|

An Analysis of Accommodations Issues from the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Technical Report 51 Martha Thurlow, Laurene Christensen, Kathryn E. Lail December 2008 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Thurlow, M., L., Christensen, L. L., & Lail, K. E. (2008). An analysis of accommodations issues from the standards and assessments peer review (Technical Report 51). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Acknowledgments This study was commissioned by the Accommodations Monitoring Study Group of the Assessing Special Education Students (ASES) State Collaborative on Assessment and Student Standards (SCASS). Appreciation is extended to Vince Dean and Courtney Foster, study group co-chairs, as well as the members of the study group for their time and input on the report. The members of the study group for 2007-08 included the following: Joseph Amenta (Connecticut), Pam Biggs (North Carolina), Trinell Bowman (Maryland), Sheila Brown (North Carolina), Dena Coggins (Colorado), Cynthia Corbridge (Rhode Island), Vince Dean (Michigan), Karen Denbroeder (Florida), Courtney Foster (South Carolina), Elizabeth Gordon (South Dakota), Michael Harris (Wyoming), Tom Hicks (Arkansas), Jaqueline James (Mississippi), Don Kilmer (California), Judy Kraft (Washington), Jill Larson (Nebraska), Jo Ann Malone (Mississippi), Carla Osberg (Nebraska), Donna Tabat (Minnesota), and Linda Turner (South Dakota). The authors wish to thank the staff at the U.S. Department of Education and Sandra Warren, Coordinator of the ASES SCASS, for their support of this project. Additional thanks go to Ting Wang for her work in preparing the figures for publication. A Message from the Accommodations Monitoring Study Group Co-chairs In October 2006, the ASES SCASS Accommodations Monitoring Workgroup discussed providing more information to states about the monitoring of accommodations to address the question of how states meet the NCLB requirement that they routinely monitor the extent to which test accommodations are consistent with those provided during instruction, specifically for students with IEPs. We are disseminating that information in a series of three separate documents. Working in conjunction with NCEO, the first document from this project Hints and Tips for Addressing Accommodations Issues for Peer Review, a quick reference for states in preparing for peer review, was released in April 2007. This technical report is the second document in the series and provides a more comprehensive analysis of the peer review guidance information and the methodology used in the research. The technical report summarizes themes found across multiple peer reviews of state assessment systems. Our third document, to be released in 2009, will provide a more comprehensive professional development guide for states to establish or improve quality accommodations monitoring programs. Vincent J. Dean, Ph.D. Courtney Foster To meet the assessment requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), states must ensure the inclusion of students with disabilities, as well as provide for the appropriate use of assessment accommodations. Accommodations have been defined in a number of ways. In the CCSSO Accommodations Manual, accommodations were defined as "practices and procedures in the areas of presentation, response, setting, and timing/scheduling that provide equitable access during instruction and assessments for students with disabilities" (Thompson, Morse, Sharpe, & Hall, 2005, p. 14). More recently, accommodations have been distinguished from modifications by focusing on the validity of assessment results when the changes in testing materials or procedures are used. When assessment accommodations are used appropriately, students are best able to demonstrate their learning and schools are able to account accurately for what students do and do not know. Accommodations are addressed in NCLB peer reviews through Sections 4 and 6 of the Peer Review Guidance. We conducted a thematic analysis of peer reviewers’ comments for 50 states. Our goal was to identify common issues and examples of the types of evidence considered acceptable and not acceptable by peer reviewers. Four themes emerged in our analysis of peer review comments on accommodations in states’ submissions for review of their assessment systems: (1) Selection of accommodations (2) Agreement of assessment accommodations with instructional accommodations (3) Monitoring accommodations availability and use (4) Accommodations use provides valid inferences and meaningful scores about students’ knowledge and skills The process of identifying themes revealed that pulling information from peer reviewers’ comments provides findings that should be of interest to the states and test developers, and to anyone concerned about the quality of accommodated assessments. Many useful recommendations evolve from the comments. At the same time, the information has several limitations that may be due to the different review panels and reviewers’ attempts to deal with states in a positive manner. Assessment accommodations are changes in materials and procedures that enable the student to participate in an assessment in a way that allows the student’s knowledge and skills to be assessed rather than the student’s disabilities (Thurlow, Elliott, & Ysseldyke, 2003). This definition is consistent with broader definitions that define accommodations in general, such as the CCSSO Accommodations Manual, that defined accommodations as "practices and procedures in the areas of presentation, response, setting, and timing/scheduling that provide equitable access during instruction and assessments for students with disabilities" (Thompson, Morse, Sharpe, & Hall, 2005, p. 14). The goal of assessment accommodations is to remove causes of irrelevant variance in each student’s test performance, thereby producing a measure of each student’s knowledge and skills that is valid (Thurlow, Thompson, & Johnstone, 2007). Although the purpose of accommodations sounds relatively straightforward, carrying it out in practice is not so simple. Despite the fact that we have been attending to states’ accommodation policies since 1993 when the first report on these policies appeared (Thurlow, Silverstein, & Ysseldyke, 1993; Thurlow, Ysseldyke, & Silverstein, 1995), there still are many issues that surround accommodations. These issues range from the setting of policies themselves, to the implementation of the policies during state assessments, and to the monitoring of whether what is best practice is actually occurring (Ketterlin-Geller, Alonzo, Braun-Monegan, & Tindal, 2007; Thurlow, 2007). At the same time that our evidence-based knowledge about the effects of accommodations is emerging (Johnstone, Altman, Thurlow, & Thompson, 2006; Thompson, Johnstone, & Thurlow, 2004; Zenisky & Sireci, 2007), states are required to submit their standards and assessments for review by the U.S. Department of Education. One result of the review process that started in 2004 was that many states’ assessments were not approved due, in part, to the evidence that was submitted about accommodations. The purpose of this analysis was to summarize what the reviewers’ comments reveal about issues that states are facing as they ensure that students with disabilities have the opportunity to use accommodations during the state assessment. We examined comments that emerged from peer reviewers during the peer review process because reviewers provided comments as they reviewed states’ evidence, and then submitted these comments to the U.S. Department of Education for consideration before making a decision about the approval status of each state’s standards and assessments. Overview of the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Process To determine whether states meet the requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, the U.S. Department of Education begins by conducting a peer review process. Although the topic of each peer review may change, the process itself is used regularly by the Department to assist with decision making. The peer review process that focused on states’ standards and assessments started in 2004. Experts in the area of standards and assessment reviewed the evidence compiled by states to demonstrate that their assessment systems meet specific criteria outlined in a Peer Review Guidance document (U.S. Department of Education, 2004, 2007). The Peer Review Guidance criteria help ensure that assessments are appropriate for holding schools and school districts accountable under NCLB. (See Appendix A for the part of the 2004 Guidance document that addressed accommodations and was used by states during the review that was the subject of our analysis.) To prepare for the peer review process, each state compiled a set of evidence materials, including state statutes and regulations, test administrator manuals, board resolutions, and assessment reports to convince the peer reviewers that the state assessment system meets NCLB requirements. The reviewers, under the guidance of a U.S. Department of Education staff person, review the materials to determine the extent to which the state assessment system complies with NCLB requirements. The reviewers provided feedback to states, via the U.S. Department of Education, that included suggested changes required to meet NCLB requirements. The reviewers also provided guidance for improving the state’s assessment system. Some states received approval notification; other states were asked to provide additional evidence to the U.S. Department of Education. The peer review comments served two primary purposes: (1) comments from the peer reviewers were shared with each state to assist in making improvements to its assessment system, and (2) comments from the peer reviewers provided input to the Assistant Secretary for Elementary and Secondary Education so that decisions could be made about the approval of each state’s standards and assessment system. The critical elements that peer reviewers looked for in the states’ materials on accommodations were: (1) Providing an appropriate variety of assessment accommodations for students with disabilities (2) Ensuring that the use of assessment accommodations yields meaningful scores (3) Ensuring that the use of accommodations for students with disabilities is consistent with instructional approaches, as determined by a student’s IEP or 504 plan (4) Determining that assessment scores for students with disabilities, when administrated under accommodated conditions, allow for valid inferences about the students’ knowledge and skills (5) Establishing clear guidelines for including all students with disabilities in the regular assessment These elements are found in Sections 4.3 (fairness and accessibility of assessments to all students), 4.6 (evaluating the use of accommodations), and 6.2 (inclusion of all students in the assessment system) of the Peer Review Guidance document. In early rounds of the peer review process, several states did not provide sufficient evidence for the assessment accommodations criteria. The National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) was asked to document the results of the peer review process for the accommodations criteria. Some of the questions that were posed were: What accommodation criteria were addressed insufficiently by states? Based on the peer review notes and comments, what is acceptable evidence? What is insufficient evidence? What suggestions did the peers offer that might be helpful to other states? This report provides the methodology and results of the NCEO thematic analysis of peer reviewers’ comments to the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. We identified themes in the peer review comments, and then identified information and examples that would be useful to states in responding to accommodation criteria in the Standards and Assessment Peer Review process. As we did in a tool that was developed for states as a result of our analyses (see Christensen, Lail, & Thurlow, 2007), in this report we highlight evidence from the Standards and Assessments Peer Review process, including acceptable and insufficient evidence for the accommodations elements. We also provide details of the methodology and limitations of the analyses, as well as specific examples of evidence. Three parts of the Standards and Assessment Peer Review Guidance were the focus of our analysis—two from Section 4 (A System of Assessments with High Technical Quality) and one from Section 6 (Inclusion of All Students in the Assessment System). In Section 4, we examined subsection 4.3, which focused on fairness and accessibility of assessments, and subsection 4.6, which focused on evaluating the use of accommodations. In Section 6, we examined subsection 6.2, which focused on the inclusion of all students in the assessment system. For all sections, we read and entered into tables all accommodations-related peer reviewer comments in each subsection as well as any overall summary comments pertaining to accommodations for a section. We examined peer review comments as of December 2006. Some states had received approval for their systems and had one set of comments. Other states were in the process of submitting additional evidence for review. Still others had more than one set of comments because they had been through more than one round of reviews. We used all rounds of review available to us at the time of the study as a basis for analysis to aid in identifying themes and examples of both acceptable and insufficient evidence of those themes. All relevant comments were compiled in a grid of the critical elements and their descriptors, the evidence provided by states, and peer comments. This grid was organized alphabetically by state and by critical element. This process resulted in extensive documents, with 120 pages for Section 4.3, 63 pages for Section 4.6, and 143 pages for Section 6.2. Validity Check We shared the preliminary results of our analyses with the U.S. Department of Education assessment team in early December as a check on the themes we had derived and as a validity check on the acceptable and insufficient examples we proposed pulling from the evidence states had submitted to the U.S. Department of Education. The assessment team supported the peer review process by convening peer reviewers, and communicating information from reviewers to the states. We discussed with the assessment team members our methodology, as well as the initial findings of our work. As a result of our meeting with the U.S. Department of Education assessment team, revisions were made in the scope of our analyses. It was agreed that we would focus our work on Section 4, specifically Subsections 4.3 and 4.6. Section 6.2 was dropped from analysis for two reasons. First, the intent of that section was to address alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards. Knowledge and research in the field on accommodations for these assessments are limited, as was the peer reviewers’ understanding of these alternates. Second, we agreed with the assessment team’s recommendation to look carefully at the first 10 states to receive approval for their assessment systems by the Assistant Secretary of Elementary and Secondary Education. It was suggested that these states were unique in obtaining quick approval of their entire assessment system, and would have valuable evidence to provide even if peer reviewers’ comments did not obviously reveal the evidence through their comments. Additional Analysis: Materials from the First 10 Approved States Based on the team’s recommendation that we add the first 10 states that received approval into our pool to examine for acceptable evidence, we used as examples both those states identified directly through peer review notes, and those states supported by notes and first-10 approval. The first 10 states to receive federal approval for their standards and assessments are, in alphabetical order:

In this document, we highlight the examples for each theme from these first-10 approved states as well as states that had comments clearly noted as exemplary. During the process of our review, it became apparent that not all peer reviewers were commenting in the same way when they reviewed the accommodations criteria in the Peer Review Guidance document. It is important to recognize that the two sections on which we focused (4.3 and 4.6) were just two out of 39 specific criteria that peer reviewers were asked to evaluate. In addition, peer reviewers’ expertise areas differed, including those with expertise in measurement, large-scale assessments, and standards. There was an attempt to have each team include a person who was familiar with issues of assessing students with disabilities or English language learners, but these individuals varied by peer review team in the extent of their familiarity. These characteristics of peer review teams necessarily affected to some degree the results of our analyses, which were based almost exclusively on peer reviewer comments and notes. Four themes emerged in our analysis of peer review comments on accommodations in states’ submissions for review of their assessment systems: (1) Selection of accommodations (2) Agreement of assessment accommodations with instructional accommodations (3) Monitoring accommodations availability and use (4) Accommodations use provides valid inferences and meaningful scores about students’ knowledge and skills In addition to these four themes, our analysis also revealed commonalities in how the peers addressed the small number of states that use a norm-referenced test for their statewide assessment in high school. The purpose of this report is to present those themes that were wide-reaching across states. Thus, more state-specific issues, such as the use of norm-referenced high school exams, are not discussed here. In the peer comments as well as in our own process of collecting additional documents from the evidence states provided for the peer review, we noticed that states used a variety of organizational approaches to collecting their materials. Some states gathered materials in binders, with tabs for each section. Other states used banker’s-style boxes with file folders for each piece of evidence. A few states organized their materials according to the different assessments used in their state. Other states combined their assessments into one set of materials. Labeling systems also varied greatly, with some states numbering their documents consecutively and other states using a numbering system reflective of the sections and critical elements from the guidance documents. For each theme that emerged from our analysis of peer reviewer comments and notes, we provide an explanation of the theme based on the criteria in the Standards and Assessment Peer Review process. We then highlight acceptable evidence for the theme, as well as examples of insufficient evidence, all based on the peer review notes. A list of helpful resources is also provided. Theme 1: Selection of Accommodations Selection of accommodations refers to the decision-making process used to determine which students should receive accommodations on statewide assessments and what accommodations are appropriate for each student. For this area of review, 47 states were seen to provide a variety of accommodations. Three states were asked to clarify who qualifies for accommodations for statewide testing. Three additional states were asked to provide additional evidence about the selection of accommodations. Two examples were selected to exemplify acceptable evidence for the Selection of Accommodations criteria. These were found in the peer review materials supplied by the states of Maryland and Delaware. Acceptable Evidence for "Selection of Accommodations" The Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance states that acceptable evidence includes "existing written documentation of the State’s policies and procedures for the selection and use of accommodations and alternate assessments, including evidence of training for educators who administer these assessments" (p. 37). Additional acceptable evidence in the Guidance includes the following: "The State assessment system must be designed to be valid and accessible for use by the widest possible range of students" (p. 37). In addition, acceptable evidence includes that the State has analyzed the use of specific accommodations for different groups of students with disabilities and has provided training to support sound decisions by IEP teams (p. 37). These statements are from Section 4.3. The evidence offered by Maryland was viewed as showing that an adequate variety of accommodations is offered. The reviewers noted that, "Examples of specific acceptable or un-acceptable accommodations are listed by various accommodation categories," including scheduling, setting, equipment/technology, presentation, and response accommodations. See Figure 1 for an example of Maryland’s accommodations decision-making chart. Maryland also clearly differentiates accommodation policies for students with disabilities, students with temporary or long term disabilities or Section 504 students, and English language learners. This type of differentiation is noted as a requirement in Section 4.6 of the Standards and Assessment Peer Review Guidance. Figure 1. Maryland’s Accommodations Decision-Making Chart Setting Accommodations Is the Accommodation Permitted? Yes (Y), No (N), or not applicable (NA).

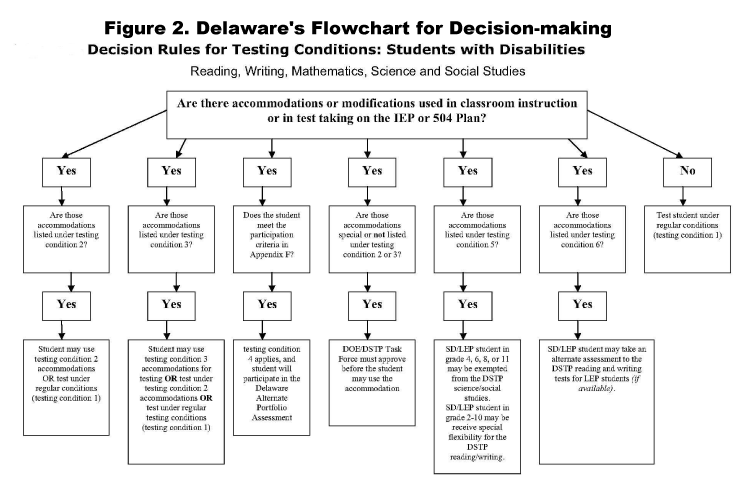

* Accommodations related to English language proficiency are not permitted for this test. In Delaware, a flowchart is used to guide decisions about testing accommodations. The reviewers noted this flowchart as acceptable "for placing students into the correct test and/or accommodations." In this flowchart, assessment accommodations follow directly from those accommodations used for instruction (see Figure 2 for Delaware’s Decision Rules for Testing Conditions: Students with Disabilities for an adapted version of the flowchart). Figure 2. Delaware’s Flowchart for Decision-making

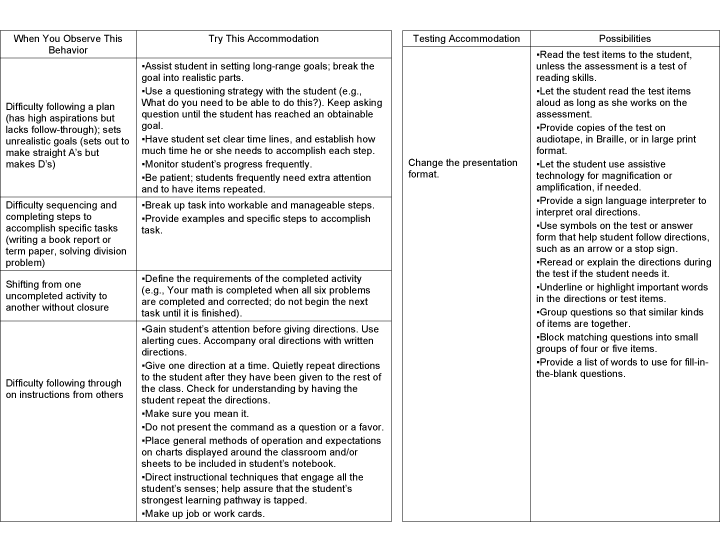

Insufficient Evidence for "Selection of Accommodations" The Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance, Section 4.6, states that one type of insufficient evidence is when a State "uses the same accommodations for limited English proficient students as it uses for students with disabilities" (p. 40). Several examples of insufficient evidence were identified by peer reviewers. We provide three examples here. These spanned more than three states. In one state’s accommodation selection criteria, there was no distinction made among accommodations for students with IEPs, accommodations for students with 504 plans, or accommodations for students who are English language learners. The reviewers advised this state "to provide separate lists of accommodations that would be allowable to individual students in each group to support the selection of appropriate accommodations that are aligned with instructional approaches for individual students." In more than one state, CCSSO’s (2005) Accommodations Manual was adopted as part of the state’s accommodations selection guidelines. However, the peer reviewers noted that in some cases, states did little to adapt the manual to the state’s own unique situation. The reviewers commented that the CCSSO document is general, and without adaptation to a state’s unique condition, it has no applicability to the state except as information. Another example of insufficient evidence is when a variety of accommodations are provided, but justification for accommodations is missing. In one instance, the reviewers stated, "There is no evidence available on how the allowable assessment accommodations were selected, who made the selection, and what available research was used in decision making. No information was provided about the expertise of the reviewers who reviewed the research to determine allowable accommodations." Theme 2: Assessment Accommodations are Consistent with Instructional Approaches Consistency of assessment accommodations with instructional approaches refers to the link between accommodations used during instruction and those used during assessment. CCSSO’s (2005) Accommodations Manual offers several important considerations, including the following: (1) It is importation to know which accommodations can be used for both instructional and assessment purposes. (2) Accommodations use should allow for students to have access to instruction and the opportunity to demonstrate learning. (3) Accommodations used for assessment should be routinely used for instruction. (4) Assessment accommodations should not be used for the first time on test day. (5) The goals of instruction and assessment should be considered before making decisions about accommodations. For example, if the assessment goal is to demonstrate calculation, then the use of a calculator would not be appropriate. However, if the assessment goal is to demonstrate problem solving, then the use of a calculator would be appropriate. The peer reviewers noted that 39 states met this requirement. Of those that did not 9 states were asked to provide additional evidence, and 5 states were asked to monitor assessment accommodations for their consistency with instructional accommodations. Two examples of evidence demonstrated what acceptable evidence was for the Agreement of Accommodations criteria. These were found in the peer review materials submitted by Alaska and Florida. Acceptable Evidence for "Agreement of Assessment Accommodations with Instructional Accommodations" The Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance states that possible evidence for the criteria about the agreement of assessment and instructional accommodations may include the routine monitoring of the extent to which test accommodations are consistent with those provided during instruction (p. 40). This statement, from Section 4.6, also focuses on monitoring, which is addressed in Theme 3. Alaska’s evidence demonstrates that accommodations used during testing are linked to accommodations used during instruction. Peer reviewers noted a key phrase in the state’s participation guidelines: "Because of the close link between assessment and instruction, the IEP or 504 plan must describe how accommodations for assessment are included in the student’s classroom instruction and assessment" (p. 13). This statement, according to the peer reviewers, "provides the assurance that IEP and 504 teams will think about accommodations for the student beyond a yearly test, and build connections between the classroom and the assessment setting." As part of the District Guide for Meeting the Needs of Students, which was submitted as evidence for this section, Florida has an extensive list of classroom accommodations for students with disabilities that starts from a list of student needs. This student needs-to-instructional accommodations list is in addition to the list of accommodations for taking tests (see Figure 3). The introduction to the test taking accommodations includes the following statement: "In general, students with disabilities should be provided the same types of accommodations for both assignments and assessments." The variety of both instructional and assessment accommodations is acceptable, and this statement begins to make the linkage between the use of accommodations for instruction and assessment. An even stronger link could be made between instructional and assessment accommodations by combining the two separate lists into one table that shows the connections for teachers and other decision makers. Figure 3. Florida’s Instruction and Test Accommodations Charts

Insufficient Evidence for "Agreement of Assessment Accommodations with Instructional Accommodations" The Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance, in Section 4.6, states that insufficient evidence may include the following: The State does not require that decisions about how students with disabilities will participate in the assessment system be made on an individual basis or specify that these decisions must be consistent with the routine instructional approaches as identified by each student’s IEP and/or 504 plan (p. 40). Numerous examples of insufficient evidence about the agreement between assessment accommodations and instructional accommodations were identified by peer reviewers. We provide three examples. These were evident in more than one state. Some states provided a list of accommodations, but the linkage of testing accommodations to accommodations used during instruction was not clear. To one state, the peer reviewers commented: "While the state has prepared a list of accommodations for students with disabilities, no evidence was presented that the state assures that the accommodations are used in a manner consistent with instructional approaches for each student. No evidence was presented that the state collects information on which accommodation(s) each student uses, either." Another state was cited as having no evidence of a link between instructional and assessment accommodations, even though there was an acceptable process for the selection of accommodations. In this example, the reviewers noted, "Neither the evaluation nor the presentation in the administration manual requires that the accommodation be used in instruction. The need for instructional comparability does not seem to be appreciated by the state." The reviewers also commented that "there should be a requirement that accommodations used in testing must have been used in instruction." One state provided examples of training materials that convey the expectation that assessment accommodations should only be used when they are also part of "ongoing instructional and classroom procedures." However, it was noted by peer reviewers that the selection and use of accommodations is not monitored, so the assurance that assessment accommodations are the same as those used during instruction cannot be established. Theme 3: Monitoring Availability and Use Monitoring refers to tracking the use of accommodations and checking for the consistency with which they are available and used by students during instruction and during assessment. Monitoring can cover a range of activities from simply documenting who is supposed to receive an accommodation to actually going back to check on whether the accommodations to be received were actually delivered on the day of testing or during instruction. The purpose of monitoring is to ensure that the decisions that are made for individual students are carried out. Acceptable Evidence for "Monitoring" The Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance, in Section 4.6, states that possible evidence may include the routine monitoring of the extent to which test accommodations are consistent with those provided during instruction (p. 40). A total of 15 states were asked about monitoring in general. In addition, monitoring may also refer to monitoring the availability of accommodations for statewide assessments. Twenty-one states were seen to have met this additional monitoring requirement. Two examples of evidence were selected to show the nature of acceptable evidence for the Monitoring criteria. These were found in the peer review materials from West Virginia and Florida. In the first round of peer review, West Virginia was asked to submit additional evidence of monitoring. The state was asked to specify how it would monitor the selection and use of accommodations beyond compliance, how the state would monitor administration procedures, and how the state would ensure that allowable assessment accommodations are limited to those used for instruction. Florida had several acceptable components of monitoring, including the following acceptable evidence: • The state conducts monitoring visits that include IEP reviews and interviews of teachers and administrators. Districts must provide assurance that students with disabilities are given appropriate accommodations. • At the time of testing, the state records information about accommodations. The state reviews and reports information about accommodations use on the FCAT for reading and math on an annual basis. • Targeted monitoring of schools and school districts is conducted. This includes reviewing records of individual students with disabilities for verification that the student received appropriate accommodations. Insufficient Evidence of "Monitoring" One example of insufficient evidence of monitoring, according to Section 4.3 of the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance, is that "The State does not train or monitor personnel at the school, LEA, and State levels with regard to the appropriate selection and use of accommodations and alternate assessments" (p. 37).. In many instances, states did not provide any evidence of monitoring the availability and use of accommodations. The lack of evidence was a common type of insufficient evidence. Two examples of insufficient evidence are provided here. One state has no policy on monitoring. In this state, the IEP team documents accommodation decisions on the IEP. There is an order form for accommodations but it is only a suggestion, not required or returned to the state department of education. Adapting this existing accommodations order form to make it part of a required monitoring process would be useful. Another state has a plan to conduct studies to monitor and evaluate the use of accommodations, but according to reviewers, these plans are not sufficient or appropriately targeted. Monitoring suggestions, made by the reviewers, included the following: (1) Surveys or observations regarding accommodations assignment (e.g. samples of IEPs compared to accommodations, larger than that proposed) followed by random audits/monitoring (2) Studies comparing external judgments of proficiency (e.g. teacher ratings on standards, overall grades) with test results with and without accommodations, if possible (3) Application of existing research to selection of accommodations (4) Studies of the effects of invalidating modifications, particularly for the [high school proficiency exam] (5) Formal reviews of literature, collection of expert judgment, and empirical evidence regarding what accommodations produce more valid scores for which students Theme 4: Accommodations Use Provides Meaningful Scores and Valid Inferences about Students’ Knowledge and Skills When used, accommodations must provide meaningful scores, ones that mean the same as scores produced by students who did not use accommodations. As Thurlow, Elliott, and Ysseldyke (1998) explained, "When scores do not mean the same thing, the integrity of the assessment is compromised" (p. 62). In such cases, accommodated scores may not be able to be combined meaningfully with non-accommodated test scores. Under NCLB and IDEA, it is imperative to report all assessment scores, and appropriate reporting requires all scores to be included. When used, assessment accommodations should enable the user of test results to have an accurate measure of what the student knows and is able to do. Thurlow, Elliott, and Ysseldyke (2003) explained that, "Without accommodations for their disabilities, an assessment may inaccurately measure what these students know and are able to do. The measure will reflect the disability rather than the student’s knowledge and skills" (p. 30). With appropriate accommodations educators can make valid inferences about students’ knowledge and skills. Seven states were specifically asked to provide additional evidence to demonstrate that accommodations yield meaningful scores. Seven states (four the same, three new states) were also asked to provide further evidence that accommodations use produces valid test scores. Maryland and Delaware both were described as having acceptable evidence with regard to accommodations use providing meaningful scores and valid inferences about students’ knowledge and skills. Acceptable Evidence for "Accommodations Provide Meaningful Scores and Valid Inferences" The Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance, in Section 4.6, states that acceptable evidence includes documentation that "the State provides for the use of appropriate accommodations and has conducted studies to ensure that scores based on accommodated administrations can be meaningfully combined with scores based on the standard administrations" (p. 40). Acceptable evidence from Section 4.6 includes the following: "The State has analyzed the use of specific accommodations for different groups of students with disabilities and has provided training to support sound decisions by IEP teams" (p. 40). With regard to acceptable evidence for valid inferences, one statement of acceptable evidence is the following: "The State is conducting studies to determine the appropriateness of accommodations and the impact on test scores" (p. 37). This statement is from Section 4.3 of the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance. Two examples of evidence were selected to portray what acceptable evidence was for the Monitoring of Accommodations criteria. These were found in the peer review materials provided by the states of Maryland and Delaware. In Maryland, accommodations that invalidate the score are clearly prohibited. See Figure 4 for an example of Maryland’s decision-making chart, which shows that accommodations that produce invalid scores are not permitted. Figure 4. Maryland’s Decision-Making Chart Presentation Accommodations Is the Accommodation Permitted? Yes (Y), No (N), or not applicable (NA).

* Accommodations related to English language proficiency are not permitted for this test. ** Use of Kurzweil™ reading software is permitted to deliver the accommodation. *** Not permitted for the Maryland Functional Reading Test. + Verbatim reading is only permitted on Part 6 ("Reading for Life Skills") and Part 4 ("Reading for Understanding Sentences") of the IPT Early Literacy Reading test and Part 3 ("Reading for Understanding") and Part 4 ("Reading for Life Skills") of the IPT 1, 2, and 3 Reading tests. Other test sections assess decoding skills for which verbatim reading is not appropriate or permitted.++ Verbatim reading invalidates the score for grades 3 and 4 general reading processes which measure language decoding skills. The score for students receiving this accommodation will be based on the remaining content of the test.

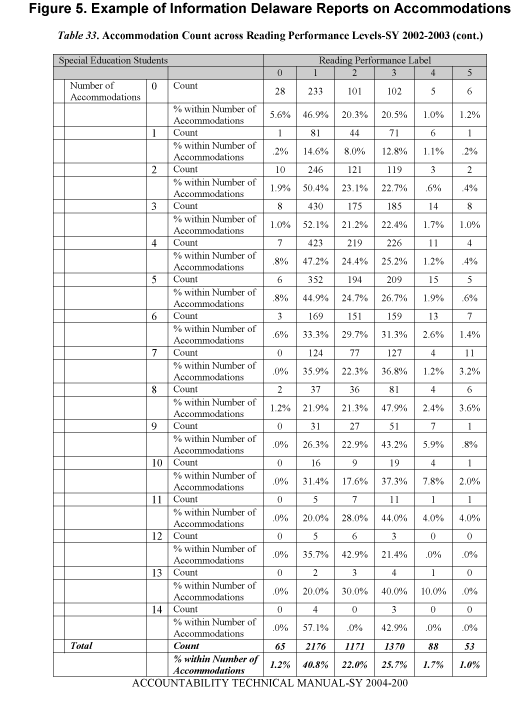

Delaware includes in its Accountability Technical Manual the "disaggregation of accommodation usage. In addition, the accommodation guidelines provide which accommodations can be aggregated into the accountability system." Although the peer reviewers recommended that Delaware consider a more results-oriented evaluation of the interpretation of scores under accommodated administrations, the reviewers also noted that they considered the state’s evidence as acceptable. Information about Delaware’s Accountability System can be found online at the Delaware Department of Education website. Figure 5 illustrates one example of how Delaware reports the use of accommodations in the accountability system. Figure 5. Example of Information Delaware Reports on Accommodations

Insufficient Evidence for "Accommodations Provide Meaningful Scores and Valid Inferences" In terms of meaningful scores, Section 4.6 of the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance states that insufficient evidence includes when the state has not conducted analyses "to determine whether specific accommodations produce the effect intended." Another example of insufficient evidence, also from Section 4.6, is when the state "uses the same accommodations for limited English proficient students as it uses for students with disabilities." Section 4.6 gives another example of insufficient evidence for accommodations providing meaningful scores when the state "does not require that decisions about how students with disabilities will participate in the assessment system be made on an individual basis or specify that these decisions must be consistent with the routine instructional approaches as identified by each student’s IEP and/or 504 plan." With regard to valid inferences, insufficient evidence is primarily when "no analyses have been carried out to determine whether specific accommodations produce the effect intended." This statement is from Section 4.6. Numerous examples of insufficient evidence were identified by peer reviewers. In some situations, states did not provide evidence for all assessments. This was a common example of insufficient evidence that accommodations provide meaningful scores. In one state, the test contractor does not report results by accommodation. The reviewers noted that as a result "it is difficult to determine the effectiveness of accommodations and whether they yield valid and meaningful results." One state provided evidence that because accommodations used in the state are those typically provided elsewhere, these accommodations allow for valid inferences about students’ achievement. However, the peer reviewers stated, "This is not evidence, however, that accommodations will permit valid inferences about students’ knowledge and skills. . . . Reviewers did not see evidence that the state permits accommodations to be used that allow for valid inferences about student knowledge and skills for both students with disabilities and English language learners." For another state, the reviewers commented, "Evidence is needed of how scores for students that are based on accommodated administration conditions are valid representations of performance relative to standards and how those scores may be meaningfully aggregated with scores from non-accommodated test administrations." Discussion and Recommendations Our analysis of peer review comments from the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance identified many examples of acceptable evidence and insufficient evidence. The four themes that emerged cut across the sections of the Peer Review Guidance document and emphasized the importance of the selection of accommodations, the agreement of instructional and assessment accommodations, the monitoring of accommodations, and the ability of accommodations to provide valid inferences and meaningful scores. The information from our analysis leads to several recommendations about developing evidence for accommodations peer review critiera. The findings, nonetheless, must be tempered by the realization that there were limitations introduced in our findings by the use of an approach that relied on peer reviewer comments. Reviewers had boxes of evidence to review for each state, and the information on accommodations was one small part of the review. Reviewers also tended to try to find a few positive comments that could be made for each state. If a state generally did not do well in the review process, it could have been the case that positive comments made to ease the effect of many negative comments happened to be made on the accommodations criteria. Despite these limitations, however, the analysis does lead to several recommendations. They are presented here in terms of the four themes. Recommendations for the Selection of Accommodations States hoping to meet requirements that involve accommodations in their assessments should attend to several reminders related to the selection of accommodations:

Recommendations for the Agreement of Assessment Accommodations with Instructional Accommodations States looking to demonstrate the agreement of assessment and instructional accommodations must be very explicit about how they are taking practical and consistent steps to ensure that assessment accommodations are aligned with instructional accommodations in an appropriate manner. Several reminders may help in meeting requirements and preparing evidence:

Recommendations for Monitoring Accommodations Availability and Use To improve in the area of Monitoring Accommodations Availability and Use, states are advised to develop a plan for tracking the use of accommodations, examining the data they receive, and doing something with and about those data. Some reminders for states are:

Recommendations for Ensuring that Accommodations Use Provides Valid Inferences and Meaningful Scores about Students’ Knowledge and Skills States hoping to demonstrate the extent to which their accommodations allow for valid inferences about students’ knowledge and skills need to attend to the desire to have evidence about the use of accommodations by different groups of students with disabilities and, to the extent possible, studies on the appropriateness of accommodations or their impact on test scores. It is recognized that there are constraints on conducting studies, including small samples and limited capacity. Still, studies that include interviewing students about the appropriateness of accommodations are among those that might provide useful information about this topic. States seeking positive peer review comments in this area must ensure that they have addressed the extent to which the scores that are obtained from assessments on which students have used accommodations are just as meaningful as the scores from assessments on which no accommodations are used. The following are some ideas for providing evidence to do so:

The four themes identified through our analyses were presented separately. In actuality, the themes are highly interconnected. In one case, the peers themselves demonstrate these connections with their comments to a state: [It] provided no evidence that its accommodations…yield meaningful scores and did not express any intent to research linguistic or special education accommodations. If (1) the list of allowable accommodations was based upon findings in the research literature, (2) the state provides clear guidance on the selection of particular accommodations for individual students, and (3) the state monitors and evaluates the use of accommodations, it may not be necessary for the state to conduct its own empirical studies regarding the comparability of scores from various administration conditions. However, there are clear limitations in the state’s forms for documenting accommodation selection and it appears the state does not have a system in place for monitoring selection or use at the time of testing. It is not enough to have a list of available accommodations. Rather, accommodations must be used for instruction and assessment, they must be monitored, and they must be used appropriately so that scores are valid and provide information about a student’s knowledge and skills. When testing accommodations are selected appropriately, used in a manner consistent with instruction, monitored, and proven to provide valid and meaningful scores, states can demonstrate that fair and accessible accommodations are available to all students, as required under NCLB. The following Web sites may be useful to states that wish to further explore information on accommodations for students with disabilities: Council of Chief State School Officers (http://www.ccsso.org) One useful publication is the Glossary of Assessment Terms and Acronyms Used in Assessing Special Education Students. This publication is available online at (http://www.ccsso.org/content/pdfs/ASESSCASSGlossary.pdf). In addition, the Assessing Special Education Students (ASES) State Collaborative on Assessment and Student Standards (SCASS) has developed an accommodations manual and accompanying professional development guide. These are available online in both Word and PDF formats. (http://www.ccsso.org/projects/scass/projects/assessing_special_education_students/11302.cfm) Grants.gov (http://www.grants.gov) This Web site has information on current federal grants, including grants on topics in education. National Center on Educational Outcomes (http://nceo.info) NCEO provides national leadership in the participation of students with disabilities in national and state assessments, standards-setting efforts, and graduation requirements. NCEO has several resources on accommodations including the Hints and Tips for Addressing Accommodations Issues for Peer Review (http://cehd.umn.edu/nceo/OnlinePubs/PeerReviewAccomm.pdf), the Data Viewer, which has information on current accommodations policies (http://data.nceo.info), and the Accommodations Bibliography, a searchable database of research on accommodations (http://apps.cehd.umn.edu/nceo/accommodations/). Office of Special Education Programs (http://www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/osers/osep/index.html) One useful resource available on the OSEP Web site is the Toolkit on Assessing Students with Disabilities (http://www.osepideasthatwork.org/toolkit/index.asp). Regional Resource and Federal Centers Network (http://www.rrfcnetwork.org) The six RRCs and the FRC are funded by the federal Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) to assist state education agencies in the systemic improvement of education programs, practices, and policies that affect children and youth with disabilities. These centers offer consultation, information services, technical assistance, training, and product development. United States Department of Education (http://www.ed.gov) Several important resources are available on the Ed.gov Web site. The federal standards and assessment peer review guidance can be found in their entirety (http://www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/guid/saaprguidance.pdf). In addition, federal regulations for alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards can be found (http://www.ed.gov/legislation/FedRegister/finrule/2003-4/120903a.html) in addition to regulations for alternate assessments based on modified achievement standards (http://www.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/modachieve-summary.html). Alaska Department of Education and Early Development. (2005) Participation guidelines for Alaska students in state assessments: Limited English proficient and special education. Juneau, AK: Author. Bureau of Exceptional Education and Student Services, Florida Department of Education. (2005). The IEP team’s guide to FCAT accommodations. Tallahassee, FL: Author. Bureau of Instructional Support and Community Services, Florida Department of Education. (2003). Accommodations and modifications: What parents need to know. Tallahassee, FL: Author. Hints and tips for addressing accommodations issues for peer review. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Delaware Department of Education. (2006). Accountability technical manual. Dover, DE: Author. Delaware Department of Education. (2005). Delaware student testing program guidelines for inclusion of students with disabilities and students with limited English language proficiency. Dover, DE: Author. Johnstone, C. J., Altman, J., Thurlow, M. L., & Thompson, S. J. (2006). A summary of research on the effects of test accommodations: 2002 through 2004 (Technical report 45). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Ketterlin-Geller, L. R., Alonzo, J., Braun-Monegan, J., & Tindal, G. (2007). Recommendations for accommodations: Implications of inconsistency. Remedial and Special Education, 28 (4), 194-206. OSEP (2005). Topic: Monitoring, Technical Assistance, and Enforcement Available online at http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/%2Croot%2Cdynamic%2CTopicalBrief%2C24%2C Maryland State Department of Education. (2004). Requirements for accommodating, excusing, and exempting students in Maryland assessment programs. Baltimore, MD: Author. A summary of research on the effects of test accommodations: 1999 through 2001 (Technical Report 34). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Thompson, S. J., Morse, A. B., Sharpe, M., & Hall, S. (2005). Accommodations manual: How to select, administer, and evaluate use of accommodations for instruction and assessment of students with disabilities. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers. Thurlow, M. L., Ysseldyke, J. E., & Silverstein, B. (March, 1993). Testing accommodations for students with disabilities: A review of the literature (Synthesis Report 4). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Thurlow, M. L. (2007). State policies and accommodations: Issues and implications. In C. C. Laitusis & L. L. Cook (Eds., Large-scale assessment and accommodations: What works? Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children. Thurlow, M. L., Ysseldyke, J. E., & Silverstein, B. (1995). Testing accommodations for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 16 (5), 260-270. Thurlow, M. L., Elliott, J. L., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2003). Testing students with disabilities: Practical strategies for complying with district and state requirements (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Thurlow, M., Thompson, S., & Johnstone, C. (2007). Policy, legal, and implementation issues surrounding assessment accommodations for students with disabilities. In L. Florian (Ed.), The Sage Handbook of Special Education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. U.S. Department of Education. (2004). Standards and assessments peer review guidance: Information and examples for meeting requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. Washington, DC: Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. West Virginia Department of Education. (2005). 2005-2006 West Virginia guidelines for participation in state assessments. Charleston, WV: Author. Zinesky, A. L., & Sireci, S. G. (2007). A summary of the research on the effects of test accommodations: 2005-2006 (Technical Report 42). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Peer Review Sections Relevant sections in the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance for Theme 1 Section 4.3 (a) Has the State ensured that the assessments provide an appropriate variety of accommodations for students with disabilities (p. 37)? Section 4.6 (a) How has the State ensured that appropriate accommodations are available to students with disabilities and that these accommodations are used in a manner that is consistent with instructional approaches for each student, as determined by a student’s IEP or 504 plan? (p. 40). Relevant sections in the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance for Theme 2 4.6 (a) How has the State ensured that appropriate accommodations are available to students with disabilities and that these accommodations are used in a manner that is consistent with instructional approaches for each student, as determined by a student’s IEP or 504 plan? (p. 40) Relevant sections in the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance for Theme 3 4.3 Has the State ensured that its assessment system is fair and accessible to all students, including students with disabilities and students with limited English proficiency, with respect to each of the following issues: (a) Has the State ensured that the assessments provide an appropriate variety of accommodations for students with disabilities? and (d) Does the use of accommodations and/or alternate assessments yield meaningful scores? (p. 37) 4.6 Has the State evaluated its use of accommodations? (a) How has the State ensured that appropriate accommodations are available to students with disabilities and that these accommodations are used in a manner that is consistent with instructional approaches for each student, as determined by a student’s IEP or 504 plan? Relevant sections in the Standards and Assessments Peer Review Guidance for Theme 4 4.3 (d) Does the use of accommodations and/or alternate assessments yield meaningful scores? (p. 37) 4.6 (b) How has the State determined that scores for students with disabilities that are based on accommodated administration conditions will allow for valid inferences about these students’ knowledge and skills and can be combined meaningfully with scores from non-accommodated conditions? (p. 40) |