Synthesis Report 97Graduation Policies for Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities Who Participate in States’ AA-AASMartha L. Thurlow, Debra A. Albus, Sheryl S. Lazarus, and Miong Vang December 2014 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Thurlow, M. L., Albus, D. A., Lazarus, S. S., & Vang, M. (2014). Graduation policies for students with significant cognitive disabilities who participate in states’ AA-AAS (Synthesis Report 97). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Table of Contents

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to acknowledge the quick responses that states provided to our request for verification of information we found on their websites. In addition, we are indebted to several individuals who reviewed this report and who provided excellent suggestions for revisions:

Top of Page | Table of Contents Executive SummaryGraduation requirements and diploma options for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in states’ alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS) were the focus of this policy analysis. We found that nearly 70% of states’ policies indicated that students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS can receive a regular diploma. The criteria for doing so in these states were extremely varied, from those that have the exact same requirements to those that allow the IEP team to set the criteria. In states with policies that indicated that students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS could not receive a regular diploma, all but one state indicated that other end-of-school documents (e.g., certificates, special diplomas) were available to these students. States that allowed students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS to receive a regular diploma and states that did not both generally had one or more end-of school documents (other than the regular diploma) that were the same. Gathering the information on whether students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS could receive a regular diploma was a difficult task. The information was not easily found on states’ websites. Verification was used to confirm what was found or to provide information where none was found. Despite the difficulties that we encountered, the information that we found and that was provided during our verification process provides important information for the field. Our findings should provide a basis for discussions within states as they consider their policies in light of college and career readiness imperatives. As a result of our analyses, we agree with the recommendations of Thurlow and Johnson (2013) for steps that states may want to take in addressing graduation requirements for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities:

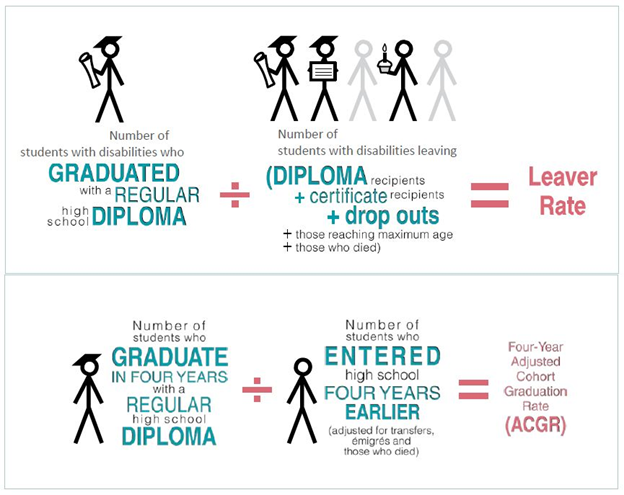

Top of Page | Table of Contents OverviewGraduation rates and requirements for earning a regular diploma are topics of increasing interest as states focus on ensuring that their students are college and career ready when they leave school with a diploma. Federal legislation—for example, Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)—has emphasized the importance of graduation from high school along with the prevention of students dropping out from school. Numerous educational organizations have also focused on graduation with a regular or advanced diploma as the pathway to post-high school success (e.g., Achieve, 2013; Alliance for Excellent Education, 2009; Cortiella, 2013; Hall, 2007). To ensure that states are gauging the rates at which students are graduating in a consistent way, ESEA now requires states to use a four-year adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR). This rate is defined as the number of students who graduate in four years with a regular high school diploma divided by the number of students who entered high school four years earlier (adjusted for transfers, émigrés, and those who died). This rate is quite different from other rates (Urban Institute, 2014), including the one-year rate that many states used in the past. For example, some states based their graduation rate on the number of students who entered grade 12 in the fall of a year and completed with a diploma in the spring of the same year. ESEA requires that states report the four-year ACGR overall and by subgroups, including students with disabilities who have Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). Having a common measure of graduation brings consistency across states, but the calculation of the ACGR is also different from the procedure used by the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) to report on students with disabilities (Urban Institute, 2014). OSEP requires that states report a Leaver Rate, which for graduation with a regular diploma involves dividing the number of students with disabilities ages 14 and older earning a regular high school diploma by the number of students with disabilities ages 14 and older leaving school either by earning a diploma, a certificate, or other document, or by dropping out (adjusted for those students who had reached maximum age and those who had died). Figure 1 provides a comparative illustration of the ESEA and OSEP approaches to calculating graduation/leaver rates. Graduation rates for students with disabilities historically have lagged behind those for students without disabilities. For example, the U.S. Department of Education (2010) estimated that the graduation rate for special education students is about 50%, compared to a national graduation rate that is about 75% (Stillwell, Sable, & Plotts, 2011). Yet, these data were based on still another calculation method—the averaged freshman graduation rate (AFGR). AFGR is used by the National Center on Education Statistics to estimate, without having individual student data, the proportion of high school freshmen who graduate with a regular diploma four years after starting ninth grade (Balfanz, Bridgeland, Bruce, & Fox, 2013). Figure 1. Illustrations of Calculations for Leaver (OSEP) and Graduation (ESEA)

Figures reprinted with permission from the National Center for Learning Disabilities. Source: Cortiella, C. (2013). Diplomas at risk: A critical look at the graduation rate of students with learning disabilities (pp. 9, 13). New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities.The ACGR data, which are based on individual student data files, shed additional light on what is happening for the special education subgroup, and it has been quite sobering. For example, for the 2010-11 school year, ACGR for students with disabilities ranged from 23% (Mississippi and Nevada) to 84% (South Dakota), and gaps between all students and students with disabilities were as high as a 52-percentage point difference (Cortiella, 2013). For 2011-12, the ACGR for students with disabilities ranged from 24% (Nevada) to 81% (Montana); the gaps between all students and students with disabilities was as high as 43% in 2011-12 (Stetser & Stillwell, 2014). Considerable attention has been given to those students with disabilities who participate in states’ general assessments. Recently, attention has turned to those students who participate in states’ alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS). It is less clear whether these students are permitted to earn regular high school diplomas when they leave school, and how they might factor into the ACGR calculations. Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities are a diverse group of students; still, they have several consistent characteristics that help in understanding their needs (Kearns, Towles-Reeves, Kleinert, Kleinert, & Thomas, 2011; Towles-Reeves et al., 2012; Towles-Reeves, Kearns, Kleinert, & Kleinert, 2009). For example, most of the students in this group (but certainly not all) have intellectual disabilities, multiple disabilities, or autism. Their numbers, relative to the general student population are small, perhaps in the range of 0.5 to 1.0% (these percentages vary considerably by state and district). Some of these students (around 15%) can read fluently, in print or braille, with basic understanding; about 50% can do basic computational procedures (with or without a calculator). Still, others have low levels of expressive communication and perhaps low levels or inconsistent levels of receptive communication. The National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) has conducted several surveys of states to learn more about diploma options, graduation requirements, and exit exams for youth with disabilities (Johnson, Thurlow, & Schuelka, 2012; Thurlow, Cormier, & Vang, 2009). Surveys can provide a picture of the ways in which students can earn a regular diploma, including the ways in which students with the most significant cognitive disabilities can earn a diploma. Still, survey data are sometimes difficult to interpret, so there is a need for the analysis of states’ written policies on graduation requirements. States’ written policies provide documentation of current policies and practices for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, including whether they can earn a regular diploma. This view is particularly important to obtain because of the increasing emphasis on college and career readiness for all students, including those with the most significant cognitive disabilities (Kleinert, Kearns, Quenemoen, & Thurlow, 2013; Research and Training Center on Community Living, 2011). The purpose of this analysis of states’ graduation policies for their students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS was to address six questions:

Top of Page | Table of Contents MethodThree NCEO staff members searched state department of education websites for information on graduation options for students who participate in the AA-AAS. We specifically looked for information on: (a) whether students in the AA-AAS could receive a regular diploma; (b) the criteria that were identified for students to receive a regular diploma if that was an option; (c) whether alternate diplomas or certificate options were available to students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in the AA-AAS; and (d) the criteria that were identified for students to receive an alternate diploma or certificate option, if available. Following the documentation of information from states’ websites, we summarized what we found, including the source websites and documents (see Appendix A). An example of a completed form for one state is provided in Appendix B. After the information was compiled, each state director of special education was sent the form for his or her state to use for verification of our findings. The verification procedure took place during a window from April 29 to June 2, 2014. Forty-one states responded to the verification request during that window. For the remaining nine states, other individuals within the state departments of education were contacted for verification. By June 30, 2014 a total of 47 verification responses had been obtained from the 50 states (94%). During the verification process, we often received information about policies that we were not able to find on states’ websites. In these and other cases, state personnel provided to us their understanding of the policy. We accepted both—written documentation and feedback from the state during the verification process. After verification, states were first assigned to one of two groups based on whether they did or did not allow students who participated in the AA-AAS to receive a regular diploma. Next, states that allowed students in an AA-AAS to receive a regular diploma were further grouped into categories depending on the criteria that states reported using. The categories for states that allowed these students to receive a regular diploma indicated that students in AA-AAS: (a) must meet exactly the same state criteria as other students; (b) must meet exactly the same state criteria as other students, with variation for the test requirement; (c) must receive a proficient score on the AA-AAS; (d) may meet IEP-defined requirements; (e) may meet local district requirements; or (f) may meet other alternative state criteria (e.g., special course of study). To assign one criterion to each state, we prioritized the criteria on a scale from those closest to being the same as the criteria applied to students without disabilities to those farthest away. This prioritization is shown in Table 1. Table 1. Prioritized Criteria for Receiving a Regular Diploma

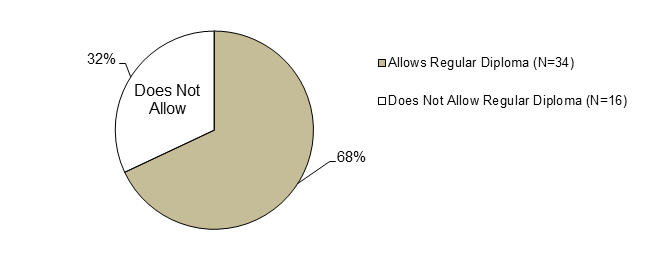

If a state appeared to fit into two or more categories, it was categorized into the criterion that was “farthest away” from the criterion used for all other students. For example, if a student needed to meet local district requirements but could also meet IEP-defined requirements, the IEP-defined requirement was considered to be less similar to what all other students needed to do, so that policy would be categorized as “Meet IEP-defined requirements.” For the states that allowed students participating in the AA-AAS to receive regular diplomas, we also identified any end-of-school documents (other than the regular diploma) that were available for those students who did not meet the regular-diploma graduation requirements. In addition we sought information on the requirements to earn any available end-of-school documents. Policies in states that did not allow students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in the AA-AAS to earn a regular diploma also were examined to identify the end-of-school documents that were available to their students. The criteria for earning these end-of-school documents also were explored. When categorizing state policies, it was possible that we did not have all the relevant information used in making a decision about whether a criterion was met. For example, a state might indicate that a student with a significant cognitive disability needed to have 21 credits, like other students, but not indicate whether those credits could be obtained by taking special non-equivalent classes. Because we could not discern this from the state website or from the state verification of our information, the state policy was classified literally. Top of Page | Table of Contents ResultsResults are organized by the six research questions. Following the research questions, we include a section that contains additional findings that we discovered during our analyses. These additional findings focus on: (a) the nature of the curriculum for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities; (b) parent knowledge about diploma options; and (c) the implications of a different end-of-school document for accountability. Extent to Which States Allow Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities to Earn a Regular High School Diploma (Research Question 1)The policies of 68% of the 50 states (N = 34) indicated that the state allowed students with the most significant cognitive disabilities participating in the AA-AAS to earn a regular diploma (see Figure 2). Appendix C (see Table C-1) provides state-by-state information on whether students participating in the AA-AAS can receive a regular diploma. Figure 2. Percent of States that Allow and Do Not Allow Students in AA-AAS to Receive Regular Diploma

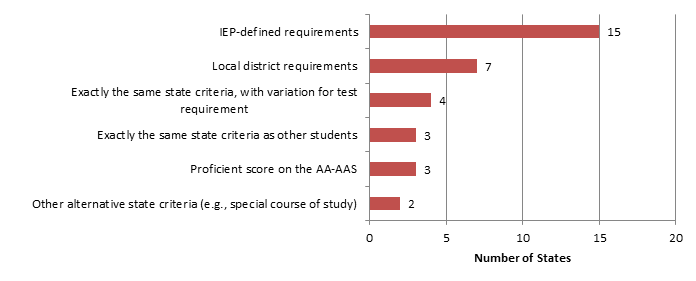

Requirements for Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities to Earn a Regular Diploma in States that Allow It (Research Question 2)For the 34 states that allowed students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in an AA-AAS to earn a regular diploma, we conducted an analysis of their categorized criteria. Figure 3 presents these criteria and the number of states whose criteria were in each category. (See Appendix C, Tables C-2 and C-3, for details.) Figure 3. Criteria for Students in AA-AAS to Earn a Regular Diploma

As indicated in the figure, most states (N=15) required students to meet IEP-defined requirements. Some states that referred to IEP-defined requirements did so in an “or” statement. For example, Pennsylvania indicated that the student who participated in the AA-AAS must either meet regular education graduation requirements or meet criteria established by the IEP team. In other states, the IEP team could alter the course requirements. For example, Utah’s policy indicated that the IEP can make course substitutions for a student to meet graduation requirements. Meeting IEP goals and objectives was a frequent approach that some states took. For example, as part of an “or” statement, Arkansas noted that students must either meet the regular graduation requirements or complete goals and objectives on the IEP. The seven states that referred to local district requirements for earning a regular diploma varied from simply stating that local districts set policies for graduation requirements to indicating that districts could adapt some of the state’s requirements. For example, Arizona indicated that the local school district governing board or charter school developed the course of study and graduation requirements for students in special education programs, but emphasized that these should not be different from the graduation requirements that apply to all students regardless of the state assessment in which the student participates. Colorado indicated that if alternate graduation requirements (e.g., district-determined demonstration of competency) were used for the student to earn a regular diploma, and the student met those requirements and received a regular diploma, that student would no longer be eligible to receive special education services. Four states indicated that students participating in the AA-AAS had to meet exactly the same state criteria for graduation with a regular diploma as other students, except that the test requirements could be altered. In a couple of the states (Oklahoma and Washington), the state indicated that students could meet the testing criterion of the graduation requirements by taking the AA-AAS (but not necessarily having to earn a proficient score). Washington added that students receive a regular diploma with a notation of “individual achievement” on the diploma. In both California and Illinois, students were exempted from taking the testing requirement for earning a regular diploma. The criterion of requiring the student to earn a proficient score on the AA-AAS was evident in three states’ policies on graduation requirements for students in the AA-AAS (Georgia, Idaho, and Massachusetts). Georgia’s policy indicated that the student must earn a proficient score on all the content areas of the Georgia Alternate Assessment (GAA). Similarly, Idaho indicated that the student had to earn a proficient score on the Idaho State Achievement Test—Alternate (ISAT-ALT). Massachusetts’s policy was less clear in that it indicated during verification that AA-AAS students must earn a “Needs Improvement” score level or better on the alternate based on grade-level achievement standards. Students who are working on grade-level achievement standards and students who are working on alternate achievement standards participate in the same portfolio assessment in Massachusetts. Three states unequivocally indicated that there was no change in the graduation requirements for a student with the most significant cognitive disabilities. For example, Hawaii indicated simply that students must complete the required 24 credits. Mississippi indicated that students must meet the same criteria as other students. Maine’s requirements for meeting the same criteria were less clear in that the criteria were those established by the district. End-of-School Documents Available to Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities Who Do Not Meet the Regular Diploma Requirements (Research Question 3)Of the 34 states that indicated students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in an AA-AAS could earn a regular diploma, 19 states (56%) either had other state end-of-school documents for those students who did not meet the criteria for the regular diplomas, or indicated that districts might issue other end-or-school documents to these students. The names and numbers of the other end-of-school documents varied considerably (see Table 2 and Appendix D, Table D-1). Most states that indicated there were other end-of-school documents available did not have another state-level end-of-school document, instead relying on districts to determine the other end-of-school documents available to students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who did not meet the requirements for earning a regular diploma. Nine states did have other state-level end-of-school documents for these students. Most of these states (N = 7) had Certificates of Completion. Other available state-level documents included Certificates, Certificates of Attendance, Occupational Diplomas, and Special Diplomas or Special Education Diplomas. Table 2. Other End-of-School Documents for Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities Not Meeting Requirements for Regular Diploma in States that Offer the Regular Diploma to Students Participating in the AA-AAS (N = 19)

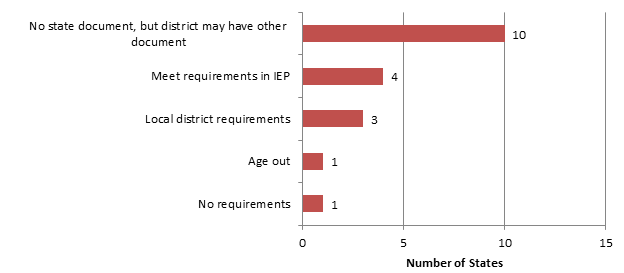

Note: Fifteen states (Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont, and Washington) reported that there was no other end-of-school state document; they did not indicate that districts could provide one (see Appendix D, Table D-2).1 States that have other end-of-school documents that were not identified by name on their websites or during the verification process do not include information about the document names in this table.Requirements for Other Documents that Students May Receive in States Allowing Students to Earn a Regular Diploma (Research Question 4)The criteria for earning other end-of-school documents also varied considerably (see Figure 4 and Appendix D, Tables D-2 and D-3). Ten states responded that there was no other state document, but that districts may decide to issue one; three other states specifically mentioned district-determined requirements. Four states indicated that the student had to meet IEP requirements. One state each noted aging out and having no requirements. Figure 4. Criteria for Other End-of-School Documents in States Where Student Can Earn a Regular Diploma and Where Another End-of-School Document is Available for Students Who Do Not Meet Regular Diploma Criteria (N = 19)

Most states indicated that there was no state document, but district may have other documents. In these states, the criteria were determined by the districts, and when information was available, seemed to vary widely. In some cases, the state provided the names of documents and criteria that districts were using; in others there was no information about the criteria that districts might be using. Must meet IEP requirements was the basis for receiving other end-of-school documents in four states. These requirements sometimes involved simply meeting IEP goals, but more often seemed to be slightly more prescriptive. For example, in California, requirements added to meeting IEP goals included satisfactorily attending high school, participating in prescribed instruction, and meeting objectives of transition services. Local district requirements had to be met in three states. The descriptions of the requirements in these states varied from simply indicating that each district determines the criteria (New Hampshire, Wyoming) to indicating that students could meet the district criteria if they had completed their senior year, were exiting the school system, and had not met all of the state or LEA requirements for a diploma. Age-out was the criterion used in one state. Specifically, Missouri, the state in which an other end-of-school document (Certification of Completion) was based on the student’s age, indicated that the Certificate of Completion would be given to students who age out at age 21. No requirements were identified for receiving an other end-of-school document (special education diploma) in one state (Georgia). End-of-School Documents in States that Did Not Allow Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities to Earn a Regular Diploma (Research Question 5)In the 16 states that did not allow students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in the AA-AAS to earn a regular diploma, a variety of end-of-school documents was available (see Table 3 and Appendix E, Table E-1). Certificates of Achievement were available in two states (Alaska and Louisiana), Certificates of Attendance in another two (Delaware and South Carolina), and Certificates of Completion in another two (Indiana and Maryland). The remaining states had a range of special diplomas, alternative diplomas, adjusted diplomas, and so on. Table 3. End-of-School Documents in States Not Allowing Students in the AA-AAS to Earn a Regular Diploma (N = 16)

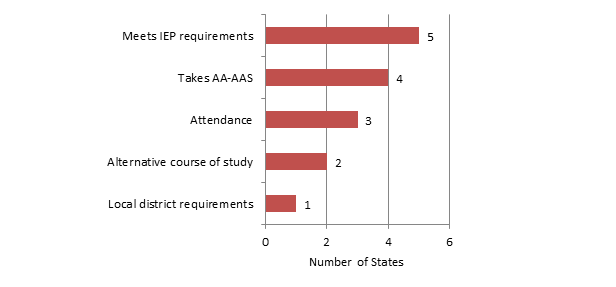

Requirements for Other Documents that Students May Receive in States that Did Not Allow a Regular Diploma (Research Question 6)Among the 16 states that did not allow students participating in an AA-AAS to earn a regular diploma, 15 offered other graduation options with separate criteria, such as meeting IEP requirements, taking an AA-AAS, or attendance (see Figure 5 and Appendix E, Tables E-2 and E-3). A small number of states mentioned district determined requirements and an alternative course of study. Just one state (Rhode Island) in this group indicated that no other documents were available to students who participated in an AA-AAS. Figure 5. Criteria for Other Documents in States that Did Not Allow a Regular Diploma

Meets IEP requirements often involved meeting IEP requirements along with meeting other criteria. For example, in North Carolina (Graduation Certificate), students have to successfully complete 21 course credits in high school as well as “pass” all requirements of their IEPs. Tennessee indicated that the Special Education Certificate is awarded to students who satisfactorily completed an IEP and a portfolio, and who have satisfactory records of attendance and conduct. In four states, taking the AA-AAS was the criterion for receiving another end-of-school document. For example, Louisiana simply indicated that its Certificate of Achievement is for students who take the Louisiana Alternate Assessment Level 1 (LAA1). Maryland indicated that the Certificate of Program Completion was available only to those students who, once they started to take the alternate assessment, took it for the duration of their schooling. The states that indicated attendance was the requirement for earning an end-of-school document did not have additional criteria. Two of these states had Certificates of Attendance (Delaware and South Carolina) and one had a Certificate of Achievement (Alaska). Other Information About Graduation Requirements for Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities Who Participate in the AA-AASAlthough we did not specifically look for information about the nature of the curriculum for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, parent knowledge about diploma options, or the implications of a different end-of-school document for accountability, some of this information did emerge in either our web search or during the state verification process. Although not comprehensive, we highlight the information that did emerge in these three areas. This information was not verified by other states. Nature of curriculum. Five states made some mention of functional performance or functional curriculum in criteria for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in the AA-AAS to graduate. Of these, four states mentioned it in the context of earning a regular diploma (Michigan, New Mexico, North Dakota, and South Dakota). New York mentioned it in the context of earning a separate credential. The specific language for each state is provided in Appendix F (see Table F-1). Parent knowledge about diploma options. Six states clearly mentioned parent knowledge of a diploma option either as a sign off on a form, having input, or being notified. Both Maryland and Rhode Island mentioned parent sign off or notification that a decision for AA-AAS participation did not lead to a regular diploma. Three states required parent notification about changing requirements or altering curriculum in order to earn a regular diploma (Montana, Ohio, and Oklahoma). Ohio and Oklahoma required this consent in writing. One state, Oregon, required parent consent for students participating in requirements toward earning an extended diploma. See Appendix F (Table F-2) for more detailed information on each state’s policy. Implications for accountability. Three states addressed whether regular diplomas earned by students participating in an AA-AAS count as a regular diploma for accountability reporting purposes. New York did not allow a regular diploma for students in AA-AAS and did not count a skills and achievement commencement credential for accountability purposes. Two other states, Utah and Wisconsin, allowed students in the AA-AAS to earn a regular diploma; Utah did not count it for accountability. Wisconsin allowed it to be counted for accountability if the district board policy permitted it. See Appendix F (Table F-3) for the language for each state’s policy. Top of Page | Table of Contents DiscussionThis investigation of the graduation requirements and diploma options for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in states’ AA-AAS revealed considerable variability in approaches. Although nearly 70% of states indicated that students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS can receive a regular diploma, the criteria used in those states are extremely varied, from those that have the exact same requirements of these students as of all other students, either with or without the same requirements for testing (N = 7) to those that allow the IEP team to set the criteria (N = 15). In those states in which students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS cannot receive a regular diploma, only one state indicated that there was no other end-of-school document available to these students. Most states had one or more other end-of-school documents (e.g., Certificates of Achievement or Attendance, Special Diplomas), and these were generally the same types of end-of-school documents available to students with the most significant cognitive disabilities in those states that allowed students to receive a regular diploma. Gathering the information on whether students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS could receive a regular diploma was a difficult task. The information is not easily found on states’ websites. Verification was used to confirm what was found or to provide information where none was found. Despite the difficulty in finding information, it was clear from the quick response of nearly all states to our requests for verification of information that states were very interested in the topic. In addition to the information being difficult to find, we often found that the information that did exist was not always very easy to interpret. One state indicated that students participating in the AA-AAS could receive a regular diploma, but to do so had to meet grade-level achievement standards. Another state seemed to indicate both that students had to meet exactly the same criteria as other students, but also indicated that districts set the criteria, making it difficult to discern whether districts actually could change the criteria. Our categorization of criteria in terms of their distance from the criteria used for students without disabilities also was difficult. Although we developed a reasonable ordered list, there are several factors that might make the order questionable in specific cases. For example, if a state had developed alternate achievement standards that were not based on rigorous performance requirements, it might be reasonable to order “Receive a proficient score on the AA-AAS” after “Meet other alternative state criteria (e.g., special course of study”), thus indicating that it was farther away from the criteria used for students without disabilities. Regardless of this, the categories that were used in our analysis provide a reasonable set of categories to use in describing states’ policies. We also found that in some states, despite a stated policy, there was clearly an interpretation that differed from that policy. For example, more that one of the states that indicated students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in the AA-AAS could receive a regular diploma also noted that this rarely happened, suggesting that policy differed from actual practice because of the difficulty of meeting the requirements, or perhaps that placement in the AA-AAS itself produced some unintended consequences, namely that students did not gain access to the general curriculum necessary to be able to meet the requirements. In our search, we also found one state that noted that the student with the most significant cognitive disabilities who participated in the AA-AAS would have a notation of “individual achievement” on the diploma. Because this type of occurrence was not a target of our search, we do not know whether similar notations were noted in other states, either on the diploma or elsewhere (e.g., on a transcript; see Thurlow et al., 2009). Both of the difficulties just mentioned (difficulty gathering information and difficulty interpreting information that was found) suggest that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, for most parents to figure out the requirements for their own child. Similarly, it is likely very difficult for educators to determine exactly what the criteria are for their students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. In our web searches, we also found that in most states minimal information was provided on the implications of states’ policies about whether parents of a student with the most significant cognitive disabilities were notified that participation in the AA-AAS would make their child ineligible for earning a regular diploma. There also was minimal information on whether a student participating in the AA-AAS who might earn a regular diploma would then be counted as a graduate in graduation rate accountability formulas. Implications for the curriculum or for accountability were generally lacking. It should be noted that we were not specifically seeking this information in our searches, nor during verification, but it was evident in some of the information that we found, suggesting that it possibly should be available in all states. Thurlow and Johnson (2013) recommended that states take the following steps in addressing the graduation requirements for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities:

Although many states have already established their policies, at this time when college and career readiness is a priority, it is well worth taking the time to engage again in considerations about the meaning of the regular diploma and its meaning for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. Top of Page | Table of Contents ReferencesAchieve. (2013). State college- and career-ready high school graduation requirements. Washington, DC: Achieve. Retrieved from: www.achieve.org/files/CCR-Diploma-Grad-Reqs-Table11-13.pdf. Alliance for Excellent Education. (2009). Every student counts: The role of federal policy in improving graduation rate accountability (Policy Brief). Washington, DC: Author. Balfanz, R., Bridgeland, J., Bruce, M., & Fox, J. H. (2013). Building a grad nation: Progress and challenge in ending the high school dropout epidemic–2013 annual update. Washington, DC: Civic Enterprises, the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University School of Education, America’s Promise Alliance, and the Alliance for Excellent Education. Cortiella, C. (2013). Diplomas at risk: A critical look at the graduation rate of students with learning disabilities. New York: National Center for Learning Disabilities. Retrieved from: www.ncld.org/images/content/files/diplomas-at-risk/DiplomasatRisk.pdf. Hall, D. (2007). Graduation matters: Improving accountability for high school graduation. Washington, DC: Education Trust. Johnson, D. R., Thurlow, M. L., & Schuelka, M. J. (2012). Diploma options, graduation requirements, and exit exams for youth with disabilities: 2011 national study (Technical Report 62). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Kearns, J. F., Towles-Reeves, E., Kleinert, H. L., Kleinert, J. O., & Thomas, M. K. (2011). Characteristics of and implications for students participating in alternate assessments based on alternate academic achievement standards. The Journal of Special Education, 45(1), 3-14. Kleinert, H., Kearns, J., Quenemoen, R., & Thurlow, M. (2013). Alternate assessments based on Common Core State Standards: How do they relate to college and career readiness? (NCSC GSEG Policy Paper). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center and State Collaborative. Research and Training Center on Community Living. (2011). Postsecondary education for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A critical review of the state of knowledge and a taxonomy to guide future research (Policy Research Brief). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Institute on Community Integration. Stetser, M. C., & Stillwell, R. (2014). Public high school four-year on-time graduation rates and event dropout rates: School years 2010-11 and 2011-12: First look (NCES 2014-391). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. Stillwell, R., Sable, J., & Plotts, C. (2011). Public school graduates and dropouts from the Common Core of Data: School Year 2008–09 (NCES 2011-312). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from: http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch. Thurlow, M. L., Cormier, D. C., & Vang, M. (2009). Alternative routes to earning a standard high school diploma. Exceptionality, 17(3), 135-149. Thurlow, M. L., & Johnson, D. R. (2013). Graduation requirements for students with disabilities: Ensuring meaningful diplomas for all students. Washington, DC: Achieve. Towles-Reeves, E., Kearns, J, Flowers, C., Hart, L., Kerbel, A., Kleinert, H., Quenemoen, R., & Thurlow, M. (2012). Learner characteristics inventory project report (A product of the NCSC validity evaluation). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center and State Collaborative. Towles-Reeves, E., Kearns, J., Kleinert, H., & Kleinert, J. (2009). An analysis of the learning characteristics of students taking alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards. Journal of Special Education, 42(4), 241-254. doi:10.1177/0022466907313451 Urban Institute. (2014). High school graduation, completion, and dropout (GCD) indicators: A primer and catalog. Washington, DC: Education Policy Center: The Urban Institute. U.S. Department of Education (2010). Twenty-ninth annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2007 (Vol. 2). Washington, DC: Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Programs. Top of Page | Table of Contents Appendix AState Documents Used in Analysis of Accommodation Policies

Top of Page | Table of Contents Appendix BExample State Profile of One StateVerification of Graduation Options for Students in AA-AAS Please review the following information for your state regarding graduation options for students in AA-AAS, and edit the content for accuracy. Summary of Graduation Options Available to Students in AA-AAS

Source(s) of Information NCEO Used Alabama Department of Education (2014). AHSG requirements LEA questions revised 6-10-13. Retrieved January 8, 2014 from: http://www.alsde.edu/general/New_Diploma_FAQs_Revised_6-6-13.doc For some students in the AA-AAS, they are working toward the Occupational Diploma. New diploma policy was introduced for 9th grade class of 2013-14.Updated text is below from FAQs. “What is the purpose in making this change?

33. Will the students on certificates be involved in this or will this be an IEP Team’s decision for those students with cognitive deficits?

Yes. AAA Life Skills offers school systems flexibility to utilize curriculum and instructional programs that address the three components of the Career Preparedness course.” Top of Page | Table of Contents Appendix CStates Allowing Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities Who Participate in the AA-AAS to Receive a Regular Diploma and the Criteria for Receiving the DiplomaTable C-1. States That Allow and Do Not Allow Students Participating in the AA-AAS to Receive a Regular Diploma

Table C-2. Criteria Used for Students Participating in AA-AAS to Earn a Regular Diploma

Table C-3. State Responses and Policy Language

Top of Page | Table of Contents Appendix DEnd-of-School Documents Available to Students Who do Not Meet Regular Diploma Criteria (in States that Allow Students Participating in the AA-AAS to Receive a Regular Diploma) (N = 34)Table D-1. Other End-of-School Documents in States that Allow a Regular Diploma

Table D-2. Criteria for Other End-of-School Documents that Students Participating in the AA-AAS May Earn, in States that Allow a Regular Diploma

Table D-3. State Responses and Policy Language

Top of Page | Table of Contents Appendix E

|

State |

Number of Other State End-of-School Documents |

Names of Other State End-of-School Documents |

Alaska |

1 |

Certificate of Achievement |

Delaware |

1 |

Certificate of Attendance |

Florida |

21 |

Special Diploma Option 1; Special Diploma Option 2 |

Indiana |

1 |

Certificate of Completion |

Kentucky |

1 |

Alternative High School Diploma |

Louisiana |

1 |

Certificate of Achievement |

Maryland |

1 |

Certificate of Program Completion |

Nevada |

1 |

Adjusted Diploma |

New York |

1 |

Skills and Achievement Commencement Credential |

North Carolina |

1 |

Graduation Certificate |

Oregon |

31 |

Modified Diploma; Extended Diploma; Alternative Certificate |

Rhode Island |

0 |

|

South Carolina |

1 |

Certificate of Attendance |

Tennessee |

1 |

Special Education Certificate |

Virginia |

1 |

Special Diploma |

West Virginia |

1 |

Modified Diploma |

Total 16 |

18 |

|

1 State has more than one state end-of-school document that fits within one criterion in Table E-2.

Table E-2. Criteria for Other Documents in States that Did Not Allow a Regular Diploma

State |

District determined criteria |

Attendance |

Takes alternate assessment based on AAS |

Meets IEP requirements |

Alternative course of study |

No other documents available |

Alaska |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Delaware |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Florida |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Indiana |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Kentucky |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Louisiana |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Maryland |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Nevada |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

New York |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

North Carolina |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Oregon |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Rhode Island |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

South Carolina |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Tennessee |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Virginia |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

West Virginia |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Total 16 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

Table E-3. State Responses and Policy Language

State |

State Responses and Policy Language |

Alaska |

Attendance: Certificate of Achievement – based on attendance |

Delaware |

Attendance: Certificate of Attendance |

Florida |

Alternative course of study: Special Diploma Option 1 – must meet district requirements (minimum number of course credits); Special Diploma Option 2 – must fulfill individually designed graduation training plan, which includes annual goals or short-term objectives or benchmarks related to employment and community competencies; must show mastery of competencies in employment and community competencies training plan; this option is NOT available to students who have been identified as visually impaired or speech impaired, unless they also have another identified disability. |

Indiana |

District determined requirements: Certificate of Completion (or similar document designated by the district) |

Kentucky |

Alternative course of study: Alternative High School Diploma – completes alternative course of study |

Louisiana |

Takes alternate assessment based on AAS: Certificate of Achievement – takes LAA1 |

Maryland |

Takes alternate assessment based on AAS: Certificate of Program Completion – student remains in Alt-MSA for duration of schooling |

Nevada |

Meets IEP requirements: Adjusted Diploma – satisfy requirements in IEPs |

New York |

Takes alternate assessment based on AAS: Skills and Achievement Commencement Credential – with specific requirements, including only for students instructed and assessed on alternate performance level, can only be awarded after at least 12 years of school excluding K, credential is NOT considered a regular diploma, credential must be similar in form to diplomas, credential must be issued with a student exit summary of academic achievement and functional performance, if student is less than 21 can still attend public schools without payment of tuition |

North Carolina |

Meets IEP requirements: Graduation Certificate – successfully complete 21 course credits in high school, and pass all requirements of IEP |

Oregon |

Takes alternate assessment based on AAS: Modified Diploma, Extended Diploma, or Alternative Certificate – These diplomas are awarded only to students who have demonstrated the inability to meet the full set of academic content standards even with reasonable modifications and accommodations; Extended diploma awarded only to students who have demonstrated the inability to meet the full set of academic content standards even with reasonable modifications and accommodations and who have a documented history of a medical condition that creates a barrier to achievement, and participate in an alternate assessment or have a serious illness or injury that changes the student’s ability to participate in grade-level activities. |

Rhode Island |

No other documents available: notes that the students in RIAA does not earn a diploma but may participate in graduation ceremonies. Also, there is an IEP Team Assurance of Parental Notification, which requires the IEP team to inform parents of the implications of their child’s participation in the RIAA, including 2. “Beginning with the 2014 graduating class, the RIAA cannot be used to meet the state assessment requirement for receiving a diploma since the RIAA is based on alternate grade level and grade span expectations.” |

South Carolina |

Attendance: Certificate of Attendance (conveyed by district) |

Tennessee |

Meets IEP requirements: Special Education Certificate – awarded to students with disabilities who have (1) satisfactorily completed an IEP, (2) successfully completed a portfolio, and (3) have satisfactory records of attendance and conduct. |

Virginia |

Meets IEP requirements: Special Diploma – available to students with disabilities who complete the requirements of their IEP and who do not meet the requirements for other diplomas (General Achievement Diploma – for students 18 or older who meet Board of Education criteria; GED – for students who complete prescribed programs of studies defined by local school board but who do not qualify for diplomas) |

West Virginia |

Meets IEP requirements: Modified1 Diploma – IEP team decision to work toward AAAs and the student meets these IEP objectives prior to graduation |

Top of Page | Table of Contents

Appendix F

Additional Findings About Graduation Requirements for Students Who Participate in States’ AA-AAS

Table F-1. States that Mentioned Nature of Curriculum

State |

State Responses and Policy Language |

Michigan |

2. Q: If a student is cognitively impaired and was not able to take the MEAP/HST or the new Michigan Merit Exam, is the student still required to complete the Michigan Merit Curriculum to earn a high school diploma? A: Yes. The student must do so either through the general curriculum or the “personal curriculum” defined in the law. The decisions related to a student's educational program should be discussed and determined within the student's Individual Education Program (IEP) process by the IEP Team. A decision to assess the student with the MEAP or MI-Access tests should be a subject of considerable discussion during these meetings and conclusions based on multiple factors (present level of academic achievement and functional performance, the student's stated post school outcomes or desires, student performance on standardized, normative, criterion referenced, summative, formative or curriculum based assessments, etc.). |

New Mexico |

A student must meet the cut score, determined by IEP team, on alternate portfolio to demonstrate competency. Other listed graduation criteria under “Ability” option: Students must participate in Statewide College and Career Readiness Assessment System and District Short Cycle Assessment. The IEP team determines the standard or alternate courses that will make up the student’s program of study. Earn the minimum number of credits required by the district for graduation or be provided equivalent educational opportunities required by the district or charter. Meet all other graduation requirements established by the IEP team. IEP goals and functional curriculum must be based on the State’s content standards with benchmarks and performance standards or the Expanded Grade Band Expectations. |

New York |

5. The credential must be issued together with a summary of the student’s academic achievement and functional performance (Student Exit Summary – see State Developed Model Form Attachment 2) and must include documentation of the student’s: achievement against the Career Development and Occupational Studies (CDOS) learning standards http://www.p12.nysed.gov/cte/cdlearn/; level of academic achievement and independence as measured by NYSAA; skills, strengths, interests; and as appropriate, other achievements and accomplishments. |

North Dakota |

Students must earn the state required minimum number of credits for a regular diploma. Credit for Core content courses maybe achieved through a state approved functional curriculum. |

South Dakota |

Graduation from high school with a regular high school diploma constitutes a change in placement requiring written prior notice in accordance with this article. The instructional program shall be specified on the individual educational program. The individual educational program shall state specifically how the student in need of special education or special education and related services will satisfy the district's graduation requirements. The IEP team may modify the specific units of credit described in § 24:43:11:02. Parents must be informed through the individual educational program process at least one year in advance of the intent to graduate their child upon completion of the individual educational program and to terminate services by graduation. For a student whose eligibility terminates under the above graduation provisions, or due to exceeding the age eligibility for a free appropriate public education, a school district shall provide the student with a summary of the student's academic achievement and functional performance, which shall include recommendations on how to assist the student in meeting the student's postsecondary goals. |

Table F-2. States That Mentioned Parent Knowledge About Diploma Options

State |

State Responses and Policy Language |

Maryland |

Parent Understanding: I have been informed that if my child is determined eligible to participate in the Alt-MSA through the IEP Team Decision-Making Process my child will be: |

Montana |

15. May requirements for granting a diploma be waived for students with disabilities? Each school district shall provide for a waiver of the district established learner outcomes in order to accommodate the needs of special education students. Learner outcomes that are waived must be identified on the student’s IEP. The school district is permitted to waive specific course requirements based on individual student needs and performance levels. Waiver requests shall be considered with respect to age, maturity, interest, and aspirations of the student and shall be in consultation with the student’s parents or guardians. The IEP team must follow local district policy when considering waivers for students with disabilities. |

Ohio |

The third pathway to graduation is for the student with a disability who enters ninth grade on or after July 1, 2010, and before July 1, 2014 to: complete two years of high school as determined by the school;

|

Oklahoma |

Oklahoma offers one high school diploma that is available for all high school students that meet the State minimum graduation requirements. Oklahoma offers two high school education tracks: 1) College Preparatory/Work Ready Curriculum or 2) Core Curriculum Standards. Parents or student have to provide in writing they wish to opt-out of the college preparatory/work ready curriculum. Both tracks meet the State’s requirements for high school graduation and a standard diploma. |

Oregon |

(b) A student may complete the requirements for an extended diploma in less than four years if the parent/guardian or adult student gives consent.

AND |

Rhode Island |

The RIAA cannot be used to meet the state assessment requirement for earning a diploma. Upon determination of eligibility for RIAA, parents and students must be notified that the RIAA cannot be used to meet the state assessment requirement for earning a diploma. |

Table F-3. States that Mentioned Implications for Accountability

State |

State Responses and Policy Language |

New York |

The Board of Education or trustees of a school must (and the principal of a nonpublic school may) issue a Skills and Achievement Commencement Credential to each student with a severe disability in accordance with the following rules.

|

Utah |

Students whose IEP team has determined that his/her participation in state-wide testing is through Utah’s Alternate Assessment (UAA) may earn a high school diploma if all graduation requirements in place at the time of graduation are met. These students, as well as students who receive a Certificate of Completion will be counted as “Other Completers” when calculating graduation rates for LEAs. |

Wisconsin |

School districts are encouraged to issue the same diploma to all students with the transcript documenting the differences in the academic program. However, school districts may develop a policy under s. 118.33 (1) (a), Wis. Stats., to issue multiple types of diplomas. For example, a district might issue a diploma based on 15 credits, a second diploma based on 24 credits, and a diploma based on demonstrating competency in lieu of credits. The label on the diploma may indicate the diploma is the traditional high school diploma, a basic diploma, or an alternative diploma. The label cannot in any way indicate it is a special education diploma. |