Martha L. Thurlow, Vitaliy V. Shyyan, Sheryl S. Lazarus, and Laurene L. Christensen

December 2016

All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Thurlow, M. L., Shyyan, V. V., Lazarus, S. S., & Christensen, L. L. (2016). Providing English language development services to English learners with disabilities: Approaches to making exit decisions (NCEO Report 404). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Instructional and decision-making practices for English learners (ELs) with disabilities are garnering increased attention as the number of these students increases across the U.S. Although many critical educational decisions are made for these students, the determination that an EL with disabilities should be reclassified and exited from services is one of the more critical decisions made for individual students.

The purpose of this report is to provide a baseline report, prior to the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act, on factors that affect decisions to exit ELs with disabilities from English language development services. In this report, we review what is known about current populations of ELs with disabilities--their numbers and their language and disability characteristics. Then, we describe a survey of states that was conducted in 2015-16, and the responses to that survey. The responses of the 90% of states and DC that completed the survey indicated that some states had clear exit criteria for ELs with disabilities, although in many of those cases, the criteria for ELs with disabilities were the same as those for ELs without disabilities. Many states did not have a specific exit process or criteria for ELs with disabilities, allowing districts to establish their own criteria. Most states did not know how many ELs with disabilities exited EL services; in those states that did know, the percentages of ELs with disabilities exiting from EL services were relatively small.

The survey results suggested that many states could benefit from developing or refining their exit criteria for ELs with disabilities. These states might benefit from considering the use of multiple measures of exit readiness for these students. Further, the results suggested that it would be beneficial to use a team approach to exit decision making, with the team including both Individualized Education Program (IEP) and EL team members.

English learners (ELs) receive English language development services through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Although there are many critical decisions to be made in providing language development services to ELs, two critical decisions that have received considerable attention are: (a) the initial classification of a student as being an EL who is eligible for services, and (b) the determination that the student is no longer eligible for services and should be reclassified and exited from services (Linquanti & Cook, 2013, 2015). These decisions are complex, requiring consideration of many factors. Even more complex, according to both researchers (Abedi, 2009; Liu & Barrera, 2013; Liu, Ward, Thurlow, & Christensen, 2015) and practitioners (Liu et al., 2013) is making these decisions for ELs who also have disabilities. Especially vexing is the decision of when to exit an English learner with a disability from EL services. Federal guidance (U.S. Department of Education, 2014, 2015) indicates that ELs with disabilities can be exited from EL status only when the students no longer meet the state's definition of an EL (i.e., is proficient in English), although school personnel can have input into the decision. Little is known about how this occurs in individual states.

Before the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), many states were already proactively engaged in efforts to improve Title III program accountability and reporting systems. With the passage of ESSA, greater clarity now exists in terms of appropriate processes for determining how and when ELs with disabilities can be exited from English language development services. Specifically, under Section 3113 of the ESEA, each state educational agency (SEA) is now required to have standardized entrance and exit procedures for ELs. These procedures must include valid, reliable, and objective criteria that can be applied consistently across the state.

The purpose of this report is to provide a baseline report on several factors that have affected decisions to exit ELs with disabilities from English language development services prior to the passage of ESSA, including the relationship of these decisions to students' Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). First, we review what we know about the current populations of ELs with disabilities--their numbers and their characteristics (language characteristics and disability characteristics). Then, we describe the survey of states that we conducted in 2015-16 and the responses to that survey, including the extent to which states collect data on the numbers of ELs with disabilities exited from services. In this regard, we caution that some reported practices may not fully align with the requirements in Section 3113(b)(2) of ESEA and caution the reader not to infer program compliance from the practices included in states' responses. Still, such baseline information not only serves to document the current state of practice, but also assists in highlighting areas where additional technical assistance may be needed as well as provides the means for identifying subsequent changes in state and local policy and practice, and in measuring associated improvements over time. We conclude by discussing the implications of the survey results for practice and policy.

For many years, we had no data on the prevalence of ELs with disabilities, unless a special study was conducted to explore the numbers (Zehler et al., 2003). More recently, the Office of Special Education Programs has collected these data. An interactive summary of these data for 2012-13 by Liu, Albus, Lazarus, and Thurlow (2016) reveals that ELs with disabilities range across states from less than 1% of students with disabilities to 31% of students with disabilities ages 6-21. ELs with disabilities tend to be concentrated in states that have relatively larger populations of ELs in general, such as California, New Mexico, Nevada, Texas, and Colorado (Liu et al., 2015). There are also wide variations in the more prevalent language backgrounds of ELs across the states, even though Spanish is currently the most frequent language after English in nearly every state. For example, the second most frequent language in states varies from Arabic (in 11 states) to Vietnamese (in 5 states) to Somali (in 1 state) (Liu et al., 2016). Despite the details we have about the languages of ELs, we do not have similar data for ELs with disabilities. Until recently, there has not been publicly available information about the most frequent disability categories of ELs.

Little is known about the decision-making practices currently in place for determining whether an EL has a disability, or a student with a disability is an EL, although recent research has focused on the role that a response-to-intervention (RTI) or multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) can contribute to this decision-making process (Linan-Thompson, Vaughn, Prater, & Cirino, 2006; Rinaldi & Samson, 2008). It is important to note though that such practices may not delay evaluation for a possible disability (Office of Special Education Programs, 2011). Even less is known about the decision to exit an EL with a disability from English language development services, although some research has indicated that, at least in some states, this decision-making process is not at all clear to many practitioners (Liu et al., 2013).

To establish a baseline of where states are in terms of important exit decisions, we conducted an online survey of states. This survey asked about:

The specific questions included in the survey are presented in Appendix A.

Top of Page | Table of Contents

NCEO gathered email addresses of Title III directors for 50 states and the District of Columbia in mid-October 2015, and distributed the online survey to them in late October. Incorrect email addresses were corrected by contacting other personnel in the State Department of Education. Response reminders were sent during November and December of 2015. The majority of responses (41 of 46) were received by December 8, 2015. All responses were gathered and summarized both quantitatively and qualitatively

Top of Page | Table of Contents

Survey responses were obtained from 46 states by February 4, 2016, and the online survey was closed at that point. The 90% response rate was very high. All of the non-responding states had an above average percentage of students who were EL, and three of the non-responding states were large EL population states.

Top of Page | Table of Contents

Survey results are presented here in terms of both the quantitative responses and an analysis of the qualitative responses. State names and the names of state assessments were removed from comments included in the report; terms used by states in their comments were retained (e.g., ELLs, LEP). Results are presented for each topic surveyed.

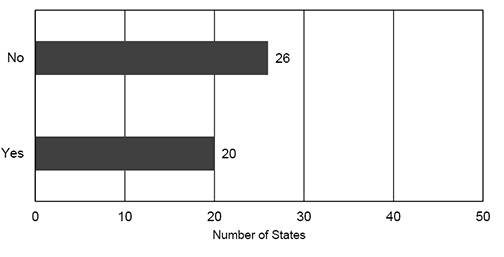

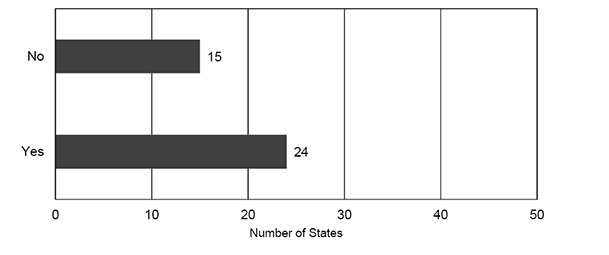

Exit of ELs with Disabilities from EL Services. States were asked to indicate whether the state provided criteria for districts to use when judging whether an EL with a disability has achieved English proficiency and is ready to be exited from EL services. More than half of the states (see Figure 1) indicated that no criteria were provided to districts.

The 20 states that responded "yes" to having criteria for exiting ELs with disabilities were asked for additional detail about the criteria. Fifteen of these states indicated that the criteria the state provided for districts to use were the same for ELs with disabilities as they were for ELs without disabilities. A few of these states mentioned that the criteria were the same for all ELs with disabilities, including those who participated in an alternate English language proficiency (ELP) assessment. One state indicated that while the criteria currently were the same for ELs and ELs with disabilities, the state was in the process of developing criteria specific to ELs with disabilities.

Figure 1. Existence of State-Provided Criteria to Districts for Districts to Use When Judging Whether to Exit ELs with Disabilities from EL Services (n=46)

Most of the 15 states indicating that they had the same criteria for districts to use in judging whether to exit ELs and ELs with disabilities reported that they used one of three approaches to determine exit from services:

In those five states that indicated they had different criteria, three states reported that there was an IEP team process for making decisions about whether an EL with a disability was proficient on the ELP assessment. Two states indicated that their criteria for ELs with disabilities used different scores or indicators for this population.

Responses to the open-ended question about the criteria for exiting ELs with disabilities from English development services were varied. Some representative responses were:

States that responded "no" to the question of whether the state provided criteria to districts specific for ELs with disabilities were asked whether they knew the criteria used in districts within the state, and if so to provide some common examples of the criteria. Twenty-five of the 26 states responded to this question. All but one of those 25 states indicated that districts used the state's criteria or followed state guidance about exit. It is assumed that these criteria were general state exit criteria, not specific to ELs with disabilities. The one state responding differently reported that districts must submit an EL plan that included the district's plans for reclassification (with the state providing guidance on who was to participate in the reclassification process). Some of the responses to the request to provide examples were the following:

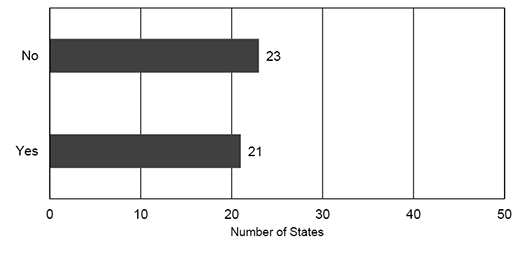

Exit Decision-makers for ELs. States were asked to indicate whether the state required that specific individuals be involved in the decision to exit an EL from EL services. Forty-four states responded to this question (two states skipped it). Of the 44 states, more than 50% indicated that the state did not require that specific individuals be involved in the decision (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. State Requires Specific Individuals to be Involved in Exit Decisions for ELs (n=44)

Of the 21 states that required specific individuals to be involved, responses varied as to the individuals who needed to be involved. Six states indicated that a team must make the decision; the team members identified included diverse individual roles such as an EL teacher, classroom teacher, EL coordinator, and building administrator. The states that did not mention a team generally mentioned more than one individual as being able to decide, including the ELP administrator, the EL teacher, and a counselor. Among the open-ended responses were the following:

Respondents were also asked to identify the specific individuals typically included in the decision process in districts. Most states indicated that information on who actually was involved in exit decisions in districts was not available. Those states that did indicate some knowledge of who the individuals were reported that there was variation across the districts. Open-ended responses reflected this variability:

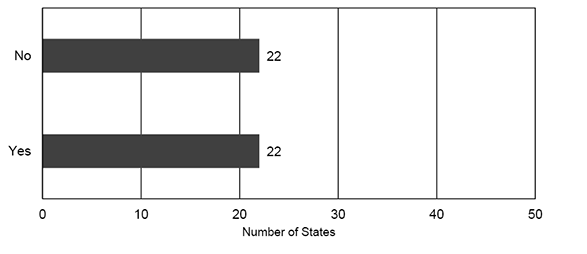

Exit Decision-makers for ELs with Disabilities. Respondents were asked to indicate whether the state required specific individuals to be involved in the exit decision for ELs with disabilities. Half of the 44 respondents to this question indicated that the state did not require specific individuals to be involved in the decision (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. State Requires Specific Individuals to be Involved in Exit Decisions for ELs with Disabilities (n=44)

Of the 22 states that reported that specific individuals were required to be involved in the exit decision for ELs with disabilities, most indicated that the same individuals who made the decision for ELs without disabilities made the decision for ELs with disabilities. Seven states indicated that the IEP team or a member of the IEP team must be involved in the decision. A few states specifically mentioned that parents could refuse EL services. Among the comments made in response to the question about which individuals must be involved in the decision were the following:

Respondents were also asked to identify the individuals districts included in the exit decision process for ELs with disabilities. Twenty states responded to this open-ended question. Seven states indicated that the information on who actually participated was not available. Other states replied that districts followed state recommendations. Examples of their comments were the following:

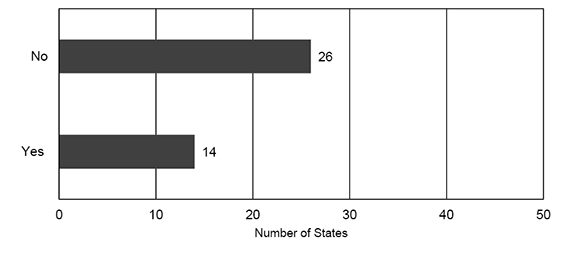

States were also asked whether exiting from EL services was addressed in the IEP process. Forty states responded to this question, with nearly two-thirds of them indicating that exiting of ELs with disabilities was not addressed in the IEP process (see Figure 4), although many of them indicated that they marked "no" because they were not sure or did not know.

Figure 4. States in Which Exiting from EL Services is Addressed in the IEP Process (n=40)

A number of states added comments in response to this question. Several indicated that they "hoped" so, or that the decision should be part of the IEP process. Examples of specific comments to this question include the following:

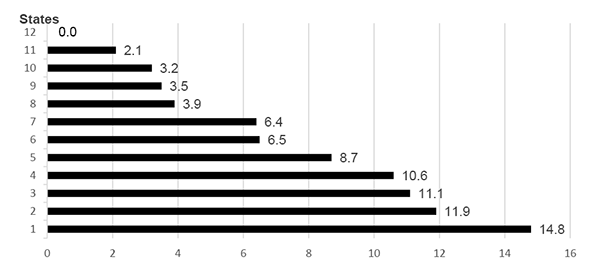

Exited Numbers and Tracking. When asked how many ELs with disabilities were exited from EL services during 2013-14, only 37 states responded. Most states indicated that the number was not available, or that the respondent did not have access to the number but that another person or department might have the number. Ten states provided a number, which ranged from 0 to 1,406 (average = 232). When the percentage of ELs with disabilities who exited was calculated, based on the number of ELs with disabilities reported in IDEA Part B Child Count and Educational Environments data for 2012, it ranged from 0.0% to 14.8%. Additionally one state did not provide the number of students exited but merely indicated that 10.6% of students exited. As shown in Figure 5, in one state fewer than 1% of ELs with disabilities exited in 2013-14. Four states exited between 1.0% and 5.0% of ELs with disabilities, three states exited between 5.1% and 10.0%, and four states exited between 10.1% and 15.0%.

Figure 5. Percentage of ELs with Disabilities Exited from Services, 2013-14 (N=12)

Note: Percentages were calculated using as the numerator ELs with disabilities exit data for 2013-14 reported by states in the survey. The denominator was the number of ELs with disabilities for 2012-13, which was based on IDEA Part B Child Count and Educational Environments data for 2012 (See Liu et al., 2016).

Among the comments that were made by states were the following:

States were also asked whether the ELs with disabilities who were exited from services could be tracked after their exit from EL services, disaggregated from other exited ELs. The majority of the 39 responding states (62%) indicated that they could track ELs with disabilities, separate from ELs who have been exited (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. States Able to Track ELs with Disabilities Who Were Exited from Services (n=39)

Although the majority of responding states indicated that the state could disaggregate ELs with disabilities exit data from the exit data for other ELs, their comments suggested that getting the data was possible, but that it would be difficult to actually generate this information, most often because getting the data would depend on another unit in the state department of education. Examples of comments that were made included:

Additional Information. States were provided the opportunity to add information about anything else related to ELs with disabilities. With this opportunity, a number of states indicated that they were in the process of developing materials that they believed would be helpful with the exit process for ELs with disabilities. Respondents in other states commented on the difficulty of exiting ELs with significant cognitive disabilities from EL services, specifically referring to what respondents saw as unrealistic criteria that existed for this population to exit from services. Representative comments here included:

Top of Page | Table of Contents

This survey provided a baseline of where states were in 2015-16 in terms of making exit decisions for ELs with disabilities. The high response rate (90% of the states and DC) gives a strong indication of the importance that states give to this issue. Some states have clear exit criteria for ELs with disabilities for districts to use, though in many of those cases, they are the same for ELs and ELs with disabilities. Many states do not have a specific exit process or criteria for ELs with disabilities, allowing the districts to establish their own criteria. In fact, most states do not even know how many ELs with disabilities exit EL services and in most of the states that do know, relatively few students exit.

It is difficult to compare these exit rates for ELs with disabilities to the overall exit rates for all ELs because the data are not publicly available. Estimates derived from data in states' Consolidated State Performance Reports suggest that the same 12 states included in Figure 5 have overall exit rates that range from 1% to 18%, but that the lowest rate state for ELs with disabilities is the seventh lowest rate state for ELs overall and the highest rate state for ELs overall is the sixth lowest rate state for ELs with disabilities. In some states the two rates are very close to each other but in other states they are quite different.

Even though we obtained a high response rate to the survey, a limitation of this study is that some of the largest states, as well as some other states with the highest percentages of ELs, did not complete the survey. Based on conversations with survey recipients in some of these states, we believe that political issues, compliance concerns, and other related factors may have affected their decision about whether to participate. These states may have processes and procedures in place that this survey failed to pick up.

The survey findings suggest that many states may benefit from developing (or refining) exit criteria for ELs with disabilities. Some considerations include:

Consider using multiple measures of exit readiness. The use of data from a single measure may be problematic for some ELs with disabilities (Thurlow, Christensen, & Shyyan, 2016). For example, a student who is deaf or hard of hearing may not be able to complete items in the speaking domain on an ELP assessment in the same way as other students. Similarly, students who are blind and use braille to access text may not read in the same way as other students.

Consider using a team approach to decision making that includes both IEP and EL team members. ELs with disabilities have needs and characteristics that make it difficult for any one individual to have sufficient knowledge and expertise to make sound exit decisions. Best practice is to use a team approach. IEP team members joined by an EL team of educators who know the student well have the collective knowledge and skills to make sound exit decisions. In many cases, the IEP team would include one or more members with expertise in language acquisition that could play a key role in the decision-making process.

States should consider how their current and proposed practices for exiting ELs with disabilities align with the requirements under ESSA, and review any recently-issued regulations and guidance that pertain to this population. For example, the Department of Education's September 2016 Non-Regulatory Guidance: English Learners and Title III of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) (U.S. Department of Education, 2016) includes a section specific to English learners with disabilities.

Top of Page | Table of Contents

Abedi, J. (2009). English language learners with disabilities: Classification, assessment, and accommodation issues. Journal of Applied Testing and Technology, 10(2).

Linan-Thompson, S., Vaughn, S., Prater, K., & Cirino, P. T. (2006). The response to intervention of English language learners at risk for reading problems. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 39, 390-398.

Linquanti, R., & Cook, H. G. (2013). Toward a common definition of English learner: Guidance for states and state assessment consortia in defining and addressing policy and technical issues and options. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Linquanti, R., & Cook, H. G. (2015). Re-examining reclassification: Guidance from a national working session on policies and practices for exiting students from English learner status. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

Liu, K. K., Goldstone, L. S., Thurlow, M. L., Ward, J. M., Hatten, J., & Christensen, L. L. (2013). Voices from the field: Making state assessment decisions for English language learners with disabilities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Improving the Validity of Assessment Results for English Language Learners with Disabilities (IVARED).

Liu, K. K., Albus, D. A., Lazarus, S. S., & Thurlow, M. L. (2016). State and national demographic information for English learners (ELs) and ELs with disabilities, 2012-13 (Data Analytics #4). Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Liu, K., & Barrera, M. (2013). Providing leadership to meet the needs of English language learners with disabilities. Journal of Special Education Administration, 26, 31-42.

Liu, K. K., Ward, J. M., Thurlow, M. L., & Christensen, L. L. (2015). Large-scale assessment and English language learners with disabilities. Educational Policy, Advance online publication. doi: 0.1177/0895904815613443

Office of Special Education Programs. (2011, January). Memorandum on RTI. Available at http://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/idea/memosdcltrs/osep11-07rtimemo.pdf

Rinaldi, C., & Samson, J. (2008). English language learners and response to intervention: Referral Considerations. Teaching Exceptional Children. 40(5), 6-14.

Thurlow, M. L., Christensen, L. L, & Shyyan, V. V. (2016). White paper on English language learners with significant cognitive disabilities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes, English Language Proficiency Assessment for the 21st Century.

U.S. Department of Education. (2014, July). Questions and answers regarding the inclusion of English learners with disabilities in English language proficiency assessments and Title III annual measurable objectives. Washington, DC: Author. Available at https://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/idea/memosdcltrs/q-and-a-on-elp-swd.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education (2015, July). Addendum to Questions and Answers Regarding Inclusion of English Learners with Disabilities in English Language Proficiency Assessments and Title III Annual Measurable Achievement Objectives issued July 18, 2014 (2014 Qs and As) Washington, DC: Author. Available at https://www2.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/idea/memosdcltrs/addendum-q-and-a-on-elp-swd.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education. (2016, September). Non-regulatory guidance: English learners and Title III of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Washington, DC: Author. Available at http://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/essa/essatitleiiiguidenglishlearners92016.pdf.

Zehler, A., Fleischman, H., Hopstock, P., Stephenson, T., Pendzick, M., & Sapru, S. (2003). Descriptive study of services to LEP students and LEP students with disabilities (Vol. 4). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement, and Academic Achievement for Limited English Proficient Students.

Top of Page | Table of Contents

(Q1 was respondent contact information)

2. Does your state have specific criteria for districts to use when judging whether an English learner (EL) with a disability has achieved English proficiency and is ready to be EXITED from EL services? (YES-NO RESPONSE)

3. What are the criteria that your state uses? (If the criteria specifically address ELs with disabilities who have certain characteristics please include that information--e.g., students with significant cognitive disabilities, students who are deaf/hard-of-hearing, etc.). How are these criteria different from those for ELs without disabilities? (OPEN ENDED RESPONSE)

4. Do you know what criteria are used in the districts in your state? If so, please provide some common examples? (YES-NO RESPONSE, with comments)

5. Does your state require specific individuals to be involved in the decision to EXIT an EL from EL services? (YES-NO RESPONSE)

6. Which specific individuals are involved (OPEN ENDED RESPONSE)

7. Do you know which specific individuals typically are included in that decision process in the districts in your state? Please list those individuals. (OPEN ENDED RESPONSE)

8. Does your state require specific individuals to be involved in the decision to EXIT an EL with a disability from EL services (YES-NO RESPONSE)

9. Which specific individuals must be involved in the decision? (OPEN ENDED RESPONSE)

10. Do you know which individuals districts typically include in the decision process? Please list those individuals. (OPEN ENDED RESPONSE)

11. Is EXITING from EL services addressed in the IEP process? (YES-NO RESPONSE, with comments)

12. How many ELs with disabilities were EXITED from EL services during 2013-14? (OPEN ENDED RESPONSE)

13. Can those ELs with disabilities who are tracked after they EXIT services be disaggregated from other exited ELs who are tracked? (YES-NO RESPONSE, with comments)

14. Is there anything else you would like us to know about ELs with disabilities in your state? (OPEN ENDED RESPONSE)