Prepared by Kristin Liu, Michael E. Anderson, Bonnie Swierzbin and Martha Thurlow

This document has been archived by NCEO because some of the information it contains is out of date.

Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Liu, K., Anderson, M. E., Swierzbin, B., & Thurlow, M. (1999). Bilingual accommodations for limited English proficient students on statewide reading tests: Phase 1 (Minnesota Report No. 20). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/MnReport20.html

As more and more states implement high stakes assessments that include students with limited English proficiency (LEP students), it is becoming clear that a significant number of LEP students are having difficulty passing such tests (Liu & Thurlow, 1999; Liu, Thurlow, Thompson, & Albus, 1999). The negative impact on LEP students’ future educational attainment and work prospects may be severe if they cannot graduate from high school and obtain a diploma (Boesel, Alsalam, & Smith, 1998; Coley, 1995; Hodgkinson & Outtz, 1992).

While it is reasonable to expect that LEP students be offered the same opportunity to learn test content as their native-English speaking peers, tests can confront LEP students with language challenges that can make it difficult for them to demonstrate their content understanding. The use of unfamiliar vocabulary in a test item, for example, can make it difficult for LEP students to answer the item, even if they are capable of performing the task that is asked of them. Recent examples from the sample Minnesota Basic Standards Tests (BSTs) (http://cfl.state.mn.us/GRAD/pdffiles.htm), exams that a student must pass by 12th grade in order to receive a diploma, illustrate the problem:

Example from the reading BST:

According to the author, which of the following is "authentic" to New Mexico food?

a. deep-fried foods

b. lots of cheese

c. sour cream

d. green chiles

Example from the mathematics BST:

You have two tickets to the school raffle. There are 600 tickets altogether in the raffle. If one ticket is drawn, what is the probability that it will be one of your tickets?

a. one out of 600

b. two out of 600

c. two out of six

d. 600 out of two

In the first example above of a literal comprehension question, if a student does not understand the word "authentic," and the word is not used in this context in the reading passage, it is difficult to understand what is being asked in the question. In the second example, there is no reading passage to offer context for guessing the meaning of the term "raffle." Not knowing this word could significantly distract a student from the mathematical task being asked. Clearly, a student who is in the process of learning English is at a disadvantage when confronted with items like these in which English vocabulary knowledge is being tested along with reading and math skills.

Accommodations or modifications that reduce the English language load for LEP students would help the students to more accurately perform the tasks required of them on standardized tests. However, to date, there is little research available showing the effects of accommodations or modifications on LEP students’ standardized test scores, particularly for accommodations offered in the students’ dominant language. The work of researchers at the Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST) provides the most thorough quantitative analysis of the impact of test accommodations such as simplified English and dictionaries on scores for LEP and regular education students taking the National Assessment of Educational Progress. However, the NAEP data do not address the desirability of various testing accommodations and modifications for LEP students. Do LEP students and their families view test accommodations positively? If offered, would LEP students choose to use a particular accommodation on a large-scale assessment?

The purpose of this report is to share the initial results from a quantitative and qualitative study examining the feasibility and desirability of offering LEP students a reading test with bilingual test items and answer choices.

Demographic figures show that the LEP student population in Minnesota, as in many other states, is growing (Tarone, 1999). As this population increases, so does the need to find more meaningful ways in which to include LEP students at all proficiency levels in the statewide accountability system. Including these students would help to ensure that the academic needs of all students are being met and that all students will progress toward the ultimate goal of graduation. In order for system accountability to work, it must include all students. Not including LEP students in statewide accountability systems can have a negative impact on the students’ learning by lowering the expectations for these students and leaving the school programs for these students unaccountable for their progress (LaCelle-Peterson & Rivera, 1994; Rivera & Stansfield, 1998; Saville-Troike, 1991; Zlatos, 1994).

The state of Minnesota, like many other states, is in the process of implementing a statewide accountability system that includes standardized testing as a major component. In this system, students must pass Basic Standards Tests (BSTs) in reading, mathematics, and writing in order to receive a high school diploma. Figures from 1996-98, the first three years of testing, show that math and reading participation rates for LEP students who were first-time test takers ranged from 66 to 100 percent. Excluding 1996, a year in which participation was optional, the participation rates for LEP students ranged from 88 to 100 percent (Liu & Thurlow, 1999). It is clear that test participation rates for LEP students are relatively high in Minnesota.

For students taking the tests in reading and mathematics for the first time, however, the passing rates of LEP students receiving ESL services are far lower than those of the general population (Liu & Thurlow, 1999). Language is one obvious reason for this difference in scores. As LEP students make the transition into the English language school system, standardized tests become as much a test of English language skills as a test of academic content skills. It has been shown that students’ language proficiency can adversely affect their performance on standardized tests administered in English (Abedi, Lord, & Plummer, 1997). Furthermore, using standardized tests that have been normed only for a monolingual English population leaves questions as to the validity of these tests for LEP students (LaCelle-Peterson & Rivera, 1994). How then do educators include LEP students in the statewide accountability testing process, yet ensure that the tests are valid measures of the students’ reading or math skills and not merely tests of their English abilities?

One way to do this is through the use of testing accommodations or modifications that make the test more accessible to students. In Basic Standards testing, a modification, which is an adjustment that alters the standard being tested, is differentiated from an accommodation, which is an adjustment in the testing conditions that does not alter the standard. While accommodations and modifications to the Minnesota Basic Standards tests are permitted, those available might not address the real problems that LEP students have in accessing a test. (See Table 1 for accommodations and modifications permitted for LEP students taking the Minnesota BSTs.)

In general, many of the accommodations and modifications available to LEP students on large-scale tests have been developed with students with disabilities in mind. This is not uncommon, since LEP students do not have the same legislative support for accommodations as do students with disabilities. Common accommodations such as setting and presentation changes (e.g., small group administrations or short segment test booklets) may not be as effective for LEP students whose real hurdle in performing to the best of their abilities is the language barrier (Rivera & Vincent, 1997).

In 1997, a year for which data on the use of test accommodations are available, the overall passing rate on the BST reading test for LEP eighth graders receiving ESL services was 8%, compared to 2% for just those LEP students taking the test with accommodations. In contrast, the overall passing rate on the BST math test for LEP eighth graders receiving ESL services was 21%, compared to 83% for only those LEP students taking the math test with accommodations (Liu & Thurlow, 1999). Because the state did not collect data on the specific accommodation or combination of accommodations used by each student, it is difficult to account for the extreme difference in passing rates between the reading and math tests. It is also unclear who made the decisions about accommodations that were provided and how this decision-making process varied from district to district. There is one clear difference in the accommodations offered. The math test can be translated into a student’s first language, while the reading test cannot.

Table1. Accommodations and Modifications Permitted for LEP Students Taking the Minnesota Basic Standards Tests (1998-99 school year)

| Accommodations | Modifications |

|

Oral interpretations (math and written composition only) |

To date, there is little research on the effectiveness of providing native language accommodations for LEP students on statewide assessments, especially when the test is a reading assessment. If native language accommodations are offered in high-stakes testing, they are often not allowed for tests of reading ability. For some LEP students, a reading test is often a test of vocabulary knowledge as much as it is a test of reading ability. A reading test assesses not only a student’s ability to comprehend the test passages, but also a student’s ability to comprehend the test questions, recognize paraphrases and make inferences as well as testing the breadth of the student’s vocabulary and world knowledge. If we are only trying to test comprehension of a reading passage, the format and language of the questions should not matter as long as they do not affect the validity of the test.

In providing a language accommodation for a test, educators must also consider whether the accommodation will be useful for the student. If the accommodation does not fit within the curriculum, it may not be of much help. For example, Abedi, Lord, and Hofstetter (1998) found that translating math tests into the native language of LEP students was not always helpful if math instruction took place in English. In a related study of accommodations for the NAEP math test, however, it was found that simplifying the English of the test questions produced higher scores for LEP students (Abedi, Lord, & Plummer, 1997). Higher scores do not tell the whole story. In order to find out whether the accommodations are being used by the students, students need to be asked whether they are using the accommodations and if so, how they are using them. Monitoring the use of an accommodation is of the utmost importance, not only to assure the validity of the test, but also to ensure that the expense and effort of providing the accommodation are worthwhile. In considering the use of a native language translation accommodation to the Minnesota Basic Standards reading test questions, the following factors were considered.

• Translation Use Issues. Little research is available on the use of bilingual translations, especially with reading tests. Stansfield (1997) conducted an informal survey of translation use and found that several programs and testing agencies use side-by-side translations. Other testing agencies have the examinee choose the preferred form of the test or take the test in both languages and record the higher of the two scores. Stansfield and Kahl (1998) pointed out that additional time might be needed for students taking a bilingual exam because there is more text to read and process. In addition, they found that educators and students perceived a bilingual test booklet more positively than a Spanish-only translation of a math test. In a NAEP study using bilingual (English-Spanish) test booklets with a math test, students were asked to mark their answer on just one version of each test question (English or Spanish). Most students in grade eight answered only the Spanish version of the test questions. Some students did answer questions in both versions, although it is unclear to what extent they actually used both versions (Anderson, Jenkins, & Miller, 1995). In the study described in this report, students were given both the English and the Spanish translation so that they could use either one or a combination of the two. Students were then asked to indicate which version(s) of the test questions was used.

• Idiomatic English. Expressing concern about problems LEP students had with idiomatic speech in the BST reading test (e.g., "break a leg" used to mean "good luck"), ESL and bilingual educators in the state of Minnesota indicated that the use of some sort of bilingual dictionary might be an appropriate accommodation for the BSTs (Liu, Spicuzza, Erickson, Thurlow, & Ruhland, 1997). In a study focusing on Hispanic students taking reading tests, Garcia (1991) found that lack of vocabulary seemed to be the major linguistic difficulty students had with the reading exam. Garcia’s study also showed that standard reading tests in English can underestimate an LEP student’s reading ability. In this study we offered students the test questions in English and in their native language so students could check for the translation of difficult English words.

• First Language Literacy. In focus groups, parents of LEP students in Minnesota and students themselves expressed support for learning English, but were concerned with the difficulty level of the tests for students in the process of acquiring academic English language skills. Focus groups pointed out that written translations would not be useful to students who were not literate in their first language (Quest, Liu, & Thurlow, 1997). For this reason, it was decided to test the use of the bilingual reading test with the questions and directions provided aurally in Spanish as well as written in Spanish and English. The translated version of the Basic Standards math test is also presented in both written and aural forms.

• Social Factors. Studies indicate that accommodations that make the LEP student appear "different" from other students might not be helpful because students would not use them (Liu, Spicuzza, & Erickson, 1996). Furthermore, students were concerned with the effects of passing at a modified level that would be indicated on their diploma as "Pass-Translate" (Quest et al., 1997). Taking the actual use of accommodations into account, a survey and student interviews were incorporated into different stages of this study to account for whether the students used the accommodations available to them and, if so, how they used them.

• Translation Issues. Creating an equivalent translation of any text can be a problematic, time consuming, and costly process. According to translation guidelines by The International Test Commission (Van de Vijver & Hambleton, 1996), the effects of cultural differences between the group for which the test was written and the group for which it is being translated should be minimized. Evidence should be provided to show that language in the directions and items is appropriate for the cultural group for whom the translation is intended. In addition, linguistic and statistical evidence should be used to assess the equivalence of the two language versions of the test. The test used in this study was developed with the assistance of a native Spanish-speaker (with a college degree from a Spanish-speaking University, thus fluent in academic Spanish) who was a member of the cultural group that the students came from and a fluent speaker of English. The translator reviewed reading passages for cultural relevance prior to translation. To verify the accuracy of the translation, a second native speaker of Spanish reviewed translated passages. Passages were then field tested on a group of nine Spanish-speaking students, as described further in this paper.

Taking all of the information surrounding the use of the native language into account, a study was designed to examine the use and usefulness of test questions presented in a bilingual format after reading a passage in English. For this study, we will refer to the bilingual translation being studied as an accommodation since the results are not yet conclusive as to whether it alters the standard being tested. The two-part study uses both qualitative and quantitative methods and was conducted in two phases. Phase 1 had two main purposes: (1) to verify that the translations and the format of the test were comprehensible to students, and (2) to find out how the students used the translated test items. Phase 1 was conducted with a small group of students so that each student could be interviewed about the test accommodations. The results of Phase 1 are reported here. Phase 2 of the study, which will be discussed in a subsequent report, used the test scores of a much larger group of students to evaluate the equivalence of the original and translated versions of the test.

Instrument

The instrument used for this study was a reading test developed by personnel at the Minnesota Department of Children, Families and Learning to approximate a version of the Minnesota Basic Standards reading test. The reading passages were all taken from newspaper feature articles. The reading passages and questions were originally developed for use in the actual Basic Standards Test of reading, but were not used. The testing team (an ESL specialist, test specialists, and a bilingual translator) modified the passages and the questions to be as close as possible to items that would actually be used in the statewide test. The test consisted of five reading passages with ten comprehension questions about each passage. Both literal and inferential comprehension questions were included. The test questions, or items, were then translated into Spanish and formatted in a side-by-side fashion with the original English language form of the questions.

With the translation guidelines of the International Test Commission (Van de Vijver & Hambleton, 1996) in mind, the testing team used the following process to translate the test questions. First, the test was reviewed for cultural bias. A bilingual translator then translated the test questions into Spanish. The questions were translated back to English (a "back translation") by another bilingual translator and compared to the original English questions. Relatively few differences were found. A member of the testing team and the original translator reconciled changes to the Spanish version of the questions. Changes to the translations based on the back translation were made after the first phase of the study and input from the retrospective student interviews was also taken into account. The changes made were relatively minor.

While the reading passages were only presented in English, the test questions were presented side-by-side in English and Spanish. The participants also were able to listen to the test directions and test questions read aloud in Spanish on an audiocassette. Each participant had a tape player with headphones with which to listen to the audio tape if desired. Each student controlled his or her tape player and was able to listen or re-listen to the items on the tape as needed. The study included both written and tape-recorded translations since that is the format in which the accommodation package would be offered by the state if this accommodation were allowed. The student taking the test could decide what version(s) of the translation to use, if any.

The test was not timed, but there were only about two hours available for each testing session. Thus, some students were not able to complete both passages and be interviewed after each one. Each student did complete at least one reading passage and was interviewed about it. Completing both passages was not important for this phase of the study, since the main focus was to gain information about the students’ impressions of the accommodations. Students were instructed to take as much time as they needed to complete each passage.

Participants

The participants in Phase 1 included nine seventh graders at one middle school. The school faculty identified all of the participants as being in ESL/bilingual classes and having Spanish as their first spoken language. All of the participants spoke the same dialect of Mexican Spanish. Six of the participants were male and three were female. Seven of the nine students were listed as qualifying for free lunch in the state database. Socioeconomic indicators for the remaining two students were not available.

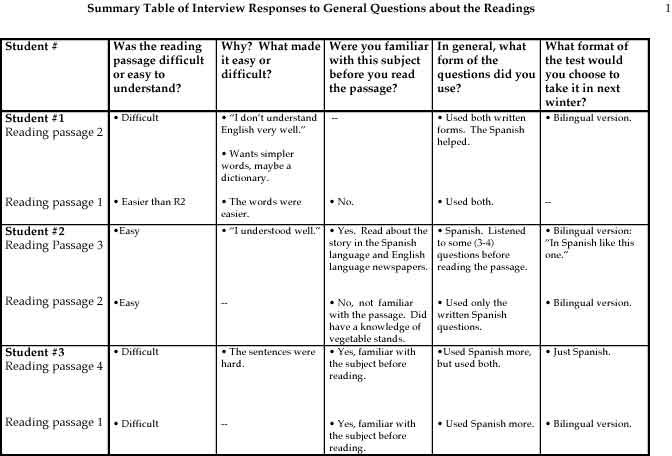

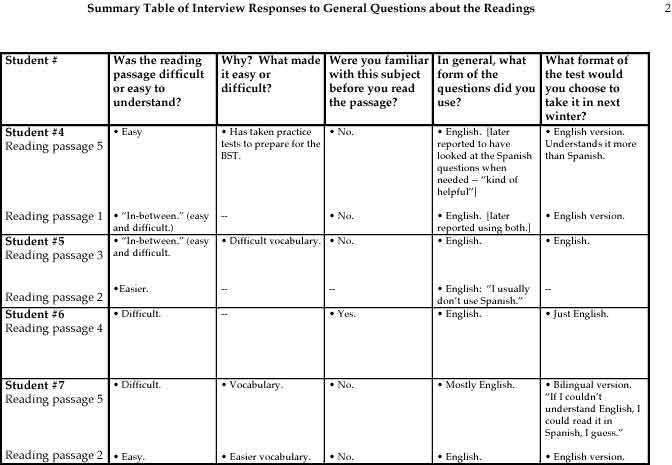

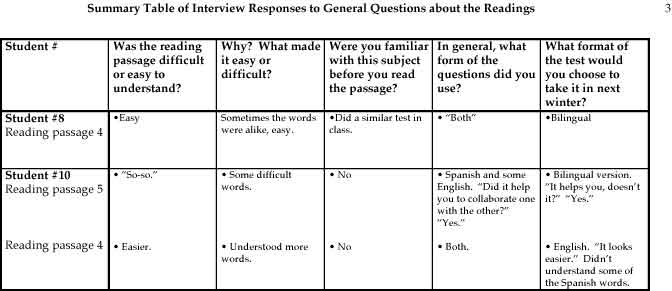

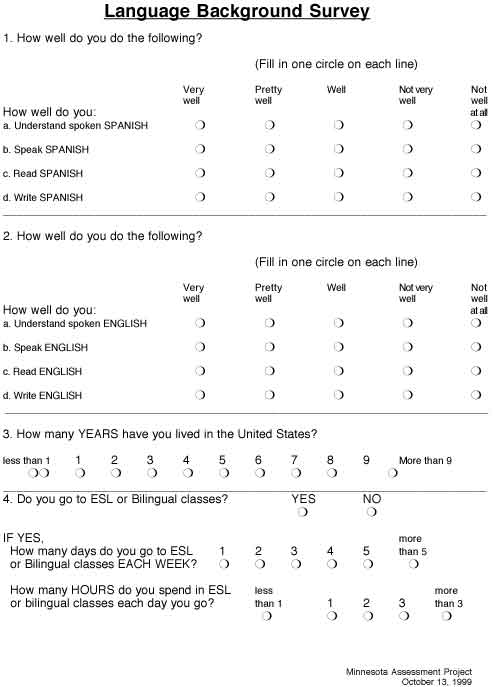

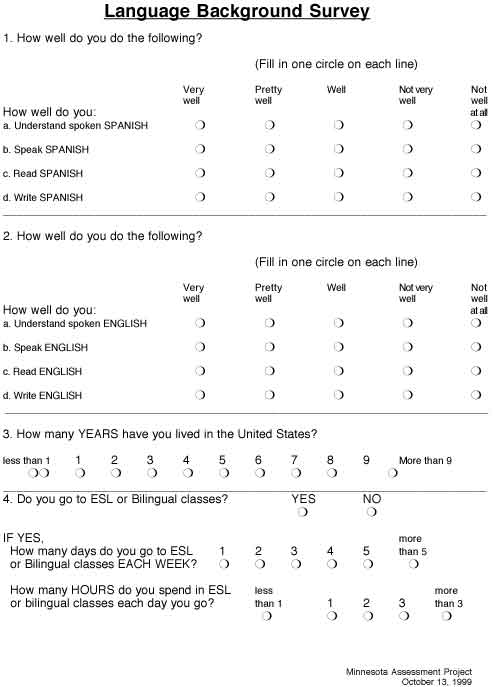

The school faculty selected the students who participated in the study based on a request for a group of students with diverse reading abilities in Spanish and English. A bilingual interpreter administered the test to each student on an individual basis. There were no more than two students in any testing room. Each participant was asked to complete one or two of the five passages of the test (depending on time considerations) and answer the questions presented in the bilingual format. Upon completion of each set of ten questions, the student was interviewed about the test by the bilingual interviewer. Interview questions addressed the general use of the accommodations and student perceptions of each item of the test (see Appendix A). The retrospective interviews were taped and transcribed (and translated if conducted in Spanish). Students were also asked to complete a demographic survey (see Appendix B). Information from the demographic survey, test scores, and the interviews were analyzed using software for analyzing qualitative data (Non-numerical Unstructured Data by Indexing Searching and Theorizing—NUD*IST).

Overall, students scored below a passing rate of 75% correct or above on the test (see Table 2). Only one of the students scored above the passing rate on any of the reading passages. There were a fairly wide range of scores on each of the passages, indicating a wide range of ability levels among the participants.

Verification of the Test Format

The first purpose of Phase 1 was to try out the format of the test in order to see whether students would have problems using the accommodation. None of the students reported having problems understanding the structure of the test or the type of Spanish used in the translation. The side-by-side format was not confusing and those who used the tape-recorded questions did not report having problems using the accommodation.

Table 2. Scores for Participants in Phase 1

ID # |

Passage | Score | Passage | Score | Comments |

| 1 | 1 | 4/10 | 2 | 4/10 | Didn't complete test # 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 2/10 | 3 | 5/10 | |

| 3 | 1 | 4/10 | 4 | 6/10 | |

| 4 | 1 | 5/10 | 5 | 4/10 | |

| 5 | 1 | 4/10 | 3 | 1/10 | |

| 6 | 4 | 6/10 | Only completed one passage | ||

| 7 | 2 | 6/10 | 5 | 3/10 | |

| 8 | 4 | 10/10 | Only completed one passage | ||

| 9 | Student 9 was absent the day of the test | ||||

| 10 | 4 | 1/10 | 5 | 3/10 |

In general, the students did not report using the taped version of the test questions. One student listened to some of the questions before reading them, while others did not use the tape player at all. This makes it difficult to determine whether the questions read aloud on the tape would have helped these students. What is clear is that they chose not to use this part of the accommodation. Students were not asked specifically why they did not use the tape player. Some students may have felt pressure not to use it even if there was only one other student in the room, and some may not have thought it would be helpful. More self-report data will be collected on accommodation use in Phase 2 of this study.

The table in Appendix C displays student answers to interview questions that asked about the difficulty of the test and about accommodation use. When students were asked whether the reading passages were difficult or easy to understand, answers were split. For example, one student found the first reading passage difficult, one found it easy, and another found it "so-so." This split tended to occur in every group of students who read a passage. For those students who thought a particular passage was difficult, the majority of them referred to the difficult vocabulary in their explanation. One referred to his or her lack of ability to understand English and one mentioned difficult sentences. Contrary to what the researchers expected, the students who reported that a reading passage was difficult often said that they were familiar with the topic of the reading prior to beginning the test. In contrast, the students who indicated that a particular passage was easy often said that they had no familiarity with the topic prior to reading. Without looking at the students’ test results, these findings indicate that factors other than a lack of background knowledge might be impacting LEP students’ reading test scores. However, answers may also indicate that some students are not necessarily expressing candid opinions to researchers. Students may have felt pressure to answer in a particular way because they were interacting with an unfamiliar researcher. It should be noted that students’ rating of the difficulty of the second passage that they read often was a comparison of the second passage to the first. That is, when asked, "Was this passage easy or difficult?" the student often said something like, "Easier than the first one."

Use of the Bilingual Accommodations

As mentioned above, none of the students used the taped version of the Spanish questions to any great extent. Four of the nine students reported using the written English version of the test more than the written Spanish version, although two of these students indicated that they did use the written Spanish version. Five of the nine students reported using both versions of the written questions. Two of these students reported that they used mainly the Spanish versions of the questions. It is clear that the use of the accommodation varied greatly depending on the student and what he or she was more comfortable using. Some students reported that their use of the accommodation varied depending on the passage that they were reading. For passages that were found to be easy to read, they did not use the questions written in Spanish as much as they did for passages that they considered to be more difficult.

All of the students were asked, after each reading passage, which format they would prefer to take the Basic Standards reading test in (English-only or the bilingual version) if given the option (Appendix A). The answers to this question varied by student. Six of the nine students reported preferring the bilingual version of the test for at least one of the two passages they completed. Three of the students in the study reported wanting only the English version of the test if given the choice. These students were also the students who had been in the country the longest (8 or more years). Only one other student reported being in the USA more than 9 years. She reported preferring the bilingual format after the first passage she read and an English only format after completing a second passage because it was perceived to be easier.

It is not surprising that the students who had the most exposure to the English language, as measured by their time in the USA, were the students who did not think they needed the test questions in Spanish. It is interesting that some students, given the choice of native-language accommodations, reported that they would choose not to use them. This may be due to a desire to meet the same standard as everyone else, English becoming the more dominant of their two languages, or perhaps a reflection of English being the primary language of instruction in school. These students did not report their reading abilities in English to be much stronger than their reading abilities in Spanish. When asked why they would prefer the English-only version of the test, two of the students responded, "I usually don’t use Spanish" and "English, cause I understand it more than Spanish."

At the other end of the spectrum, one student reported using almost exclusively the Spanish form of the test questions. For the most part students reported using one form of the questions (usually English) and referring to the other form when they did not understand something or to confirm their understanding of what was being asked. For example:

Interviewer: Okay. Why? What would make you want to have both English and Spanish?

Student #07: Well, if I don’t understand English, I could read it in Spanish, I guess.

Interviewer: Okay.

Student #07: I could understand it better.

Interviewer: Okay, so to clarify or to check what you understood, you would use the Spanish?

Student #07: Yeah.

Translation of interview conducted in Spanish:

Interviewer: Did you use Spanish or English?

Student #10: Spanish and some in English.

Interviewer: Did it help you to collaborate one with the other?

Student #10: Uh huh [meaning yes].

Interviewer: It was like your dictionary.

Student #10: Yes.

None of the students mentioned reading all of the questions in both languages.

Were the Translations Helpful?

While it is important to find out whether students used the accommodation, it is equally important to examine how they used the accommodation and whether it was helpful. In general, the students taking the reading test found the test to be challenging. As mentioned above, of the sections of the test that students had time to complete, only one student completed a passage at a passing level (75% or above). It should be noted that the actual Basic Standards reading test contains four passages and 40 questions, whereas during Phase 1 students only completed one or two reading passages with ten questions each. The limited number of questions used in this phase of the study might not be enough to test the breadth of the students’ abilities. Phase 2 of this study will examine student scores on the full test more closely.

Difficult vocabulary was a theme that was mentioned by many students in the study. Vocabulary found to be difficult included both vocabulary specific to the reading passage and vocabulary unique to the comprehension questions (e.g., "fact" vs. "opinion"). This seemed to be the greatest obstacle to understanding the test questions. Vocabulary items cited as being particularly difficult were specialized words such as "mechanized transport" or "accommodations" as well as proper nouns such as "Bethlehem" and "Connecticut." Other words in English cited as being difficult included "processed," "government," "related," "produce" (noun), and "anthropology."

For some of the difficult vocabulary items, some students were not familiar with the word in English or in Spanish. In these cases, the translation did not help the student’s understanding because it did not provide additional information about the word that the student could use. Some of these words had cognates in Spanish such as "opinion-opinión" and "article-artículo." In situations such as this, when students went to the Spanish translation, they found it to be of no help. The translation did not act as a dictionary, because it did not provide the students with information about the meaning of the word. In these cases a dictionary or a glossary might have been more helpful. The exchange in the following excerpt from an interview illustrates some of this frustration:

Interviewer: So, you went to and you read the Spanish question and then did you understand the Spanish? Or was that helpful, or...

Student #04: That was kind of, kind of...

Interviewer: Kind of.

Student #04: Helpful.

Later in this interview, after reading a second passage, the same student indicates that she did not understand the word ‘produce’ (used as a noun in the text.) The interviewer then asks her about the test question concerning this vocabulary item:

Interviewer: So did you, which version did you read like, English or Spanish?

Student #04: Both.

Interviewer: Both. Were there words you didn’t understand?

Student #04: No.

Interviewer: What about "produce"?

Student #04: "Produce"?

Interviewer: Uh. In Spanish, "productos"? No? You have produce in Spanish.

Student #04: (unclear)

Interviewer: OK. So that was a hard word in that question?

Student #04: Kinda.

Interviewer: Kinda? OK. And why did you choose answer A?

Student #04: ’Cause I guessed.

In this case, the student used both the English and Spanish versions of the written questions, but because she did not know the meaning of the term in either language she did not benefit from the accommodation and ended up guessing.

In some cases, the vocabulary that was difficult for the student to understand was crucial to answering the question. An understanding of this vocabulary is what the test was designed to measure. An example of this is the difference in meaning between a "fact" and an "opinion." More than one student reported having difficulty understanding these words in questions such as, "Which of the following is an opinion, not a fact, from this article?" In this case, the direct translation did not give the students additional information about the meaning of these words. However, defining these words in the form of a glossary or a dictionary might be considered to compromise the validity of the test. The students who did not understand the difference in this case would need instruction on the distinction between a fact and an opinion.

Care should be taken when applying the results of this study with Spanish-speaking students to LEP students from other language groups. Students in other language groups bring different cultural attitudes and beliefs to a testing situation; these attitudes and beliefs may make the use of accommodations more or less desirable than they were for the Spanish-speaking students. In addition, students from language groups that do not share cognates with English may find the helpfulness of bilingual test items and answer choices to be different as well. Although Spanish-speaking students do not represent the largest ethnic population of LEP students in Minnesota, a Spanish-English version of the reading test was used in this study because Spanish-speaking students share a common (albeit dialectally diverse) first language. The largest population of LEP students in Minnesota is Hmong. Although these students share a common ethnic heritage, their first language varies depending on where they lived before they arrived in the United States and choosing a single language in which to conduct a field test is problematic. This is an issue that would need to be addressed if the accommodations examined in this study were adopted by the state. Districts would then need to provide the accommodation to all LEP students who requested it.

With these cautions in mind, the following general recommendations are made:

• Make accommodation decisions on an individual student basis. In this study, some students used a combination of the English-only test and the native language translation while some students used only the English version. Most students used only the written translation while one or two used the translation on audio tape. Clearly if one accommodation decision had been made to cover all of the LEP students involved in this study, it would not have met the needs of the individual students.

• Obtain LEP student and parent input when making accommodations decisions in high-stakes testing. Students and their families know the most about whether a particular accommodation is appropriate based on: (1) whether the student is literate in the native language, (2) what level of reading proficiency and aural proficiency the student has in both English and the native language, and (3) what accommodations, if any, are acceptable to the student and what the student will agree to use in a testing situation that includes peers. Social pressures might encourage students not to use an accommodation and LEP students who wish to use an accommodation may need to be tested in an individual setting.

• Investigate the use of dictionaries or word lists in the students’ native language and English. Students in this study appear to have been using the translated version as a kind of dictionary to find the meanings of words that they did not know.

• Consider whether technology is widely available before offering accommodations that involve tape recorders or other machines. In this study, several schools did not have enough tape recorders or head phones to offer one to every student. Tape recorders that were available often had poor quality and the poor sound may have affected the students’ ability to benefit from the accommodation.

• Weigh the costs of providing a high quality translation in different languages. In this study, great care and expense went into providing a clear and accurate translation in the students’ native language, but few students actually used the translation. However, the study reported here involved students who were several years away from having poor test performance result in negative consequences. Further investigation into the use of translations by students who have failed a high stakes test multiple times and are in their final year of high school might show different results.

Due to time and resource limitations, not all of the steps recommended for verifying a translation were feasible for this study, but steps were taken to ensure an accurate and usable translation. The process of decentering (Van de Vijver & Hambleton, 1996), for example, is not feasible in this case because it is not possible to alter the English version of the test once it has been created to fit each bilingual translation. There can only be one English version of the test.

Phase 2

Despite the cautions and issues that have been identified, Phase 1 results supported the continuation of research on the effects of bilingual reading test items. A major goal of Phase 2 is to see whether the bilingual test questions affect the performance of LEP students. This will involve administering the complete reading test to larger groups of students. The test will be administered to a group of LEP students with the bilingual accommodations. Another group of LEP students will be given the unaccommodated version of the test. Finally, a group of general education students will be administered the unaccommodated version of the test as a control.

The students taking the accommodated version of the test will fill out a questionnaire about their use of the accommodations offered. It is hoped that these data, combined with the information already gathered in Phase 1 will provide useful insight into the use and usefulness of providing bilingual reading accommodations on statewide tests.

References

Abedi, J., Lord, C., & Hofstetter, C. (1998). Impact of selected background variables on students’ NAEP math performance (CSE Technical Report 478). Los Angeles, CA: UCLA, National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards and Student Testing.

Abedi, J., Lord, C., & Plummer, J. (1997). Final report of language background as a variable in NAEP mathematics performance (CSE Technical Report 429). Los Angeles, CA: UCLA, National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards and Student Testing.

Anderson, N., Jenkins, F., & Miller, K. (1995). NAEP inclusion criteria and testing accommodations: Findings from the NAEP 1995 field test in mathematics. New Jersey: Educational Testing Service.

Boesel, D., Alsalam, N., & Smith, T. (1998, February). Educational and labor market performance of GED recipients. Washington, DC: National Library of Education, Office of Research and Improvement, U.S. Department of Education. http://www.ed.gov/pubs/GED/

Coley, R. (1995). Dreams deferred: High school dropouts in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service Policy Information Center.

Garcia, G. E. (1991). Factors influencing the English reading test performance of Spanish-speaking Hispanic children. Reading Research Quarterly, 26 (4), 371-392.

Hodgkinson, H., & Outtz, J. (1992). The nation and the states: A profile and data book of America’s diversity. Washington DC: Institute for Educational Leadership, Center for Demographic Policy.

LaCelle-Peterson, M., & Rivera, C. (1994). Is it real for all kids? A framework for equitable assessment policies for English language learners. Harvard Educational Review, 64 (1), 55-75.

Liu, K., Spicuzza, R., & Erickson, R. (1996). Focus group input on students with limited English proficiency and Minnesota’s Basic Standards tests (Minnesota Report 4). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Liu, K., Spicuzza, R., Erickson, R., Thurlow, M., & Ruhland, A. (1997). Educators’ responses to LEP students’ participation in the 1997 Basic Standards testing (Minnesota Report 15). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Liu, K., & Thurlow, M. (1999). Limited English proficient students’ participation and performance on Minnesota’s statewide assessments: Minnesota Basic Standards reading and math, 1996-1998 (Minnesota Report 19). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Liu, K., Thurlow, M., Thompson, S., & Albus, D. (1999) Participation and performance of students from non-English backgrounds: Minnesota’s 1996 Basic Standards Tests in reading and math (Minnesota Report 17). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Quest, C., Liu, K., & Thurlow, M. (1997). Cambodian, Hmong, Lao, Spanish-speaking, and Vietnamese parents speak out on Minnesota’s Basic Standards tests (Minnesota Report 12). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Rivera, C., & Stansfield, C. (1998). Leveling the playing field for English language learners: Increasing participation in state and local assessments through accommodations. In R. Brandt, Ed., Assessing student learning: New rules, new realities (pp. 65-92). Arlington, VA: Educational Research Service.

Rivera, C., & Vincent, C. (1997). High school graduation testing: Policies and practices in the assessment of English language learners. Educational Assessment, 4 (4), 335-355.

Saville-Troike, M. (1991, Spring). Teaching and testing for academic achievement: The role of language development. [On-line]. NCBE Focus: Occasional papers in bilingual education, 4. http://www.ncbe.gwu.edu/ncbepubs/focus/focus4.htm

Stansfield, C. (1997). Experiences and issues related to the format of bilingual tests: Dual language test booklets versus two different test booklets. (ERIC Clearinghouse No. TM028299). (ERIC No. ED419002).

Stansfield, C., & Kahl, S. (1998, April). Tryout of Spanish and English versions of a state assessment. Paper presented at a Symposium on Multilingual Version of Tests at the AERA Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA.

Tarone, E. (1999). Expanding our vision of English language learner education in Minnesota: Implications of state population projections. MinneTESOL/WITESOL Journal, 16, 1-13.

Van de Vijver, F., & Hambleton, R. (1996). Translating tests: Some practical guidelines. European Psychologist, 1 (2), 89-99.

Zlatos, B. (1994, November). Don’t test, don’t tell: Is ‘academic red-shirting’ skewing the way we rank our schools? The American School Board Journal, 24-28.

Interview Script for Phase 1

Directions: Hello. My name is_________________. Thanks for helping me. I am going to ask you a few questions about the test you just took. I am trying to find out how I can make it a better test. Please answer the questions honestly. You can talk to me in Spanish or English. Please ask me if you do not understand something. I will be happy to answer your questions. If you want, at the end of the interview, I will tell you how many answers you got correct. Do you have any questions?

For each passage:

1. Was this reading passage difficult or easy to understand?

2. Why? What made it easy or difficult?

3. Were you familiar with this subject before you read the passage?

4. In general, what form of the questions did you use?

(English version, Written Spanish version, Spoken Spanish version, more than one)

5. If you could take the Basic Standards Reading Test next winter in both English and Spanish or just in English, which would you chose? Why?

For each test item:

1. Was this question easy? Was it difficult?

2. Why was it easy or difficult?

3. Which form of the question did you use?

(English version, Written Spanish version, Spoken Spanish version, more than one)

4. Were there any words in the Spanish or English question that you didn’t understand?

5. Why did you choose answer ___?

6. Why didn’t you choose the other answers?

Language Background Survey

Summary Table of Interview Responses to General Questions About the Readings