Synthesis Report 94A Summary of the Research on the Effects of Test Accommodations, 2011-2012Christopher M. Rogers, Sheryl S. Lazarus, and Martha L. Thurlow September 2014 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Rogers, C. M., Lazarus, S. S., & Thurlow, M. L. (2014). A summary of the research on the effects of test accommodations, 2011-2012 (Synthesis Report 94). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Table of Contents

Executive SummaryThe use of accommodations in instruction and assessments continues to be of great importance for students with disabilities. This importance is reflected in an emphasis on research to investigate the effects of accommodations. Key issues under investigation include how accommodations affect test scores, how educators and students perceive accommodations, and how accommodations are selected and implemented. The purpose of this report is to provide an update on the state of the research on testing accommodations as well as to identify promising future areas of research. Previous reports by the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) have covered research published since 1999. We summarize the research to review current research trends and enhance understanding of the implications of accommodations use in the development of future policy directions, implementation of current and new accommodations, and valid and reliable interpretations when accommodations are used in testing situations. For 2011 and 2012, 49 published research studies on the topic of testing accommodations were found. Among the main points of the 2011-12 research are:

The studies in 2011-2012 demonstrated several similarities when viewing them in comparison with previous research, especially in relation to the 2009-2010 studies examined in our previous accommodations research review. Continuing trends showed more empirical research on accommodations effects at the postsecondary level, and increased accommodations perceptions research that involved educators. Researchers continued to build evidence about oral delivery, computer administration, calculators, and extended time, yet they also examined unique or unusual accommodations, including some high-tech accommodations. Accommodations for mathematics and reading testing continued to receive attention. Research designs with multiple purposes persisted. Still, there were several differences, or shifts, as well between research conducted in 2009-2010 and 2011-2012. Science assessment accommodations research decreased. Inquiry about construct validity became more complex, permitting the identification of factors that might influence the interface of accommodations with assessments of specific academic subjects. Top of Page | Table of Contents OverviewAll students, including students with disabilities, are required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004 and Title I of the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) to participate in assessments used for accountability. Some students need accommodations to meaningfully access assessments. States and assessment consortia look to accommodations research when making policy decisions about accommodations. To synthesize accommodations research efforts completed across the years, the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) has published a series of reports on accommodations research. The time periods included 1999-2001 (Thompson, Blount, & Thurlow, 2002), 2002-2004 (Johnstone, Altman, Thurlow, & Thompson, 2006), 2005-2006 (Zenisky & Sireci, 2007), 2007-2008 (Cormier, Altman, Shyyan, & Thurlow, 2010), and 2009-2010 (Rogers, Christian, & Thurlow, 2012). This report covers the time period 2011-2012. The purpose of this report is to present a synthesis of the research on test accommodations published in 2011 and 2012. The literature described here encompasses empirical studies of score comparability and validity studies as well as investigations into accommodations use, implementation practices, and perceptions of their effectiveness. As a whole, the current research body offers a broad view and a deep examination of issues pertaining to assessment accommodations. Reporting the findings of current research studies was a primary goal of this analysis; a secondary goal was to identify areas requiring continued investigation in the future. Review ProcessSimilar to the process used in past accommodations research syntheses (Cormier et al., 2010; Johnstone et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2012; Thompson et al., 2002; Zenisky & Sireci, 2007), a number of sources were accessed to complete the review of the accommodations research published in 2011 and 2012. Specifically, five research databases were consulted: Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, Digital Dissertations, and Educational Abstracts. To help confirm the thoroughness of our searches, we used the Web search engine Google Scholar to search for additional research. In addition, a hand-search of 47 journals was completed, in efforts to ensure that no qualifying study was missed. A list of hand-searched journals is available on the National Center on Educational Outcomes website (www.nceo.info/OnlinePubs/AccommBibliography/AccomStudMethods.htm). Online archives of several organizations were also searched for relevant publications. These organizations included Behavioral Research and Teaching (BRT) at the University of Oregon (http://brt.uoregon.edu), the College Board Research Library (http://research.collegeboard.org), the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST; http://www.cse.ucla.edu), and the Wisconsin Center for Educational Research (WCER; http://testacc.wceruw.org/). The initial search was completed in December, 2012. A second search was completed in April, 2013, and a third search in June, 2013, to ensure that all articles published in 2011 and 2012 were found and included in this review. Within each of these research databases and publications archives, we used a sequence of search terms. Terms searched for this review were:

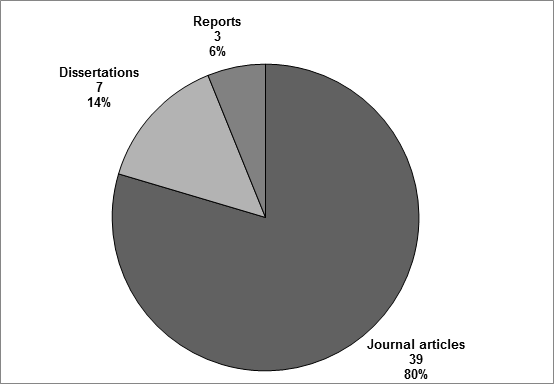

Many of these search terms were used as delimiters when searches yielded large pools of documents found to be irrelevant to the searches. The research documents from these searches were then considered for inclusion in this review with respect to several criteria. First, the decision was made to focus only on research published or defended (in doctoral dissertations) in 2011 and 2012. Second, the scope of the research was limited to investigations of accommodations for regular assessment; hence, articles specific to alternate assessments, accommodations for instruction or learning, and universal design in general were not part of this review. Third, research involving English language learners (ELLs) was included only if the target population was ELLs with disabilities. Fourth, presentations from professional conferences were not searched or included in this review, based on the researchers’ criteria to include only research that would be accessible to readers and that had gone through the level of peer review typically required for publication in professional journals or through a doctoral committee review. (This criterion was implemented for the first time during the 2007-2008 review.) Finally, to be included in the online bibliography and summarized in this report, studies needed to involve (a) experimental manipulation of an accommodation, (b) investigation of the comparability of test scores across accommodated and non-accommodated conditions, or (c) examination of survey results about students’ or teachers’ knowledge or perceptions of accommodations. To reflect the wide range of accommodations research that was conducted in 2011 and 2012, the studies are summarized and compared in the following ways: (a) purposes of research; (b) research type and data collection source; (c) assessment or data collection focus; (d) characteristics of the independent and dependent variables under study; (e) comparability of findings between studies in similar domains; and (f) limitations and directions of future research. The information provided in each of these categories should provide insight into the current state of accommodations research in education and highlight trends in current accommodations research. Top of Page | Table of Contents ResultsThe results of our analyses of the 49 studies published from January 2011 through December 2012 are presented in substantive detail. We identify the studies’ publication types, as well as the range of research purposes. We specify the types of research approaches and the primary and secondary sources of data collection. We also describe the data collection methods and instruments. We report the academic content areas covered in the research. We depict research participants in terms of their being students, educators, and parents, their ages or grade levels, the participant sample sizes and disability status, and their disability categories. We report the types of accommodations studied. We also explicate the research findings in terms of the impact of accommodations as well as perceptions about accommodations, incidence of accommodations use, and implementation. Additional sections offer perspectives on accommodations in postsecondary education, the effects of accommodations on construct validity, and the association of accommodations to academic discipline. Finally, limitations and future research directions in the assembled body of research literature are presented as reported by the researchers. Accommodations research takes a variety of approaches. It ranges from a large-scale approach that might examine aggregated accommodations data to an approach that involves testing an individual accommodation for a specific disability category. This range of approaches is reflected in research questions that focus on areas such as: the use or implementation of accommodations; the perception of accommodations by educational professionals, students, and parents; and the effects of accommodations on test scores. Publication TypeThe results of the review process showed a total of 49 studies were published from January 2011 through December 2012. As shown in Figure 1, of these 49 studies, 39 were journal articles, 7 were dissertations, and 3 were published professional reports released by research organizations (e.g., CRESST, Behavior Research and Training). Figure 1. Percentage of Accommodations Studies by Publication Type

The total number of studies published on accommodations in 2011-2012 (n=49) increased only slightly since the previous report examining accommodations research published in 2009-2010 (n=48). There was an increase in the number of journal articles (n=36 in 2009-2010; n=39 in 2011-2012), and a slight decrease in the number of dissertations published on accommodations (n=10 in 2009-2010; n=7 in 2011-2012). The report on accommodations research in 2009-2010 included 36 articles from 24 journals; the 39 articles described in the current report were found in 23 journals. In 2011-2012 there was a mean of 1.7 articles per journal that included any papers about accommodations, as compared to 2009-2010 when there was a mean of 1.5 articles per journal. Purposes of the ResearchA number of purposes were identified in the accommodations research published in 2011 and 2012. Table 1 provides a view of the predominant focus of each of these 49 studies. Ten studies listed single purposes (see Appendix A). The majority of studies sought to accomplish multiple purposes. In those cases, we identified the “primary purpose” according to the title of the work or the first-mentioned purpose in the text of the work. Table 1. Primary Purpose of Reviewed Research

The most common primary purpose for research published during 2011-2012 was to report on the effect of accommodations on test scores (41%) by comparing scores of students who received accommodations to those who did not (see Table A-1 in Appendix A). The next most common primary purposes were studying perceptions of the accommodations and preferences between or among a small number of accommodations of a certain type, reporting on implementation practices and accommodations use, and comparing test items. The third most frequent purpose, comparing test items, refers to whether item difficulty or other item-specific content validity issues changed when test format changed. Examples of these types of format changes included: from print-based to electronic (e.g., Alt & Moreno, 2012; Taherbhai, Seo, & Bowman, 2012), or from print to audio presentation (e.g., Shelton, 2012). The results presented in Table 1 include some literature reviews. We identified the primary purpose of summarizing research in studies that were expressly written as literature reviews; for example, Smith and Amato (2012) inquired about the impact of various accommodations on the assessment outcomes of students with visual impairments. Investigating test structure and identifying predictors of the need for accommodations were each fairly uncommon as a primary study purpose, each represented by less than 3% of the studies (n=1; test structure was primarily investigated in Posey & Henderson, 2012; identifying predictors was primarily identified in Brown, Reichel, & Quinlan, 2011). Table 2 provides a more detailed view of the accommodations research body of literature. It shows the multiple purposes of many studies. These multi-purpose studies contained up to four different purposes, but most commonly there were two purposes. For example, some efforts (Feldman, Kim, & Elliott, 2011; Kim, 2012; Patterson, Higgins, Bozman, & Katz, 2011; Schmitt, McCallum, Hennessey, Lovelace, & Hawkins, 2012; Schmitt, McCallum, Rubinic, & Hawkins, 2011) included analyses of score comparisons between students with disabilities and students without disabilities when using accommodations, yet also studied perceptions by analyzing students’ comments through survey or interview about their test-taking experience. Table 2. All Purposes of Reviewed Research

a The total of these percentages is >100% due to the multiple purposes identified in most (39) of the studies; 26 of the studies had 2 identified purposes, 9 of the studies had 3 identified purposes, and 5 of the studies had 4 identified purposes.When all purposes (i.e., primary, secondary) are included, the most common single purpose of the 2011-2012 published studies was inquiring from study participants about their perceptions of accommodations. The second most common purpose in this set of studies was demonstrating the effect of accommodations on test scores. Study approaches either compared test scores of students with disabilities and students without disabilities when using accommodations, or compared test scores of students with disabilities when using and not using accommodations. Each of these approaches was used in about half of this category of research. These first two purposes were both investigated in many of the 2011-2012 studies (n=11; see Tables A-1 and A-2 in Appendix A). Another purpose we identified in almost one-third of the studies was summarizing research on test accommodations, when a substantive part of the document was devoted to a comprehensive review of accommodations and their effects. All of the dissertations (n=7) among these studies, along with literature reviews, were identified with this purpose. Although not reported as a primary purpose, discussing issues was identified in almost one-third of the studies, usually noted when the researchers offered detailed considerations of central issues related to accommodations. For example, Holmes and Silvestri (2012) presented information about availability of assistive technology for postsecondary students with disabilities. The purpose of reporting on implementation practices and/or accommodations use was part of nearly one-fourth of the studies. For example, Qi and Mitchell (2012) detailed accommodations practice and use with the Stanford Achievement Test for deaf and hard-of-hearing children. The purpose of comparing test items co-occurred in some studies (n=4) on comparing scores between accommodated and non-accommodated tests adding a focus on analyzing differential item functioning (DIF). For instance, Flowers, Kim, Lewis, and Davis (2011) compared effects of oral delivery when provided on print tests and computerized tests, and also examined differential benefits of standard print format and computerized format on individual items. Additionally, comparison of test items was part of studies that simultaneously considered construct validity. For example, Cho, Lee, and Kingston (2012) measured whether item characteristics were related to item difficulty, and also analyzed whether item functioning was related to use of an accommodations package to discern test validity. The least common purposes, evaluating test structure and predicting the need for accommodations, were investigated by two studies each. An example of the former was when Posey and Henderson (2012) sought expert feedback in examining test features. An example of the latter was when Zebehazy, Zigmond, and Zimmerman (2012) analyzed the score patterns of students with visual impairments to discern the need for the accommodations that they received. Research Type and Data Collection SourceAbout two-fifths of the accommodations research reviewed here used a quasi-experimental research design to gather data for their research purposes. As seen in Table 3, in over twice as many quasi-experimental studies (n=14), researchers themselves gathered the data (i.e., primary source data), compared to studies with secondary data sources (n=6), such as extant or archival data. The number of quasi-experimental research studies increased slightly in 2012 compared to 2011, while the number of studies using a descriptive quantitative design remained the same. Researchers reported using truly experimental studies only 2 times in 2011 and 3 times in 2012. Though few studies were reported to use descriptive qualitative, longitudinal, or meta-analytic designs, these categories also were rarely included in past reports. Furthermore, there appeared to be a small difference between data collection sources, with almost two-thirds of studies using primary sources and over one-third of studies using secondary sources of data. This is similar to the previous report in which a similar proportion of about twice as many studies used primary data in comparison with secondary data sources. Table 3. Research Type and Data Collection Source by Year

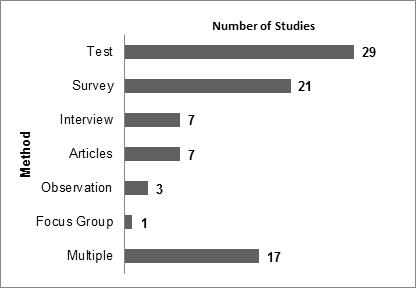

Data Collection Methods and InstrumentsThe researchers collected study data that were gathered through primary or secondary procedures using various methods and tools, as seen in Figure 2. Most of the research (n=29; 59%) included in this synthesis for 2011-2012 used data acquired through academic content testing. About two-fifths (n=21) of the studies employed surveys to gather data. Interviews were used much less frequently. For this analysis, we considered “articles” the method or source for those studies that reviewed research, including one study that employed formal meta-analysis. Three studies used observations, and one study used focus groups as a data source. Over one-third of the studies reported using more than one method or tool to gather data. Figure 2. Data Collection Methods Used in 2011-2012 Research

Note. Of the 49 studies reviewed for this report, 14 reported using two data collection methods, and 3 reported using three data collection methods.Nearly all of the 2011-2012 studies used data collection instruments of one form or another; only four studies did not employ any instruments. Table 4 presents the types of data collection instruments used in studies. Surveys presented items of an attitudinal or self-report nature. Tests were course- or classroom-based. Assessments were statewide or large-scale in scope. Protocols refer to nonacademic sets of questions, usually presented in an interview or focus group format. Measures referred to norm-referenced academic or cognitive instruments. All of these instruments were placed into five categories: protocols or surveys developed by study authors, norm-referenced cognitive ability measures, norm-referenced academic achievement measures, state criterion-referenced academic assessments, and surveys or academic tests developed by education professionals or drawn by researchers from other sources. Non-test protocols developed by the author or authors of the studies—the most commonly-used instrument type—included performance tasks, questionnaires or surveys, and interview and focus-group protocols, among others. Surveys or academic tests developed by education professionals or researchers used sources outside of current studies, and were exemplified by perception surveys such as the Accessibility Rating Matrix (ARM; Beddow, Elliott, & Kettler, 2009; as in Kettler, et al., 2012), or by subsets of items drawn from released or otherwise-available pools such as the Discovery Education Assessment (e.g., Beddow, 2011). State criterion-referenced assessments included those of Georgia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, as well as some from states that remained unidentified in the research. Nine norm-referenced academic achievement measures were used in one or more studies, including the TerraNova Achievement Test and the Nelson-Denny Reading Test (NDRT). Norm-referenced cognitive ability measures included the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—Fourth Edition (CELF-4), among others. A substantial minority—16 studies in all—used instrumentation of more than one kind. Additionally, a small number of studies used multiple instruments in each of them, often of the same kind (Brown et al., 2011; Feldman et al., 2011; Shelton, 2012; Srivastava & Gray, 2012). A small number (n=3) of instruments was used in more than one study: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—Fourth Edition (CELF-4), the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), and Georgia’s Criterion-Referenced Competency Tests (CRCT) in mathematics. We present a complete listing of the instruments used in each of the studies in Appendix C, including the related studies that served as sources for these instruments, when available. Table 4. Data Collection Instrument Types

1 Other: 1 study used an observation procedure (Bouck, Flanagan, & Joshi, 2011), 1 study used a college course exam (Makeham & Lee, 2012).2 4 studies were literature reviews employing various data collection approaches and/or instruments (Holmes & Silvestri, 2012; Lovett, 2011; Shinn & Ofiesh, 2012; Smith & Amato, 2012).Content Area AssessedA number of studies published during 2011-2012 focused on accommodations used in certain academic content areas. As shown in Table 5, math and reading were the two most commonly studied content areas. Table 5 also provides a comparison to content areas in NCEO’s previous reports on accommodations (Rogers et al., 2012; Cormier et al., 2010). In general, the emphasis on reading and math is consistent across reviews. The number of studies on writing, social studies, and psychology has remained fairly consistent since 2005. An increase in science studies, apparent in previous years, was not evident in the current report, where there was a decrease in numbers. There have been no studies citing Civics/U.S. History since 2005-2006, so we did not include this content area in the current report. Two studies published in 2011-2012 did not specify a content area. This is a change from the last report, in which all studies specified the content areas of the assessments and their accommodations. Table 5. Academic Content Area Assessed Across Three Reports

a Studies in 2007-2008 including examinations of more than one content area ranged in number of areas assessed from 2 to 4.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Number of Research Participants by Study |

Number of Studies by Proportion of Sample Comprising Individuals with Disabilities |

|||||

|

0-24% |

25-49% |

50-74% |

75-100% |

Unavail.1 |

Total |

1-9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

5 |

10-24 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

25-49 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

50-99 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

100-299 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

300-499 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

500-999 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1000 or more |

4 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

9 |

Unavailable2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Total |

9 |

6 |

4 |

15 |

1 |

34 |

a 1 study did not specify the proportion of participants who had disabilities.

b 1 study did not specify the number of participants.

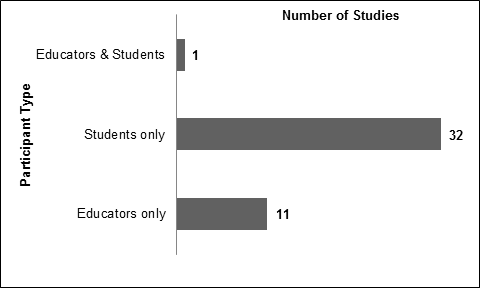

In 2011-2012, there was a larger number of studies in which at least 50% of the participants were people with disabilities (n=18) than there were studies with fewer than 50% of the participants being people with disabilities (n=15); only one study did not have the number of participants available (Taherbhai et al., 2012). The six studies with between 25% and 49% people with disabilities had participant group sizes ranging from 39 to 1,944, and involved only student participants. Of the nine studies with fewer than 25% people with disabilities, six studies ranged in participant numbers from 282 to 769,550, and these six studies were focused on student assessment performance; further, four of these studies examined extant data sets of over 50,000 students each. The other three studies in that set were focused on educators’ perceptions and knowledge of accommodations (Brockelmann, 2011; Phillips et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2011). There were only three studies with 50% people with disabilities and 50% without disabilities, and they each had fewer than 50 participants, who were students.

Fifteen studies examined participant groups composed almost entirely of people with disabilities; these are reported in the 75-100% column. In fact, 14 of these 15 studies focused only on students with disabilities. The exception was a study (Kuti, 2011) that engaged 8 educators in providing qualitative interview data and examined extant data from 7,002 students with disabilities. Of the studies involving more than 50% participants with disabilities, there were three distinct group sizes: fewer than 25, between 50 and 299, and over 4,000. Finally, almost all of the 2011-2012 studies reported sufficient data to determine the proportion of study participants who had disabilities and who did not have disabilities. This observation substantially contrasts with information from the 2009-2010 studies, when about 25% of the studies did not have sufficient data to determine these proportions. However, unlike the previous reporting period which had a complete accounting of the number of participants in the relevant studies, there was a study that did not publish the exact proportion of participants with disabilities, due to circumstances explained in that study (Patterson et al., 2011).

School Level

Research on accommodations published during 2011 and 2012 involved kindergarten through college-aged participants (see Table 7). Previous reports included research with participants in kindergarten through postsecondary (see Appendix D for more detail). Postsecondary included both university participants and participants in other postsecondary settings. For example, Ihori (2012) investigated the perspectives of faculty members in two-year and four-year higher education institutions, and Gregg and Nelson (2012) gathered accommodated test scores from students transitioning from postsecondary settings to work settings. This shift toward including studies about accommodations in testing for postsecondary-aged youth began in the previous report (Rogers et al., 2012).

As seen in Table 7, a plurality of the studies published in 2011 and 2012 focused on middle school students (n=21). Twelve studies involved elementary school students, and ten involved high school students. Nearly one-quarter of the studies (n=12) involved samples from across more than one grade-level cluster; nearly all of these studies included relatively larger groups of 50 or more participants (91%), and one-half of them used secondary data sources (see Appendices B and D). Put another way, these multiple grade-level studies were either analyses of extant large-scale assessment data sets, often drawn at the state level, or examinations of data gathered by researchers under experimental and quasi-experimental conditions. Although not more common than K-12 studies, there was a noteworthy number of studies that examined accommodations use and implementation at the postsecondary/college level; further, some (n=2) of these involved adult learners who were not in formal higher education institutions. For example, Patterson and her colleagues (2011) piloted the General Equivalency Diploma (GED) mathematics test in a computerized form with accessibility tools to provide for adult learners’ accommodations needs.

Table 7. School Level of Research Participants

Education Level of Participants in Studies |

Number of Studies |

Elementary school (K-5) |

12 |

Middle school (6-8) |

21 |

High school (9-12) |

10 |

Postsecondary |

6 |

Multiple grade-level clusters |

12 |

Not applicable (No age) |

12 |

Disability Categories

A broad range of disability categories was included in samples in the 2011-2012 research (see Appendix D for details). As shown in Table 8, seven studies did not specify disability categories of student participants, eleven studies did not include students in the sample, and five studies did not enumerate participants. Of the remaining 26 studies, the most commonly studied disability category was learning disabilities (n=17); five of these studies had only participants with learning disabilities, and four more compared students with learning disabilities to students without disabilities. About one-fourth of these remaining 26 studies included students with blindness/visual impairments (n=7), students with emotional behavioral disabilities (n=6), or students with speech/language impairments (n=6). About one-fifth of the 26 studies included students with deafness/hearing impairments (n=5), and another one-fifth included students with autism (n=5). The lowest proportions of studies—between one-sixth and one-eighth—included students with attention problems, students with physical disabilities, or students with intellectual disabilities. Only two studies reported participants with “multiple disabilities.” Over one-half of relevant studies included students without disabilities as comparison groups.

Besides students with learning disabilities, very few studies examined accommodations for only participants with one specific category of disabilities: students with blindness/visual impairments, 2 studies (Kim, 2012; Posey & Henderson, 2012); students with hearing impairments, 1 study (Cawthon, Winton, Garberoglio, & Gobble, 2011); students with speech/language impairments, 1 study (Koutsoftas & Gray, 2012); students with autism, 1 study (Alt & Moreno, 2012); and students with attention problems, 1 study (Brown et al., 2011). Eight studies included participant groups with various disabilities, rather than all having one specific category of disability.

Table 8. Disabilities Reported for Research Participants

Disabilities of Research Participants |

Number of Studies |

Learning disabilities |

17 |

Blindness/Visual impairment |

7 |

Emotional behavioral disability |

6 |

Speech/Language |

6 |

Deafness/Hearing impairment |

5 |

Autism |

5 |

Attention problem |

4 |

Physical disabilitya |

3 |

Intellectual disabilities |

3 |

Multiple disabilitiesb |

2 |

No disability |

15 |

Not specifiedc |

8 |

Not applicabled |

11 |

a Physical disability = mobility impairments and/or impairment with arm use.

b Multiple disabilities = individual students who were each specifically categorized as having more than one disability.

c Not specified = those studies or reviews (1) of studies that did not report about or provide detail as to the participants’ disabilities.

d Not applicable = those documents that had only non-students as participants.

Types of Accommodations

The number of times specific categories of accommodations were included in 2011-2012 published research is summarized in Table 9. Presentation accommodations were the most frequently studied category (n=35), and within this category the most common accommodation was oral delivery—including human reader, and via technology (n=23). The next three most common presentation accommodations were computer administration (n=9), large print (n=8), and braille (n=7). The next most frequent category studied was response accommodations (n=23), and in that category, dictated response (n=11) was the most common accommodation. It should be noted that the computer administration accommodation fits into three categories: presentation, equipment/materials, and response. The next most common response accommodation was dictated response (n=8).

Several studies (n=28) analyzed accommodations from more than one category. For example, Kim (2012) studied students with visual impairments who were provided the read-aloud accommodation by a human reader, in addition to other accommodations including large print, braille, and extended-time. Two studies—Beddow (2011) and Fox (2012)—examined accommodations as they were naturalistically identified in students’ IEPs, and their effects were not individually measured. Many of these instances of multi-category accommodations studies are related to the fact that some accommodations fit into more than one category. For example, studies examining computer administration (n=10) fit into three categories: presentation, equipment/materials, and response. In contrast, fewer studies (n=13) investigated accommodations within the same category. In fact, nearly all of these studies (n=11) focused on single accommodations, and most of them studied either read-aloud (n=6) or extended-time (n=4). A complete listing of accommodations examined in each study is provided in Appendix E.

Table 9. Accommodations in Reviewed Research

Accommodation Category |

Number of Studies |

Presentation |

35 |

Equipment/Materials |

20 |

Response |

23 |

Timing/Scheduling |

17 |

Setting |

8 |

Multiple accommodations |

29 |

Research Findings

The findings of the studies about accommodations published in 2011 and 2012 are summarized in Tables 10-20. We present information according to the nature of the studies, in keeping with the range of their purposes and focuses. The findings included sets of research about specific accommodations: oral delivery, computer administration, extended-time, calculator, and aggregated sets of accommodations commonly called “bundles.” We also report the findings about unique accommodations—those examined in only one study each—including a specialized calculator, American sign language (ASL) via digital video, word-processing, and visual chunking representation. We also report about descriptions of perceptions about accommodations, including those of student test-takers as well as educators. We summarize the findings of the accommodations, and describe a range of implementation conditions as well as incidence of use of various accommodations across large data sets. The findings from studies in postsecondary educational contexts, which have grown over time from 6 or 7 in our past three reports to 11 in this report, are given separate attention. This report also presents findings by academic content areas: math, reading, science, and writing. In Appendix F, we provide substantial detail about individual studies.

Impact of Accommodations

Research examining the effects of accommodations on assessment performance for students with disabilities comprised 29 studies published in 2011 and 2012 (see Table 10; see also Appendix F, Tables F-1 to F-6 for details about each study of this type). We detail the effects of these four discrete accommodations—oral delivery, computer administration, extended time, and calculator—along with lists of aggregated accommodations and uncommon accommodations.

Oral delivery, provided using text-to-speech devices or human reader, was the single most investigated accommodation in 2011-2012 with six studies. For clarity in this report, we used “oral delivery” in place of “read aloud” to explicitly acknowledge the range of media formats used, including human readers, recordings of assessment items or instructions, and text-reading software or text-to-speech devices. The delivery methods that do not use human delivery of the accommodation have been increasing in research attention.

Of the six studies examining oral delivery, three studies supported performance improvements for some students with disabilities but not all or in some testing conditions but not all. Lazarus, Thurlow, Rieke, Halpin, and Dillon (2012) noted no average score differences for the 24 participants as a whole when using and not using a human reader, yet found that individual scoring patterns indicated that seven participants scored higher when using read-aloud, eight scored higher when not using read-aloud, and nine scored the same under both conditions. Schmitt and colleagues (2012) found that the three college student participants with reading disabilities varied in degree of score improvement on reading comprehension, when using a ReadingPen Advanced Edition (2006) device with a digitized voice. Comparing each student’s scores under a control condition, when using the device for only decoding, and for decoding and seeking vocabulary definitions, researchers indicated that the student with lowest comprehension skills benefited most in both reading pen conditions in contrast to the other students, who scored better when not using the accommodation. The same least-skilled individual student benefited more from the reading pen’s decoding support than from using it for both decoding and vocabulary definition. In a similar study, which measured comprehension accuracy and comprehension rate per minute, Schmitt and colleagues (2011) found that high school students with learning disabilities using a ReadingPen Advanced Edition (2006) device to decode words and to define vocabulary words scored worse on rate than when using it to decode words only. Two of the three participants scored highest on accuracy without the accommodation. The other three oral delivery findings seemed at odds with one another. Shelton (2012) found that audio-recorded oral delivery supported score improvements for both students with and without (learning) disabilities. Kim (2012) found that students with disabilities (visual impairments) scored differentially better with support of an human reader. Holmes and Silvestri (2012) summated that the studies on assistive technology (AT) indicated that text-to-speech supported reading, and also provided additional benefits, such as improvement in comprehension, task persistence, and reading rate. (See Appendix F, Table F-1.)

Computer administration, which is both a presentation and response accommodation, was the next most frequently-studied accommodation in the 2011-2012 published literature, comprising one-seventh of the effect studies (n=4). Most of the study findings (75%) indicated that use of computer administration as a stand-alone accommodation (i.e., it was not bundled with other accommodations), did not result in higher performance for students with disabilities. This result occurred for youth and adults completing the General Equivalency Diploma exam (Patterson, Higgins, Bozeman, & Katz, 2011), grade 8 students with and without language-learning disabilities completing reading comprehension assessments (Srivastava & Gray, 2012), and students in grades 7 and 8 with learning disabilities matched with similar-ability students without disabilities completing reading and math state assessments (Taherbhai, Seo, & Bowman, 2012). The study (Alt & Moreno, 2012) that differed in findings from these three studies compared test formats for age 5-13 year old students with and without autism spectrum disorders on expressive and receptive language and found that students with disabilities did not differentially benefit from computerized test format when comparing their scores with those of students without disabilities, who were matched for age and sex. (See Appendix F, Table F-2.)

The extended-time accommodation was investigated in three studies (Brown, Reichel, & Quinlan, 2011; Gregg & Nelson, 2012; Lovett, 2011). The findings about the effect of extended time on assessment scores varied widely, yielding no consensus. One study (Brown et al., 2011) indicated that extended time supported improved reading comprehension scores for students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A meta-analysis (Gregg & Nelson, 2012) indicated that studies published from 1986 through 2006 supported the differential boost hypothesis, that is, students with disabilities scored significantly better with extended time than without, and had differentially greater score gains than did students without disabilities using extended time (in comparison with their standard performance). In contrast, one study (Lovett, 2011) reported that students without disabilities improved scores in a similar manner to students with disabilities. (See Appendix F, Table F-3.)

Effects of the calculator accommodation were explored in three studies. Two studies yielded the conclusion that all students, both with and without disabilities, improved in performance on a math state assessment when using calculator as an accommodation (Engelhard, Fincher, & Domaleski, 2011) or as a modification (Randall, Cheong, & Engelhard, 2011). In addition, item-level analyses of extant state math assessment data demonstrated that the benefit of the calculator use for students with disabilities was complicated by the relative difficulty of the items. On items that had low difficulty, due to requiring lower-level skills such as operation and number sense, students with disabilities benefited when using calculators on these easier items. In contrast, students with disabilities not using calculators performed better on items requiring higher-level skills. (See Appendix F, Table F-4.)

Two studies examined effects of resource guides on assessment performance. In one study, Engelhard and colleagues (2011) conceptualized the resource guide as expressly not providing information that would affect the construct being tested, but instead provided scaffolding supports that could assist students with disabilities with eliminating construct-irrelevant barriers to assessment. The study results indicated that the resource guide did not support an improvement in math assessment performance, either for students with disabilities, or students without disabilities (Engelhard et al., 2011). In the other study, Randall and colleagues (2011) used the term “modification” when referring to the resource guide. The study results yielded that both students with disabilities and students without disabilities performed better when using the resource guide modification than when not using it, with no differential benefit for either group of students (Randall et al., 2011).

Researchers in five studies scrutinized effects of different aggregated sets of accommodations—also called accommodations packages or bundles. These studies used five different aggregations of accommodations, and the effects of their uses during assessment were also divergent. One study (Feldman, Kim, & Elliott, 2011) indicated that use of various accommodations packages individualized to students with disabilities during a reading/language arts achievement test supported score improvements for both students with and without disabilities in an equal manner. Another study’s results yielded that different accommodations packages supported improved scores for students with disabilities (Flowers, Kim, Lewis, & Davis, 2011; Kim, 2012). Flowers and her colleagues (2011) studied effects on test performance of students with disabilities in grades 3-11, when using an oral delivery accommodation via text-to-speech software, in combination with a computerized or print format, on state assessments in reading, science, and mathematics. Examining effect sizes, the researchers found no differing results between or across grade levels, but did note that there were larger effect sizes for reading than for math. In addition, there were small to moderate effect size differences that tended to favor the printed text with human reader accommodations package.

In a study examining sets of accommodations and modifications, termed enhancement packages, Kettler and his colleagues (2012) concluded that the collection of assessment enhancements supported improvements in science assessment performance for both students with disabilities and students without disabilities. Additional analyses indicated that only 7 of the 40 items demonstrated a differential boost, and 11 showed a minimal differential boost. The researchers indicated that some enhancements did not seem to benefit test-takers while others did, making the results unclear overall (Kettler et al., 2012). Finally, Kim (2012) found that when human readers provided the accommodation along with large print, braille, and extended time, students with visual impairments scored better in reading comprehension (in Korean language, in South Korea) than when using these other accommodations without read aloud. (See Table 10 for detail about findings of each study; also, see Appendix F, Table F-5.)

We classified five studies as having investigated the impact of unique accommodations (i.e., accommodations that were the focus of just one study during the two years included in this report). Two studies reported that the unique accommodations did not support improved performance for students with disabilities: the voice input, speech output (VISO) calculator (Bouck, Flanagan, & Joshi, 2011) and American sign language (ASL) presented by an interpreter on digital video (Cawthon, Winton, Garberoglio, & Gobble, 2011). The former study investigated the VISO calculator’s impact on mathematics test behavior, and the latter study inquired about ASL via DVD for test directions and ASL via DVD for test items, and the possibility of different effects on reading and math achievement measures. Two unique accommodations—word processing (Holmes & Silvestri, 2012) and visual chunking representation (VCR; Zhang, Ding, Stegall, & Mo, 2012)—supported improved performance for students with disabilities. The effects of word processing on written products at the postsecondary level, and the literature review, indicated that the outcomes were improved spelling error detection, higher grade point averages, and increased course-completion rates for students with learning disabilities to a level equivalent to that of students without disabilities (Holmes & Silvestri, 2012). Visual chunking’s purpose was to support the visual memory of grade 3 students with math-related disabilities, and geometry assessment scores improved significantly when using VCR (Zhang et al., 2012). Finally, one study (Kettler et al., 2012) provided evidence about three unique enhancements (i.e., shorter item stems, bulleted text, simplified graphics). When examined separately, shorter item stems supported improved performance for all students, and bulleted text and simplified graphics did not support improvements for either students with disabilities or students without disabilities. (See Table 10 for detail about findings of each study; also, see Appendix F, Table F-6.)

Table 10. Summary of Research Findings by Specific Accommodation (n=23)

Accommodation Studied (total) |

Finding |

Number of Studies |

FREQUENTLY-STUDIED |

16 |

|

Oral delivery (5) |

The oral delivery accommodations supported improvement in assessment performance for some but not all students with disabilities or in some but not all testing conditions |

3 |

The oral delivery accommodation supported improved assessment performance and in other ways beyond for students with learning disabilities |

1 |

|

The oral delivery accommodation supported improved assessment performance of all students |

1 |

|

Computer administration (3) |

The computer administration accommodation did not support improved scores for students with disabilities more than the paper assessment format |

2 |

The computer administration accommodation did not support improved assessment performance for all students |

1 |

|

Extended-time (3) |

The extended-time accommodation supported improved scores for students with disabilities |

1 |

The extended-time accommodation supported score improvements differentially for students with disabilities compared to those of students without disabilities |

1 |

|

The extended-time accommodation supported improved scores for all students |

1 |

|

Calculator (2) |

The calculator accommodation supported improved performance for all students |

1 |

The calculator accommodation had mixed results for students with disabilities |

1 |

|

Aggregated set (3) |

Accommodations package supported improved scores for all students in an equal manner (Package: any combination of the following: unlimited time, highlighting test directions, read-aloud directions only, test books in large-print format, student dictation to a human scribe, and allowing frequent rest breaks) |

1 |

An accommodations package supported improved scores for students with disabilities more than another accommodations package (Packages: computerized vs. print format, with oral delivery accommodation via text-to-speech software AND oral delivery accommodation via human reading aloud in combination with large print, braille, and extended time) |

1 |

|

Accommodations package supported improved scores for students with disabilities (Package: oral delivery accommodation via human reader in combination with large print, braille, and extended time) |

1 |

|

UNCOMMON / UNIQUE |

7 |

|

Voice-input, speech output (VISO) calculator |

The unique accommodations did not support improved performance for students with disabilities |

2 |

ASL via DVD for directions and items |

||

Word-processing |

The unique accommodations supported improved performance for students with disabilities |

2 |

Visual chunking representation to support working memory for visual images |

||

Math resource guides |

The unique enhancement did not support improved performance for all -- students with disabilities as well as students without disabilities |

1 |

Shorter item stems |

The unique enhancement supported improvements differentially for a subset of students with disabilities |

1 |

Bulleted text and simplified graphics |

The unique enhancement did not support improvements differentially for a subset of students with disabilities |

1 |

Perceptions about Accommodations

Table 11 shows the set of 25 findings from 24 studies on perceptions about accommodations or modifications. Over one-half of the perceptions studies (n=13) reported on student perceptions only, while a slightly smaller proportion (46%) reported on educator perceptions only; one study (Flowers et al., 2011) examined the perceptions of both educators and students. Studies on student perceptions found that students viewed accommodations or modifications as helping them perform better on assessments (Beddow, 2011; Kettler et al., 2012; Lazarus et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012), and supported them while taking assessments by benefiting them in some other way (Bouck et al., 2011; Feldman et al., 2011; Patterson et al., 2011; Shelton, 2012). Three studies (Makeham & Lee, 2012; Schmitt et al., 2012; Schmitt et al., 2011) found that there were conflicting views among student participants about unique accommodations, such as the iPod aural presentation and the “reading pen.” Some students indicated that using an iPod to access test items was beneficial and supported understanding through intonation and pacing; others indicated that this unique oral-delivery medium provided little or no benefit (Makeham & Lee, 2012). For the reading pen, some indicated that they enjoyed using this tool, and slightly fewer indicated the opposite. Each study had only three participants. Schmitt and colleagues (2012) found a pattern in student perception: the least-skilled test-taker expressed the least satisfaction from using the reading pen. Finally, two studies (Bolt et al., 2011; Kim, 2012) observed that students preferred some accommodations over others. For example, students with visual impairments preferred to use oral delivery accommodations along with braille or magnification rather than using only braille or magnification; alternately, students without disabilities predominantly preferred not to use oral delivery because their reading speed was quicker than the human reader’s speed (Kim, 2012).

The studies on educators’ perceptions of accommodations or modifications predominantly found that these enhancements to assessments were beneficial to student test-takers’ performance (Ihori, 2012; Leyser, Greenberger, Sharoni, & Vogel, 2011; Lipscomb, 2012) and to students’ motivation and endurance (Hodgson et al., 2012). Only one study (Meadows, 2012) indicated that some educators had less than favorable attitudes about accommodations. Meadows found that educators with less than a Master’s degree credentials and little teaching experience had less positive and supportive attitudes toward using assessment accommodations than other educators. Four studies reported about educators’ knowledge of and familiarity with accommodations. Three of these studies (Phillips et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2011) indicated a wide continuum of knowledge and familiarity among study participants in each study, including little or no certainty about their capabilities and relatively high degrees of confidence in their capabilities. In contrast, one study (Davis, 2011) yielded a narrower range of perceived knowledge of accommodations, in that participants reported only moderate to high levels of knowledge, with no participants having little or no accommodations knowledge. The researchers identified various factors mitigating knowledge and familiarity: depending on the accommodations categories (Davis, 2011) or the specific accommodations (Zhou et al., 2011), on the application of accommodations —such as instruction or assessment (Zhou et al., 2012), and on the number of instances of providing accommodations to students in an online class format (Phillips et al., 2012). The finding of perceptions from both the students’ and educators’ perspectives asserted that students preferred the accommodations package of computerized format with text-to-speech software over the package of printed text format with human reader; nevertheless, the assessment results did not support better performance using that package (Flowers et al., 2011). (See Appendix F, Table F-7 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

Table 11. Summary of Research Findings on Perceptions about Accommodations (n=24)

Study Findings |

Number of Studies |

Students |

13 |

Students indicated that using accommodations or modifications benefited them in terms of performance score |

4 |

Students indicated that using accommodations benefited them beyond performance score improvements |

4 |

Student perceptions were mixed about the accommodations studied |

3 |

Students expressed a preference for one accommodation over one or more others |

2 |

Educators |

11 |

Educators had similarly positive or supportive attitudes about accommodations or modifications |

3 |

Educators had varying degrees of positive or supportive attitudes about accommodations or modifications |

3 |

Educators indicated that they had various levels of familiarity or knowledge about accommodations |

3 |

Educators indicated that using accommodations benefited students beyond performance score improvements |

1 |

Educators indicated that they had moderate to high levels of knowledge about accommodations |

1 |

Educators and Students |

1 |

Participant groups had similar perspectives about accommodations provided |

1 |

Implementation and Use of Accommodations

Table 12 displays a summary of the 13 studies that reported 13 findings on incidence of accommodations use and implementation-related matters. The nature and outcomes of this set of studies were divergent overall, yet we identified some commonalities. In a few studies (Davis, 2011; Ihori, 2012, Phillips et al., 2012), researchers noted that implementation challenges and atypical use patterns affected accommodations practices. For instance, about 20% of postsecondary faculty participants expressed disagreement with the practice of providing specific response accommodations for students with ADHD (Ihori, 2012), and implementation barriers and facilitators were associated with training as well as educators’ demographics and grade levels of instruction (Davis, 2011). Researchers of three studies (Fox, 2012; Kim, 2011; Smith & Amato, 2012) reported that students with visual impairments were typically provided large print and extended-time accommodations, among others, on reading assessments. Fox (2012) added that other popular accommodations for this group of students with disabilities were small group and individual or separate room settings, and Smith and Amato (2012) clarified that most states also offered lighting adjustment as an accommodation.

In contrast with the previous report which noted that five studies observed that the most common accommodation for students with disabilities was small group administration, the current set of studies had a consensus of only two studies indicating that the most common accommodation for students with disabilities was extended time (Bolt, Decker, Lloyd, & Morlock, 2011; Lovett, 2011). Two studies (Hodgson et al., 2012; Holmes & Silvestri, 2012) elaborated implementation variations that oral-delivery accommodations have had, including co-occurring accommodations offered in combination with oral delivery, the considerations of providing the accommodation during math assessments (Hodgson et al., 2012), and the functions that text-to-speech software can offer during reading and writing assessments (Holmes & Silvestri, 2012). Individual findings were also provided in three other studies (Shinn & Ofiesh, 2012; Cawthon, 2011), including that students with hearing impairments are most often provided sign language and extended-time (Cawthon, 2011). (See Appendix F, Table F-8 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

Table 12. Summary of Research Findings on the Implementation of Accommodations (n=13)

Study Findings |

Number of Studies |

Implementation challenges and atypical use patterns affected accommodations practices |

3 |

Common accommodations for students with visual impairments on reading included large print and braille and extended-time |

3 |

The most common accommodation provided to students with disabilities was extended-time |

2 |

The oral delivery accommodation has had variations in its implementation |

2 |

Various factors complicated the provision of accommodations to students at the postsecondary level |

1 |

Common accommodations for students with hearing impairments included sign language interpretation and extra time |

1 |

Accommodations use patterns differed among students with visual impairments |

1 |

In Table 13, we report on the seven studies providing seven findings about academic construct validity when accommodations were used on state assessments. Two studies resulted in there being no effect of the accommodation on academic construct for reading (Posey & Henderson, 2012) and for reading, science, and mathematics (Flowers et al., 2011). Posey and Henderson (2012) reported that students with visual impairments using contracted braille performed similarly to students without disabilities not using accommodations. Also, when comparing a newer computerized test using text-to-speech software to the print format using a human reader, Flowers and colleagues (2011) determined through differential item functioning (DIF) analyses that, despite various differences on some items, there were no patterns showing that either format condition was favored more frequently than the other. Another study (Lovett, 2011) yielded an opposite result: extended time was shown in this review of the literature to have changed the meaning of students’ assessment performance. Further, item-level analyses using two different analysis approaches were conducted in another study (Randall, Cheong, & Engelhard, 2011). Randall and colleagues found that two problem-solving items included in a group of 10 items functioned differently under certain conditions. One problem-solving item was differentially more difficult for students with disabilities than for students without disabilities when presented without modifications, yet it was easier for students with disabilities when using the calculator modification. The other problem-solving item was found to be differentially easier for students without disabilities than for students with disabilities both with the calculator modification and with no modifications; the statistical significance of this finding differed between analysis approaches.

Two studies (Cho et al., 2012; Scarpati, Wells, Lewis, & Jirka, 2011) addressed the nuances of validity research, noting that various factors can complicate research results. Cho and colleagues (2012) reported that an accommodations package of read aloud, frequent breaks, and separate quiet setting improved scores for students with disabilities on some specific items, yet that students’ ability levels affected the degree of benefit from the accommodations package. Scarpati and colleagues indicated that both the difficulty level of individual items and the ability level ranges of students with disabilities can complicate research results. As Scarpati and colleagues noted, “students using calculators fared better on easier items whereas the nonaccommodated group fared better on more difficult items” (p. 60). Put another way, students using calculators did not derive any benefit from the accommodation when answering more difficult items unless the students also had higher math abilities. (See Appendix F, Table F-9 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

Table 13. Summary of Research Findings Pertaining to Accommodations and Modifications Validity (n=7)

Study Findings |

Number of Studies |

The accommodations did not change the construct |

2 |

The accommodations/modifications changed the construct |

2 |

Construct validity was affected by other factors |

2 |

The manner of scoring changed the construct/s being tested |

1 |

Accommodations in Postsecondary Education

In Table 14, we present a set of 15 findings from 11 studies that examined accommodations provided in educational settings beyond the K-12 school setting. Researchers investigated effects of accommodations on test performance, test-takers’ experiences using accommodations, and faculty members’ perceptions of accommodations, along with implementation practices and uses of accommodations; three studies each reported findings in two of these areas. The five studies (Gregg & Nelson, 2012; Gregg, 2012; Holmes & Silvestri, 2012; Posey & Henderson, 2012; Schmitt et al., 2012) examining accommodation effects included three literature reviews investigating multiple accommodations, as well as a study on contracted braille (Posey & Henderson, 2012) and a study on the reading pen (Schmitt et al., 2012). Gregg (2012) included a review of 32 studies about accommodations on testing for adult basic education learners. Over half (57%) of the studies examined effects of accommodations on university admissions testing. Nearly all (n=29) analyzed impacts of the extended-time accommodation, indicating that people with learning disabilities gained benefits.

The meta-analysis (Gregg & Nelson, 2012) focused on the effects of extended time for people in transition from secondary education, namely postsecondary students and youth with disabilities in work settings. The findings were mixed in the nine studies analyzed, five of which specifically examined effects on university admissions testing. Study participants scored significantly higher in all three studies comparing the extended-time condition to the non-accommodated condition, with medium to large effect sizes. In the two studies comparing performance of youth without disabilities when accommodated and not accommodated, they performed moderately better with accommodations, with small to large effect sizes. According to two studies, the extended-time accommodation provided a differential boost for scores of students with disabilities compared to those of students without disabilities. Additional explanations of the moderator variables, including academic content and type of test, were also reported in detail for those two sets of studies of a sufficient number.

Holmes and Silvestri (2012), in reporting about effects of assistive technology to support postsecondary students with learning disabilities, noted that there have been few studies on academic outcomes; they identified two studies that found that word-processing helped postsecondary students to improve spelling error detection, to increase GPAs, and to complete courses at a rate similar to the rate of students without disabilities. Posey and Henderson (2012) reported that contracted braille work-based reading skills scores for students with visual impairments were equivalent to the scores without the accommodation for students without disabilities. Schmitt and colleagues (2012) reported that the student with the lowest comprehension level demonstrated the most benefit from the reading pen (with digitized voice) from among the three students with reading disabilities, while the other two students’ reading comprehension scores decreased with the use of both forms of the accommodation from their scores without it. Further, the lowest-performing student performed better when using the decoding-only function in comparison to using the decoding and vocabulary definition functions.

The four studies reporting postsecondary faculty perceptions of accommodations (Brockelmann, 2011; Ihori, 2012; Phillips et al., 2012; and Posey & Henderson, 2012) yielded a variety of perspectives and ideas, partly related to their identities and roles, and other setting dynamics. All faculty participants in one study (Brockelmann, 2011) used similar numbers of accommodations during course examinations, but faculty in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) programs employed extended-time, individual setting, and exam formats—including read-aloud, dictated, typed, or scribed—more frequently than non-STEM faculty members, and STEM faculty regarded extended time as more effective than non-STEM faculty. Another study (Ihori, 2012) found no significant differences across faculty members in attitudes and beliefs about students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), knowledge of legal protections for this group, and willingness to accommodate them, based on institutional setting (i.e., two- or four-year institution, public four-year or private four-year institution).

Phillips and her colleagues (2012) surveyed a subset of faculty at one state public institution, those who teach online courses, and found that only one-third of participants (34%) felt capable of providing accommodations to students with disabilities, and that less than one-fourth (24%) had actually done so before, including extended time, alternate test formats, and assistive technology. The researchers also provided a list of disability categories and accommodations that faculty reported having provided. Posey and Henderson (2012) reported educators’ suggestions for improving testing administration to support adults in basic education to access testing.

Postsecondary students offered their perceptions about accommodations in testing in three studies (Bolt et al., 2011; Makeham & Lee, 2012; Schmitt et al., 2012). The findings of each study were unique, and we found little pattern to them as a group. Bolt and colleagues (2011) reported that the postsecondary students indicated that dictated response to a scribe and word processor with spell check were most helpful to them in the university setting, which were different from the most helpful accommodations during high school, which were extended-time and dictionary, along with dictated response to a scribe. The students varied in their experience of barriers to accommodations use, with about one-third (36%) identifying system-level issues, such as accessing support and selecting appropriate accommodations; on the other hand, about one-third (34%) of students indicated that facilitators of accommodations use were other individuals, and another one-third (32%) credited system-level issues.

Makeham and Lee (2012) indicated that most participants endorsed a strong preference for using oral-delivery accommodations via iPod in comparison with a human reader, and all participants expressed social discomfort, including embarrassment, when offered exam readers. In contrast, half of the participants reported that the iPod accommodation did not benefit them personally, and that any form of oral delivery would be similarly not helpful. Schmitt and colleagues (2012) reported that although the lowest-skilled participant benefited most from using the reading pen, that participant also indicated the lowest degree of satisfaction with the experience. The three studies (Bolt et al., 2011; Holmes & Silvestri, 2012; Shinn & Ofiesh, 2012) also had a diversity of findings. Focusing on 14 accommodations of interest, Bolt and colleagues (2011) indicated that the most frequently-used accommodation for a group of postsecondary students was extended time; they indicated that they also used the accommodation most often in high school.

In a literature review, Holmes and Silvestri (2012) reported that software programs used during computerized assessments in reading provided supports such as text-to-speech, optical character recognition (OCR), and synthesized speech, and computerized writing assessments supported students with speech- or voice-recognition, word prediction, and mind mapping and outlining. Shinn and Ofiesh (2012) described both universal design and accommodations solutions for postsecondary students; to address access demands, they identified font size and text-to-speech software, among others; to address output demands, extended time, word processing and keyboard composition via computer access, and dictation software. Finally, Posey and Henderson (2012) reported that reading skills constructs were essentially the same for students with visual impairments using contracted braille during an assessment as they were for students without disabilities not using accommodations, in that both groups achieved similar results. (See Appendix F, Table F-10 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

Table 14. Summary of Research Findings on Accommodations at the Postsecondary Level

Study Findings |

Number of Studies |

Postsecondary student performance |

4 |

Postsecondary faculty perceptions |

4 |

Postsecondary student perceptions |

3 |

Postsecondary accommodations practices/uses |

3 |

Postsecondary accommodations validity |

1 |

Accommodations by Academic Content Assessments

As in the previous report, we analyzed findings according to academic content area that was the focus of the research. Employing this approach recognized that many accommodations are associated with specific academic content. Some examples of these cases include: calculators for math and science assessments, and word processing for writing assessments or constructed responses on reading, other English language arts (ELA) assessments, and science assessments. Some accommodations, such as oral delivery, may be presented differently depending on the academic construct being assessed.

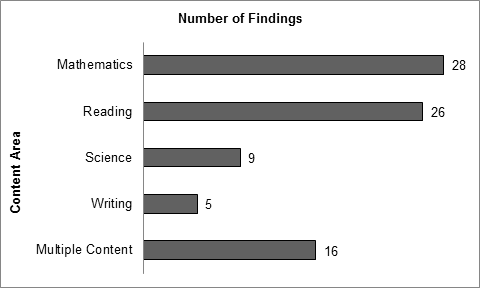

We present findings for each content area here according to the frequency with which the content areas were identified in the set of 49 research studies reviewed, with most prevalent content areas presented first: 28 findings from 20 studies in mathematics, 26 findings from 15 studies in reading, 9 findings from 3 studies in science, and 5 findings from 4 studies in writing (see Figure 4). Analysis of findings for each content area are the same as those we employed earlier in this report, including the impact of accommodations on assessment performance, perceptions about accommodations, construct validity of accommodated assessments, and matters of implementation and instances of use of accommodations.

Figure 4. Research Findings by Content Area

Note: The number of findings does not equate with the number of studies, because many studies reported more than one finding.

Mathematics. Table 15 displays the 28 research findings for accommodations from 20 studies of mathematics assessments, organized according to research type and participant populations then sorted by frequency according to the nature of the individual findings. The findings were diverse, represented by small numbers of studies for each finding, and with little agreement across the findings. Effects of accommodations on performance comprised the most frequent type of finding, with 12 findings from 11 studies. Eleven different effects of accommodations or modifications were reported in these 12 findings; calculator use was the only accommodation reported in more than one finding. The 10 accommodations were: voice-input speech-output calculator, American sign language (ASL), oral delivery, basic functions calculator, computerized format, visual chunking representation, math resource guides, extended time, various and multiple accommodations, and unique accommodations packages; and the one modification was: shortening the item stem.

Of the 12 findings, 7 of them pertained to effects for students with disabilities, and 5 pertained to effects for all students. The most common individual finding, supported by three studies, was that accommodations did not facilitate improved test performance in math for students with disabilities; this was found for voice-input speech-output calculator (Bouck et al., 2011), various and multiple accommodations (Cawthon, Kaye, Lockhart, & Beretvas, 2012), and ASL (Cawthon et al., 2011). Another finding, supported by two studies, indicated that accommodations—including oral delivery (Lazarus et al., 2012) and basic calculator (Scarpati et al., 2011)—had mixed results for students with disabilities, supporting score improvements for some items and not for other items. The last finding supported by more than one study was that accommodations, including basic calculator (Engelhard, Fincher, & Domaleski, 2011) and computerized format with online-delivered accommodations (Patterson et al., 2011), did not support math score improvements for either students with or without disabilities. The remaining five findings were unique to one study each, and not supported by other studies; two of these findings pertained to effects for students with disabilities, and three findings pertained to effects for all students (See Appendix F, Table F-11 for details of the individual study findings.)

Perceptions of accommodations used during math assessments comprised another set of findings; these six findings were identified in six different studies. Although these findings were categorized by whose perceptions were examined—students or educators, or both, most of the findings (n=4) indicated that the various accommodations were perceived as beneficial to students in terms of their math assessment performance (n=2; Beddow, 2011; Lazarus et al., 2012) or had some other benefit beside math score (n=2; Patterson et al., 2011; Hodgson et al., 2012). The other two findings indicated that students expressed preferences for one version of an accommodation (Zhang, Ding, Stegall, & Mo, 2012) or set of accommodations (Flowers et al., 2011) over a different accommodation or set. The enhancements reported in these six perception findings numbered five in all, and included accommodations such as oral delivery (in 2 studies; Lazarus et al., 2012; Hodgson et al., 2012), computerized format with online-delivered accommodations (Patterson et al., 2011), visual chunking representation (Zhang et al., 2012), and computerized format (Flowers et al., 2011), along with various modifications (Beddow, 2011).