the processes of creating and field testing the dual language test booklet (Liu et al.,

1999a) and included interviews with students about their use of the bilingual

accommodations. It was found that while use of the accommodations varied from student to

student, most of the students did not use the taped version of the test questions and used

the test questions written in Spanish as a reference when they encountered a difficult

vocabulary item in English. This report (Phase 2) examines the feasibility of providing

such an accommodation and the impact of the accommodation on student test scores. Both

reports are unique in that they also examine student opinions about the usefulness and

desirability of the accommodation. Translated tests are expensive to produce and large

districts may have 60 or more languages spoken in the LEP student population. Information

about students’ perspectives on the use of translations is critical in order for

policymakers to determine whether the expense of producing translations is warranted.

This study was

designed to answer the following research questions:

1. Does

giving students reading test questions in both English and Spanish (both aurally and in

writing) enable them to better demonstrate their understanding of the text?

2. How

do students use these accommodations?

3. Will

students use the accommodations if they are made available?

Procedure

Instrument

The instrument used

for this study was a reading test developed by personnel at the Minnesota Department of

Children, Families and Learning to approximate a version of the Minnesota Basic Standards

reading test. The test consisted of four reading passages that were all taken from

newspaper feature articles. Each passage was followed by ten multiple-choice questions.

The reading passages and questions were originally developed for use in the Basic

Standards reading test, but were not used. The testing team (an ESL specialist, test

specialists, and a bilingual translator) modified the passages and the questions to be as

close as possible to items that would actually be used in the statewide test. The test

questions, or items, were then translated into Spanish and formatted in a side-by-side

fashion with the original English language form of the questions (see Appendix A). The

reading passages were not translated, but presented only in English.

The Minnesota Basics

Standards reading test must contain literal and inferential comprehension questions. The

test used in this study contained 29 literal and 11 inferential questions. The Minnesota

Basic Standards reading tests contain at least 12 inferential questions. This might

indicate that our test was slightly easier than an actual Minnesota Basic Standards

reading test. On the other hand, the test used in this study was slightly longer than the

Minnesota Basic Standards reading test, containing just over 3800 words, while the Basic

Standards reading test is limited to no more than 3400 words. In this respect our test

might have been more challenging. Overall, the test used in this study was made to

resemble, as closely as possible, the Minnesota Basic Standards Test reading test.

With the translation

guidelines of the International Test Commission (Van de Vijver & Hambleton, 1996) in

mind, the testing team used the following process to translate the test questions. First,

the test was reviewed for cultural bias. A bilingual translator then translated the test

questions into Spanish. The questions were translated back into English (a “back

translation”) by another bilingual translator and compared to the original English

questions. Relatively few differences were found. A member of the original testing team

and the original translator reconciled changes to the Spanish version of the questions.

The test was piloted with nine students who were interviewed about each test question, the

format of the test, and their use of the accommodations (see Phase 1: Liu, Anderson,

Swierzbin, & Thurlow, 1999). After this first phase of the study, taking the

back-translation and student input into account, a few relatively minor changes were made

to some of the questions in the Spanish version.

While the reading

passages were presented only in English, the

test questions were presented side-by-side in English and Spanish to the experimental

group. The participants also were able to listen to the test directions and test questions

read aloud in Spanish on an audiocassette. Each participant had an individual tape player

with headphones with which to listen to the audiotape if desired. Each student controlled

his or her tape player and was able to listen or re-listen to the items on the tape as

needed. The study included both written and tape-recorded translations since that is the

format in which the accommodation package is offered for the state’s translated math

test and presumably would be offered by the state if this accommodation were allowed for

the reading test. The student taking the test could decide what version(s) of the

translation to use, if any.

Approximately two

hours were scheduled for each testing session. The few students who did not finish during

this time were allowed to stay to finish the test. Thus, although the test was untimed,

the students were aware that there was the expectation that they finish the test more or

less within the time allotted.

Test Validity

Since this test had

never been used before, several measures were used to gauge the validity of the

instrument. A Kuder-Richardson Formula 20 reliability coefficient for the test across all

of the experimental and control groups was high (0.92). The same coefficient for the

general education control group only was 0.85, for the accommodated LEP group it was 0.85,

and for the unaccommodated group it was 0.79. These data indicate that the test used in

this study had the same or higher internal consistency as the actual Minnesota Basic

Standards reading test (0.85) for most of the test groups.

The weighted average

score for the actual Basic Standards reading test for the entire general education

population at the sites used in this study was 32.5. This compares to an average score of

30.1 for the general education sample of students in the present study. These numbers

indicate that the test used in this study was slightly more difficult than the actual

Basic Standards reading test for a general education population.

Participants

The participants in

Phase 2 were 206 eighth grade students from five schools in Minnesota. The schools were in

both the Twin Cities and in greater Minnesota. The study was conducted over a two-year

period (school years 1998-99 and 1999-2000) with two consecutive eighth grade classes. The

participants in the study were separated into three test groups: an accommodated LEP

group, an unaccommodated LEP group, and a control group of general education students.

Each school was asked to invite all eighth grade students receiving LEP services whose

first language was Spanish to participate in the study. LEP students who agreed to

participate were assigned to the accommodated or unaccommodated group. About 80% of the

LEP students were randomly assigned to these groups, at a couple of schools, however, more

students were assigned to one or the other group so that the overall numbers of students

in each group would be similar. A group of native English-speaking general education

students at each site was also invited to participate in the study. The accommodated LEP

group took the version of the test with questions in the bilingual format, while the

unaccommodated LEP group and the general education group took the test with questions

presented only in written English. The accommodated LEP group was tested separately from

the other two groups.

The LEP students completed a short survey about their language background before the test. The survey was adapted from a language characteristic survey by the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES, 1992). Those students in the accommodated LEP group were also asked to answer several questions about their use of the accommodations after each of the four reading passages as well as one question about their overall use of the accommodations on an exit card at the end of the test. The students were also asked how long they had lived in the U.S. Although time in the U.S. for the LEP students ranged from less than one to more than nine years, 48.5% of the students answering this question reported being in the U.S. nine years or more. Family economic indicators for all of the students were collected from a state database after the test (see Table 1).

Table

1: Summary of Participants by Test Group

Group |

N |

Male |

Female |

Percent Eligible for Free/Reduced Lunch |

Accommodated LEP |

53 |

28 |

25 |

81.2% |

Unaccommodated LEP |

52 |

25 |

27 |

94.2% |

General Education |

101 |

44 |

57 |

22.7% |

Total |

206 |

97 |

109 |

58.3% |

Research Question 1: Does giving students reading test questions

in both English and Spanish (both aurally and in writing) enable them to better

demonstrate their understanding of the text?

The average score

and standard deviation for each test group is summarized in Table 2. A one-way ANOVA was

run on the mean scores for each group. The means were found to be significantly different

(F=108.973, p=.000). Post hoc analysis using a Tukey test (alpha =.05) showed that while

the general education group mean was significantly different from the two LEP groups, the

accommodated LEP group mean was not significantly higher than the unaccommodated LEP

group. Controlling for family economic status, years in the U.S., gender, and English

reading ability, we also did not find a significant difference between the means for the

accommodated LEP and unaccommodated LEP groups. Setting the passing rate at 75% correct

(the passing rate of the Minnesota Basic Standards reading test), 62% (n=63) of the

general education group achieved a passing score on the test, while 9% (n=5) of the

accommodated LEP group and 4% (n=2) of the unaccommodated LEP group achieved passing

scores on the test.

Table

2: Mean scores and percentage passing by test group

|

General Education Group |

Accommodated LEP Group |

Unaccommodated LEP Group |

Mean Score |

30.09 |

17.70 |

15.85 |

Standard Deviation |

6.14 |

7.31 |

6.09 |

Group n |

101 |

53 |

52 |

Percent Passing |

62% |

9% |

4% |

In order to compare

student scores to their reading ability in English, the LEP students’ test scores

were correlated with their self-reported reading ability in English from the language

background survey (see Table 3). While this correlation was not significantly different

from zero for the unaccommodated LEP group (r=.232), it was significantly different from

zero for the accommodated LEP group (r=.377) with a moderate to weak correlation. This

correlation, while not high, indicates that it is likely that there is a stronger

relationship between the test scores for the accommodated group and the students’

self-assessment of their reading ability in English than between the unaccommodated LEP

group and their self-reported reading ability.

Table 3: Correlation between scores and reported English reading ability

|

Accommodated LEP Group |

Unaccommodated LEP Group |

Reading ability |

3.96 |

3.60 |

Standard Deviation |

1.08 |

1.22 |

Mean Score |

17.70 |

15.85 |

r |

.377* |

.232 |

n |

51.00 |

52.00 |

* Significant at the .01 level.

To determine which

of the accommodations, if any, had an effect on student scores, raw scores were compared

to accommodated LEP student responses about use of each of the three forms of the test

questions. The students’ cumulative ratings of their accommodation use from the

survey after each of the four passages were used to group them into accommodation usage

groups. Students who did not answer the survey questions after each of the four passages

were excluded from this analysis (n=15 or 16 excluded depending on the question). See

Table 4 for survey results.

Table 4: Cumulative reported accommodation

use and mean test score

Written Spanish Usage

|

Mean |

N |

Standard Deviation |

Always/A Lot |

16.1 |

9 |

5.1 |

Sometimes |

20.6 |

15 |

6.9 |

Never |

22.0 |

13 |

7.9 |

Total |

20.0 |

37 |

7.1 |

Written English Usage |

Mean |

N |

Standard Deviation |

Always/A Lot |

21.2 |

29 |

7.2 |

Sometimes |

17.0 |

8 |

6.8 |

Never |

18.0 |

1 |

-- |

Total |

20.2 |

38 |

7.1 |

Spoken Spanish Usage |

Mean |

N |

Standard Deviation |

Always/A Lot |

14.8 |

5 |

4.3 |

Sometimes |

21.0 |

16 |

7.7 |

Never |

21.3 |

17 |

6.8 |

Total |

20.2 |

38 |

7.1 |

Although none of the

mean scores is statistically different between the students who used one form of the

questions a lot and those who reported never using it, there are some trends that are

interesting. Students using the written Spanish questions “always” to “a

lot” tended to have lower scores (mean =16.1) than those who never used the

accommodation (mean=22.0). The same is true for the students using the spoken Spanish

questions (mean=14.8) as opposed to those never using them (mean=20.2). The trend is the

opposite in the use of the questions written in English. The students using this form of

the question “a lot” to “always” scored higher on the test on average

than those never using the written English questions. These trends are not surprising

since students who depend heavily on the accommodations would be expected to have lower

English proficiency levels and thus rely more on the accommodations than those with higher

levels of English.

Research Question 2: How do students use these

accommodations?

The LEP students

taking the accommodated version of the test were asked how often they used the written

English, the written Spanish, and the spoken Spanish versions of the test questions after

each of the four reading passages. Students reported their usage for each form of the test

questions on a five point Likert scale (see Appendix B). The responses were totaled across

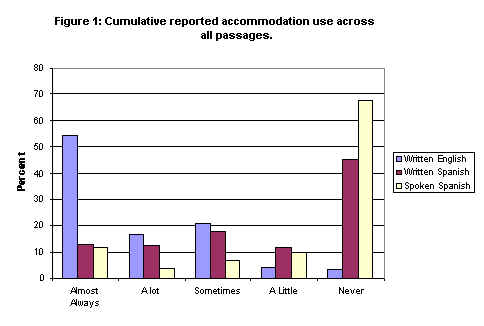

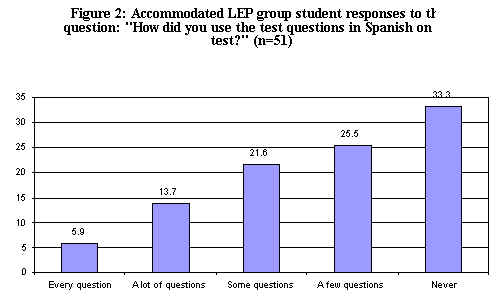

all four reading passages. The percentage of student answers is presented in Figure 1.

Most of the students

reported using the version of the test questions written in English at least a lot of the

time (71.1%). Only 3.3 percent of the time did students never use the test questions

written in English. Use of the questions in written Spanish varied much more with the

greatest number of students (17.9%) reporting that they used it “sometimes.”

Almost 68 percent of the students never used the spoken Spanish version of the test

questions. Only 15.6 percent of the time did students report using the spoken Spanish

version of the questions “always” or “a lot.”

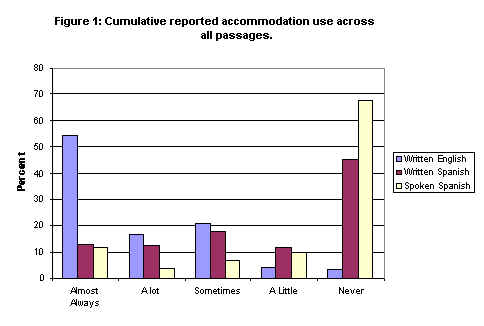

In addition to these

questions, the students in the accommodated LEP group were also asked on an exit card

about their use of the Spanish accommodations overall on the test (see Figure 2). While a

third of the students reported never using any of the accommodations, most of the students

used some form of the translation for some, but not all, of the questions on the test.

Only 5.9 percent of the students reported using some form of the translation for every

question on the test.

In order to investigate more closely how students used the written translation of the test questions offered, each student in the accommodated LEP group was also asked after each passage to answer the following question: “Which would best describe how you used the test questions written in Spanish for this story?” The survey results are shown in Table 5. Overall, about half of the time (48.2%) students reported not looking at the accommodations at all or just looking at them because they were curious. Students reported reading most of the questions in written Spanish and using them to answer the questions 21.1 percent of the time. Students reported using the questions in written Spanish only when they did not understand a word in English 30.7 percent of the time. These data indicate that more students used the written translation as an occasional reference for difficult terminology than read all of the translated questions.

Table 5: Summary of LEP accommodated group

responses to survey question 5.

Survey Question 5:

Which would best describe how you used the test

questions written in Spanish for this story?

A. I just looked at them because I was curious.

B. I looked at them only when I didn’t understand a word in English.

C. I read most of them and used them to answer the questions.

D. I didn’t look at them at all.

|

Passage 1 |

Passage 2 |

Passage 3 |

Passage 4 |

Total |

|||||

|

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

Count |

% |

A |

9 |

21.4 |

9 |

21.4 |

8 |

19.0 |

6 |

15.0 |

32 |

19.3 |

B |

16 |

38.1 |

10 |

23.8 |

12 |

28.6 |

13 |

32.5 |

51 |

30.7 |

C |

9 |

21.4 |

9 |

21.4 |

11 |

26.2 |

6 |

15.0 |

35 |

21.1 |

D |

8 |

19.0 |

14 |

33.3 |

11 |

26.2 |

15 |

37.5 |

48 |

28.9 |

Total |

42 |

100.0 |

42 |

100.0 |

42 |

100.0 |

40 |

100.0 |

166 |

100.0

|

Further analyses

were conducted in order to gain a better understanding of how the students used the

accommodations. The accommodated LEP group was broken into two subgroups: those scoring

above 24 (higher scoring students) on the test and those scoring 24 or below on the test

(lower scoring students). A follow-up linear contrast showed that the higher scoring

students were significantly less likely to use the written Spanish accommodations than the

lower performing students (t=2.021, p=.051). There was not a significant difference in the

use of the spoken Spanish accommodation between the two groups (t=1.611, p=116).

To determine whether

students using the written Spanish accommodation were scoring higher on the test than

students who were not, a factorial ANOVA was run in order to examine the following three

factors: self-reported English reading proficiency, use of the written Spanish

accommodation, and test score. The results of the simple effects analysis are shown in

Table 6.

Table 6: Simple effects for use of written

Spanish accommodation by self-reported English reading proficiency level

English Reading Proficiency |

Use of Written Spanish Accommodation |

N

|

Mean Test Score |

Standard Error |

95% Confidence Interval |

|

Lower

Bound |

Upper Bound |

|||||

High |

Moderate to High Use |

9 |

18.44 |

2.267 |

13.833 |

23.056 |

Low Use |

21 |

22.19 |

1.484 |

19.171 |

25.210 |

|

Low to Moderate |

Moderate to High Use |

3 |

17.33 |

3.926 |

9.345 |

25.321 |

Low Use |

4 |

14.00 |

3.400 |

7.082 |

20.918 |

|

The mean test scores

between the groups in this analysis were not statistically significant. This is not

unexpected considering that the number of students in some of the groups is so small.

These small numbers make the results of this simple effects analysis tenuous at best. They

are presented here because an analysis like this might be useful in future studies as a

way of gaining a richer understanding of how students use accommodations. It should also

be noted that the English reading proficiency rating used in this study was a self-rating

by the students. This type of measure produced many students rating themselves at the high

end of the scale. Using a better measure of proficiency might produce more meaningful

results. Not enough of the students in this study used the spoken Spanish accommodation to

run a comparable analysis with that accommodation.

Research Question 3: Will students use the

accommodations if they are made available?

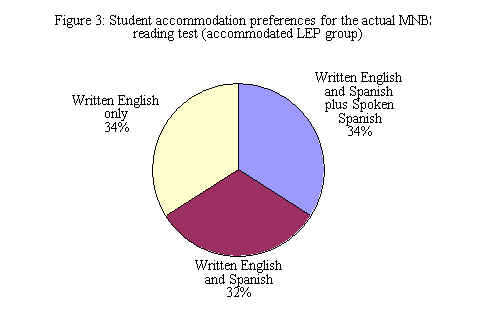

At the end of the

test, students in the accommodated LEP group were asked which form of the test they would

choose to take if given the choice during the actual Minnesota Basic Standards reading

test: a version with questions in spoken Spanish and written Spanish and English, a

version with only written Spanish and English questions, or a version with the questions

only in written English. The responses were almost evenly distributed across the three

choices (see Figure 3). About 34.2 percent would choose the accommodated version of the

test with the questions in written English, written Spanish, and spoken Spanish. About

31.6 percent of the students would choose a version of the test with questions in written

English and written Spanish, but no tape and 34.2 percent of the students would choose the

version of the test with the test questions presented only in written English.

Research Question 1: Does giving students reading test

questions in both English and Spanish (both aurally and in writing) enable them to better

demonstrate their understanding of the text?

While the

accommodated LEP group did have a higher mean score (17.70) than the unaccommodated LEP

group (15.85), the mean scores of the two groups were not significantly different. Both of

these groups had average scores that were significantly lower than the general education

group mean score (30.09). These data indicate that giving the accommodations to a group of

LEP students of varying proficiencies did not help boost their scores significantly.

Taking family economic status into account, the difference in the mean scores between the

accommodated and unaccommodated LEP groups in this study was even smaller. These data

could be interpreted in different ways. We know from student surveys that about one-third

of the accommodated group never used the accommodations to any great extent, a factor that

would limit any impact the accommodations had on the group mean. On the other hand, the

small difference in mean scores could also indicate that the accommodations did not have a

great impact on the students’ scores overall.

While the

accommodations did not produce a big jump in student scores, one must also take into

account that the accommodations are not meant to give the students an advantage over

students not receiving the accommodations, but instead to help reduce the disadvantage

that LEP students face when taking standardized tests normed on monolingual

English-speaking populations. The data from this study do not indicate that the

accommodations gave the LEP students a significant advantage over their native

English-speaking peers.

Even though we did

not find a significant overall difference between the accommodated and unaccommodated LEP

groups, the scores for the accommodated LEP group were significantly correlated with their

self-reported English reading ability while the unaccommodated LEP students’ scores

were not. This may indicate that the students who had the accommodations available to them

were better able to demonstrate their English reading ability than those who were not able

to use the accommodations. Although not a strong correlation for the accommodated group,

the statistically significant finding indicates that more research in this area is needed

in order to determine whether the translated questions accommodation could actually

increase the validity of standardized reading tests for some LEP students.

Of the accommodated

LEP students, the ones who reported using either of the Spanish language accommodations a

lot tended to score lower than those who used the accommodations sometimes or not at all.

While none of these differences were significant, they show a trend that students relying

heavily on the first language accommodations probably have lower reading proficiencies and

the accommodations help them only a limited amount. The test score still reflects their

low reading ability. On the other hand, students using the Spanish accommodations had an

average raw score closer to students who reported never using the accommodations. Thus,

students who did not depend heavily upon the accommodations tended to score about the same

as students who have English proficiencies high enough to think that they do not need the

accommodations.

Overall, providing

the reading test questions in both written and spoken Spanish did not produce

significantly higher test scores for the LEP students in this study. The test scores of

the accommodated LEP group, while not significantly higher than the unaccommodated LEP

group, did better reflect the students self-rating of their English reading abilities. It

seems, however, that the question of the accommodations allowing the students to better

demonstrate their reading abilities in English by allowing them to better understand the

questions being asked depends on how students use the accommodations and what their

proficiency level is. The students scoring higher on the test tended not to use the

accommodations or to use them only sometimes. The students who depended heavily on the

accommodations tended to score lower on the test. Both of these factors, a reliance on the

Spanish accommodations and the low test scores, are likely a reflection of their low

English proficiency level.

Research Question 2: How do students use these

accommodations?

In order to better

understand the effectiveness of the accommodations, this study examined student reports on

how they used the accommodations. Qualitative data from Phase 1 of this study revealed

that students tended to primarily use one version of the written test questions (either

English or Spanish) and then refer to the other version when difficulties were encountered

(Liu, Anderson, Swierzbin & Thurlow, 1999). The students in the first part of the

study also made very little use of the test questions in spoken Spanish. The results of

Phase 2 of this study generally confirm these findings. Students reported using the

written English version of the test questions the most and the spoken Spanish version of

the questions the least. The use of the written Spanish questions varied.

When students were

asked how they used the test questions written in Spanish, 30.7 percent of the time

students reported looking at them only when they did not understand a word in English.

Students reported reading and using most of the questions written in Spanish 21.1 percent

of the time. The rest of the time students reported just looking at the questions because

they were curious (19.3%) or never looking at them (28.9%). Although the greatest

percentage of students answering this question used the Spanish accommodations as a

reference, how students use the translations seems to vary. This is not surprising

considering that the students in this study reflected a wide variety of English

proficiencies. The fact that only 5.9 percent of the students reported using the Spanish

language accommodations on every question indicates that very few students were using the

Spanish versions of the test questions as their primary source.

While not depending

on the translations for every question, most students did use one or both versions of the

Spanish translations to answer some of the questions. Perhaps most important, not all LEP

students chose to use the translated questions when they were available. Of the students

who did use the translated questions, most used the written form of the questions

(presumably because they were literate in their first language or did not feel comfortable

using the accommodation).

Students scoring

higher on the reading test were significantly less likely to use the accommodations than

were their lower scoring peers. This is not surprising since one would expect that the

students with higher English reading proficiencies would be less likely to need the

accommodations. Although not significantly different, students with high self-reported

English reading proficiencies who did not use the accommodations very much scored higher

on the test than high-proficiency students who used the accommodations a lot. Of the

low-proficiency students, those who reported using the accommodations scored higher than

those who did not use them. While these data may not be reliable due to the low numbers of

students in some categories and the fact that self-report was used for gauging English

reading proficiency, the type of analysis using these three factors might be of use in

future studies. These data also reflect the wide variety of language proficiency levels

among these students.

Research Question 3: Will students use the

accommodations if they are made available?

When the students

given the bilingual version of the test were asked which version of the test they would

choose if they had a choice when taking the actual Basic Standards reading test, about one

third of the students reported preferring an English-only version, about one third

reported preferring a bilingual version with no tape, and one third reported preferring a

bilingual version of the test that also had the questions provided aurally in Spanish.

These data are consistent with student exit cards where a third of them reported never

using the Spanish accommodations.

Although one third

of the students reported never using any form of the Spanish accommodations and one third

of the students responding to the test preference question reported preferring an

English-only reading test, only 9 percent of the accommodated LEP students achieved a

passing score of 75% correct on the test. Even though the test given in this study was

very difficult for the vast majority of the LEP students, a third of these students would

not choose to use bilingual accommodations if given the choice. The current study did not

investigate why this is the case. Some possibilities might be that students do feel more

comfortable working in only one language, that they did not find these accommodations to

be of use, that they do not know how to use translations effectively, or that they feel

some sort of pressure from their peers or family to work only in English. The bulk of the

students in the accommodated group had been in the United States at least nine years. It

is possible that during this time their Spanish language skills were not developed or

maintained and because of this native language accommodations were not beneficial to them.

Even though one

third of the students chose not to use the accommodations, it should be noted that the

students participating in this study had never taken an actual Minnesota Basic Standards

test. The students took the official test for the first time a few months after this study

was conducted. If students do not pass the test in eighth grade, they have several

additional opportunities to take the test. Students may be denied a diploma if they do not

pass the tests by the end of twelfth grade. It is possible that students taking the test

in eleventh or twelfth grade, when the stakes are higher, might view accommodations

differently from the eighth grade students in this study.

The data also

demonstrate that the majority of the students offered the translated test questions in

this study did find them to be of some use. The

usefulness of the accommodation depends on the student. Often times, decisions about the

accommodations students receive are made on a class, school, or district basis. This study

indicates that the usefulness of accommodations varies and the decision of whether to

provide an accommodation should be made on an individual basis whenever possible. Making

accommodation decisions on an individual level can ensure that each student is receiving

the most appropriate version of the test to best demonstrate his or her abilities. In

addition, there needs to be more research done on what type of student native language

accommodations help the most. This study indicates that students with moderate proficiency

in English and some level of reading proficiency in their native language might be more

likely to use and benefit from these accommodations.

Limitations of the Study

The greatest

limitation to this study is the small sample size. A study with a greater number of

participants might allow researchers to detect more subtle differences between groups of

students while taking into account all of the variables that can impact the performance of

LEP students. A better measure of students’ first and second language proficiency is

also needed. Independent measures of proficiency would allow one to check the reliability

of student self-reported data. Finally, it would be ideal to try out the test

accommodations using an administration of a statewide reading test with participants from

a variety of language backgrounds.

Future Research

Future research

questions that need to be addressed include:

•

Would providing translated test questions to a larger group of

students demonstrate that this accommodation has an impact on student scores?

•

Students of what proficiency level would most benefit from using

translated test item accommodations on standardized reading tests?

•

Are students familiar with using first language accommodations in

their reading classrooms?

•

How would LEP students from language backgrounds other than Spanish

use similar accommodations? How would these accommodations affect their scores?

•

Why do students who are still receiving ESL services choose not to use

first language accommodations?

•

Would students be more apt to use a taped version of the test

questions if they were being tested in an individual setting?

•

Can technology, such as computer administered tests, help reduce the

social factors that might influence the use of these accommodations?

•

If students are using translations as a reference when they encounter

difficult vocabulary, would the use of a dictionary be a more appropriate accommodation?

Policy Recommendations

Accommodations and

modifications to a standardized test are often thought of as something that can be given

to a group of LEP students to help them pass the test. However, the issues raised by the

use of translations are much more complicated. While translations appeared to be useful in

helping some native Spanish-speaking students in this study to better demonstrate their

English reading ability, the translations did not significantly increase the number of

students passing the test. Further studies need to be done with students from other

language backgrounds and the reader is cautioned against generalizing these research

findings to non-Spanish speaking students. Spanish and English contain many “cognates,”

both deriving from Latin; therefore, certain words and phrases may look similar in the two

languages. Asian languages, for example, do not have this kind of similarity to English

and students who speak an Asian language may have a completely different experience using

a dual language reading test. Furthermore, students from other language backgrounds may

have different beliefs about the desirability of using a translated reading test.

With these cautions

in mind, the following recommendations for policymakers can be made:

• Accommodations

and modifications are not a guaranteed formula for helping low-achieving LEP students pass

a standardized test. As demonstrated by the translated test used in this study, an

accommodation or modification may allow the student to better demonstrate particular

skills by decreasing the English language load. An accommodation cannot make up for

content instruction that students have not yet received or for skills that are weak. When

assessments are chosen, attention to the needs of LEP students must be given up-front to

determine whether the test is appropriate for this group as well as for their native

English speaking peers. Educators and policymakers must also make sure the test aligns

with the content and skills being taught to LEP students.

• Translations

are not appropriate for every speaker of a particular language and not every student wants

or will use an accommodation like this on a large-scale assessment. A standardized method

of determining which students are most likely to benefit from an accommodation is

desirable. Results from native language proficiency and English language proficiency

assessments would be indicators of the ability to benefit from a translation, but they

should not be the only indicators. Some students who are not proficient readers in their

native language may find that their test anxiety is reduced by the presence of the native

language on the test booklet or on a cassette tape. Students and families should have

input in deciding which accommodations will be offered to an individual student. For the

majority of language groups present in the LEP student population there may not be a

standardized test of academic language proficiency in their first language. In these

cases, other types of indicators of academic language proficiency in the native language

need to be developed.

• Students

in this particular study tended to use the translation like a dictionary or glossary to

look up unknown words or phrases. Few students actually used the entire text in both

languages, indicating that future study is needed about the feasibility and desirability

of using glossaries or dictionaries on standardized reading tests. Given the cost of

producing translated tests, glossaries or dictionaries may be a more effective use of

resources.

•

The students’ willingness to use an accommodation, and

their ability to benefit from one, appears to be affected by the testing environment and

the students’ proximity to peers who are not using the accommodation when taking the

test. Students who are offered an accommodation may need to be tested individually or in a

small group of students who will all be using a particular accommodation so that they do

not feel pressured.

• Studying

the impact of an accommodation in a mock testing situation provides useful information

about the feasibility and desirability of the accommodation. However, the true usefulness

and effectiveness of the accommodation may not be known until students are actually in a

high-stakes testing situation where there are consequences for not passing the assessment.

In this particular study, more students said they would like the option to use an

audiotape in the native language on the real assessment, than actually tried the audiotape

on the mock test used for the research study. The closer students get to being denied a

high school diploma because they have not passed the test, the more likely they may be to

want to use a translated test.

• Limited

English proficient students would greatly benefit from a process of individualized

decision making and planning perhaps similar to the IEP process in which special education

students participate along with their parents and teachers. As a part of the IEP process,

attention is given to the type of instructional supports students receive in the classroom

that would benefit them in a testing situation. In a testing situation, LEP students tend

to be treated as one group with similar needs and this study has demonstrated that even

within one language group the ability to benefit from a particular accommodation varies by

student.

References

Abedi, J., Lord, C.

& Hofstetter, C. (1998). Impact of selected

background variables on students’ NAEP math performance. CSE Technical Report 478. Los Angeles, CA: Center

for Research on Evaluation, Standards and Student Testing (CRESST), Center for Study of

Evaluation, University of California. Retrieved from the World Wide Web:

http://www.cse.ucla.edu/CRESST/Reports/TECH462.PDF

Aguirre-Munoz, Z.,

& Baker, E. (1997). Improving the equity and

validity of assessment-based information systems. CSE Technical Report 462. Los

Angeles, CA: Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards and Student Testing (CRESST),

Center for Study of Evaluation, University of California. Retrieved from the World Wide

Web: http://www.cse.ucla.edu/CRESST/Reports/TECH462.PDF

Butler, F., &

Stevens , R. (1997). Accommodations strategies for

English language learners on large-scale assessments: Student Characteristics and other

considerations. CSE Technical Report 448. Los Angeles, CA: Center for Research on

Evaluation, Standards and Student Testing (CRESST), Center for Study of Evaluation,

University of California. Retrieved from the World Wide Web:

http://www.cse.ucla.edu/CRESST/Reports/TECH448.PDF

Council of Chief

State School Officers (1999, Fall). Data from the

annual survey: State student assessment programs, Volume 2. Washington, DC: Author.

Garcia, G. E.

(1991). Factors influencing the English reading test performance of Spanish-speaking

Hispanic children. Reading Research Quarterly, 26

(4), 371-392.

Liu, K., Anderson,

M., Swierzbin, B., & Thurlow, M. (1999a) Bilingual

accommodations for limited English proficient students on statewide reading tests: Phase 1

(Minnesota Report 20). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, National Center on

Educational Outcomes.

Liu, K., &

Thurlow, M. (1999b) Limited English proficient

students’ participation and performance on statewide assessments: Minnesota Basic

Standards Tests in reading and math, 1996-1998. (Minnesota Report 19). Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Liu, K., Thurlow,

M., Thompson, S., & Albus, D. (1999c, January). Participation and performance of students from

non-English language backgrounds: Minnesota’s 1996 Basic Standards Tests in reading

and math. (Minnesota Report 17). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, National Center

on Educational Outcomes.

Minnesota Department

of Children, Families and Learning. (2000) Basic

Standards Reading Test specifications. Retrieved from the World Wide Web:

http://cfl.state.mn.us/GRAD/readspecs.html

National Center for

Educational Statistics (NCES). (1992). Language

characteristics and academic achievement: A look at Asian and Hispanic eighth graders in

NELS:88. (NCES publication No. 92-479). Washington, DC: Author.

National

Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education. (1997). High

stakes assessment: A research agenda for English language learners: Symposium summary. Retrieved

from the World Wide Web: http://www.ncbe.gwu.edu/ncbepubs

Rivera, C.,

Stansfield, C. W., Scialdone, L., & Sharkey, M. (2000). An analysis of state policies for the inclusion and

accommodation of English language learners in state assessment programs, 1998-99.

Arlington, VA: Center for Equity and Excellence in Education, George Washington

University.

Rivera, C., &

Stansfield, C. (1998). Leveling the playing field for English language learners:

Increasing participation inn state and local assessments through accommodations. Ed. R.

Brandt. Assessing student learning: New rules, new

realities. Arlington, VA: Educational Research Service, 65-92.

Stansfield, C.

(1996). Content assessment in the native language

(ERIC/AE Digest Series EDO-TM-96-02). Retrieved

from the World Wide Web: http://ericae.net/digests/tm9602.htm

Stansfield, C.

(1997). Experiences and issues related to the format of bilingual tests: Dual language

test booklets versus two different test booklets. (ERIC Clearinghouse No. TM028299). (ERIC

no. ED419002).

Thurlow, M., Liu,

K., Erickson, R., Spicuzza, R., & El Sawaf, H. (1996). Accommodations for students with limited English

proficiency: Analysis of guidelines from states with graduation exams (Minnesota

Report 6). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Appendix A

Format of the Questions on the Bilingual

Reading Test

ENGLISH

1. What

do roadside stands have to offer that supermarkets DO NOT?

A. very

fresh produce

B. much lower prices

C. personal attention by salespersons

D. a larger variety of products

2. What do the first few paragraphs of the article

tell the reader about Janet Kading?

A. She's a very funny woman.

B. She's an unusually hard

worker.

C. She likes her job and does it

well.

D. She is kind and courteous.

3. How

are the Sponsel and Wagner stands alike?

A. Both are huge operations, with many

employees.

B. Both offer baked goods.

C. Both sell apples only.

D. Both serve lunches to visitors.

SPANISH

1. ¿Qué

es lo que ofrecen los puestos en la carretera que los supermercados no ofrecen?

A. frutas y verduras muy frescas

B. precios mucho más baratos

C. atención personal de los vendedores

D. una variedad más grande de productos

2. ¿Qué es lo que dicen los primeros párrafos del

artículo al lector acerca de Janet Kading?

A. Es una mujer muy simpática.

B. Es una mujer muy trabajadora.

C. Le gusta su trabajo y lo hace bien.

D. Es muy amable y cortés.

3. ¿En qué se parecen los puestos de Sponsel y

Wagner?

A. Los dos son negocios muy grandes con muchos

empleados.

B. Los dos ofrecen productos de panadería.

C. Los dos venden manzanas únicamente.

D. Los

dos sirven comida a los visitantes.

Appendix B

Questions Given to Accommodated LEP Students After Each Reading Passage

Please answer a few

questions about the passage you have just read. Use

a pencil to fill in the bubble that best answers each question. Thank you.

1. Did you know something about the subject of this

story before you read it?

A. Yes

B.

No

2. How often did you use the test questions written

in Spanish?

A. Almost always

(75-100%)

B. A lot

(50-75%)

C. Sometimes

(25-50%)

D. A little (1-25%)

E. Never (0%)

3. How often did you use the test questions written

in English?

A. Almost always

(75-100%)

B. A lot

(50-75%)

C. Sometimes

(25-50%)

D. A little (1-25%)

E. Never (0%)

4. How often did you use the test questions spoken

on the tape in Spanish?

A. Almost always

(75-100%)

B. A lot

(50-75%)

C. Sometimes

(25-50%)

D. A little (1-25%)

E. Never (0%)

5. Which would best describe how you used the test

questions written in Spanish for this story?

A. I just looked at them because I was curious.

B. I looked at them only when I didn’t

understand a word in English.

C. I read most of them and used them to answer the

questions.

D. I didn’t look at them at all.

_______________________________________________________

(Question #6 was

asked only at the end of the test.)

6. If you could use a version of the Basic Standards

Reading Test to take next winter, which would you choose?

A. A test with questions written in English and

Spanish with a tape in Spanish.

B. A test with questions written in English and

Spanish, but no tape.

C. A test with questions written only in English.