Synthesis Report 96States’ Flexibility Waiver Plans for Alternate Assessments Based on Alternate Achievement Standards (AA-AAS)Sheryl S. Lazarus, Lynn M. Edwards, Martha L. Thurlow, and Jennifer R. Hodgson November 2014 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Lazarus, S. S., Edwards, L. M., Thurlow, M. L., & Hodgson, J. R. (2014). States’ flexibility waiver plans for alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS) (Synthesis Report 96). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Table of ContentsExecutive SummaryAll states have alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS) for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. For accountability purposes, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) allows up to 1% of students to be counted as proficient with this assessment option. In 2011 the U.S. Department of Education provided the opportunity fo r states to request flexibility from some of the ESEA accountability requirements. The states’ waiver applications included information that pertained to the AA-AAS, alternate achievement standards, and the students with disabilities who participate in the AA-AAS. This report compiles, analyzes, and summarizes what the states said about the AA-AAS in their applications. Key findings:

The flexibility waivers provided states with an opportunity to develop plans that have the potential to improve student learning and outcomes for all students, including students who participate in the AA-AAS. Some states that belonged to one of the two AA-AAS assessment consortia funded by the Office of Special Education Programs—Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) and National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC)—included information about consortium plans in their applications; several of these states no longer belong to a consortium. There may be a need for these states and the U.S. Department of Education to revisit what the states said about their plans related to the AA-AAS and the students who participate in them to help ensure that the instructional and assessment needs of this population are being met. Top of Page | Table of Contents OverviewThe 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and the 2004 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) require the inclusion of all students, including students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, in state and federal educational accountability systems. Most students with disabilities participate in the regular assessment with or without accommodations. Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities participate in an alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS). States may count up to one percent of students participating in an AA-AAS as proficient for federal accountability purposes. Beginning in 2011, states were allowed to apply for flexibility from some of the ESEA requirements, and states that sought flexibility submitted an application to the federal government. States must provide incentives for districts or schools to increase achievement outcomes for all students, including students from traditionally low-achieving subgroups, so states included plans for improving the assessment and instruction of students who participate in the AA-AAS in their applications. As of May, 2014, 45 states—43 regular states and 2 unique states (District of Columbia, Puerto Rico)—had received approval of their waiver applications for flexibility from ESEA requirements, though Washington recently lost its waiver when the U.S. Department of Education did not grant the state an extension to its waiver due to issues with its educator evaluation system. Also, Kansas, Oregon, and Arizona were placed on high risk status for their waivers. Two additional regular states (Iowa and Wyoming) and one unique state (Bureau of Indian Education) have submitted waiver requests for ESEA flexibility (U.S. Department of Education, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c; U.S. Department of Education, 2014a, 2014b). Information about how states plan to address the needs of students who participate in the AA-AAS is spread across the many waiver applications. To obtain a picture of how the AA-AAS was addressed in the waiver applications, we compiled, analyzed, and summarized the information in the applications about the AA-AAS and the students who participated in them. This report is a companion report to a previously published report (Lazarus, Thurlow, & Edwards, 2013) that analyzed states’ approved waiver requests in terms of their plans to phase out another alternate assessment, the alternate assessment based on modified achievement standards (AA-MAS). Some states with approved flexibility waiver applications have joined either the Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) or the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) consortia, and plan to use the new assessments being developed by the AA-AAS consortium. In many of these states, the applications included a discussion of their involvement in the consortia. Two research questions are addressed in this report:

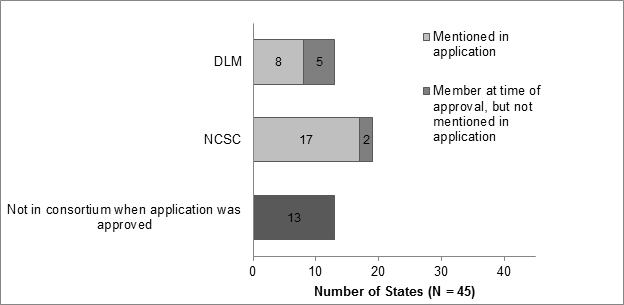

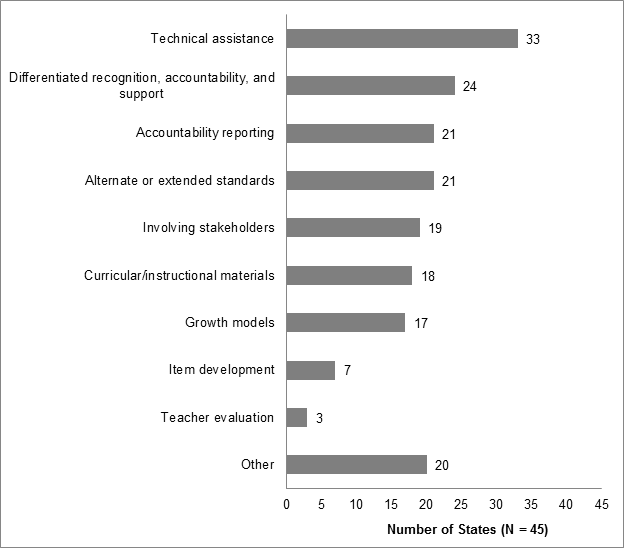

Top of Page | Table of Contents Analysis ProceduresThe approved ESEA waiver applications of the regular states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico that had been approved as of May 6, 2014 were reviewed for this analysis. The applications were downloaded from http://www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/guid/esea-flexibility/index.html (see Appendix A for a list of documents reviewed). Information in each state waiver application was analyzed for information related to one or more of the following topics: (a) the AA-AAS in general; (b) alternate academic achievement standards; and (c) the population of students expected to participate in the AA-AAS. If a state included information about its membership in an AA-AAS assessment consortium (DLM or NCSC), this information was also compiled and summarized. States used various terms to refer to the population of students who participated in the AA-AAS (e.g., students with significant cognitive disabilities, students with severe disabilities, students with profound disabilities). Information in the waiver applications that referred to this population of students using any of these terms was analyzed. Information within a state waiver application that pertained to the AA-AAS, alternate achievement standards, and students with disabilities who participated in this assessment was compiled and then coded. To generate the coding categories, the policies of five states were reviewed. Based on the information found in those policies, themes were identified, and codes were developed. The policies of additional states were then reviewed and coded. When the need for more coding categories was identified, additional codes were added. Previously coded states were then reviewed again to make sure that they should not be coded for the additional coding categories. Top of Page | Table of Contents ResultsResults are presented in two sections. The first section summarizes findings about whether states identified the AA-AAS consortium membership in their waiver applications. The second section addresses specific themes/coding categories related to the AA-AAS that states discussed in their approved waiver applications. States’ Declared AA-AAS Consortium MembershipAs shown in Figure 1, many of the states that received waivers were members of one of the alternate assessment consortia. Some of these states mentioned their consortium membership in their waiver applications—others did not. Of the 13 states in DLM that received waivers, eight states indicated that they were members of the consortium in their flexibility waiver applications and five did not. Seventeen states indicated that they were a member of NCSC in their applications and two states were members of NCSC did not mention it. Fourteen of the states were not in an AA-AAS consortium when their waiver application was approved. Table B1 in Appendix B provides a list of states’ AA-AAS consortia memberships. Figure 1. States’ Consortia Membership Related to the AA-AAS

Note. The numbers in this figure are based on consortia membership at time of waiver application submission.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

State |

DLM |

NCSC |

Not in a consortium when application approved |

||

Mentioned in application |

Member at time of approval, but not mentioned in application |

Mentioned in application |

Member at time of approval, but not mentioned in application |

||

Alabama |

|

|

|

|

X |

Alaska |

|

|

X1 |

|

|

Arizona |

|

|

X |

|

|

Arkansas |

|

|

|

|

X |

Colorado |

|

|

|

|

X3 |

Connecticut |

|

|

X |

|

|

Delaware |

|

|

|

|

X |

District of Columbia |

|

|

X |

|

|

Florida |

|

|

X |

|

|

Georgia |

|

|

|

X1 |

|

Hawaii |

|

|

|

|

X |

Idaho |

|

|

X |

|

|

Illinois |

X |

|

|

|

|

Indiana |

|

|

|

X |

|

Kansas |

X |

|

|

|

|

Kentucky |

|

|

|

|

X |

Louisiana |

|

|

X |

|

|

Maine |

|

|

X |

|

|

Maryland |

|

|

|

|

X |

Massachusetts |

|

|

X |

|

|

Michigan |

X |

|

|

|

|

Minnesota |

|

|

|

|

X |

Mississippi |

X |

|

|

|

|

Missouri |

|

X |

|

|

|

Nevada |

|

|

X1 |

|

|

New Hampshire |

|

|

|

|

X |

New Jersey |

|

X |

|

|

|

New Mexico |

|

|

|

|

X2 |

New York |

|

|

X |

|

|

North Carolina |

|

X |

|

|

|

Ohio |

|

|

|

|

X |

Oklahoma |

X |

|

|

|

|

Oregon |

|

|

X |

|

|

Pennsylvania |

|

|

X1 |

|

|

Puerto Rico |

|

|

|

|

X2 |

Rhode Island |

|

|

X |

|

|

South Carolina |

|

|

X |

|

|

South Dakota |

|

|

X |

|

|

Tennessee |

|

|

X |

|

|

Texas |

|

|

|

|

X |

Utah |

|

X |

|

|

|

Virginia |

|

X |

|

|

|

Washington |

X3 |

|

|

|

|

West Virginia |

X |

|

|

|

|

Wisconsin |

X |

|

|

|

|

No. of States |

8 |

5 |

17 |

2 |

13 |

Note: See Table B2 for specifications and descriptions.

1 Dropped out of NCSC after approval of waiver.

2 Puerto Rico stated it had not joined a consortium but was considering adopting the NCSC alternate assessment.

3 Dropped out of DLM after approval of waiver.

Table B2. Specifications and Descriptions of States’ Assessment GSEG Consortia Membership

State |

Consortia Specifications and Descriptions |

Alaska |

NCSC: Strategies that focus on the needs of specific groups of students are planned. To address the needs of students with disabilities, Alaska has joined the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) consortium, which is developing a new system of supports including assessment, curriculum, instruction and professional development to help students with disabilities graduate high school ready for postsecondary options. NCSC will create a framework that uses scaffolded learning progressions to bring these students toward an understanding of the Alaska new standards. There results with be reviewed with the state’s special education directors at the annual special education director’s training. EED will continue to analyze the learning and accommodation factors necessary to ensure that students with disabilities have the opportunity to access learning content aligned with Alaska’s new standards. EED makes it a priority to help all teachers understand their responsibility to serve these students and to empower teachers by embedding differentiated strategies that benefit students with disabilities, as well as all other students (p. 35). Alaska has joined the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) consortium to address the needs of students with severe cognitive disabilities. Alaska has participated in the Curriculum and Instruction workgroup, the Technology workgroup, and in regularly scheduled Community of Practice meetings with NCSC leadership. Alaska has addressed the following key factors in its work with the NCSC: articulating college and career readiness; defining the construct relative to the Alternate Assessment on Alternate Achievement Standards and the students it serves; developing communicative competence; delivery of professional development; building capacity to deliver professional development; and developing a strong argument for validity. Alaska will continue to coordinate with its qualified mentors, qualified assessors, and school district test coordinators to ensure that expectations are well-understood for students with severe cognitive disabilities as Alaska transitions to the college- and career-ready standards (p. 46). |

Arizona |

NCSC: ADE staff with expertise in Special Education is also engaged in the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) which is an assessment consortium for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Three staff members are on the NCSC work groups (Assessment, Curriculum and Instruction, Professional Development) and one serves on the management team. Arizona is on target for meeting the Year 1 goal by identifying 33 Community of Practice (COP) members who have begun to receive training on the CCSS, the relationship among content and achievement standards, curriculum, assessment, and access to the general curriculum. The COPs will be asked to implement model curricula and assist ADE in providing continued trainings across the state to teachers serving students with significant intellectual disabilities (p. 25). |

Connecticut |

NCSC: In addition to joining SBAC, the CSDE has joined the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) to develop a multistate comprehensive assessment system for students with significant cognitive disabilities. This consortium applies current research-based lessons for alternate assessment based upon alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS) (p. 65). |

District of Columbia |

NCSC: The DC OSSE has joined the assessment consortium with the NCSC and is a member of the Workgroup One Community of Practice. Through this partnership, the DC OSSE will continue to develop performance-level descriptors, claims, focal knowledge, skills, and abilities for mathematics to provide information and guidance about the CCSS. The goal of NCSC is to ensure that students with significant cognitive disabilities achieve higher academic outcomes to prepare them for post-secondary options. The DC OSSE believes in this goal and is excited to be involved with this work (p. 33). |

Florida |

NCSC: Florida also is planning to analyze the learning factors necessary to ensure that students with significant cognitive disabilities have access to the Common Core State Standards at reduced levels of complexity. To accomplish this, Florida is participating with the National Center and State Collaborative General Supervision Enhancement Grant (NCSC GSEG) to define college and career-ready for this population of students and to identify Core Content Connectors to the Common Core State Standards. Florida is currently a partner with 18 other states and four research centers to develop Core Content Connectors for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Once released, curriculum guides and other materials will be provided that will serve as the foundation for classroom instruction (p. 23). |

Idaho |

NCSC: Idaho's involvement in the NCSC as a Tier II state participant, allows Idaho teachers of students with significant cognitive disabilities access to the Common Core State Standards aligned professional development, curriculum and instructional resources pilot tested and refined by the Tier 1 states. Idaho will have access to all NCSC products and materials before broad dissemination by 2015. Specifically, Idaho's |

Illinois |

DLM: Participation in PARCC & DLM Field Test. |

Kansas

|

DLM: Kansas is a member of the Dynamic Learning Maps Alternate Assessment Project (DLM), one of the two consortiums awarded a GSEG grant to develop an alternate assessment in reading and math for students who have significant cognitive disabilities based on the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). Kansas has been a member of this consortium since the group was awarded the grant. Teachers from member states have been involved in developing new Essential Elements (Extended Standards) Achievement Level Descriptors in reading and math. The Common Core Essential Elements (CCSS) are specific statements of the content and skills that are linked to the CCSS grade level specific expectations for students with significant cognitive disabilities (p. 45). |

Louisiana |

NCSC: Louisiana joined the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC), a project led by five centers and 19 states to build an alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards for students with significant cognitive disabilities. In addition to the development of an alternate assessment, NCSC is developing curriculum, instruction, and professional development support for teachers of students with significant cognitive disabilities. The project also involves identifying effective communication strategies for students, the development of material at varying levels of complexity to meet students’ unique learning needs, and accommodation policies appropriate for this population. Louisiana has established a Community of Practice comprised of teachers and district and school administrators who work with this population of students. The group reviews materials and provides feedback as they are developed. The goal of the NCSC project is to ensure that students with significant cognitive disabilities achieve increasingly higher academic outcomes and leave high school ready for post-secondary options (p. 37). |

Maine |

NCSC: Maine is a Tier II Affiliated state in The National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC), a consortium of states developing a new alternate assessment tool for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. In addition to developing an assessment, NCSC is developing aligned curriculum, instruction and professional development for teachers of students with significant cognitive disabilities. As a Tier II state, Maine will have access to curriculum, instruction and professional development opportunities provided by NCSC, as well as providing beta-testing of the assessment instrument (p. 31). |

Massachusetts |

NCSC: We have also been working to analyze and implement the learning and accommodation factors necessary to ensure that students with disabilities will have the opportunity to meet and exceed the college- and career-ready standards. In 2006, ESE published Guides to the Curriculum Frameworks in ELA, Mathematics, Science and Technology/Engineering, and History/Social Science for Students with Disabilities. These will be updated in 2012 to align to the new Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks for ELA/Literacy and Mathematics. This alignment project will be conducted with other states and university research centers through the alternate assessment consortium, the National Center State and Collaborative (NCSC), and will serve as a resource for other states throughout the country (p. 16). |

Michigan |

DLM: Michigan offers assessment alternatives for students with disabilities. MI‐Access is Michigan's alternate assessment system, designed for students with severe cognitive impairments whose IEP (Individualized Educational Program) Team has determined that MEAP or MEAP‐Access assessment, even with accommodations, would not be appropriate. MI‐Access satisfies federal law requiring that all students with disabilities be assessed at the state level. Looking ahead to assessments based on the CCSS, Michigan has joined the Dynamic Learning Maps Consortium which is developing an assessment based on the Common Core Essential Elements (CCEEs). The CCEEs were created by the member states in the DLM Consortium. Special education teachers are currently transitioning from Michigan’s extended grade level expectations to the CCEEs (p. 38). |

Mississippi |

DLM: Mississippi is a governing member of The Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) Alternate Assessment System Consortium. DLM is a multi-state consortium awarded a grant by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) to develop a new alternative assessment system. DLM is led by The Center for Educational Testing and Evaluation (CETE) and includes experts from a wide range of assessment fields as well as key partners, such as The Arc, the University of Kansas, Center for Literacy and Disability Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and Edvantia (p. 45). |

Nevada

|

NCSC: Nevada’s students with significant cognitive disabilities need increased support to meet the rigorous expectations of the CCSS. To facilitate this outcome, Nevada has joined the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) General Supervision Enhancement Grant (GSEG). The NCSC GSEG is a multi-state project drawing on a ten-year research base. Its long-term goal is to ensure that students with significant cognitive disabilities achieve increasingly higher academic outcomes and leave high school ready for post‐secondary options. The NCSC is developing a full system intended to support educators in implementing college- and career-ready standards among students with disabilities. The system will include a summative assessment, curriculum resources and Scripted Lessons aligned to the CCSS, as well as formative assessment tools and strategies, professional development on appropriate interim uses of data for progress monitoring, and management systems to ease the burdens of administration and documentation (p. 34). For the development of Alternate Assessments aligned to Alternate Achievement Standards (AAAAS) aligned to the CCSS, Nevada is a member of the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) General Supervision Enhancement Grant (GSEG). Assessments designed under the work of this consortium will serve as alternate assessments to the SBAC, with Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) as a partner in the AA-AAS project. The Dynamic Learning Maps Alternate Assessment System Consortium (DLM) is a group of 13 states dedicated to the development of an alternative assessment system. The consortium includes the States of Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. DLM is led by the Center for Educational Testing and Evaluation (CETE).The primary purpose of the NCSG-GSEG consortium is to build an assessment system based on research-based understanding of: |

New York

|

NCSC: For students with disabilities who take New York State's Alternate Assessment (NYSAA), new Alternate Achievement Standards are under development and will be introduced in conjunction with the new assessments. New York State is also one of 19 state partners in the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) Project, which is working to develop a comprehensive assessment system for students with significant cognitive disabilities by 2014-15. An initial part of this process was an analysis of the Common Core to determine the skills required by students with cognitive disabilities. Based on this analysis, NCSC is building a comprehensive system that will include curriculum and instructional modules, comprehensive professional development and an alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS) that were developed from the best practice-oriented and psychometric research available. Statewide implementation is pending Board of Regents approval. Since NCSC's Alternate Assessment will not be developed until 2014-15, the state is using this process to inform an alignment of our current Alternate Assessment with the new Common Core aligned Alternate Achievement Standards. The new Alternate Achievement Standards are under development and will be introduced in conjunction with the new assessments. The new Alternate Assessments will be implemented on a rolling schedule, with each series of content area assessments to be implemented one year after the general education equivalent (p. 35-36). |

Oklahoma |

DLM: Oklahoma is also participating in the Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM), a consortium funded to assist states in developing assessments for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. The DLM consortium is in the process of developing alternate academic achievement standards to align with CCSS (p. 28). |

Oregon |

NCSC: Oregon has recently partnered with the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) in the development of an alternate assessment. Each of these consortia is dedicated not only to developing a fully accessible assessment based in CCSS, but also to developing an array of formative assessment tools and approaches intended to improve instruction and ensure that students are accessing the content (p. 39). |

Pennsylvania

|

NCSC: For students with significant cognitive disabilities, Pennsylvania participates in National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC). As a NCSC state partner, Pennsylvania is in the process of implementing the materials and resources developed by NCSC as an instructional model, aligned to Common Core. These resources will support educators as they design and implement appropriate instruction that address content and skill expectation aligned to PA Common Core Standards. All NCSC curriculum and instruction assets will be posted in SAS; this includes content modules and element cards, curriculum resource guides, instructional units and scripted lessons, and core content connectors. Although currently complete for Mathematics, English Language Arts—when available - will also be posted and available on the SAS portal. These high quality materials will help to prepare students with the most cognitive disabilities for college and career ready opportunities post high school (p. 25). |

Puerto Rico

|

No Consortia specified: Unlike other States, PRDE’s language of instruction is Spanish so we cannot simply join one of the major consortia; although they may be including some Spanish language versions of tests, these are (a) designed as accommodations rather than core tests and (b) unlikely to reflect the linguistic and cultural considerations that are key to valid assessment of content knowledge in Puerto Rico. Thus, we must continue to develop PRDE’s own assessments that maintain a link with common notions of college and career readiness yet also allow PRDE’s students to demonstrate what they know and can do. At the June TAC meeting we will discuss: PRDE’s next generation of assessments, changes to current assessments to increase rigor and prepare students and teachers for the next generation of assessments, best assessment alternatives to measure learning gains for students with significant cognitive impairments, the evaluation of non-tested grades, and the development and implementation of formative evaluation for non-tested subjects among other issues. The expected outcome of the meeting is to establish a work agenda to develop the next generation of assessments and alternative assessments in line with ESEA Flexibility guidelines (p. 63). Alternative Assessments: Furthermore, PRDE is considering adopting the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) alternate assessment system that is currently being developed by the University of Minnesota under a grant from the Office of Special Education Programs at the Department. This would further enrich our approach to ensuring that all students are held to a common set of high academic expectations. This system is not presently being developed in Spanish. PRDE recognizes that there is significant cost associated with the translation of the NCSC assessment into Spanish and does not have the fiscal resources to cover the full expense. However, PRDE’s experience with the WIDA SALSA grant suggests to PRDE that other NCSC states will be interested in creating a Spanish-language version of this system and we could mutually-benefit from collaboration with other entities on Spanish versions of the assessment and the curriculum. Additionally, PRDE will consider the possibility of contributing some of its 1116 funds to this endeavor in the near future and look to States such as California and New Mexico to identify effective strategies for transitioning to this new assessment. PRDE’s adoption of the NCSC alternate assessment system will, thus, be contingent on 1) the degree to which the NCSC assessment is proven to be a valid assessment of PRDE’s enacted curriculum [describe when PRDE would conduct such an analysis], 2) the availability of a validated Spanish version of the assessment, and 3) the availability of funds to support implementation. While Puerto Rico’s Secretary of Education has the authority to execute the formal adoption of the NCSC alternate assessments, this process involves various stakeholders for successful adoption and implementation If PRDE decides not to adopt this assessment, it realizes that it will need to either develop its own alternate assessment or keep its current assessment. PRDE believes that the most realistic option will be to maintain its current process of using a portfolio. The portfolio will be based on the new college and career ready standards that will be adopted. The processes used to revise the PPEA would be modeled after the successful practices PRDE has used in the past (see pages 46, 58 and 60 for additional detail about the current PPEA). PRDE’s goal is to maximize these students access to the general curriculum by providing them with a high quality standard based instruction linked to the 2007 content standards and grade-level expectations and ensure that students will graduate from high school ready for college and careers. All students with disabilities must have access to the same curriculum as their peers, age appropriate materials, and an engaging academic experience (pp. 45-46). |

Rhode Island |

NCSC: Finally, as part of our Comprehensive Assessment System, Rhode Island is participating in several national consortia, which are or will implement common summative assessments. Rhode Island is a governing member in the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) consortium, a member of the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) consortium, and a member of the World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) Consortium. Rhode Island is taking an active role in each consortium to ensure that the assessments are rigorous, of high quality, and valid and reliable measurements of the student population the assessment is designed to assess. The NCSC is developing a comprehensive system that addresses the curriculum, instruction, and assessment needs of students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. The NCSC is developing a summative assessment in English language arts and Mathematics in grades 3 through 8 and in one grade level in high school. The NCSC is designing this summative assessment to support valid inferences about student achievement on the assessed domains. The NCSC will use technology to deliver assessments with appropriate accommodations, to score, and to report on the assessments. In addition, the NCSC is developing curriculum and instruction tools, and the NCSC is developing state-level communities of practice. These resources will support educators as they design and implement appropriate instruction that addresses content and skill expectations aligned with the Common Core State Standards (CCSS); these resources will also help prepare students with the most significant cognitive disabilities for postsecondary life (p. 29-30). |

South Carolina |

NCSC: South Carolina is working with the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC) to develop an alternative assessment on alternate achievement standards aligned to the CCSS. South Carolina is a partner state in the NCSC, a consortia funded by the US Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs General Supervision Enhancement Grant to develop a system of support, including assessment, curriculum, instruction, and professional development, to ensure that students with significant cognitive disabilities graduate from high school ready for post-secondary options (p. 29). |

South Dakota

|

NCSC: Several secondary strategies that focus on the needs of specific groups of students are also under way or planned. To address the needs of students with disabilities, South Dakota has joined the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC), a consortium of 19 states which intends to develop a new system of supports including assessment, curriculum, instruction and professional development to help students with disabilities graduate high school ready for postsecondary options. NCSC will create a framework aligned with the Common Core standards that uses scaffolded learning progressions to bring these students towards an understanding of the Common Core concepts. The basis of these scaffolded learning progressions, known as Common Core Connectors, will be made available to states for the 2012-13 school year, and will be followed by lesson plans on key Common Core concepts. As a partner state, South Dakota has convened a 30-member community of practitioners—including LEA special education supervisors, special education teachers, SD DOE staff, and other stakeholders (e.g. advocacy groups)—which participates in the NCSC work group focusing on professional development. Additionally, the state will have access to the work done by other states in the areas of assessment, curriculum and instruction. After NCSC completes its work by the 2014-15 school year, South Dakota will adopt the new assessment system and related materials (p. 21). For students with significant cognitive disabilities who require an alternate assessment, South Dakota is a member of the National Center and State Collaborative General Supervision Enhancement Grant consortium. Through the grant project, an alternate assessment aligned to the Common Core State Standards will be developed for a census pilot and administered in the 2013-2014 school year. South Dakota plans to use this assessment for accountability purposes in grades 3-8 and 11. Until that time, the state will continue to use its Dakota STEP-A assessment at grades 3-8 and 11 (p. 30). |

Tennessee |

NCSC: To that end, Tennessee has joined, along with 18 other states, the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC; see http://www.ncscpartners.org), a consortium which intends to develop a new system of supports—including assessment, curriculum, instruction, and PD to help them graduate high school ready for postsecondary options (p. 24). |

Washington |

DLM: Washington will move to an alternate assessment of the Common Core State Standards in 2014–15. Washington is an active participant in the Dynamic Learning Maps assessment consortium and likely will utilize the DLM assessments for Mathematics and English Language Arts for implementation in 2014–15. As with the general assessment, the ELA consortia assessment will mean Washington will eliminate the Writing WAAS-Portfolio. Science will continue to be assessed through the WAAS-Portfolio until the Next Generation Science Standards are available and a new assessment is developed to assess those standards (p. 118). |

West Virginia |

DLM: We also provide plans to continue and accelerate our involvement as a governing state on the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium and as a member of the Dynamic Learning Maps Alternate Assessment Consortium to prepare for full |

Wisconsin

|

DLM: One component of the Every Child a Graduate vision (http://dpi.wi.gov/sprntdnt |

Table B3. States’ Criteria On or Related to the AA-AAS

State |

Criteria |

|||||||||

Technical assistance |

Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support |

Accountability reporting |

Alternate or extended standards |

Involving stakeholders |

Curricular/ instructional materials |

Growth models |

Item development |

Teacher evaluation |

Other criteria (see Table B4 for specs) |

|

Alabama |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

Alaska |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

Arizona |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Arkansas |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

Colorado |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

Connecticut |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

District of Columbia |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Delaware |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

Florida |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Georgia |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hawaii |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Idaho |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

Illinois |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

Indiana |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Kansas |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

Kentucky |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

Louisiana |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

Maine |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maryland |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

Massachusetts |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Michigan |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

Minnesota |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

Mississippi |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Missouri |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Nevada |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

New Hampshire |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

New Jersey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

New Mexico |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

New York |

X |

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

North Carolina |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

Ohio |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Oklahoma |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

Oregon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Pennsylvania |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

Puerto Rico |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

Rhode Island |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

South Carolina |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

South Dakota |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Tennessee |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Texas |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Utah |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

Virginia |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

Washington |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

West Virginia |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

X |

Wisconsin |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

No. of States |

33 |

24 |

21 |

21 |

19 |

18 |

17 |

7 |

3 |

20 |

Note. See Table B4 for specifications and descriptions.

Table B4. Specifications and Descriptions of States’ Criteria On or Related to the AA-AAS

State |

Criteria Specifications and Descriptions |

Alabama

|

Technical assistance: Teachers of students with significant cognitive disabilities will receive regional training on the new Alabama Extended Standards once they are released (p. 32). Professional Development for New ELA and Math Extended Standards (p. 47). Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: Determination of Torchbearer Reward Schools, Fall of 2013: Must be among the top 20% band of the state using proficiency of ARMT+, AHSGE, and Alabama Alternate Assessment from 2012-13 for Level III and for Level IV (p. 73). Accountability reporting: The AAA will continue to be used in the accountability model for the applicable grades and subjects (p. 47-48). Alternate or extended standards: The Alabama Extended Standards for students taking the Alabama Alternate Assessment are currently under revision to align with the new general education standards for Mathematics and English Language Arts (p. 32) ALSDE staff members from assessment and special education are working to revise the Alabama Extended Standards and the Alabama Alternate Assessment (AAA). Plans are to have the Alabama Extended Standards for mathematics and ELA developed by the spring of 2013 for optional implementation during 2013-14 and required implementation of the standards for both mathematics and ELA during 2014-15. Since the general education science standards are currently under revision and due to be adopted in March 2013 with implementation in fall of 2015, extended standards for science will begin revision immediately following the March 2013 adoption of general standards with implementation of extended standards beginning 2015-2016 with optional implementation for 2014-2015, just as the regular standards are scheduled to be implemented. The Alabama Alternate Assessment will be revised to reflect the new Alabama Extended Standards in ELA and mathematics for implementation in the spring of 2015. Science will follow with implementation in the spring of 2016. New assessments will be as follows:

Other: In addition, Alternate ACCESS for ELLs will be administered in Alabama for the first time this school year. This assessment was developed through an Enhanced Assessment Grant (EAG) and is administered to the most severely, cognitively disabled EL students (p. 45). |

Alaska

|

Technical assistance: With the development of the new college- and career-ready standards, the current assessment measures for student with disabilities may require additional supports and considerations. The State’s current assessment procedures have very specific guidelines for accommodations, modifications, and alternate assessments. EED (Alaska Department of Education & Early Development) makes available to school districts training and support to all teachers and administrators to ensure students have appropriate measures in place for assessment under the college- and career-ready standards (p. 28). EED will continue to analyze the learning and accommodation factors necessary to ensure that students with disabilities have the opportunity to access learning content aligned with Alaska’s new standards. EED makes it a priority to help all teachers understand their responsibility to serve these students and to empower teachers by embedding differentiated strategies that benefit students with disabilities, as well as all other students (p. 35). Alaska will continue to coordinate with its qualified mentors, qualified assessors, and school district test coordinators to ensure that expectations are well-understood for students with severe cognitive disabilities as Alaska transitions to the college- and career-ready standards (p. 46). Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: In addition, schools are still required to set and meet AMOs for each subgroup. Whether a school has met its AMOs for subgroups will be included as a factor in determining whether a school is a focus or a priority school. This is further evidence that the system is designed to close achievement gaps (p. 36). Because Alaska has chosen to waive the requirement to report schools as making Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP), the following requirements in the currently approved Accountability Workbook will apply to reporting whether schools meet the AMO targets: 1% cap for students with disabilities who take the alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards will still apply (p. 74). Accountability reporting: The new recognition, accountability, and support system proposed by this application will significantly increase the focus and attention on the issue of subgroup performance over what was occurring under Annual Yearly Progress (AYP). This is because the high-stakes nature of AYP required that we have a minimum N and a confidence interval regarding whether a school or district met AYP for that subgroup. In contrast, inclusion of a point value in an index is not itself a high-stakes matter, even though the overall index point value is high stakes. This allows Alaska to relax the minimum N for inclusion of subgroups into the index to five. The impact of this change will be significant because many of our schools were small to medium- sized schools that were affected by the minimum N/confidence interval for subgroups. In reviewing the proposed Alaska School Performance Index (ASPI) model, the Governor’s Council on Disabilities and Special Education provided comment in favor of the increased accountability that the minimum N of five will bring to the students with disabilities subgroup. Furthermore, in order to maintain high accountability for subgroups, Alaska has resisted requests to consider a super subgroup or to eliminate duplication for students in more than one subgroup. Thus, the system is designed to close achievement gaps (p. 35-36). Involving stakeholders: As a NCSC partner state, Alaska has convened stakeholders—including district special education supervisors, special education teachers, EED staff, and advocacy groups—to participate in the focus on professional development. Additionally, Alaska will have access to work done by other states in assessment, curriculum and instruction (p. 35). Other: WIDA and EED worked collaboratively to provide live webinars to be recorded and posted to WIDA’s website (all are posted here: http://www.wida.us/downloadLibrary.aspx). The specific webinars are listed below: Alternate ACCESS for ELLs live webinar—December 18, 2012. (p. 32-33) Alaska recognizes the role of teacher preparation programs in developing the next generation of educators. Alaska has taken specific steps to bring higher education into the transition to Alaska’s new standards. Representatives from Alaska’s public universities’ teacher preparation programs are engaged in a standards professional development series for teachers. These instructors will incorporate the standards and associated instructional approaches into their pre-service programs (p. 36). |

Arizona

|

Technical assistance: Arizona is on target for meeting the Year 1 goal by identifying 33 Community of Practice (COP) members who have begun to receive training on the CCSS, the relationship among content and achievement standards, curriculum, assessment, and access to the general curriculum. The COPs will be asked to implement model curricula and assist ADE in providing continued trainings across the state to teachers serving students with significant intellectual disabilities (p. 25). Our long-term goal is to ensure that students with significant cognitive disabilities achieve increasingly higher academic outcomes and leave high school ready for post-secondary options. A well-designed summative assessment alone is insufficient to achieve that goal. Thus, NCSC is developing a full system intended to support educators, which includes formative assessment tools and strategies, professional development on appropriate interim uses of data for progress monitoring, and management systems to ease the burdens of administration and documentation. All partners share a commitment to the research-to-practice focus of the project and the development of a comprehensive model of curriculum, instruction, assessment, and supportive professional development. These supports will improve the alignment of the entire system and strengthen the validity of inferences of the system of assessments (p. 195). Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who take the alternate assessment (AIMS A) will Accountability reporting: Arizona will incorporate the same process used under IDEA to identify any LEA who exceeds the 1.0 percent cap into the state's A-F Letter Grade System. LEAs will be notified if they have exceeded the 1.0 percent cap and which proficient scores will count as non-proficient at schools in the LEA. This determination is based on the additional data collected regarding the eligibility determination process for student(s) assessed with AIMS A (IEP and MET). ADE will assist any LEA who meets the criteria in 34 CFR Sect 200.13(c)(5)(1) (i.e., small LEA, LEA with special schools) in filing an appeal for an exception to the 1.0 percent cap Alternate or Extended Standards: Arizona is the funding state agency for Project Longitudinal Examination of Alternate Assessment Progressions (LEAAP). LEAAP is an analysis of curricular progressions and student performance across grades on states' alternate assessments based on alternate academic achievement standards (AA-AAAS) for students with significant cognitive disabilities. LEAAP will allow states to examine student progress over time - in both performance and skills assessed. Western Carolina University manages all project activities with oversight by the ADE and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. This project also includes partners from Maryland, South Dakota, and Wyoming. LEAAP will inform states' future improvements in AA-AAAS systems, including accessibility and validity. The results of the analysis will provide detailed information about Arizona's current Arizona's Instrument to Measure Standards Alternate (AIMS A) and the relationship between the Common Core Standards and Arizona alternate academic standards. The results will further provide guidance on how to further support teacher's transition from using the alternate standards to the Common Core standards for instructional purposes. (p. 25) Involving stakeholders: We are writing in support of the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) collaborative proposal for the General Supervision Enhancement Grants: Alternate Academic Achievement Standards. We look forward to working with our colleagues in many states and the organizational partners at NCEO, the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment (NCIEA), the Universities of Kentucky (UKY) and North Carolina, Charlotte (UNCC), and edCount LLC on this important topic. The Theory of Action underlying the proposed work plan is consistent with the goals and purposes of our state assessment system, and we believe our joint efforts will increase the achievement and quality of outcomes for students with significant cognitive disabilities in Arizona. You and your collaborative partners clearly have a long history of working effectively with states on inclusive assessment and accountability systems. In this project, Arizona will commit to our joint work in the following ways: Curricular/Instructional materials: The COPs will be asked to implement model curricula and assist ADE in providing continued trainings across the state to teachers serving students with significant intellectual disabilities (p. 25). Item Development: Finally, information related to the accessibility of items will also be included in the final analysis of AIMS A items (p. 25). |

Arkansas

|

Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: The annual school performance data from the Arkansas assessments required under section Accountability reporting: Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities participate in the required assessments by completing an alternate portfolio assessment approved by USDE for use in NCLB accountability. Arkansas’ Other: Arkansas’s Comprehensive Testing, Assessment and Accountability Program (ACTAAP) includes criterion referenced tests (CRTs) for all students in math and literacy at Grades 3 through 8 and Grades 5 and 7 for science. At the high school level, Arkansas requires all students to complete End of Course Exams in Algebra, Geometry and Biology, as well as a Grade 11 Literacy Exam. SWD and ELs participate in these required assessments with or without accommodations as specified in their Individual Education Plans (IEP) or English Language Acquisition Plans (ELAP). Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities participate in the required assessments by completing an alternate portfolio assessment approved by USDE for use in NCLB accountability. Arkansas’s approved Adequate Yearly Progress Workbook specifies the use of math and literacy exams in Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) determinations for identifying schools’ and districts’ School Improvement status (p. 40). |

Colorado

|

Technical assistance: CDE provides online classes, professional development, and instructional tools that target the needs of students with disabilities. To help build local capacity, most utilize a trainer of trainer model. Below is a listing of some of the professional development opportunities. All of the following are intended for both general education and special education teachers (p. 37). Regional development of model autism and significant support needs programs.This project is a collaborative effort to implement the RtI process to build quality programs for students with SSN and ASD. Using both SSN and Autism Quality Indicators as guidelines and to collect data measuring current program practices, baselines and target goals will be set. We began with 2 administrative units across the state in various settings. Year 1 (09-10) SSN sites include Adams 12 (Metro) and Mountain BOCES (Western Region). For Year 2 (10-11) we will expand the project in these AUs to include preschool and MS programs and bringing on 2 more AUs to develop model elementary programs (p. 38). Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: The Achievement indicator on the School and District Performance Framework reports reflect how a school/district’s students are doing at meeting the state’s proficiency goal: the percentage of students proficient or advanced on Colorado’s standardized assessments. (Note that for AYP purposes, Colorado is approved to use partially proficient, proficient and advanced scores. The state system raises the bar to only include proficient and advanced). Academic Achievement indicators include results from CSAP (reading, math and writing given in grades 3-10; science given in grades 5, 8, 10), CSAPA (the alternate CSAP given to students with the most significant cognitive disabilities), and CSAP Lectura/Escritura (the Spanish versions of the reading and writing CSAP, for which English Language Learners in grades 3 and 4 may be eligible) (p. 57). Alternate or extended standards: Additionally, CDE has designed and adopted alternate achievement standards in mathematics, science, social studies, and reading, writing, and communicating for students with significant cognitive disabilities under section 602(3) of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (p. 26). Growth models: The state’s alternate assessment (CSAPA) and the third and fourth grade Spanish version (Escritura) are used only in Academic Achievement, as the state does not calculate growth on the alternate assessment.(p. 71). Other: Additionally, CDE has designed and adopted alternate achievement standards in mathematics, science, social studies, and reading, writing, and communicating |

Connecticut

|

Technical Assistance: The CSDE’s Bureau of Assessment content area experts work directly with consortium management through monthly conference calls and webinars. They also participate in one of the work groups to develop professional development associated with the project. Activities have included the following: Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: Students participating in the CMT/CAPT MAS or the Skills Checklist will be included in the SPI, DPI, and CPI. Students who score at the Independent level on the Skills Checklist will be factored into the SPI as 1.0, students who score at the Proficient level will be assigned 0.67, and the students who score Basic will be assigned 0.33 (pp. 95-96). For the purpose of accountability, at the district level, the number of students who score at the Independent level on the CMT/CAPT Skills Checklist shall not exceed 1% of all students in the grades tested. Additionally, the number of student who score at the Goal level on the CMT/CAPT MAS shall not exceed 2% percent of all students in the grades tested unless scores on the CMT/CAPT Skills Checklist at the Independent level do not reach the 1% cap. The scores of the students who exceed the percentage cap, at the district level, will be factored into the DPI as Basic (p. 96). Involving stakeholders: The CSDE’s Bureau of Student Assessment content area experts participated in the CCSSO SCASS Assessing Special Education Students (ASES) group. The work groups and discussions have focused on the implementation of the CCSS for students with special needs. One of the outcomes of these discussions was a summit for students with disabilities and Common Core college and career readiness held in December 2011. Steering committee members for both ASES and the summit included one CSDE content area expert. Participation in these activities has provided opportunities for the CSDE’s Bureau of Assessment content area experts, in conjunction with the CSDE’s stakeholders, to make informed decisions and to influence the development of the new assessment system for students with significant cognitive disabilities (p. 65). |

Delaware

|

Technical assistance: Professional development related to the Grade Band Extensions (GBEs) began in the fall of 2011 for educators, related service personnel, and administrators serving students with significant cognitive disabilities. Three phases of training are scheduled across the 2011- 2012 school year. Phase I includes an overview of the ELA and Mathematics GBEs and is available in-person or on-line. Phase II provides a more in-depth workshop on use of the GBEs for instruction targeting academics and embedding life skills, vocational training and other access skills as needed by individual students. Phase III professional development utilizes the coaching model to provide individualized support to teachers and school staff to meaningfully apply the GBEs in lessons and create adapted materials to provide access to the general education curriculum. Delaware is committed to providing the supports necessary for all school staff to successfully implement the CCSS including the GBEs (p. 26). Phase III professional development utilizes the coaching model to provide individualized support to teachers and school staff to meaningfully apply the GBEs in lessons and create adapted materials to provide access to the general education curriculum (p. 26). Delaware is a strong proponent of Universal Design for Learning and is partnering with the Delaware Assistive Technology Initiative (DATI) from the University of Delaware to offer professional development (p. 39). The Development Coach spends three or more hours a week in each building to which he or she is assigned working with the school leader in activities such as reviewing formative assessments, co-observing and debriefing observations, observing and providing feedback after pre and post conferences, conducting walk-throughs, and examining artifacts of practice. The Development Coach will also work with LEA level staff to ensure collaboration and alignment with LEA goals and initiatives. A specially designated Development Coach has been identified to work with Administrators in special schools with the most significantly challenged students (students taking the DCASAlt) (p. 124). Accountability reporting: The DCAS—Alt1 is designed to measure the performance of a small subpopulation of students with significant cognitive disabilities against the Delaware Content Standards Grade Band Extensions (approximately 1% of the total student population and 10% of the total number of students with disabilities). Delaware has consistently had rigorous participation criteria and has been able to keep the total percent of students participating in this alternate assessment below 1%. Alternate or Extended Standards: The DCAS—Alt1 is designed to measure the performance of a small subpopulation of students with significant cognitive disabilities against the Delaware Content Standards Grade Band Extensions (approximately 1% of the total student population and 10% of the total number of students with disabilities). After the CCSS were adopted in August 2010, Delaware began the work of creating Grade Band Extensions (GBEs) for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities participating in the alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards. The GBEs were developed through collaboration of special educators, general educators, and related service personnel. In addition, multiple review panels including school administrators, content specialists as well as family and community members reviewed and recommended revisions prior to the State Board adoption of the extensions. English Language Arts and Mathematics GBEs aligned to the CCSS were adopted in May 2011 and Science and Social Studies GBEs aligned to the Delaware Recommended Curriculum were adopted in February 2012. The GBEs provide rigorous standards for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities and are the basis for the new DCAS-Alt1 assessment (p. 25). The DCAS-Alt1 (Delaware’s Alternate Assessment based on Alternate Achievement Standards) conducted standard setting during the summer of 2011. The goals of DCAS-Alt1 are to (1) provide valid and reliable scores for student’s achievement toward the Grade Band Extensions (based on Common Core State Standards) and (2) set targets that are as rigorous of those for their non-disabled peers. Because there is not a national assessment in which to align scores to for the DCAS-Alt1, educators and community members on the Standard Setting Panels reviewed the Achievement Standards established for the DCAS to assist in the decision making process for the DCAS-Atl1. In August of 2011 the State Board approved the equally rigorous Achievement Standards established by the Standard Setting panels (p. 48). Involving stakeholders: After the CCSS were adopted in August 2010, Delaware began the work of creating Grade Band Extensions (GBEs) for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities participating in the alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards. The GBEs were developed through collaboration of special educators, general educators, and related service personnel (p. 48). Curricular/instructional materials: The purpose of the Delaware Comprehensive Assessment System Alternate Assessment (DCAS-Alt1) is to maximize access to the general education curriculum for students with significant cognitive disabilities, ensure that all students with disabilities are included in Delaware’s statewide assessment and accountability programs, and direct instruction in the classroom by providing important pedagogical expectations and data that guide classroom decisions. The DCAS—Alt1 is only for those students with documented significant cognitive disabilities and adaptive behavior deficits who require extensive support across multiple settings (such as home, school, and community) (p. 39). Other: There has been a great deal of work on the Student Improvement (Component 5) of the evaluation system. The following provides highlights around this component. The new regulations that were adopted in January 2010 for 106A and 107A require that Component 5 of the DPAS II evaluation system have “multiple” measures that are rigorous and comparable across schools, LEAs, or the state. These measures could include student’s score on the Delaware Comprehensive |

District of Columbia

|

Technical assistance: Once New Century Learning Consortiums (NCLC) releases the Learning Progressions, the DC OSSE will work to adopt these progressions; it also plans to facilitate teacher and educator professional development that will show IEP teams how to link curriculum and intervention resources to ensure standards progression throughout the school year for all students. Additionally, through this consortium, the DC OSSE is examining how the definition of college- and career-readiness applies to special-needs populations. The District of Columbia currently has a Learning Progressions Community of Practice (LPCoP) consisting of approximately 20 individuals. They include general and special education teachers as well as technical assistance providers to ensure that curricular, instructional, and professional development modules developed by NCSC are practical and feasible. The LPCoP receives training on the CCSS, the relationship between content and achievement standards, curriculum, assessment, and universal access to the general curriculum. Curricular/instructional materials: The DC OSSE has and will continue to analyze the factors needing to be addressed to prepare teachers of students with disabilities participating in the alternate assessment with the goal of successfully preparing these students for participation in assessments aligned to CCSS. For special education students in the 1 percent group (students taking the DC CAS Alternate test), it is most important that current entry points are aligned to the CCSS so that teachers can differentiate instruction according to an individual student’s starting point and allow students to set challenging but achievable academic goals. These entry points are used to guide the evidence-based portfolio assessment the DC OSSE uses for these students. The DC OSSE has currently aligned the DC CAS Alt Entry Points to the CCSS for ELA in preparation for this year’s administration (p. 32-33). |

Florida |

Technical assistance: Florida is currently a partner with 18 other states and four Alternate or extended standards: Florida also is planning to analyze the learning factors necessary to ensure that students with significant cognitive disabilities have access to the Common Core State Standards at reduced levels of complexity. To accomplish this, Florida is participating with the National Center and State Collaborative General Supervision Enhancement Grant (NCSC GSEG) to define college and career-ready for this population of students and to identify Core Content Connectors to the Common Core State Standards. Florida is currently a partner with 18 other states and four research centers to develop Core Content Connectors for students with significant cognitive disabilities. Once released, curriculum guides and other materials will be provided that will serve as the foundation for classroom instruction. Again, these activities will begin at primary grade levels so that all students will be accessing the standards on the same schedule (see below) (p. 23-24). Curricular/instructional materials: Access Courses are for students with significant cognitive disabilities that receive instruction on Next Generation Sunshine State Standards Access Points (p. 30). |

Georgia |

Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: At the school level, aggregate achievement results for all subgroups based on 2010-2011 assessment data for all End-of-Course Tests (EOCTs), all Criterion Referenced Competency Tests (CRCTs), all Criterion Referenced Competency Tests - Modified (CRCT-M), and all Georgia Alternate Assessments (GAAs). For a group (All Students as well as the remaining nine (9) traditional subgroups) to be considered in the calculations, the group must meet the minimum N size of 30 where each member of the group has a valid assessment for each content area (p. 79). |

Hawaii |

Growth Models: The small subset of students with the most severe cognitive disabilities that take the Hawaii State Alternate Assessment are not included in the growth model calculation, as the score scales are not comparable (p. 63). |

Idaho

|

Technical assistance: Idaho will also look to recruit individual districts which can support district-wide collaboration regarding the NCSC professional development, curricular, instructional and assessment tools provided. Participating cohorts and/or districts will also be asked for input on alternate assessment decisions and will be utilized in delivering regional trainings once the NCSC alternate assessment has been developed (p. 47-48). For students with disabilities (SWDs), ISDE provides training and coaching regarding how to best support these students. The ISDE makes sure schools and districts have the support and expertise they need to best meet the needs of their students. For example, if a school in the OneStar category needs support with SWDs, the Idaho Building Capacity Project targets Capacity Builders whose area of expertise is in Special Education for that school. Or, for example, if training in such things as secondary transitions, identification of specific learning disabilities, or supporting the instructional needs of students with significant cognitive impairments is needed, schools are connected with experts at ISDE or institutions of higher Differentiated recognition, accountability, and support: The achievement metric measures school and district performance toward the academic standards assessed on the Idaho Standards Achievement Tests (ISAT) and alternate (ISAT-Alt) in reading, language usage, and mathematics. The determination is based on the percentage of Involving stakeholders: Specifically, Idaho's involvement as a Tier II state is to provide feedback on usability and outcomes of NCSC provided tools and protocols. Idaho will look to recruit a minimum of one to two cohorts, consisting of two to three teachers of students with significant cognitive disabilities who administer the ISAT-Alt, in each of our six state regions (p. 47); SDE will use NCSC professional development, Curricular/instructional materials: Idaho will also look to recruit individual districts which can support district-wide collaboration regarding the NCSC professional development, curricular, instructional and assessment tools provided (p. 47-48). |

Illinois |

Other: Throughout this transition period, ISBE also remains committed to its participation in PARCC, new ELL assessments through the WIDA consortium, a new alternate assessment aligned to the Common Core State Standards, and the Next Generation Science Standards (and subsequent assessment development). As such, Illinois will better prepare students for college and careers as these changes will drive instructional decisions; educators, students, and parents will be equipped with valuable information about student performance and readiness for college and careers; and schools and school districts will be held accountable for their preparation of students for college and careers. |

Indiana

|