Prepared by Kristin Liu, Deb Albus, Martha Thurlow, John Bielinski, and Rick Spiccuza

This document has been archived by NCEO because some of the information it contains is out of date.

Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Liu, K., Albus, D., Thurlow, M., Bielinski, J., & Spiccuza, R. (2000). Factors related to the performance of LEP students on Basic Standards Tests (Minnesota Report No. 27). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/MnReport27.html

Large-scale assessment data are often used along with other

information to plan school improvement efforts. These improvement efforts, however, may

lack important information about student needs because state assessment reports and

research on large-scale assessments tend to treat students with non-English language

backgrounds or with limited English proficiency as one large group with one set of needs.

For such students, educational researchers have recommended disaggregating test scores and

other data by language group, by type of accommodation used, and by whether students are

receiving English as a second language (ESL) services or not (August, Hakuta, Olguin &

Pompa, 1995; National Center for Education Statistics, 1996). These recommendations are

supported by recent research that reported differences in test scores among students with

different non-English language backgrounds, and between those who were receiving ESL

services and those who were not (Liu, Thurlow, Thompson & Albus, 1999). In addition,

Cota (1997) found that the educational history of students with limited English

proficiency had an effect on their current academic performance. Other factors which may play a role in

students’ performance include their socio-economic status, mobility, length of time

in the U.S., and length of time in U.S. schools. Educators

and policymakers need to know which factors significantly affect student performance so

they can plan to meet students’ complex and diverse needs.

This report summarizes data that were collected during 1996-98 to

examine more in depth the factors related to the performance of students with non-English

language backgrounds in Minnesota state assessments.

Definitions of the groups of students that were studied are given, the

Minnesota assessment is characterized, and the factors that were analyzed are described.

All the students in this study had a non-English language

background (NELB). A NELB student is a

student who speaks or has had significant exposure at home to a language other than

English. Defining students as

“NELB” does not necessarily mean they have limited English proficiency, nor does

it differentiate between students who may need ESL or bilingual services now, or who may

have received services in the past. In this report, a student with limited English

proficiency (LEP) is defined as a NELB student who has met the Minnesota criteria for

being eligible for ESL services. LEP students

may or may not be receiving services. The subgroup of LEP students who are receiving

services are defined in this report as ESL students.

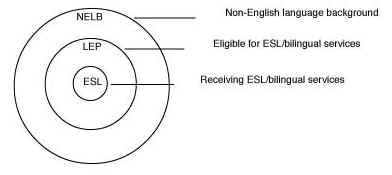

These definitions are shown graphically in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Definitions of Non-English Language Background Students by Subgroups

In Minnesota, students must pass Basic Standards Tests (BSTs),

which are minimum competency tests of reading, mathematics, and writing, to earn a high

school diploma. Students take the reading and

mathematics portions first in the 8th grade, and may repeat them one to two times per year after that

until they pass with a 75% correct score or higher. The

writing test is administered for the first time in 10th grade. These requirements apply to all students including NELB

students. While there has been some attention paid to ESL students (i.e., those receiving

services), the needs of NELB students not receiving services have not received much

attention when the state examines the relationship between BST scores and school

improvement efforts. This is a significant

omission since school and program improvement is among the major goals when administering

these and other tests.

This study was conducted using a record review approach to

analyze student background characteristics that affect participation and performance of

various subgroups of NELB students on Minnesota’s Basic Standards Tests. We sought to examine the relationships between

test performance and mobility, educational history, home language, receiving ESL services,

and English language proficiency test scores. An urban district and a rural district

participated in this study. Two high schools were chosen from each district along with one

junior high school and alternative school sites.

Site Descriptions: District One

District One’s junior and senior high schools were located

in a rural town with a population of 19,000. The student population consisted of

Caucasians (79.7%), Hispanics (17.5%), African-Americans (1.0%), Asians (.7%), and others

(1.1%). A total of 1, 858 students received free or reduced price lunch in the district.

The number of NELB students attending the junior high, senior high, and alternative

learning center was 291. Of these, 161 students in grades 7-12, were identified as having

limited English proficiency, and 129 were receiving ESL or bilingual education services.

The average student-teacher ratio in ESL/bilingual education

classes in grades 7-12 was 10:1. There were 13 ESL licensed teachers. None of the regular

education teachers taught ESL or bilingual classes. Four educational assistants worked in

ESL/bilingual education.

The average time students spent in ESL services depended on the

student’s grade level and English proficiency. In the junior high school, time in ESL

classes varied between 1-3 class periods a day. In the senior high, all students receiving

ESL services did so for one block a day (with 4 blocks making up a day).

District 1 Alternative Sites

One alternative site had 90 students with 42% eligible for free

or reduced priced lunch. Twenty-two percent of these students received ESL or bilingual

services. There was no information available

for teacher staff in that year. The average daily attendance was 42 students. The

Inter-district Mobility Index was 50.9, and the Intra-district Mobility Index was 51.8.

These indicies showed that approximately half of the students moved each year, either

between districts or within the district.

For the second alternative site there was an enrollment of 27

students with 78% eligible for free or reduced priced lunch. Thirty percent of the

students received LEP services, and all of them were receiving special education services.

The average daily attendance was 24 students. The Inter-district Mobility Index was 74.1

and the Intra-district Mobility Index was 55.6. Similar to the first alternative site,

there was no information available on teaching staff.

Site Descriptions: District Two

District Two’s middle school served grades 6 through 8, and

was located in a Midwest metropolitan city with a population of 2.68 million. As of fall

1997, the middle school population was 725 students. Approximately 76% had free lunch

status. NELB students made up 29% of the student population. The ethnic background of this

student body was Asian students (21%), African American (36%), Hispanic (14%), and

American Indian (6%); 23% of the students had other ethnic backgrounds, predominately

Caucasian. A total of 209 students was identified as eligible for ESL or bilingual

education services. Of these, 197 students in 7th and 8th grades received services.

The bilingual education program in this District Two middle

school was both a maintenance bilingual education program and a transitional bilingual

program. Students were dismissed from services either by early exit (less than 3 years) or

late exit, depending on student needs. ESL programming consisted of either one scheduled

class in one or two school days or a newcomer remedial class. On average, students had

participated in ESL and/or bilingual services for 2 years.

The average student-teacher ratio in ESL/bilingual classes was

16:1, which compared to an average student-teacher ratio in regular education classes of

24:1. There were five bilingual education teachers and three ESL teachers in the

ESL/bilingual education program. Two of these teachers were licensed bilingual education

teachers and two were licensed ESL teachers. One teacher was a regular education teacher

with a provisional license. In addition to this teaching staff, there were three

ESL/bilingual educational assistants working in the program.

District Two’s senior high had a total of 438 students

receiving ESL/bilingual services, with 264 of these being in grades 9 and 10. The average

student-teacher ratio for regular education classes and the ESL/bilingual program is 25:1.

The school had six licensed bilingual teachers and eight teachers licensed in ESL. Also,

there were three educational assistants working in the ESL/bilingual program. The

bilingual program was Dual Immersion/2-way bilingual education with no “exit

program.”

Six research staff collected data over a span of 1-1/2 years.

Although staff aimed to collect all data from students’ cumulative files (Cum F),

this was not possible due to incomplete data. Supplemental information was collected from

the districts’ databases, ESL/bilingual teacher files, and ESL coordinator reports.

Of the 646 files reviewed across all sites, there were 99 files

that could not be used due to extreme lack of data, (e.g., only student name and free or

reduced lunch indicator were available). Another 22 files were unable to be used due to

lack of information such as an identification number in the Minnesota Automated Reporting

Student System. It should also be noted that the record review for 10th graders started at one of the sites was not completed due to

time constraints. The reviewed 10th grader files are not included in this report. The total number

of files reviewed and used by district and site are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Files Reviewed and Used by Site

|

District

1 |

District

2 |

||||

|

Sr.

High (9th

only) |

Jr.

High |

ALC

(1) |

ALC

(2) |

Sr.

High |

Jr.

High |

Files

Reviewed |

64 |

47 |

21 |

5 |

390 |

119 |

Files

used |

62 |

45 |

8 |

0 |

298 |

115 |

Table 2 shows the types of information that were collected and

the sources from which data were collected across sites. It is interesting to note that

several pieces of information were available from two sources or more, but that some

information was only available from one source. The sources of information were not

necessarily the same in the two districts.

Table 2. Information Collected and Sources

Information

Collected |

District

1 Sources |

District

2 Sources |

|||||

|

Cum

File |

ESL

File |

District |

ESL

Coord |

Cum

File |

District |

ESL

Coord |

Home

Language |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

Gender |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

Birthdate |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

Graduation

Year |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

ESL

Services |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

BST

Scores |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

Economic

Indicator |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

Country

of Origin |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

Time

in U.S. |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

Time

in U.S. schools |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Time

in District |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

School

Changes |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Achievement

tests |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

Language

Proficiency Tests |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

Note: ESL file data were from a set of records kept by ESL teachers. These data were repetitive of data from cumulative files and were used to help fill in data possibly missing from cumulative files. ESL Coordinator data involved information about student placement which in some, but not all cases, was provided at the district level.

Issues in Collecting Data

Data collectors encountered several difficulties while collecting

data. Because many files were incomplete or contained no records from previous schools, it

was difficult to obtain information on academic history, past or current LEP or bilingual

status, and current grade placement. In other files, there was an abundance of other

information that reviewers needed to look through to find the data relevant to this study.

Some information that was available was difficult to interpret because of a lack of

clarity in the definition of language minority students and conflicting information on

home language forms. Other files lacked educational history, test scores and transcripts,

usually due to high mobility of students. Even when data were available, other problems

arose with interpreting them. For example, it was often difficult to calculate moves

between schools within a district because of school name changes or restructuring of

grades in schools. More specific information on data issues encountered in this study is

reported in Liu and Thurlow (2000).

Despite the attempts of data collectors to maintain consistency

throughout the data collection process, changes in procedures were unavoidable. This

occurred, for example, when collecting data on the students’ LEP status. Originally

the plan was to collect LEP status data from the cumulative file. However, student

cumulative file data were incomplete and hard to interpret. Thus, data collectors decided

to consult ESL coordinators’ reports and school district data offices for information

on ESL program start dates in order to identify students as LEP.

Data collectors had to select among the numerous data entries in

cumulative files. For example, in calculating the number of school changes it was decided

that one change (from elementary to junior high or from junior high to senior high) was

the norm for students. Data collectors recorded the number of transfers and later

categorized them into “less than three” and “three or more.” In

addition, for one district in our study, some schools had additional possible changes,

particularly in K-2 and K-4 schools; these were counted as school transfers.

Data Collection Reliability

During data collection, every fifth file (20%) was independently

reviewed a second time by a project staff member who had not taken part in the first

review. Then the first and second file reviews were analyzed for accuracy. Inter-rater

agreement on five types of information was checked: home language, most recent test scores

on major standardized achievement tests and language proficiency tests, all the Basic

Standards Tests scores for 1996 and 1997, and English as a Second Language (ESL) status.

For standardized achievement tests, inter-rater agreement was checked only for the most

common tests.

The data were checked for agreement in two ways. First, all items

coded by either the first data collector or the reliability check person were compared.

This comparison is found in Table 3 under “All items.” The 91% agreement was

high, perhaps because this analysis counted data that were missing. Because it is

relatively easy to get agreement that data are missing, this agreement estimate gives an

inflated index of agreement.

Table 3. Agreement Rate

All

items |

Existing

Items

|

||

Number compared

|

1048 |

Number compared

|

419 |

Number

agreed |

957 |

Number

agreed |

330 |

Percent

agreed |

91% |

Percent

agreed |

79% |

A second agreement check compared only those items where at least

one reviewer found information in a file. This percentage, under “Existing

items,” is lower at 79%. Still this is an acceptable agreement rate.

Some of the difference in agreement might be due to the fact that

the decision about how to collect ESL services changed during the data collection process,

causing some inconsistency in the collection of these data. All inconsistencies were

resolved by choosing the more official cumulative file data over data from less official

sources.

Findings were examined in several ways. First, we looked at the

missing data. Next, we analyzed BST performance as a function of several student

characteristic variables, including (1) demographic characteristics, (2) home language,

(3) multiple time test takers, (4) ESL and bilingual services, and (5) NRT and language

proficiency test scores.

Missing Data

Missing data were a significant problem in this study. For

example, records often did not contain data on what kinds of services were received by

students (ESL/bilingual) or whether students were continuing to receive them. Across

sites, we were not able to find gender or “free or reduced lunch status” (an

indicator of socioeconomic status) for 1-5% of the students. Missing data created very

significant problems for looking at number of school changes and number of years in U.S.

schools. On these variables, there were no data for 40-86% of the students.

Demographic Characteristics and BST Performance

Characteristics for students across all sites, for those students

whose files could be used, are provided in Table 4. Different Ns for categories (i.e.,

Gender) are due to missing or conflicting data.

Table 4. Demographic Characteristics of Students Across All Sites

Characteristic

|

|

Count

|

Percent |

Gender

|

Male

|

262 |

51.5% |

Female |

247 |

48.5% |

|

Total |

509 |

100.0% |

|

Grade

|

8 |

160 |

30.5% |

9 |

218 |

41.6% |

|

10 |

146 |

27.9% |

|

Total |

524 |

100.0% |

|

School

Changes |

<

3 |

144 |

84.2% |

=

3 |

27 |

15.8% |

|

Total |

171 |

100.0% |

|

Home

Language |

Hmong |

111 |

30.4% |

Laotian |

16 |

4.4% |

|

Spanish |

134 |

36.7% |

|

Somali |

39 |

10.7% |

|

Other |

65 |

17.8% |

|

Total |

365 |

100.0% |

|

Lunch

Status |

Pay

in full |

73 |

14.4% |

Reduced |

23 |

4.5% |

|

Free |

412 |

81.1% |

|

Total |

508 |

100.0% |

The students in our sample included students in grades 8, 9 and

10, most of whom received free or reduced lunch support and who moved fewer than three

times after coming to the U.S. The students had a variety of home languages, but most were

Hmong and Spanish. These data are not limited to students who had been in a district a

certain number of years, who had been in the U.S. or in U.S. schools a specific number of

years (see Table 5).

Table 5. Years in District, U.S. Schools, and U.S. for Students Across All Sites

Characteristic |

Valid

N |

Mean |

Median |

Range |

Time in District

|

363 |

3.54 |

2.5 |

0 to 12 |

Years

in U.S. Schools |

220 |

5.67 |

6.5 |

0 to 14 |

Years

in U.S. |

320 |

7.80 |

6.5 |

0

to 17.5 |

While the average time in district was 3.5 years, the time varied

for individuals from 0 to 12 years in district. The average length of time in U.S. schools

was 5.6 years and the average length of time in the U.S. was 7.8 years.

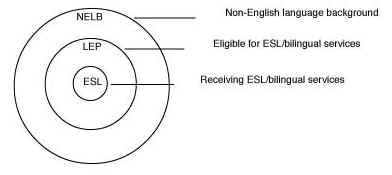

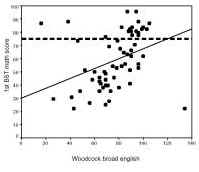

We combined the students in Districts 1 and 2 to analyze the relationships between characteristics and BST performance. Significant correlations found were for “Years in U.S. Schools” and “School Changes.” ‘Years in U.S. schools’ data are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Years in U.S. Schools by BST Scores

Analyses of relationships between student background

characteristics and BST performance revealed that the number of years a student had been

in U.S. schools was moderately related to BST performance (rread=.479; rmath=.497).

We examined the effect of the number of school changes on BST

performance. After controlling for gender, free/reduced lunch status, time in district,

and the number of years in U.S. schools, we found a significant difference in the

performance of students with fewer than 3 school changes on the reading test compared to

students with 3 or more changes (p=.04). The mean performance of students with fewer than

three school changes (57.6) was significantly higher than that of students with 3 or more

changes (42.0). The difference on the math test was not statistically significant.

Home Language and BST Performance

Table 6 shows the average BST reading and math scores for first time test takers from various home languages. Students were separated out into groups by highest number of students in a group. “Other Languages” includes students from lesser represented language groups in the database: Afghan, Amharic/Tigrinia/Oromo, Arabic, Bosnian, Cambodian, Cebuano, Chinese, Croatian, French, Hindi, Lao Polish, Nuer, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish, Swahili, Ukranian, Vietnamese, and English dialects.

Table 6. Average Percent Correct by Home Language on First Tests

Language

|

|

Reading |

Math |

Hmong |

Mean

|

42.5% |

49.8% |

S.D. |

19.05 |

18.3 |

|

N |

104 |

103 |

|

Laotian |

Mean |

56.2% |

59.2% |

S.D. |

19.86 |

19.25 |

|

N. |

15 |

15 |

|

Spanish |

Mean |

51.6% |

56.5% |

S.D. |

18.75 |

19.62 |

|

N. |

115 |

116 |

|

Somali |

Mean |

42.3% |

39.2% |

S.D. |

14.73 |

14.91 |

|

N. |

26 |

25 |

|

Other |

Mean |

53.8% |

55.2% |

S.D. |

19.78 |

19.13 |

|

N. |

55 |

23 |

Across groups, students averaged about 49% correct on their first

reading test. Individual language group means for reading ranged from 42% to 56% correct.

On the first math test the total group averaged about 52% correct with individual language

groups ranging from 39% to 59% correct. It should be noted that within this sample are

students from a voluntary test year (1996) as well as students who may have been taking

the test for the first time in another year.

Multiple Time Test Takers and BST Performance

Table 7 shows the average mean scores for NELB (including LEP) students taking the BST reading and math tests the first time compared to the same students’ second or third time taking the tests.

Table 7. Average Gain in Scores of NELB Students from 1st to 2nd and 1st to 3rd Tests

|

Reading (n=186) |

Math (n=167) |

Reading (n=55) |

Math (n=47) |

||||

1st

Test |

2nd

Test |

1st

Test |

2nd

Test |

1st

Test |

3rd

Test |

1st

Test |

3rd

Test |

|

Mean

% Correct |

42.4% |

53.2% |

49.4% |

55.3% |

37.8% |

61.0% |

44.5% |

62.9% |

S.D. |

15.4 |

18.5 |

12.9 |

16.4 |

14.9 |

17.9 |

11.0 |

16.8 |

Test

Gains |

11

pts |

6

pts |

24

pts |

18

pts |

||||

*Note: Only a subset of students took the tests 3 times

As might be expected the gains between the 1st and 3rd test

attempts are greater than between the 1st and 2nd attempts. Gains ranged from 6 to 11

points from the 1st to 2nd test, compared to an 18 to 24 point gain from the 1st to 3rd

tests. Also, there was a higher average gain in reading than math. This may be explained

perhaps by more focused instruction and remediation in reading skills. Also, it may be

harder to teach students all the possible types of math problems that might appear,

including problems that require fairly sophisticated reading skills.

Re-testing by Home Language

Tables 8 and 9 show the BST performance of NELB (including LEP) students for the first and second test attempts by home language group on reading (Table 8) and math (Table 9). All groups showed increases in median test performance, except Somali students; this group had too few students to be reliable. Gains were largest for the Hmong and Spanish language groups. All groups showed increases on the second math test except for Spanish students; the scores of this group stayed the same. Again, the Somali group had too few students to be reliable.

Table 8. Median Percent Correct of NELB Students on First and Second Reading Tests

|

Home Language Groups of NELB Students

|

||||

|

Hmong (n=54)

|

Laotian (n=12)

|

Spanish (n=17)

|

Somali

(n=3) |

Other

(n=27,

26) |

|

Median |

Median |

Median |

Median |

Median |

1st

Test |

33% |

58% |

53% |

50% |

45% |

2nd

Test |

45% |

64% |

65% |

30% |

51% |

Table 9. Median Percent Correct of NELB Students on First and Second Math Tests

|

Home Language Groups of NELB Students

|

||||

|

Hmong (n=58)

|

Laotian (n=8)

|

Spanish (n=13)

|

Somali

(n=3) |

Other

(n=3) |

|

Median |

Median |

Median |

Median |

Median |

1st

Test |

43% |

54% |

54% |

28% |

50% |

2nd

Test |

54% |

60% |

54% |

31% |

62% |

Table 10 and 11 show the change in reading and math BST scores from the first attempt, grouped by percent correct, to the second attempt.

Table 10. Changes in Mean and Median Reading Scores from First to Second Tests

|

2nd

Test |

||

%

Correct on 1st Test |

N

in Group |

Mean

Gain for

Group in

% Pts |

Median

Gain for

Group in % Pts |

1-30% |

52 |

16.3

|

12.5

|

31-45% |

66 |

10.7

|

10.0

|

46-55% |

23 |

7.2 |

7.5 |

56-65% |

22 |

9.3 |

5.8 |

66-75% |

13 |

5.8 |

10.0

|

All

Groups |

176 |

11.3

|

10.0

|

Table 11. Changes in Mean and Median Math Scores from First to Second Tests

|

2nd

Test |

||

Percent

Correct on 1st Test |

N

in Group |

Mean

Gain for

Group in % Pts |

Median

Gain for

Group in % Pts |

1-30% |

13 |

8.1

|

0.0

|

31-45% |

50 |

8.5

|

8.8

|

46-55% |

35 |

3.5

|

2.9

|

56-65% |

34 |

4.7

|

7.4

|

66-75% |

21 |

3.1

|

4.1 |

All

Groups |

153 |

5.7

|

4.4 |

Overall, the average change in score from first to second time

testing in reading was 11.3 percentage points (median = 10). The median gain was largest

for the lowest scoring group (12.5 points), and the gains in the other groups were not all

that different. Of course, it is important that students with the lowest scores,

particularly below 30% correct, show larger gains because more gain is required to pass.

If the gains were to be constant on each additional test, then one might predict that

students in the lowest group would not pass prior to their anticipated graduation year.

However, the scores of individual students changed in different ways from the first to

second attempt. For example, when we looked at individual student data, we found one

student who had a score on the second test that was 35 percentage points lower than on the

first test. We also found at least one other student who had a score on the second test

that was 63 percentage points higher than on the first test.

The gains on the math test were not as great as on the reading

test. Overall, the average gain was less than 6 percentage points, and the median gain was

just over 4 points. The median gain was smallest in the lowest performing group (median

gain = 0), and largest in the group of students who scored between 31% and 45% correct on

the first test (median = 8.8). If this rate were to continue, one might predict that

students scoring below 55% correct on the first test would not pass by the anticipated

graduation year.

Table 12 shows the total number and percent of NELB students who passed the BSTs on their second attempt. Because of small numbers of students for whom these data are available we do not have good data to answer the question of how many NELB students from each language group passed the test after failing once. However, among the groups with more reliable information, 24% of Spanish students and 23% of “other languages” students passed the second reading test. Hmong students had the lowest percentage passing the second reading test, at 9%. For math, the highest percentages of those passing was “other languages” (17%) and Hmong (11%).

Table 12. Students Passing Reading and Math BSTs on the Second Attempt

|

N

Taking |

N

Passing |

%

Passing |

|

Hmong |

Reading |

54 |

5 |

9% |

Math |

58 |

6 |

11% |

|

Laotian |

Reading |

12 |

3 |

25% |

Math |

8 |

1 |

13% |

|

Spanish |

Reading |

17 |

4 |

24% |

Math |

13 |

1 |

8% |

|

Somali |

Reading |

3 |

1 |

33% |

Math |

3 |

0 |

0% |

|

Other |

Reading |

26 |

6 |

23% |

Math |

23 |

4 |

17% |

|

*

Percentages

have been rounded

ESL Bilingual Services and BST Performance

Table 13 shows the BST performance of NELB students who received ESL or bilingual services or did not receive services, during the year of testing. Students receiving services scored lower in reading and in math compared to those students not receiving services. This is not unexpected given the fact that students receiving services are learning the English language as well as content areas in school. Both students receiving services and those not receiving services scored slightly lower in reading than math across the years of testing.

Table 13. Median Percent Correct of NELB Students Receiving ESL Services

|

ESL

Services |

No

ESL Services |

|||

Median

% Correct |

Valid

N |

Median

% Correct |

Valid

N |

||

Reading |

1996 |

30% |

24 |

63% |

21 |

1997 |

40% |

44 |

64% |

28 |

|

1998 |

45% |

171 |

70% |

34 |

|

Math |

1996 |

41% |

24 |

65% |

23 |

1997 |

43% |

44 |

75% |

27 |

|

1998 |

49% |

173 |

76% |

37 |

|

Tables 14 and 15 show the percentages of NELB students passing the BSTs by whether they were receiving services. As reflected in the tables, students receiving services had lower numbers of students passing in reading and in math compared to students not receiving services. Among the students receiving services, the difference between the total numbers passing for reading and math was not great. For students not receiving services, the difference in numbers passing reading and math was also not great. However, for both groups the actual numbers of students passing the BSTs increased from 1996 to 1998.

Table 14. Reading Test Passing Rates of Students Receiving ESL Services

|

Pass |

Not

Pass |

|||

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

||

1996 |

Service

(n=24) |

0 |

0.0% |

24 |

100.0% |

No

Service (n=21) |

9 |

42.9% |

12 |

57.1% |

|

1997 |

Service

(n=44) |

0 |

0.0% |

44 |

100.0% |

No

Service (n=28) |

6 |

21.4% |

22 |

78.6% |

|

1998 |

Service

(n=171) |

20 |

11.7% |

151 |

88.3% |

No

Service (n=34) |

16 |

47.1% |

18 |

52.9% |

|

Table 15. Math Test Passing Rates of Students Receiving ESL Services

|

Pass |

Not

Pass |

|||

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

||

1996 |

Service

(n=24) |

1 |

4.2% |

23 |

95.8% |

No

Service (n=21) |

6 |

26.1% |

17 |

73.9% |

|

1997 |

Service

(n=44) |

1 |

2.3% |

43 |

97.7% |

No

Service (n=28) |

15 |

55.6% |

12 |

44.4% |

|

1998 |

Service

(n=171) |

27 |

15.6% |

146 |

84.4% |

No

Service (n=34) |

19 |

51.4% |

18 |

48.6% |

|

NRT and Language Proficiency Tests and BST Performance

The districts in the study used two different English language

proficiency tests. One used the LAS (Language Assessment Scale) oral proficiency measure

in combination with the reading test if the oral score was high enough. The other used the

Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery sub-tests. We found a relationship only between the

Broad English cluster (WBR) sub-test and the BSTs. Scores from the LAS oral test, Woodcock

Broad English cluster, and results from four Norm Referenced Tests (NRT) were correlated

to student performance on the BSTs. Scores from

four NRTs were combined to maximize the sample size. The most commonly used NRT was the

California Achievement Test (85%), followed by the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (14%). Only

NRT test scores occurring within two years of the BST administration were included in the

analysis. Also, almost all the proficiency tests included in this analysis sample were

administered within two years of BSTs. Keeping the sample to within two years of the BSTs

was to control for the effect of time between the proficiency and norm referenced tests

and the BSTs.

Correlations between scores on the BSTs and the language

proficiency measures are shown in Table 16. The Woodcock Broad English test had the

highest correlation with reading and math BST performance.

Table 16. Correlation Between Achievement on BSTs and Other Tests

Other

Tests

|

Reading

BST

|

Math

BST

|

||

Pearson

Correlation |

N

taking these tests |

Pearson

Correlation |

N

taking these tests |

|

LAS

Oral Test

|

0.561 |

90 |

0.419 |

93 |

Woodcock-

Broad English |

0.728 |

60 |

0.755 |

60 |

NRT

Reading |

0.652 |

212 |

0.598 |

210 |

NRT

Math |

0.377 |

184 |

0.485 |

182 |

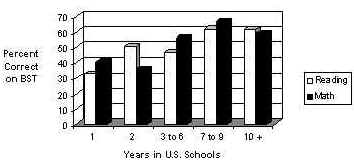

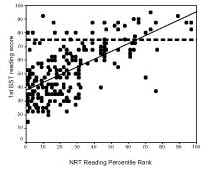

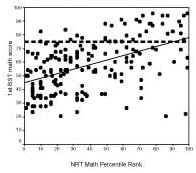

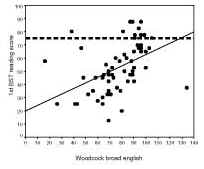

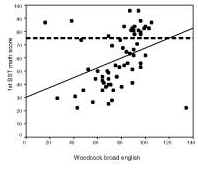

The relationships are represented graphically in Figures 3 to 6.

The WBR test correlated more strongly with both reading and math BSTs than did the other

two types of tests (LAS and NRTs). With the exception of a few outlying scores, there was

a strong relationship between WBR scores and BST scores.

Figure 3. WBR with BST Reading

Figure 4. WBR with BST Math

Figure 5. NRT with BST Reading

Figure 6. NRT with BST Math

NRT math scores did not correlate strongly with the Math BST.

Almost all students passing the BST math test scored above the 50th percentile on an NRT math test. However, students scoring above

the 70th percentile on an NRT math test were equally as likely to fail

the BST math test as to pass it. Therefore, there is no NRT score at or above which one

can be confident that the student will pass the BST math test. Although NRT reading

comprehension scores were moderately correlated with BST reading scores, the spread of

scores on the NRTs for students passing the BST was very broad (1st percentile to the 98th percentile). In order to be confident (above a 50/50 chance)

that a student will pass the BST reading test, the student must score above the 75th percentile on an NRT reading comprehension test.

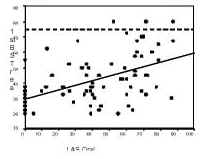

The LAS and BST Performance

Predicting whether a student will pass the BST based on recent

oral LAS scores is limited by two factors: (1) Most students in this sample for whom we

have LAS scores did not pass the BST. Only three students taking the LAS within three

years of the BST passed the reading test, and five passed the math test. (2) Students with

high scores (above 60) on the LAS were equally as likely to score poorly on the BST as

they were to pass the BST. Students with high LAS scores (above 60) were evenly

distributed between scores of 20 and 80 on the BST.

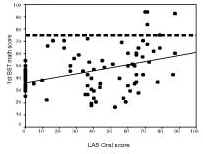

The relationship between LAS scores and BST scores are shown graphically in Figures 7 and 8. It is evident from these figures that the relationship between scores from the two types of measures is low.

Figure 7. LAS with BST Reading

Figure 8. LAS with BST Math

Woodcock Broad English Test and BST Performance

One cannot predict with any certainty from a particular WBR score

that a student will pass the BSTs. All but two students passing the reading BST the first

time scored above 80 on the WBR. However, nearly one-half of the students scoring above 80

on the WBR did not pass the BST. It is generally the same for math as for reading, as

shown in Figures 9 and 10.

Figure 9. WBR with BST Reading

Figure 10. WBR with BST Math

Research on LEP student participation and performance in

large-scale assessments tends to treat all LEP students as one group with the same needs

(Lucas, 1997). Also, research does not address the needs of specific groups of NELB

students who may be classified as LEP but who may or may not be receiving ESL services.

Examining the needs of specific subgroups is important for school improvement efforts that

incorporate test data. In-depth record reviews are a viable approach for schools to

undertake to better understand the educational needs of specific groups of students and to

address their needs through programs and instruction. However, school personnel must first

make concerted efforts to improve data collection and data keeping. This study highlights

the issues educators and researchers need to consider when using data found in school

records.

Students in our record review sample were predominantly those in

grades 8, 9 and 10, most of whom received free or reduced lunch supports, those who

primarily have moved fewer than three times after coming to the U.S., and who have a

variety of home languages, but particularly Hmong and Spanish. The data are not limited to

students who have been in a district a certain number of years. Similarly, they are not

limited to students who have been in the U.S. or in U.S. schools a specific number of

years.

Findings from this study that may have implications for NELB and

LEP students in general fall into three areas. First, there is a fairly strong negative

correlation between the number of school changes and BST performance. It is possible that

there may be a general negative correlation between school changes and test scores

(Kerbow, 1996) or number of absences (Cota, 1997). Extra instructional efforts may need to

be directed toward those students who have frequently changed schools, especially those

with more than three school changes. It is possible that these students are missing out on

test taking strategies as well as content, so both might need to be a focus of

instruction. We acknowledge the difficulty of targeting these extra instructional efforts

to a population that may not remain in one place for very long, and recommend future study

in the area of best practices in assessment preparation for these students.

Second, there was a strong correlation between years in U.S.

schools and BST performance. Thus, the performance of LEP students does improve with

increased time in the U.S. Students’ improved performance with more language

instruction was also shown in a California study (Cota, 1997).

Third, there are interesting relationships between language

proficiency measures and BST performance. We found that initial performance on language

proficiency tests, which are typically given to new students for evaluation purposes and

ESL placement, did not correlate with later performance on the BSTs. In fact, we found

that virtually all students who were given a language proficiency test within three years

of taking the BST did NOT pass the BST during the years of the study. One plausible

conclusion would be that LEP students who have had ESL/bilingual services fewer than three

years are going to need more than three years to pass the BSTs.

While data for one of the districts indicated that about half of

the students who earned a score above 55% correct on their first BST reading passed the

second time they took the test, no such relationship was found for math for the students

in this study. And, the relationship for reading is not strong. Students who performed

among the lowest the first time tested sometimes passed the second time. And, not all

students who scored very close to passing the first time tested passed the second time.

These data suggest that it is probably an unwise strategy to focus instructional efforts

more on those whose scores appeared to be closest to passing. Rather, devoting efforts

equally remains the best strategy for improving performance. However, these results are

from a district level analysis. Examination of performance from first to subsequent

attempts for statewide BST takers may be different.

Addressing the differences among language groups in our study is

limited by incomplete data. For this reason, many analyses do not allow us to say much

about Somali and Laotian speaking students even though the actual numbers of students

enrolled in study sites may be larger than represented here. There were few large

differences among groups in performance, either for first time testing or for re-testing,

when the Somali and Laotian language groups were not considered.

Of the more significant outcomes of this study is a recognition

of the importance of clear, organized, data management for LEP students. It is often

assumed that students’ information is complete and accessible within schools or

districts, but this is not always the case. A problem in the course of this study clearly

was the lack of data. Collecting information for this study required a combination of

sources, which still resulted in gaps of information, and in some cases conflicting

information. A better record keeping system at the school level in cooperation with

district data management seems to be an essential step toward better understanding the

needs of LEP students and possible ways to address them.

August, D., Hakuta, K., Olguin, F., & Pompa, D. (1995).

Evaluating the inclusion of LEP students in systemic reform. In Issues and strategies in evaluating systemic reform. Papers

prepared for the U.S. Department of Education, Office of the Under Secretary, Planning and

Evaluation Service.

Cota, I. (1997). The role of previous educational learning

experiences on current academic performance and second language proficiency of

intermediate school limited English proficient students. Bilingual Research Journal, 21:2 & 3, Spring

and Summer.

Kerbow, D. (1996). Patterns

of urban student mobility and local school reform: A technical report [On-line].

CRESPAR, Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed at Risk: Report # 5.

Program 7 Systemic and Policy-Related Studies, Johns Hopkins University and Howard

University. Available: http://www.csos.jhu.edu/crespar/Reports/report05entire.html.

Liu, K., Thurlow, M., Thompson, S., & Albus, D. (1999). Participation and performance of students from

non-English language backgrounds: Minnesota’s 1996 Basic Standards Tests in reading

and math. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational

Outcomes.

Liu, K., & Thurlow, M. (2000) Linking student and programmatic characteristics to

test performance: Issues & solutions. Manuscript in preparation.

Lucas, T. (1997). Into,

through and beyond secondary school: Critical transitions for immigrant youths.

McHenry, IL: Delta Systems, Co., Inc.

National Center for Education Statistics. (1996). Proceedings of the conference on inclusion

guidelines and accommodations for LEP students in the NAEP: December 5-6 1994 (NCES

96-86[1]). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research

and Improvement.