Introduction

The purpose of this resource is to provide information on how to identify which English learners who may have a most significant cognitive disability are eligible to take an alternate English language proficiency (alt-ELP) assessment. Determining whether a student should take an alt-ELP assessment requires appropriately identifying the student as an English learner, determining whether the student has a significant cognitive disability (even though this is not a federal disability category), and following state assessment participation guidelines when available. This process is especially challenging because of the interrelationship between language and cognitive ability.

States and districts typically have two separate identification processes for students. There is one process for identifying English learners who are entitled to English language development (ELD) services. There is a second process for identifying children with disabilities, including those with the most significant cognitive disabilities who are eligible to take an alternate assessment based on alternate academic achievement standards (AA-AAAS) in mathematics, reading/language arts, and science, or an alt-ELP assessment. Without state guidance on how to apply these two processes in tandem, there can be variation in the percentages and characteristics of students identified as English learners with disabilities who may take an alt-ELP assessment. To provide greater consistency in implementation by states and districts, this resource offers a framework for identifying students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who are eligible to take the alt-ELP assessment, a framework that is in accordance with federal requirements and best practice.

This resource includes five sections:

- A summary of federal assessment requirements

- An overview of what is known about the characteristics of students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, English learners, and English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities

- A framework for identifying English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities who are eligible to participate in the alt-ELP assessment

- A discussion of additional considerations for ensuring that students are accurately identified and supported

- A list of resources, including publications and key organizations, that provide additional information on identifying English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities

Federal Assessment Requirements for English Learners and Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities

Several federal assessment requirements intersect when a decision is made about the assessment in which a student will participate. These include requirements that address the education of English learners in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and the education of students with disabilities in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Both ESEA and IDEA include requirements for participation in state assessments.

ESEA requires that states develop and implement English language proficiency (ELP) standards for speaking, listening, reading, and writing. States also must develop uniform statewide ELP assessments to measure the English language proficiency of all English learners in grades K-12, including those with disabilities (ESEA section 1111(b)). States may offer an alt-ELP assessment for those English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities who cannot participate in the state ELP assessment even with accommodations (34 C.F.R. § 200.6(h)(1), (5)).

IDEA first required the development of alternate assessments in 1997. IDEA and its implementing regulations include 13 disability categories, but “most significant cognitive disability” is not a disability category under IDEA.1 To receive IDEA funds, states and school districts must have in effect policies and procedures to ensure the participation of all children with disabilities in all general state and districtwide assessment programs, including assessments required under section 1111 of the ESEA, with appropriate accommodations and assessments where necessary and as indicated in their respective Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). The 2015 amendments to IDEA made by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) clarify that alternate assessments under Title I are limited to children with disabilities who are students with the most significant cognitive disabilities (IDEA section 612(a)(16)(A) and (C)). Both IDEA (Sec. 612(a)(16)(A); 34 C.F.R. § 300.160) and ESEA (Sec. 1111(b)(2)(B)(vii)) require that all students with disabilities, including those who are English learners, be included in all state and districtwide assessment systems, with accommodations and alternate assessments as appropriate.

ESEA also does not define the population of students with the most significant cognitive disabilities, but under Title I Part A regulations, the identification cannot be based on whether the student has a particular disability as defined in IDEA, or the student’s previous low academic achievement or need for assessment accommodations. Under these regulations, if a state adopts alternate academic achievement standards for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities and administers an alternate assessment aligned with those standards, the state must establish clear and appropriate guidelines for who should participate in an AA-AAAS. It must also monitor implementation of those guidelines for IEP teams to apply in determining, on a case-by-case basis, which students with the most significant cognitive disabilities will be assessed based on alternate academic achievement standards (34 C.F.R. § 200.6(d)(I)).

Understanding the Characteristics of English Learners with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities

Identifying a student as an English learner with a most significant cognitive disability is a necessary step in determining whether they are eligible to take the AA-AAAS or the alt-ELP assessment. If a student has previously been identified as an English learner, determined to have a most significant cognitive disability, and determined to be eligible for participation in the AA-AAAS, they are eligible to take the alt-ELP assessment. However, if a student is in grades that do not have an AA-AAAS (e.g., grades K-2), or is new to a school system and not already identified as an English learner (e.g., incoming kindergarten students, students who recently moved to the U.S.), the process for determining eligibility for the alt-ELP assessment can be more complex.

Educators often share with technical assistance providers such as the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) that they have difficulty determining when an English learner is eligible for the alt-ELP assessment because of the intersection between language learning and language-related impairments associated with some disabilities. Further, there is limited research or information available on the characteristics of English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities that educators can use to guide decisions. School personnel (e.g., educators, school psychologists, assessment coordinators) can look to related research on students with the most significant cognitive disabilities and English learners for additional insights. (For more information on this topic see Appendix A.)

Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities

States are required to provide IEP teams with guidelines for determining whether a student should participate in an AA-AAAS and to include a definition of “student with a most significant cognitive disability” in their guidelines (34 C.F.R. § 200.6 (d)(1)). State criteria for students’ participation in the alternate assessment (as well as the alternate assessments themselves) have changed over time (Quenemoen, 2009). Several multi-state studies of students who participate in AA-AAAS give insight into which students are typically considered to have the most significant cognitive disabilities. The earlier studies were conducted by Kearns and colleagues (e.g., Kearns et al. 2011; Towles-Reeves et al., 2009) and later studies were reported by the federally-funded alternate assessment consortia charged with developing alternate assessments of reading/language arts and mathematics (Nash et al., 2016; Thurlow et al., 2016).

Some students enter the K–12 school system already having been identified by medical professionals as having a disability that may be considered to be a most significant cognitive disability. These students possibly have received services for their disability from birth or early childhood. Some children are identified later through a process that involves referral for an evaluation to determine whether the student has a disability that requires special education services. Although alternate assessment participation is not limited to children that may fall under specific disability categories, the majority of students who participate in the AA-AAAS have intellectual disabilities, autism, and multiple disabilities (Christensen et al., 2018; Karvonen & Clark, 2019; Nash et al., 2016).

State AA-AAAS participation guidelines should include a definition of a student with a most significant cognitive disability and indicate how districts should identify these students, yet not all states have included a definition. According to Thurlow et al. (2019), all states had guidelines for the participation of students with the most significant cognitive disabilities in AA-AAAS, but just 36 states had an explicit definition in 2019 of “students with the most significant cognitive disabilities.”

The most common criteria in states’ guidelines were: (a) student has a significant cognitive disability and significant delays in adaptive behavior; (b) student requires intensive and extensive individualized instruction and substantial supports to access the curriculum; and (c) student is taught grade-level general education content and essential embedded skills using specially-designed instruction to meet individual needs related to the student’s disability (Thurlow et al., 2019). The most common factors that states’ guidelines indicated were not to be used as a basis for placing a student in the AA-AAAS were as follows: (a) disability label, placement, or service; (b) social, cultural, linguistic, or environmental factors; and (c) excessive absences. Instead, the most frequently mentioned criteria for participation of all students in AA-AAAS across the 50 states and the District of Columbia were: significantly affected cognitive and adaptive function (N=50); extensive individualized instruction or supports (N=49); alternate or modified curriculum standards (N=49); has disability or IEP (N=49); and parent is informed (N=26). Examples of sources of evidence for making this determination include:

- Results of individual cognitive ability tests; adaptive behavior assessments; individual and group-administered achievement tests; informal assessments; individual reading assessments; districtwide alternate assessments; language assessments, including ELP assessments, if applicable

- Instructional objectives and work samples from both school- and community-based instruction

- Present levels of academic and functional performance, goals, and objectives from the IEP

- Data from scientific research-based interventions

- Progress monitoring data

- Teacher-collected data and checklists

- Transition plan for students age 16 and older unless state policy or the IEP team determines a younger age is appropriate

Despite the consistency in states’ guidelines for districts to use in determining whether a student has a most significant cognitive disability and should participate in the state’s AA-AAAS, and the variety of decision-making forms they provide to aid in making the decision, the implementation of these guidelines in practice has proven difficult. Factors such as considerable student diversity (e.g., communication skills, linguistic and cultural background), educator subjectivity, educator familiarity with students with significant cognitive disabilities, parent desires, pressure from school administrators, and lack of IEP team awareness of the state AA-AAAS participation criteria, may exacerbate the difficulty in applying guidelines consistently (Cho & Kingston, 2015; Musson et al., 2010; Streagle & Scott, 2015; Woodall, 2020).

Researchers have demonstrated that some students in the past have been inappropriately assigned to the AA-AAAS (Cho & Kingston, 2011). (However, there is a dearth of published research following this study, which predated the Title I, Part A regulations on the factors that must be used to determine whether a child with a disability can be considered a student with a most significant cognitive disability.) In addition, data reveal a steady increase in participation rates in the AA-AAAS (averaged across the 50 states and the District of Columbia) of 0.8 percent in school year 2007–08 to 1.2 percent in school year 2016–17 in both reading/language arts and mathematics (Wu et al., 2019).

English Learners

English learners are students who are not proficient in English and are therefore eligible for ELD services. It is helpful to understand the typical process for identifying students as English learners to highlight the challenges associated with identifying students with the most significant cognitive disabilities as English learners.

The term “English learner” is defined as “an individual (A) who is aged 3 through 21; (B) who is enrolled or preparing to enroll in an elementary school or secondary school; (C)(i) who was not born in the United States or whose native language is a language other than English; (ii)(I) who is a Native American or Alaska Native, or a native resident of the outlying areas; and (II) who comes from an environment where a language other than English has had a significant impact on the individual’s level of English language proficiency; or (iii) who is migratory, whose native language is a language other than English, and who comes from an environment where a language other than English is dominant; and (D) whose difficulties in speaking, reading, writing, or understanding the English language may be sufficient to deny the individual — (i) the ability to meet the challenging State academic standards; (ii) the ability to successfully achieve in classrooms where the language of instruction is English; or (iii) the opportunity to participate fully in society.” ESEA § 8101(20).

Federal law requires that “all students who may be English learners are assessed for such status within 30 days of enrollment in a school in the state” (ESEA § 3113(b)(2)). The identification of students as potential English learners typically begins with the use of a home language survey (HLS) (Bailey & Kelly, 2012) that is completed by the student’s parent or guardian. If the HLS indicates that a language other than English is primarily used at home, an ELP screening assessment (“screener”) is then administered to determine the student’s level of English proficiency. Those students who take a screener and score below a state-established score are classified as English learners and therefore are eligible for ELD services.

English Learners with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities

To address the challenges associated with identifying an English learner who may participate in an alt-ELP assessment, it is helpful to understand what we know about English learners with disabilities and English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities who have been identified to take the state AA-AAAS.

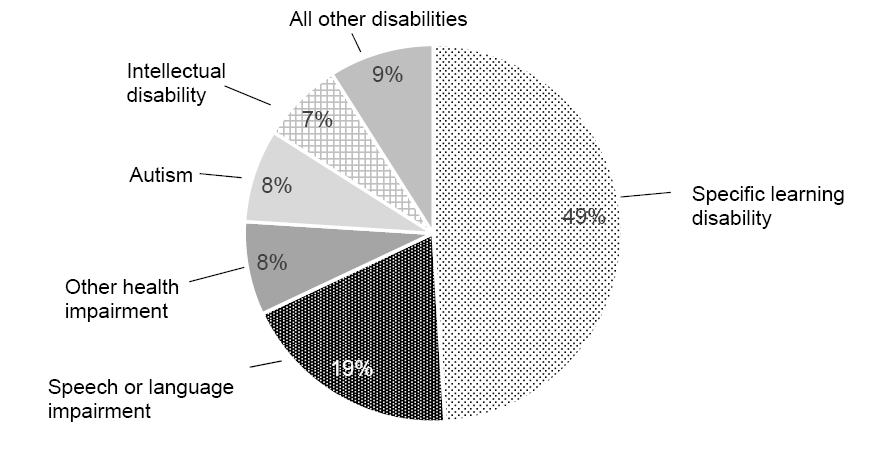

Most of the literature about English learners with disabilities does not specifically address English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities (National Center on Educational Outcomes, 2020). Although disability category is not to be used to determine who may need to participate in an AA-AAAS, typically students with intellectual disabilities, autism, or multiple disabilities are those most often identified to participate in an AA-AAAS. Thus, examining the disability categories of the population of English learners with disabilities provides some insight into how many of these students potentially may have significant cognitive disabilities (see Figure 1).

The population of English learners is neither homogeneous nor static. For example, English learners in the United States speak more than 400 languages (U.S. Department of Education, 2018). Spanish speakers are approximately three-fourths of identified English learners; however, there are sizeable populations of Arabic, Chinese, Vietnamese, Somali, Russian, Hmong, Haitian Creole, and Portuguese speakers in the United States. Further, there are different types of English learners, such as long-term English learners, newcomers, and English learners with disabilities. The population of English learners also is constantly changing as new students are classified and others reclassified as proficient in English.

Figure 1. Primary Disability Categories Under Which English Learners With IEPs, Ages 6–21, Received Services in 2017–18

<

<

Note: Data are from Child Count and Educational Environments 2017–18 (U.S. Department of Education, 2020). Percentages have been rounded and do not sum to 100 percent. Other disabilities combined include deaf blindness (less than 0.02 percent), developmental delay (2.7 percent), emotional disturbance (1.9 percent), hearing impairments (1.4 percent), multiple disabilities (1.2 percent), orthopedic impairments (0.8 percent), traumatic brain injury (0.3 percent), and visual impairments (0.3 percent).

Figure 1 shows the percentages of English learners with primary disabilities in the categories most often included in the AA-AAAS: intellectual disabilities (7 percent of English learners with disabilities), autism (7 percent of English learners with disabilities), and multiple disabilities (1.2 percent of English learners with disabilities). Given that only some of the English learners in those categories would be considered to have the most significant cognitive disabilities, the approximate numbers of students eligible for an alt-ELP assessment appear to be quite small.

State guidelines, as well as those published by multi-state assessment consortia, have recently started to include criteria for the determination of whether an English learner has a most significant cognitive disability (see Appendix A, Table A-2).

- The English Language Proficiency Assessment for the 21st Century (ELPA21) is currently developing an alt-ELP assessment, but has a white paper on English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities that includes a proposed decision making flowchart (ELPA21, 2020). Proposed criteria include student identification as an English learner, enrollment in a grade included in statewide content assessments, and participation (or expected participation) in an AA-AAAS for reading, math, or science.

- WIDA provides considerations for determining alt-ELP assessment participation in its 2019-2020 Accessibility and Accommodations Supplement (WIDA, 2019). These guidelines mention that students who are unable to take the regular ELP test with accommodations should be considered for the alt-ELP assessment, but refer educators to the alt-ELP assessment participation guidelines of their specific state education agency.

- Some, but not all, states provide information on determining an English learner’s participation in the AA-AAAS. For example, the departments of education in Arkansas (2018), Indiana (2018), Kentucky (2017), Maine (2018), Maryland (2017), and South Dakota (2019) specify that linguistic and sociocultural factors should be taken into account when assessing the evidence used in determining whether an English learner should take the AA-AAAS in the content areas.

A synthesis of the literature on English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities provides information on the characteristics of such students. Karvonen and Clark (2019) explored the characteristics of English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities in 16 states. Christensen et al. (2018) conducted a similar survey in 29 states. Both studies found that English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities (those participating in states’ AA-AAAS) tended to have the following characteristics:

- Identified as having intellectual disabilities, autism, or multiple disabilities

- Represented many home languages, with Spanish the most prevalent

- Used speech or speaking to communicate, with most others using communication supports such as picture cards or communication boards

It is also important to note that English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities must be offered appropriate ELD services. However, the Karvonen and Clark (2019) and Christensen et al. (2018) studies found data indicating that a significant number of these students did not receive legally required ELD services.2

Assessment requirements for English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities under ESEA provide an opportunity to refine state policy and local practice to more accurately identify these students and ensure that they are receiving the supports they need.

Framework for Identifying English Learners with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities Who May Participate in an alt-ELP Assessment

With the potential overlap of language learning and language-related disabilities, it can be difficult to determine which English learners with disabilities require an alt-ELP assessment. States must have valid and reliable means of identifying English learners to provide students with ELD services and to appropriately assess their English language proficiency annually, as required by ESEA. At the same time, states must have valid and reliable means of identifying students with disabilities to provide students with appropriate special education services as required by IDEA.

Federal regulations require that states provide “clear and appropriate guidelines for IEP teams to apply in determining, on a case-by-case basis, which students with the most significant cognitive disabilities will be assessed based on alternate academic achievement standards” (34 C.F.R. § 200.6 (d)(1)). The professional judgment and expertise of the IEP team is critical to making appropriate determinations. If an IEP team is determining whether a potential English learner has a most significant cognitive disability, then it is critical that the IEP team include practitioners with ELD expertise.

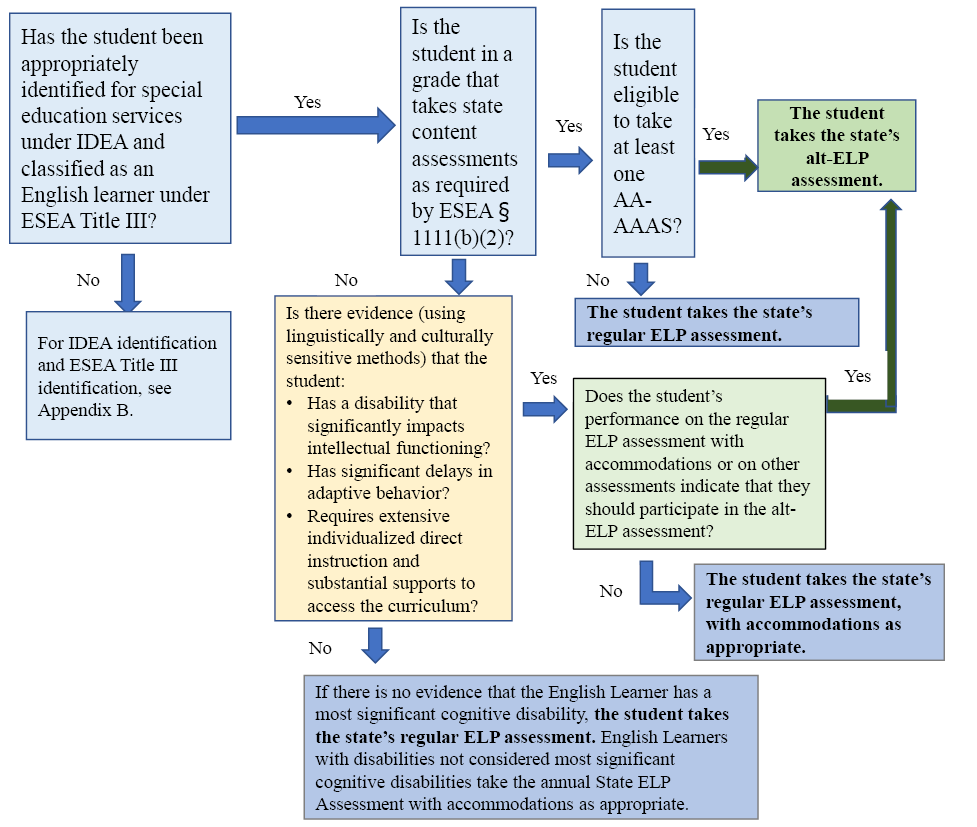

To make accurate decisions about alt-ELP assessment participation for English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities, educators need clear guidance on the specific decision points involved in the process. States may provide these decision points through guidelines on participation in the alt-ELP; IEP teams should use those guidelines to determine assessment participation if they exist.

If state guidelines do not exist, the framework (see Figure 2) and associated guiding questions included in this resource can be used by educators to clarify the process for determining participation by English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities in an alt-ELP assessment. This decision tree is based on federal regulations and includes guiding questions informed by best practice identified through technical assistance efforts. It is important to note that due to the complexity of identification and alternate assessment decisions, educators using the framework should use professional judgment along with valid and reliable measures.

Determining whether a student should take an alt-ELP assessment requires appropriately identifying the student as an English learner and a student with a disability (see Appendix B). The decision tree in Figure 2 assumes that the appropriate steps outlined in Appendix B have been taken.

Figure 2. Framework for Identifying Students Eligible for Alt-ELP Assessment Participation

Guiding Questions to Use With the Framework

If the student has been identified as a student with a disability who is eligible for special education and related services and also has been identified as an English learner (see Appendix B for more on the process for making these identifications), the key decision-making steps depend on the grade of the student.

If in a grade that has state content assessments, ask:

- Does the student participate in at least one of the state’s AA-AAAS?

If an IEP team has already determined that a student should participate in the AA-AAAS in the content areas, the student should also be considered eligible to participate in the alt-ELP assessment if they are an English learner and they cannot take the regular ELP assessment even with accommodations. It is important to note that there may be some cases in which a student is considered eligible to take the AA-AAAS but takes the regular academic content assessments based on the election of their parents or guardians and on the recommendation of their IEP team. For instance, parents or guardians of a younger student (e.g., a third grader) may elect to wait to see whether accommodations offer sufficient supports for them to participate in typical state mathematics and reading/language arts assessments. In cases where a student is determined to be eligible but does not yet elect to take the AA-AAAS, the student is also likely eligible to take the alt-ELP assessment but may elect to take the ELP assessment with accommodations. These decisions on which alternate assessments to take should be made with consideration of the individual’s context (and whether they are in a tested grade) rather than by a rigid set of decision criteria. If the student is in grades K–2, a determination that the student should participate in the alt-ELP assessment is based on consideration of their disability-related characteristics (i.e., the same characteristics used to determine AA-AAAS participation in grades 3–8 and high school) and their prior experiences taking the regular ELP assessment with accommodations.

If the answer to this question is “yes,” the student may be considered to participate in the alt-ELP assessment.

If in a grade that does not have state content assessments, determine whether the student has the characteristics of a student with the most significant cognitive disabilities by asking:

- Does the student have a disability that significantly impacts intellectual functioning?

A medical diagnosis may be made during infancy or early childhood that indicates a significant cognitive disability. If an IEP team appropriately identifies the child as a student with a disability (and thus eligible for services) under IDEA Part B upon entering the school system using culturally and linguistically sensitive practices, the child’s IEP must be developed and implemented by the child’s third birthday.3 Similarly, at entry into the K–12 public school system and every three years after identification (and more frequently under certain circumstances), the student is re-evaluated for IDEA purposes. For some students, a referral for a special education evaluation in the early grades may prompt the initial evaluation, and if the child is found eligible for special education and related services, the initial IEP process (see 34 C.F.R. § 300.301–300.306). If it is not known whether the student has a medical diagnosis indicating the possibility of a significant cognitive disability when the student enters school, the typical referral and evaluation process for possible disabilities would take place at that time. Schools are not required to evaluate every child for possible disabilities; instead, schools only need to evaluate students who are suspected of having a disability and who may need special education or related services because of that disability.

- Does the student have significant delays in adaptive behavior?

Federal regulations4 specify that a state definition addresses “factors related to cognitive functioning and adaptive behavior.”5 A student’s adaptive behavior reflects skills across a variety of areas that allow for independent functioning, including conceptual, literacy, numeracy, and self-direction skills. Adaptive behavior may be evidenced by standardized measures, interviews, or observations.

- Does the student require extensive individualized direct instruction and substantial supports to access the curriculum?

ESEA Title I Part A assessment regulations specify that state guidelines provide that “[a] student is identified as having the most significant cognitive disabilities because the student requires extensive, direct individualized instruction and substantial supports to achieve measurable gains on the challenging state academic content standards for the grade in which the student is enrolled” (34 C.F.R. § 200.6(d)(1)(iii)). Examples of evidence of individualized instruction include classroom observations and teacher data. For possible examples of substantial supports, see the IDEA definition of “related services.”6

If the answer to all these questions is “yes,” the student may be considered to have a significant cognitive disability.

Vignettes

The following three vignettes illustrate how practitioners might apply this framework in practice. These vignettes are informed by scenarios that IEP teams and other practitioners may encounter in their districts, including an analysis of what has been reported in the literature about actual students in the field (Liu et al., 2020). These examples do not capture the full range of decisions that IEP teams may need to consider given the diversity of student characteristics and contexts.

Example 1

Ahmad, age 6, has just entered a school’s kindergarten program. He was born in the U.S. and his family is from Somalia. The primary language spoken at home is Somali; his older siblings speak English with their friends. Following the information provided in the HLS, Ahmad was given an ELP screener and has been classified as an English learner. He also has been identified as needing special education services and has an IEP. Ahmad uses a limited amount of verbal speech in Somali, with the Somali words he uses typically relating to names, colors, action words, and his likes or dislikes. However, he does have receptive language skills in Somali and can respond to oral instructions. Ahmad also has some receptive language skills in English. His mother indicates he has some difficulty socializing with other children his age and communicating his wants and needs appropriately. Ahmad’s IEP team does not think that his intellectual disability precludes him from accessing the kindergarten content because his disability does not affect his intellectual functioning in comparison to his peers. Given his age, grade level, and disability, Ahmad does not require extensive individualization of the curriculum to participate with his grade-level peers.

Decision: Ahmad takes the general state ELP assessment (not the alt-ELP assessment), and his IEP team recommends specific accommodations.

Example 2

Ling is enrolling in 10th grade at a new school in a new district. Ling’s family is from China and emigrated to the U.S. when Ling was in 7th grade. Ling has a severe intellectual disability; she communicates using a moderate amount of verbal speech in Chinese, some words in English, gestures, and a few American Sign Language signs. Ling has receptive language skills in both Chinese and English. At home, Ling can give brief verbal responses to questions or directions. At her previous school, Ling enjoyed participating in shared reading experiences with her teacher and learned how to follow a series of steps to turn on an electronic tablet to access stories (i.e., reading/language arts materials). Ling received special education services and participated in the AA-AAAS in her previous school. Staff at Ling’s new school have a copy of the IEP from her previous school. When Ling first came to the U.S. in 7th grade, she was identified as an English learner and received ELD services at her previous school. Staff at Ling’s new school are aware that Ling is an English learner and will continue to receive ELD services; likewise, Ling will continue to participate in the AA-AAAS. Ling receives instruction aligned to the regular 10th grade content standards for reading/language arts, mathematics, science, and social studies, but at a reduced depth, breadth, and complexity. Ling’s IEP team, which includes her ELD teacher, agree that taking the regular ELP assessment with accommodations does not meet her learning needs and that she meets the criteria for participation in the alt-ELP assessment.

Decision: Ling takes the alt-ELP assessment, with accommodations recommended by the IEP team.

Example 3

Carolina is a fifth grader who has been in the U.S. for four years. She has Down syndrome and a moderate intellectual disability. Carolina has some receptive and expressive language skills in both English and Spanish, but her speech is often hard to understand. Carolina’s preferred language is Spanish and her family uses only Spanish at home. Carolina has been receiving ELD services since she arrived in the U.S. For the past four years, Carolina has been keeping up with the lower-performing peers in her general education classrooms. Although she is not currently performing at grade level, she does not need extensive individualization and supports to access the grade-level curriculum. Carolina’s 5th grade teacher is a fluent Spanish speaker and has been able to provide some native language supports in the general education classroom. This year, Carolina’s IEP team has decided to have her participate in the general assessments of reading/language arts, mathematics, and science. Carolina’s IEP team and English language education teacher agree that there are accommodations that will enable her to participate in the regular ELP assessment.

Decision: Carolina takes the regular state ELP assessment (not the alt-ELP assessment), and her IEP team recommends specific accommodations.

Additional Considerations for Identifying English Learners with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities for an alt-ELP Assessment

The identification of English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities for participation in alternate assessments is an evolving area of policy and practice. Still and Christensen (2018) described key elements for a valid, fair, and reliable alternate English language proficiency assessment system, and related policies and practices, as including:

- A theory of action that explicates the purpose of assessing English learners with significant cognitive disabilities and that identifies intended uses of the results, including how those results will inform learning opportunities for students.

- Alternate English language proficiency standards aligned to academic standards and focused on the essentials of communication at grade level.

- Performance expectations that are demonstrably comparable to those of grade-level peers who are students with cognitive disabilities and are not English learners.

- Innovative technical approaches to cognitive labs, universal design, test delivery, and measurement.

- Incorporation of additional supports, such as assistive technology devices and testing platform tools and accommodations, as well as guidance for augmented interaction by the test administrator.

- Input from educators and researchers who know English learners with significant cognitive disabilities best, and their ongoing involvement in development and delivery of the assessments. (p. 10)

Although there are promising practices for determining assessment participation, the development and use of measures and methods for this process are in the nascent stages. Educators—specifically, IEP teams—can benefit from access to (and support in using) the following:

- An alternate ELP screener that is valid and reliable for use with potential English learners with significant cognitive disabilities. Currently, there are few screeners to initially assess the English language proficiency of students who are from homes where a language or languages other than English are spoken and who also have a significant cognitive disability. Some states are in the process of developing such screeners. For example, California is developing an assessment called the Alternate ELPAC (English Language Proficiency Assessments for California) that will serve both as a screener to initially identify students with significant cognitive disabilities as English learners or as fluent English proficient, and to annually assess the progress of English learners in acquiring English language proficiency and eligibility for reclassification.7

- Measures to evaluate whether a student has a most significant cognitive disability that are valid and reliable for use with students who may be English learners. For English learners, there are very limited examples of specific measures and methods to determine whether a student should participate in a state’s AA-AAAS. These include cognitive ability assessments and adaptive behavior evaluations that have been developed in students’ native languages or that do not require language.

State educational agency leaders have made strides in developing and implementing state policies related to students with the most significant cognitive disabilities through ongoing, cross-state collaboration and peer learning. State leaders—specifically, cross-divisional teams including staff who work on issues related to English learners, students with disabilities, and assessment and accountability—can benefit from opportunities to collaborate with other states to address the challenges related to English learners highlighted in this resource. Collaboration opportunities may include the development and deployment of additional valid and reliable alternate ELP screeners, measures to evaluate whether an English learner has a most significant cognitive disability, and the policies and practices that would enable these students to reach their full potential.

Conclusion

Some states and ELP assessment consortia have developed, or are in the process of developing, alt-ELP assessment participation criteria that identify English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities. However, not all states currently have such criteria. At the present time, some states may only have AA-AAAS participation criteria that are not specific to English learners taking ELP assessments. To provide greater consistency in alt-ELP participation decision making by states and districts, this resource provides a framework in accordance with federal requirements and best practice.

References

Arkansas Department of Education. (2018). Guidance for IEP teams for participation decisions for the Arkansas Alternate Assessment Program. http://dese.ade.arkansas.gov/public/userfiles/Learning_Services/Student%20Assessment/DLM/

Guidance_for_IEP_Teams_on_Alternate_Assessment_2018-2019.pdf

Bailey, A, L., & Kelly, K. R. (2012). Home language survey practices in the initial identification of English learners in the United States. Educational Policy, 27(5), 770–804.

Cho, H., & Kingston, N. (2011). Capturing implicit policy from NCLB test type assignments of students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 78(1), 58–72.

Cho, H. J., & Kingston, N. (2015). Examining teachers’ decisions on test-type assignment for statewide assessments. The Journal of Special Education, 49(1), 16–27.

Christensen, L, L., Mitchell, J. D., Shyyan, V. V., & Ryan, S. (2018). Characteristics of English learners with significant cognitive disabilities: Findings from the Individual Characteristics Questionnaire. Alternate English Language Learning Assessment (ALTELLA). http://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ICQ-Report.pdf

Educational Testing Service. (2016). The road ahead for state assessments: What the assessment consortia built, why it matters, and emerging options. https://www.ets.org/s/k12/pdf/coming_together_the_road_ahead.pdf

Educational Testing Service. (2019). Proposed high-level test design for the Alternate English Language Proficiency Assessments for California. https://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/ep/documents/proposedhltdaltelpac.pdf

ELPA21. (2020). English Language Proficiency Assessment for the 21st Century (ELPA21).

https://educateiowa.gov/pk-12/learner-supports/english-learners/english-language-proficiency-assessment-21st-century-elpa21

Indiana Department of Education. (2018). Participation decision for Indiana’s Alternate Assessment frequently asked questions. https://www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/assessment/indiana-alternate-assessment-participation-guidance-faq-final-3-28-18.pdf

Karvonen, M., & Clark, A. K. (2019). Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who are also English learners. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 44(2), 71–86.

Kearns, J. F., Towles-Reeves, E., Kleinert, H. L., Kleinert, J. O., & Thomas, M. K. (2011). Characteristics of and implications for students participating in alternate assessments based on alternate academic achievement standards. Journal of Special Education, 45, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022466909344223

Kentucky Department of Education. (2017). Guidance for Annual Review Committees (ARCs) on participation decisions for the Kentucky Alternate Assessment. https://www.hdilearning.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Guidance-for-Annual-Review-Committees-ARCs-on-Participation-Decisions-for-the-Kentucky-Alternate-Assessment.docx

Liu, K. K., Thurlow, M. L., & Dosedel, M. J. (2020). A literature review of evidence-based literacy assessment and instruction practices for English learners with significant cognitive disabilities (NCEO Report 422). National Center on Educational Outcomes. https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/NCEOReport422.pdf

Maine Department of Education. (2018). Guidance for IEP teams on participation decisions for Maine’s Alternate Assessments. https://www.maine.gov/doe/sites/maine.gov.doe/files/inline-files/Maine%20Participation

%20Guidance_Rev%2012-28-18_0.pdf

Maryland State Department of Education. (2017). Maryland guidance for IEP teams on participation decisions for the alternate assessments. http://marylandpublicschools.org/programs/Documents/Special-Ed/TAB/Alternate

AssessmentParticipationGuide.pdf

Minnesota Department of Education. (2018). English learner companion to promoting fair evaluations. https://education.mn.gov/MDE/dse/sped/div/el/MDE087755

Musson, J. E., Thomas, M. K., Towles-Reeves, E., & Kearns, J. F. (2010). An analysis of state alternate assessment participation guidelines. The Journal of Special Education, 44(2), 67–78.

Nash, B., Clark, A. K., & Karvonen, M. (2016). First contact: A census report on the characteristics of students eligible to take alternate assessments (Technical Report No. 16-01). Center for Educational Testing and Evaluation.

https://dynamiclearningmaps.org/sites/default/files/documents/publication/First_Contact_Census_2016.pdf

National Center on Educational Outcomes. (2020). ELs with disabilities.

https://nceo.info/student_groups/els_with_disabilities

Quenemoen, R. F. (2009). The long and winding road of alternate assessments: Where we started, where we are now, and the road ahead. In W. D. Shafer & R. W. Lissitz (Eds.), Alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards: Policy, practice, and potential (pp. 127–153). Paul H. Brookes.

South Dakota Department of Education. (2019). Guidance for IEP teams on participation decisions on the Alternate Assessment of South Dakota Content Standards. https://doe.sd.gov/assessment/documents/Alt-Guidelines-19.pdf

Still, C., & Christensen, L. L. (2018). Talking points for state leaders: Alternate English language proficiency standards and assessments (ALTELLA Brief No. 8). Wisconsin Center for Education Research.

https://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ALTELLA_Brief-08_Talking-Points-State-Leaders.pdf

Streagle, K., & Scott, K. W. (2015). The alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards eligibility decision-making process. The Qualitative Report, 20(8), 1290.

Thurlow, M. L., Lazarus, S. S., Albus, D. A., Larson, E. D., & Liu, K. K. (2019). 2018–19 participation guidelines and definitions for alternate assessments based on alternate academic achievement standards (NCEO Report 415). National Center on Educational Outcomes. https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/NCEOReport415.pdf

Thurlow, M. L., Wu, Y.-C., Quenemoen, R. F., & Towles, E. (2016). Characteristics of students with significant cognitive disabilities (NCSC Brief No. 8). National Center and State Collaborative. http://www.ncscpartners.org/Media/Default/PDFs/Resources/NCSCBrief8.pdf

Towles-Reeves, E., Kearns, J., Kleinert, H., & Kleinert, J. (2009). An analysis of the learning characteristics of students taking alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards. Journal of Special Education, 42(4), 241–254.

U.S. Department of Education. (2018). A state’s guide to the U.S. Department of Education’s assessment peer review process. U.S. Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/account/saa/assessmentpeerreview.pdf

United States Department of Education. (2020). IDEA Section 618 data products: State level data files. https://www2.ed.gov/programs/osepidea/618-data/state-level-data-files/index.html#bccee

WIDA. (2019). Accessibility and accommodations supplement.

https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/ACCESS-Accessibility-Accommodations-Supplement.pdf

Woodall, C. M. (2020). Problem of practice: Impact of staff training on identification rates of students with disabilities in statewide alternate assessments. (Publication No. 27830878) [Doctoral dissertation, Wilmington University (Delaware)]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Wu, Y. C., Thurlow, M. L., Albus, D. A., & Liu, K. K. (2019). Trends in AA-AAAS participation and performance for 2007–08 through 2016–17 (NCEO Data Analytics 12). National Center on Educational Outcomes.

https://tableau.ahc.umn.edu/t/ICI/views/AA-AAStrend0708-1617/Story1

Related Resources

Publications

The following publications provide additional information related to identifying English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities.8

State Policy Analysis

- 2018–19 Participation Guidelines and Definitions for Alternate Assessments based on Alternate Academic Achievement Standards (cited as Thurlow et al, 2019):

https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/NCEOReport415.pdf - Guidance Manuals for English Learners with Disabilities:

https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/west/Ask/Details/68 - Voices from the Field: State Assessments for ELLs with Disabilities:

https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/IVAREDFocusGroupReport.pdf

English Learners With Significant Cognitive Disabilities

- Characteristics of English Learners with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: Findings from the Individual Characteristics Questionnaire:

https://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ICQ-Report.pdf - English Learners with Disabilities: Shining a Light on Dual-identified Students (cited as Christensen, Mitchell, Shyyan, and Ryan, 2018):

https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/english-learners-disabilities-shining-light-dual-identified-students/introduction/ - Establishing a Definition of English Learners with Significant Cognitive Disabilities:

http://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ALTELLA_report_Definition%20050318.pdf - Students with the Most Significant Cognitive Disabilities Who Are Also English Learners (cited as Karvonen and Clark, 2019):

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1540796919835169?journalCode=rpsd - White Paper on English Language Learners with Significant Cognitive Disabilities (cited as Thurlow et al, 2016):

https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/AAATMTWhite%20Paper.pdf

Alternate English Language Proficiency Standards and Assessments

- Alternate ACCESS for ELLs Participation Criteria Decision Tree:

https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/Alt-Access-Participation-Criteria-Diagram.pdf - Alt-ELPA21 Participation Guidelines:

https://elpa21.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Alt-ELPA21-Participation-Guidelines.pdf - Examining Relationships Between Alternate ACCESS and State Alternate Assessments: Exploring Notions of English Language Proficiency:

https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/Report-ExaminingRelationshipsBetweenAlternateAccessandStateAlternateAssessmentsAL.pdf - Exploring Alternate ELP Assessments for ELLs with Significant Cognitive Disabilities:

https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/briefs/brief10/NCEOBrief10.pdf - Talking Points for State Leaders: Alternate English Language Proficiency Standards and Assessments (cited as Still and Christensen, 2018):

https://altella.wceruw.org/pubs/ALTELLA_Brief-08_Talking-Points-State-Leaders.pdf

Practitioner Supports and Considerations

- Educators’ Thoughts on Making Decisions About Accessibility for ALL Students:

https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/DIAMONDFocusGroupReport.pdf - Framework on Supporting Educators to Prepare and Successfully Exit English Learners with Disabilities from EL Status:

https://ccsso.org/resource-library/ccsso-framework-supporting-educators-prepare-and-successfully-exit-english - Classroom Perspectives on English Learners with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: http://altella.wceruw.org/resources.html

- Considerations for Educators Serving English Learners with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: http://altella.wceruw.org/resources.html

Key Organizations

Technical Assistance Providers

National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO): https://nceo.info/

NCEO focuses on the inclusion of students with disabilities, English learners, and English learners with disabilities in comprehensive assessment systems. This includes issues related to accessibility during formative assessment, non-summative assessments (e.g., classroom-based assessments, interim/benchmark assessments), and summative assessments.

The National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) provides technical assistance to states through several activities:

- One Percent Community of Practice (CoP)—44 states participate on a biweekly basis in this CoP hosted by NCEO. The CoP allows states to talk to each other. It has a password-protected platform with shared workspace so that state participants can have discussions and share resources among themselves.

- One Percent National Convening—Nearly 200 participants from 47 states met in Boston in October 2018 to begin to develop action plans for their one percent threshold work.

- Peer Learning Group (PLG) 1 (Digging Into Your Data: Building a 1% Data Analysis and Use Plan)—25 states participated in PLG 1 February–April, 2019.

- PLG 2 (Guiding and Evaluating District Justifications for Exceeding the 1% Cap)—41 states participated in PLG 2 June–August 2019.

- PLG 3 (Building Capacity of IEP Teams and Parents in Making Decisions about Assessment Participation)—48 states participated in PLG 3 October–December 2019. Three workgroups were formed during this PLG, focusing on information to provide to (a) school administrators, (b) school personnel, and (c) parents.

TIES Center: https://tiescenter.org/

The TIES Center is the national technical assistance center on inclusive practices and policies. It works with states, districts, and schools to support the movement of students from less inclusive to more inclusive environments. TIES stands for Increasing (T)ime, (I)nstructional Effectiveness, (E)ngagement, and State (S)upport for Inclusive Practices.

National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition (NCELA): https://ncela.ed.gov/

NCELA collects, coordinates, and conveys a broad range of research and resources in support of an inclusive approach to high quality education for English learners.

Other Related Initiatives

Alternate English Language Learner Assessment (ALTELLA): http://altella.wceruw.org/

The ALTELLA project aims to apply lessons learned from research on successful instructional practices, accommodations, and assessing English learners and students with cognitive disabilities to inform alternate English language proficiency assessments.

AA-AAAS Consortia

Dynamic Learning Maps (DLM) and Multi-State Alternate Assessment (MSAA) comprise the two federally-funded assessment consortia for alternate assessments for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities.9 Originally awarded in 2010 to the DLM Alternate Assessment Consortium and the National Center and State Collaborative (NCSC), these assessments are aligned to college and career readiness standards (Educational Testing Service 2016). With the ending of the NCSC grant, funding has transitioned to the MSAA Consortium. These consortia have developed both summative and nonsummative computer-based assessments, instructional resources, and aligned professional development based on college and career readiness standards.

DLM Alternate Assessment:10 https://dynamiclearningmaps.org/

MSAA:11 https://www.msaaassessment.org (Also see the website for the former NCSC for historical information: http://www.ncscpartners.org/.)

ELP Assessment Consortia

ELPA21 and WIDA comprise the two federally funded assessment consortia for ELP assessments used to measure English proficiency of English learners. Similar to the AA-AAAS consortia, these consortia have developed both summative and nonsummative computer-based assessments, instructional resources, and aligned professional development based on college and career readiness standards (Educational Testing Service 2016). These consortia are in the process of either developing or revising alternate English language proficiency assessments.

ELPA21: https://www.elpa21.org/

WIDA: https://wida.wisc.edu/

Appendix A: Alternate Assessment Participation Guidance

Table A-1. Alternate Assessments Based on Alternate Academic Achievement Standards (AA-AAAS) Participation Guidelines

Note: Guidance on AA-AAAS participation was found by conducting searches on each state educational agency website using the following search terms: “alternate,” “participation guidelines,” “participation criteria,” and “significant cognitive disability.” Guidance was compiled in December 2019.

Table A-2. Alt-ELP Assessment Participation Guidance

Note: Guidance on alt-ELP assessment participation was found by conducting searches on each state educational agency website using the following search terms: “alternate,” “participation guidelines,” “participation criteria,” “significant cognitive disability,” and “ELP.” Guidance was compiled in December 2019.

Appendix B: Processes for ESEA Title III and IDEA Identification

fig01

Is the student an English learner?

Two guiding questions accompany this decision point.

1. Does the home language survey indicate that a student’s primary or home language is a language other than English? Students who may be English learners must be assessed for English learner status within 30 days of first enrolling in school (ESEA § 3113(b)(2)). A home language survey (HLS) is the most common tool used for initial identification of potential English learners.12 If a student enrolling in a new school has already been previously identified as an English learner, the student does not necessarily have to be assessed to be identified as an English learner in their new school. It is important to note that while an HLS is most likely administered early in the school year, the determination of whether an English learner takes the ELP assessment or the alt-ELP assessment does not have to be made until shortly before testing occurs (i.e., in the spring or winter, depending on state assessment timing).13

2. Does the student score below proficient on an ELP screener that has been validated for the intended population, indicating that the student may be an English learner? Another typical step in the English learner identification process is the use of an ELP screener. Not all states have screeners appropriate for English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities.

Is the student considered to need special education services?

IDEA requires that a child suspected of having a disability be referred for an evaluation. The evaluation assesses the areas related to the child’s suspected disability (e.g., academic achievement, behavior, etc.). Results from the assessment are reviewed by professionals and parents to decide whether the child is eligible for special education and related services. If it is decided the child is eligible for special education services, an IEP team is established to write an IEP for the child.

In practice, the two major decision points (whether the student is an English learner and whether the student is considered to have a disability) interact and inform one another. These decisions should be made through thoughtful consideration of all evidence and on an individual basis, with professionals who have the relevant expertise.

Promising Practice: Processes That Differentiate Between Disability and Language Proficiency

A key challenge in identifying English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities is the difficulty with differentiating between student characteristics that stem from cognitive disabilities—including communication disorders—and student characteristics that stem from the development of English language proficiency. The processes that IEP teams use to determine whether a student has a most significant cognitive disability should be valid and reliable for use with that student, including with a student who is or may be an English learner. Although we were unable to locate specific measures for assessing significant cognitive disability that are valid and reliable for use with English learners, some states have provided detailed guidance to IEP teams to reduce bias and increase the fairness of the assessment process. For example, in the Minnesota Department of Education’s English Learner Companion to Promoting Fair Evaluations, the state provides a set of principles and a framework for conducting intellectual assessment of English learners (Minnesota Department of Education, 2018).

Footnotes

1 The 13 disability categories in IDEA and its implementing regulations are autism, deaf-blindness, deafness, emotional disturbance, hearing impairment, intellectual disability, multiple disabilities, other health impairment, orthopedic impairment, specific learning disability, speech or language impairment, traumatic brain injury, and visual impairment (including blindness). 20 U.S.C. 1401(3) and 34 C.F.R. § 300.8.

2 The two multi-state studies documenting the results of teacher-completed surveys provide the most complete picture of students’ communication patterns and skills (Christensen et al., 2018; Karvonen & Clark, 2019). According to these studies most, but not all, English learners with the most significant cognitive disabilities consistently responded appropriately to spoken or signed phrases and sentences. Another group of students were able to respond appropriately to some spoken or signed phrases and sentences, but not others. Teachers most often believed that the students responded appropriately to communication in English, but they were not necessarily knowledgeable about students’ receptive communication skills in their native language (Christensen et al., 2018). In addition to receptive communication skills, the majority of English learners with significant cognitive disabilities in these two studies had some type of symbolic expressive communication skills. More than two-thirds of the students in both studies used spoken words to communicate. They also used picture cards, augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices, eye gaze, communication boards, sign language, and gestures. Some students used more than one type of symbolic communication. Using their preferred methods of communication, many students could put together three or more spoken words, signs, or symbols when communicating. However, fewer students in each study communicated with only single words, signs, or symbols and a small number were nonverbal.

3 Up to age 3, an individualized family service plan (IFSP) describes services needed for the infant or toddler and family under Part C of IDEA. If agreed to by the parent and school, an ISFP may serve as the IEP for the child aged three through five who is eligible for services under Part B of IDEA (34 C.F.R. § 300.323(b)).

4 34 C.F.R. § 200.6(d)(1)

5 Federal regulations on identifying students with the most significant cognitive disabilities were informed in part by the collaborative work of the state assessment consortia—Dynamic Learning Maps Alternate Assessment Consortium and the National Center and State Collaborative (now known as the Multi-State Alternate Assessment)—that were funded to develop next-generation subject area assessments for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. See Thurlow et al., 2017 for more information on the research behind identified factors.

6 Related services means “transportation and such developmental, corrective, and other supportive services as are required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education, and includes speech-language pathology and audiology services, interpreting services, psychological services, physical and occupational therapy, recreation, including therapeutic recreation, early identification and assessment of disabilities in children, counseling services, including rehabilitation counseling, orientation and mobility services, and medical services for diagnostic or evaluation purposes. Related services also include school health services and school nurse services, social work services in schools, and parent counseling and training” (34 C.F.R. § 300.34). A list of related services under IDEA is not exhaustive and could include other supportive services that are required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education.

7 According to the test design for California’s Alternate English Language Proficiency Assessment, students eligible to take the alt-ELP screener or alt-ELP assessment are: “Students with the most significant cognitive disabilities who are determined by IEP teams to be eligible for an alternate assessment in kindergarten through grade twelve; and are enrolled in California schools for the first time who are potentially [English learners] based on a home language other than English, as indicated by the results of a home language survey. Students meeting these criteria must be administered the Initial Alternate ELPAC within 30 days of their enrollment” (Educational Testing Services 2019, p. 2).

8 This document contains resources that are provided for the user’s convenience. The inclusion of these materials is not intended to reflect their importance, nor is it intended to endorse any views expressed, or products or services offered. These materials may contain the views and recommendations of various subject matter experts as well as hypertext links, contact addresses, and websites to information created and maintained by other public and private organizations. The opinions expressed in any of these materials do not necessarily reflect the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. The U.S. Department of Education does not control or guarantee the accuracy, relevance, timeliness, or completeness of any outside information included in these materials.

9 In addition to the two federally funded AA-AAAS consortia, AIR Assessment (Cambium Assessment effective January 1, 2020) supports an alternate assessment item sharing memorandum of understanding (MOU) for a group of seven states: Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, South Carolina, Vermont, and Wyoming. Each state is individually contracted with Cambium Assessment and then bound together by the MOU. The MOU defines an item development plan for each state that enables the group of states to share in an item bank that in turn supports each state’s development of its own alternate computer adaptive test.

10 States have the option to join the Consortium for both English language arts and mathematics testing, for science testing, or for all three. Current members of the DLM Consortium are Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, District of Columbia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

11 MSAA is currently being administered by nine participating states: Arizona, Maine, Maryland, Montana, the Pacific Assessment Consortium (PAC-6, which includes American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Marshall Islands, and Palau), South Dakota, Tennessee, U.S. Virgin Islands, and Washington, D.C.

12 There are no federal requirements mandating the use of an HLS to assess potential English learners. There may be local variation in the administration of home language surveys.

13 If a school or district is using paper-based assessments rather than online assessments, this decision may need to be made sooner to ensure the school or district can order the appropriate testing forms in advance.