Christopher M. Rogers, Sheryl S. Lazarus, and Martha L. Thurlow

May 2016

All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Rogers, C. M., Lazarus, S. S., & Thurlow, M. L. (2016). A summary of the research on the effects of test accommodations: 2013-2014 (NCEO Report 402). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

The use of accommodations in instruction and assessments continues to be of great importance for students with disabilities. This importance is reflected in an emphasis on research to investigate the effects of accommodations. Key issues under investigation include how accommodations affect test scores, how educators and students perceive accommodations, and how accommodations are selected and implemented.

The purpose of this report is to provide an update on the state of the research on testing accommodations as well as to identify promising future areas of research. Previous reports by the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) have covered research published since 1999. We summarize the research to review current research trends and enhance understanding of the implications of accommodations use in the development of future policy directions, implementation of current and new accommodations, and valid and reliable interpretations when accommodations are used in testing situations. In 2013 and 2014, 53 published research studies on the topic of testing accommodations were found. Among the main points of the 2013-14 research are:

Purpose: More than 40 percent of the research was to evaluate the comparability of test scores when assessments were administered with and without accommodations. The next most common purpose was to report on perceptions and preferences about accommodations use. The majority of studies addressed multiple purposes.

Research design: About 72% of the studies reported primary data collection on the part of the researchers, rather than drawing on existing (extant) data sets. Over two-fifths of the studies involved quasi-experimental designs. Researchers also drew on a variety of other quantitative and qualitative methodologies, including survey methodologies and meta-analyses.

Types of assessments, content areas: A wide variety of instrument types were used in these studies. About half of the studies used non-academic protocols or surveys developed by the study authors. Other studies used academic content items drawn from specified sources outside of the researchers' work, including state criterion-referenced test data, norm-referenced measures, or multiple types of data. Mathematics and reading were the most common content areas included in the 2013-2014 research. Other content areas included science and writing. About 17 percent of all studies addressed more than one content area in the assessments used.

Participants: Participants were most frequently students, spanning a range of grade levels from K-12 to postsecondary students, although several studies included educators as participants. Studies varied in the number of participants; some studies included fewer than 10 participants, whereas other studies involved hundreds of thousands of participants.

Disability categories: Learning disabilities was the most common disability category exhibited by participants in the research, accounting for over half of the studies. Attention problems, emotional behavioral disability, and autism were the next most commonly studied. Low-incidence disabilities were included in more than one-third of the studies.

Accommodations: Presentation accommodations were the most frequently studied category, with oral delivery (read-aloud) accommodations being the most studied within this category (and across categories). Another commonly studied accommodation was extended time.

Findings: Empirical studies investigating performance effects of the extended time accommodation showed a positive impact on assessment scores for students with disabilities. There were not conclusive findings for the oral delivery accommodation; two studies found a differential boost for students with disabilities when compared to students without, three found performance improvements for both students with and without disabilities, and one found no significant benefits. The two studies that addressed calculators both showed positive, although nuanced, support for students with disabilities' performance. The two studies that addressed setting accommodations did not find significant evidence that there was a benefit of separate, low-distraction settings for students with disabilities. Two-thirds of the studies that looked at student perceptions found that most or all participants viewed accommodations as helping them perform better on assessments. About half of the studies of educators' perceptions of test enhancements (accommodations and modifications) found that educators believed that they were beneficial to student test-takers' performance and to students' emotional state and self-esteem.

Limitations: Several limitations of the studies were identified. The most frequently listed limitation was related to small sample size, and other sampling issues. The next most frequently mentioned limitation was methodological limitations and issues related to the lack of authenticity of the testing circumstances.

Directions for future research: A number of promising suggestions were noted, particularly the need for more rigorous studies that used stronger sampling methods. Many studies also noted a need for future studies that had an improved interface between accommodations and naturalistic testing conditions (test/test context).

All students, including students with disabilities, are required by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004 and Title I of the 2015 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) to participate in assessments used for accountability. Some students need accommodations to meaningfully access assessments. States and assessment consortia look to accommodations research when making policy decisions about accommodations.

To synthesize accommodations research efforts completed across the years, the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) has published a series of reports on accommodations research. The time periods included 1999-2001 (Thompson, Blount, & Thurlow, 2002), 2002-2004 (Johnstone, Altman, Thurlow, & Thompson, 2006), 2005-2006 (Zenisky & Sireci, 2007), 2007-2008 (Cormier, Altman, Shyyan, & Thurlow, 2010), 2009-2010 (Rogers, Christian, & Thurlow, 2012), and 2011-2012 (Rogers, Lazarus, & Thurlow, 2014). This report covers the time period 2013-2014.

The purpose of this report is to present a synthesis of the research on test accommodations published in 2013 and 2014. The literature described here encompasses empirical studies of score comparability and validity studies as well as investigations into accommodations use, implementation practices, and perceptions of their effectiveness. As a whole, the current research body offers a broad view and a deep examination of issues pertaining to assessment accommodations. Reporting the findings of current research studies was a primary goal of this analysis; a secondary goal was to identify areas requiring continued investigation in the future.

Similar to the process used in past accommodations research syntheses (Cormier et al., 2010; Johnstone et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2012; Rogers et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2002; Zenisky & Sireci, 2007), a number of sources were accessed to complete the review of the accommodations research published in 2013 and 2014. Specifically, five research databases were consulted: Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), PsycINFO, Academic Search Premier, Digital Dissertations, and Educational Abstracts. To help confirm the thoroughness of our searches, we used the search engine Google Scholar to search for additional research. In addition, a hand-search of 47 journals was completed, in efforts to ensure that no qualifying study was missed. A list of hand-searched journals is available on the NCEO website (https://nceo.info/Resources/bibliographies/accommodations/bibliography).

Online archives of several organizations also were searched for relevant publications. These organizations included Behavioral Research and Teaching (BRT) at the University of Oregon (http://brt.uoregon.edu), the College Board Research Library http://research.collegeboard.org), the National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST; http://www.cse.ucla.edu), and the Wisconsin Center for Educational Research (WCER; http://testacc.wceruw.org/).

The initial search was completed in December, 2014. A second search was completed in May, 2015, to ensure that all articles published in 2013 and 2014 were found and included in this review. Within each of these research databases and publications archives, we used a sequence of search terms. Terms searched for this review were:

Many of these search terms were used as delimiters when searches yielded large pools of documents found to be irrelevant to the searches.

The research documents from these searches were then considered for inclusion in this review using several criteria. First, this analysis included only research published or defended (in doctoral dissertations) in 2013 and 2014. Second, the scope of the research was limited to investigations of accommodations for regular assessment; hence, articles specific to alternate assessments, accommodations for instruction or learning, and universal design in general were not part of this review. Third, research involving English learners (ELs) was included only if the target population was ELs with disabilities. Fourth, presentations from professional conferences were not searched or included in this review, based on the researchers' criteria to include only research that would be accessible to readers and that had gone through the level of peer review typically required for publication in professional journals or through a doctoral committee review. (This criterion was implemented for the first time during the 2007-2008 review.) Finally, to be included in the online bibliography and summarized in this report, studies needed to involve: (a) experimental manipulation of an accommodation, (b) investigation of the comparability of test scores across accommodated and non-accommodated conditions, or (c) examination of survey results or interview data sets about students' or teachers' knowledge or perceptions of accommodations.

To reflect the wide range of accommodations research that was conducted in 2013 and 2014, the studies are summarized and compared in the following ways: (a) publication type, (b) purposes of research, (c) research type and data collection source, (d) assessment or data collection focus, (e) characteristics of the independent and dependent variables under study, (f) comparability of findings between studies in similar domains, and (g) limitations and directions of future research.

Top of Page | Table of Contents

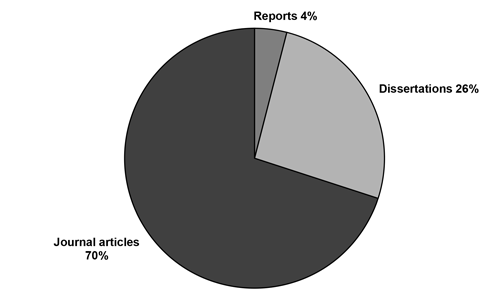

A total of 53 studies was published between January 2013 and December 2014. As shown in Figure 1, of the 53 studies, 37 were journal articles, 14 were dissertations, and 2 were published professional reports released by research organizations or entities (e.g., ETS).

Figure 1. Percentage of Accommodations Studies by Publication Type

The total number of studies published on accommodations in 2013-2014 (N=53) increased slightly from accommodations research published in 2011-2012 (n=49). The number of journal articles was nearly the same (n=37 in 2013-2014; n=39 in 2011-2012), but the number of dissertations published on accommodations doubled (n=14 in 2013-2014; n=7 in 2011-2012). The report on accommodations research in 2011-2012 (Rogers et al., 2014) included 39 articles from 23 journals; the 37 articles described in the current report were published in 27 journals. (Appendix B, Table B-1, presents individual study information about publication type.)

A number of purposes were identified in the accommodations research published in 2013 and 2014. Table 1 shows the primary focus of each of these 53 studies. Eight studies each listed a single purpose (see Appendix A, Table A-1). The majority of studies reviewed sought to accomplish multiple purposes. In those cases, we identified the "primary purpose" based on the title of the work or the first-mentioned purpose in the text.

Table 1. Primary Purpose of Reviewed Research

| Purpose | Number of Studies | Percent of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Compare scores | 23 | 43% |

| only students with disabilities (6 studies) | ||

| only students without disabilities (2 studies) | ||

| both students with and without disabilities (16 studies) | ||

| Study/compare perceptions and preferences about use | 12 | 23% |

| Report on implementation practices and accommodations use | 8 | 15% |

| Summarize research on test accommodations | 8 | 15% |

| Develop test | 1 | 2% |

| Investigate test validity | 1 | 2% |

| Compare test items | 0 | 0% |

| Discuss issues | 0 | 0% |

| Identify predictors of the need for test accommodations | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 53 | 100% |

The most common primary purpose for research published during 2013-2014 was to report on the effect of accommodations on test scores (43%) by comparing scores of students who received accommodations to those who did not (see Appendix A). The next most common primary purpose was studying perceptions of accommodations, including preferences between or among a small number of accommodations (23%). The third most common purposes were reporting on implementation practices and accommodations use (15%), and also summarizing research on test accommodations (15%).

Reviews of research on accommodations included explorations of the research: (a) on a specific accommodation's effect for assessment participants (Nees & Berry, 2013), (b) on various accommodations for students with a single disability category (Cawthon & Leppo, 2013), and (c) about a specific accommodation for students with a single disability category (Lewandowski, Cohen, & Lovett, 2013). A specific type of literature review--meta-analysis--as a primary purpose, was exemplified by Li (2014). In this analysis, test development and investigating test validity each were represented by a single study. Test development was investigated by Ketterlin-Geller, Crawford, and Huscroft-D'Angelo (2014) and test validity was examined in Cawthon, Leppo, Carr, and Kopriva (2013).

Table 2 shows the multiple purposes of many studies. Several studies with more than one purpose had two purposes--for example, some studies (Abedi & Ewers, 2013; Cawthon & Leppo, 2013; Li, 2014; Lovett, 2014; Lovett & Leja, 2013; Nees & Berry, 2013) both reviewed the literature and discussed pressing accommodations issues. Other studies (Berger & Lewandowski, 2013; Higgins & Katz, 2013; Meyer & Bouck, 2014) included analyses of score comparisons between students with disabilities and students without disabilities when using accommodations, while also analyzing students' perceptions based on responses from surveys or interviews.

Table 2. All Purposes of Reviewed Research

| Purpose | Number of Studies | Percent of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Compare scores | 25 | 46% |

| only students with disabilities (11% of studies) | ||

| only students without disabilities (4% of studies) | ||

| both students with and without disabilities (31% of studies) | ||

| Summarize research on test accommodations | 22 | 44% |

| Study/compare perceptions and preferences about use | 22 | 44% |

| Discuss issues | 17 | 32% |

| Report on implementation practices and accommodations use | 14 | 26% |

| Investigate test validity | 8 | 15% |

| Compare test items | 2 | 4% |

| Identify predictors of the need for test accommodations | 1 | 2% |

| Develop test | 1 | 2% |

The total of these percentages is >100% due to the multiple purposes identified in most (45) of the studies; 34 studies had 2 identified purposes, 9 studies had 3 identified purposes, and 2 studies had 4 identified purposes.

When all purposes (i.e., primary, secondary) are included, the most common single purpose of the 2013-2014 studies was demonstrating the effect of accommodations on test scores (46% of studies). Study approaches compared test scores of students with disabilities and students without disabilities when using accommodations, or compared test scores of students with disabilities when using and not using accommodations, or compared test scores of students without disabilities when using and not using accommodations. Of these three approaches to studying the effects of accommodations on performance, comparing scores of students with disabilities and students without disabilities was the most frequent--fully two-thirds (n=17) of the relevant 25 studies (see Appendix A, Table A-1). The second most frequent research purpose was summarizing research on test accommodations, typically reviewing research on the effects of accommodations in various assessment contexts. The frequency of this purpose is due to the number of dissertations; every dissertation had a substantive literature review. The third most common purpose was studying perceptions of accommodations.

Another purpose we identified in almost one-third of the studies was discussing issues. Although not reported as a primary purpose for any of the studies, discussing issues was often noted as a second purpose. For example, Freeman (2013) discussed issues of transitioning some students with disabilities from taking the alternate assessment based on modified achievement standards (AA-MAS) to taking the state's general assessment. The purpose of reporting on implementation practices or accommodations use was part of over one-fourth of the studies. For instance, Barnhill (2014) reported on postsecondary faculty members' current accommodations practices with students with Asperger Syndrome, and Schreuer and Sachs (2014) reported on accommodations commonly used by postsecondary students with disabilities in general.

The purpose of investigating test validity when students used accommodations was explored in some studies (n=8). Typically, studies having this purpose sought to analyze whether use of accommodations fundamentally changed the construct being assessed. For example, Lin and Lin (2013) examined the construct validity of a mathematics assessment when selected setting accommodations were used, while Stone, Cook, and Laitusis (2013) examined the construct validity of oral delivery of an assessment of reading comprehension.

This analysis of accommodations research found that some of the least common purposes were comparing test items, predicting accommodations need, and developing tests. Huggins and Elbaum (2013) performed a score equity assessment, analyzing item-level responses for equating invariance. The purposes of identifying predictors of the need for test accommodations, and developing a test, were both exemplified by Ketterlin-Geller, Crawford, and Huscroft-D'Angelo (2014), who developed an accommodations assignment screening test and analyzed factors disrupting accurate mathematics performance scores and indicating students' needs for specific accommodations.

Over 40% of the 2013-2014 accommodations research used a quasi-experimental research design. As displayed in Table 3, the researchers themselves gathered the data (i.e., primary source data) in over three times as many quasi-experimental studies (n=17) compared to studies with secondary data sources using extant or archival data (n=5). The number of quasi-experimental research studies decreased in 2014 compared to 2013. Likewise, descriptive quantitative analyses and descriptive qualitative analyses also decreased from 2013 to 2014, consistent with an overall decrease in studies from 2013 (n=30) to 2014 (n=23). In 2013 and 2014 researchers also conducted few studies using correlational, experimental, and meta-analytic designs. No studies used longitudinal designs. The relative frequency of the selected research designs is consistent with previous biennial periods examined in past reports, though in the past a few studies typically had longitudinal designs.

We also observed a similarity in data collection sources between the current reporting period and the previous reporting period. In 2013-2014, primary data were used in 38 studies (72%) and secondary data were used in 15 studies (28%). This difference between data sources is even larger than the previous report (Rogers et al., 2014) in which about twice as many studies used primary data in comparison to secondary data sources. (Appendix B, Table B-1, presents research designs and data collection sources for individual studies.)

Table 3. Research Design and Data Collection Source by Year

| Research Design | Data Collection Source | Total Sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | ||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2013 | 2014 | ||

| Quasi-experimental | 10 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 22 |

| Descriptive quantitative | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Descriptive qualitative | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 13 |

| Correlation/prediction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Experimental | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Longitudinal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meta-analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Year Totals | 22 | 16 | 8 | 7 | 53 |

| Source Totals Across Years | 38 | 15 | 53 | ||

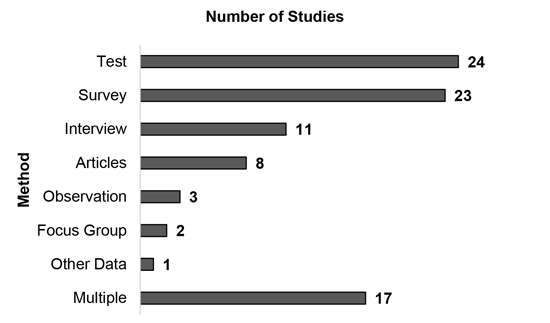

The research included in this analysis used the methods shown in Figure 2 to collect study data. Nearly half of the research (n=24, 46%) used performance data acquired through academic content testing. In some of the cases, tests were administered as part of the study; in other cases, extant data sources were used. Surveys were also another common data source, while interviews, observations, and focus groups were less commonly used methods of collecting data. Another less frequently used method was "articles." This term refers to eight studies that reviewed research literature, including two studies that employed formal meta-analysis techniques. Only one study (Schreuer & Sachs, 2014) collected other data (i.e., student course grades) as one of its measures. About one-third of the studies reported using more than one method or tool to gather data. (See Appendix B, Table B-1, for additional details about each study's data collection methods.)

Figure 2. Data Collection Methods Used in 2013-2014 Research

Note. Of the 53 studies reviewed for this report, 15 reported using two data collection methods, and 2 reported using three data collection methods.

Nearly all of the 2013-2014 studies used some type of data collection instrument; only five studies did not employ any instruments (e.g., literature reviews). Table 4 shows the types of data collection instruments used. Surveys presented items of an attitudinal or self-report nature. Tests were course- or classroom-based. Assessments were statewide or large-scale in scope. Protocols refer to sets of questions, usually presented in an interview or focus group format. Measures referred to norm-referenced academic or cognitive instruments. All of these instruments were placed into five categories: non-test protocols or surveys developed by study authors, surveys or academic tests developed by education professionals or drawn by researchers from other sources, norm-referenced academic achievement measures, norm-referenced cognitive ability measures, and state criterion-referenced academic assessments. Non-test protocols developed by the author or authors of the studies--the most commonly-used instrument (in 49% of studies)--included performance tasks, questionnaires or surveys, and interview and focus-group protocols, among others. Surveys or academic tests developed by education professionals or researchers used sources outside of current studies, and were exemplified by perception surveys such as the State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES; Heatherton & Polivy, 1991, as in Wadley & Liljequist, 2013), or by English language arts test items based on the reading framework for the 2009 National Assessment of Educational Progress (National Assessment Governing Board, 2008, as cited in Stone et al., 2013).

State criterion-referenced assessments included those of Georgia, Missouri, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Ontario, Canada, and released items from state assessments in Arizona, Massachusetts, Ohio, and Virginia, as well as assessments from states that remained unidentified in the research. Fifteen norm-referenced academic achievement measures were used in one or more studies, including the Graduate Record Examination (GRE), the Nelson-Denny Reading Test (NDRT), and the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-Second Edition (WIAT-II). Norm-referenced cognitive ability measures were used in three studies, and included the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities III (WJIII), among others. A substantial minority--19 studies in all--used instrumentation of more than one kind. We present a complete listing of the instruments used in each of the studies in Table C-1 in Appendix C, including the related studies that served as sources for these instruments, when available.

Table 4. Data Collection Instrument Types

| Instrument Type | Number of Studies | Percent of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Non-academic protocols or surveys developed by study author/s | 26 | 49% |

| Surveys or academic tests developed by professionals or researchers using sources outside of current study | 13 | 25% |

| Norm-referenced academic achievement measures | 15 | 28% |

| State criterion-referenced assessments | 15 | 28% |

| Norm-referenced cognitive ability measures | 3 | 6% |

| Othera | 2 | 4% |

| Noneb | 5 | 9% |

| Multiple (types) | 19 | 36% |

a Other: 1 study used the Learning Achievement Test in geometry, developed by study researchers based on instructional content (Lee & Chen, 2014), 1 study used an extant data set of interview responses (Newman & Madaus, 2014).

b None: 5 studies were literature reviews of studies employing various data collection approaches and/or instruments (Abedi & Ewers, 2013; Barnhill, 2014; Lovett, 2014; Lovett & Leja, 2013; Nees & Berry, 2013).

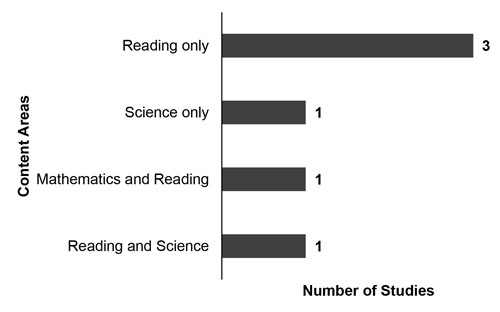

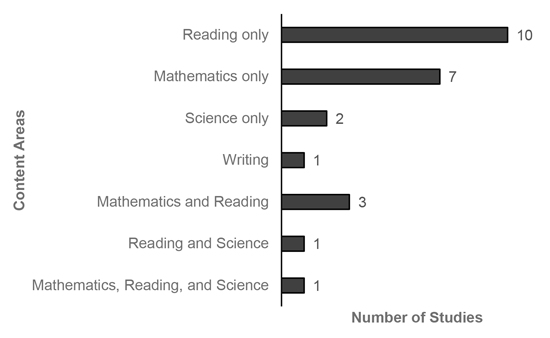

A number of studies published during 2013-2014 focused on accommodations used in specific academic content areas. As shown in Table 5, math and reading were the two most commonly studied content areas. Table 5 also provides a comparison to content area frequency found in NCEO's previous analyses of accommodations research (Rogers et al., 2012, 2014). Across the years, reading and mathematics have been the most common content areas for this research; however, the number and the proportion of studies addressing math and reading assessments, and nearly all other content assessments (except science), have decreased. This decrease is related to a general decrease in the number of studies that used assessment data in 2013-2014. There has been little change across years in the percentage of studies addressing science. The number of studies on writing, social studies, and psychology has remained fairly consistent since 2005. There have been no accommodations research studies in the areas of Civics/U.S. History since 2005-2006, so we did not include this content area in the current report. All studies with assessment data published in 2013-2014 reported their associated content areas. This marks a change from the previous report, in which two studies did not specify the content areas of the assessments and their accommodations. (See Appendix C, Table C-2, for additional details about the content areas.)

Table 5. Academic Content Area Assessed Across Three Reports

| Content Area Assessed | 2009-2010a | 2011-2012b | 2013-2014c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematics | 20 (42%) | 22 (45%) | 14 (26%) |

| Reading | 16 (33%) | 19 (39%) | 16 (30%) |

| Writing | 3 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 2 (4%) |

| Other language artsd | 4 (8%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) |

| Science | 7 (15%) | 4 (8%) | 5 (9%) |

| Social studies | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Psychology | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not specific | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Multiple content | 13 (27%) | 16 (33%) | 9 (17%) |

a Studies in 2009-2010 included examinations of more than one content area ranged in number of areas assessed from 2 to 5.

b Studies in 2011-2012 included examinations of more than one content area ranged in number of areas assessed from 2 to 4.

c Studies in 2013-2014 included examinations of more than one content area ranged in number of areas assessed from 2 to 3.

d Detailed descriptions of what constituted "Other Language Arts" for each of the three states from 2013-2014 can be found in Appendix C, Table C-2.

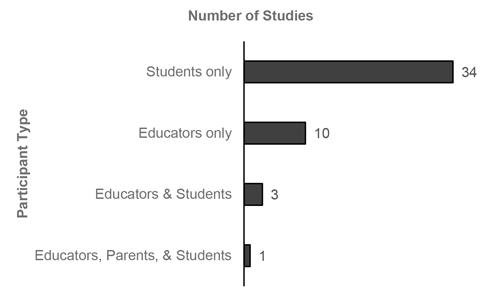

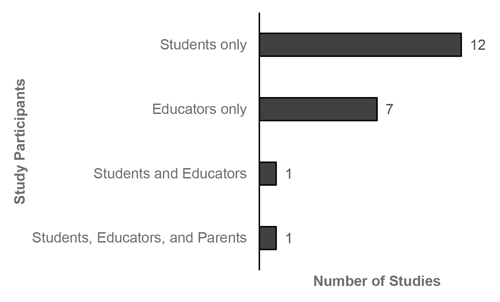

The studies in this analysis of accommodations research included participants in several roles (see Figure 3 and Appendix D, Table D-1). In 2013-2014, a majority of the studies included only students--35 of the 53 studies (66%). The next largest participant group studied (19% of studies) was "educators only." This refers to studies that described or analyzed the educator perspective on accommodations. Both educators and students were included in three studies. The other participant category in 2013-2014 was educators, parents, and students. Only one study (Torres, 2014) was in this group. Five studies did not draw data from research participants.

Table 6 details the composition and size of the participant groups in the research studies published during 2013 and 2014. This information is displayed in more detail by study in Appendix D, Table D-1. The size of the participant groups varied from 3 (Meyer & Bouck, 2014) to 191,906 (Huggins & Elbaum, 2013). The number of participants was fairly evenly spread across the continuum of percentages represented by those numbers, according to data reported in Appendix Table D-1. In addition, the number of studies in which there were more participants without disabilities (n=29) was higher than the number of studies in which there were more students with disabilities (n=20). When the studies with only educator participants (n=10) were taken into account, the composition of the participant groups was fairly even across studies with more students with disabilities and those with more students without disabilities.

Figure 3. Types of Research Participants (n=48)

Table 6. Participant Sample Sizes and Ratio of Individuals with Disabilities

| Number of Research Participants by Study | Number of Studies by Proportion of Sample Comprising Individuals with Disabilities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-24% | 25-49% | 50-74% | 75-100% | Unavailable | Total | |

| 1-9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| 10-24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| 25-49 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 50-99 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 100-149 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| 150-199 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 200-299 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 300-499 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 500-999 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 1000 or more | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Unavailable | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 21 | 8 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 49 |

Similar to the previous report on accommodations research (Rogers et al., 2014), research during 2013-2014 involved kindergarten through postsecondary participants (see Table 7). See Appendix D for more detail. Postsecondary refers to both university students and other participants in postsecondary settings. For example, Young (2013) investigated the accommodations knowledge and practices of academic advisors in the college environment. The largest number of studies published in 2013 and 2014 focused on elementary students (n=16; 30%), followed by postsecondary students (n=14; 26%) and middle school students (n=12; 23%). The lowest proportion of studies was at the high school level (11% of studies; n=6). Only 8 studies included students in more than one grade-level cluster.

Table 7. School Level of Research Participants

| Education Level of Participants in Studies | Number of Studies | Percent of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Elementary school (K-5) | 16 | 30% |

| Middle school (6-8) | 12 | 23% |

| High school (9-12) | 6 | 15% |

| Postsecondary | 14 | 26% |

| Multiple grade-level clusters | 8 | 15% |

| No age | 10 | 19% |

| Not applicable | 5 | 9% |

The accommodations research in 2013-2014 addressed a broad range of disability categories (see Appendix D for details). As shown in Table 8, only five studies did not specify disability categories of student participants and 10 studies did not include students in the sample. Of the remaining 37 studies, the most commonly studied student disability category was learning disabilities (n=31); five of these studies had only participants with learning disabilities, and 10 more compared students with learning disabilities to students without disabilities.

Table 8. Disabilities Reported for Research Participants

| Disabilities of Research Participants | Number of Studiesa | Percent of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Learning disabilities | 31 | 58% |

| Attention problem | 13 | 25% |

| Emotional behavioral disability | 13 | 25% |

| Autism | 12 | 23% |

| Multiple disabilitiesb | 12 | 23% |

| Physical disabilityc | 11 | 21% |

| Deafness/Hearing impairment | 10 | 19% |

| Blindness/Visual impairment | 9 | 17% |

| Intellectual disabilities | 8 | 15% |

| Speech/Language | 7 | 13% |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 | 2% |

| No disability | 22 | 42% |

| Not specifiedd | 5 | 9% |

| Not applicablee | 10 | 19% |

aStudies sometimes included student participant groups from more than one disability category.

bMultiple disabilities = individual students who were each specifically categorized as having more than one disability

cPhysical disability = mobility impairments and/or impairment with arm use.

dNot specified = those studies (4) or reviews of studies (1) that did not report about or provide detail as to the participants' disabilities.

eNot applicable = those documents that had only non-students as participants.

About one-third of the remaining 37 studies included students with attentional difficulties (n=13), students with emotional behavioral disabilities (n=12), students with autism-related disabilities (n=12), and students with "multiple disabilities" (n=12). Almost one-fourth of the relevant studies included students with physical disabilities (n=11), or students with deafness or hearing impairments (n=10). About one-fourth included students with blindness or visual disabilities (n=9), or students with intellectual disabilities (n=8). About one-fifth of the studies included students with speech/language impairments (n=7). One study (Freeman, 2013) specifically mentioned including students with traumatic brain injuries. Over one-half of the relevant studies included students without disabilities as comparison groups. Except for studies that addressed accommodations and students with learning disabilities, very few studies examined accommodations for only participants with one specific category of disability.

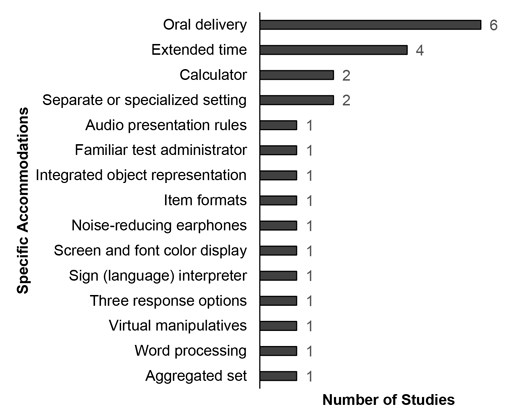

The number of times specific categories of accommodations were included in 2013-2014 published research is summarized in Table 9. Presentation accommodations were the most frequently studied category (n=22), and within this category the most common accommodation was oral delivery--including human reader and various technology approaches (e.g., text-to-speech)--followed by computer administration (n=6). The second most frequent category studied was scheduling accommodations (n=17); all of these studies examined extended time. One study (Lewandowski, Lambert, Lovett, Panahon, & Sytsma, 2014) included breaks from testing as an additional scheduling accommodation. Several studies (n=19) analyzed accommodations from more than one category. A complete listing of accommodations examined in each study is provided in Appendix E.

Table 9. Accommodations in Reviewed Research

| Accommodations Category | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| Presentation | 22 |

| Equipment/Materials | 9 |

| Response | 12 |

| Timing/Scheduling | 17 |

| Setting | 11 |

| Multiple accommodations | 19 |

The findings of the studies about accommodations published in 2013 and 2014 are summarized according to the nature of the studies, in keeping with the range of their purposes and focuses. The findings included sets of research about specific accommodations: oral delivery, computer administration, extended-time, calculator, and aggregated sets of accommodations commonly called "bundles." We also report the findings about unique accommodations--those examined in only one study--including word processing, computer display screen and font color, three (instead of four) response options, students reading test items aloud, noise-reducing headphones, and student familiarity with test administrator. We also report about accounts of perceptions about accommodations, including those of student test-takers as well as educators and parents. We summarize the findings of the accommodations, and describe a range of implementation conditions as well as incidence of use of various accommodations across large data sets. The findings from studies in postsecondary educational contexts, which have grown over time from 6 to 11 in past reports, to 15 studies in this report, are given separate attention. This report also presents findings by academic content areas: math, reading, science, and writing. In Appendix F, we provide substantial detail about individual studies.

Research examining the effects of accommodations on assessment performance for students with disabilities comprised 25 studies published in 2013 and 2014 (see Figure 4; see also Appendix F, Table F-1, for details about each study of this type). We report the effects of these four discrete accommodations--oral delivery, extended time, calculator, and separate/specialized setting--along with a list of aggregated accommodations and uncommon accommodations.

Figure 4. Effects of Specific Accommodations (n=25)

Note: Three studies examined the effects of accommodations in general, but did not specify comparisons of individual accommodations with one another.

Oral delivery, provided using text-to-speech devices or human reader, was the single most investigated accommodation in 2013-2014, in seven different studies. For clarity in this report, as in the previous report (Rogers et al., 2014) we used "oral delivery" in place of "read aloud" to recognize the range of media formats used, including human readers, recordings of assessment items or instructions, and text-reading software or text-to-speech devices. The delivery methods that do not use human delivery ("read aloud") of the accommodation have continued to receive increased attention in research.

Of the six studies investigating oral delivery, two studies (Brumfield, 2014; Li, 2014) supported differential benefits for students with learning disabilities when receiving oral delivery (over not receiving accommodation), in comparison to students without disabilities. Three studies supported performance improvements for study participants including both students with and without disabilities. Only one study indicated no significant benefits: Meyer and Bouck (2014) reported that the small group of participants with learning disabilities did not show higher comprehension scores when receiving text to speech, nor higher oral reading fluency scores, although when asked, the participants perceived accommodations benefits. Researchers suggested potential factors affecting the score improvements. For instance, Buzick and Stone (2014) reported that grade level of participants and the ways that the accommodations were provided mitigated the variability of the effect sizes in their meta-analysis. Fincher (2013) indicated that poor reading skills for grade 4 students with and without disabilities had a role in the higher degree of benefit of oral delivery in reading, as well as the setting in which students were educated (e.g., time in general education settings), among other factors. Li (2014) noted in a meta-analysis that the strongest factors for oral delivery's effects included when in-person readers delivered the oral test administration, when students were in elementary school, and when extra time was concurrently permitted along with oral delivery (in comparison with oral delivery alone). Worland (2014) concurred with the larger benefits of oral delivery for younger students--grade 3 versus grade 5--and also when students were producing narrative writing.

The four extended-time accommodation studies engaged students at the postsecondary level in investigations about the impact of this accommodation on academic performance. All four had comparison groups of students without disabilities. All four studies' researchers reported that the accommodations provided did not differentially support students with disabilities (ADHD)--either learning disabilities or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder--in comparison with students without disabilities. Two studies (Lewandowski et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2013) examined comparisons between employing 150% time and 200% time, that is, one-and-a-half times to twice as much time as was used in the non-accommodated condition. One of these (Lewandowski et al., 2013) found that students with learning disabilities scored significantly better in the longer extended-time condition than in the shorter time frame, and the other (Miller et al., 2013) found that there was no difference, on average, for students with ADHD in number of items correct based on the time spans allowed. However, when comparing participant groups in terms of the number of items attempted and completed, some studies diverged. Lewandowski and colleagues (2013) indicated that students without disabilities completed more items and got more correct responses than students with learning disabilities. Similarly, May and Stone (2014) indicated that students with learning disabilities completed fewer items and skipped answering more items than did students without disabilities in both test conditions. Conversely, Miller and colleagues (2013) indicated that students with ADHD attempted and completed more items when using extended time than students without disabilities not using accommodations. Wadley and Liljequist (2013) indicated that students with ADHD used about the same amount of time for math placement testing, whether they were told that they had the standard administration time or the extended-time accommodation.

The two studies (Russell, 2014; Yakubova & Bouck, 2014) examining the impact of calculators both compared the performance of students with disabilities using and not using calculators, without a comparison group of students without disabilities. Both studies found that students with disabilities benefited from calculator use on their state mathematics assessment (Russell, 2014) and items involving computation and word problem solving (Yakubova & Bouck, 2014). Additionally, Russell (2014) found that students with learning disabilities in various special education placements all benefited similarly and not to differential degrees when using the calculator accommodation. Yakubova and Bouck (2014) reported that students with mild intellectual disabilities, while a small participant sample, experienced varying benefits and preferences between the scientific calculator and the graphing calculator.

Both studies examining setting accommodations (Lin & Lin, 2013; Lin & Lin, 2014) reported that there was no significant evidence indicating a benefit of separate, low-distraction setting for exceptional students--students with disabilities and English learners--on large scale assessments. Lin and Lin (2013) reported that English learners (ELs) with learning disabilities, and students with learning disabilities who were not ELs, did not score differently on math assessments than all students with learning disabilities. Lin and Lin (2014), examining a separate data set, found that there were no significant benefits for students with learning disabilities using separate settings during either reading or math assessments, at least not benefits that could be shown separate from being male, speaking a language other than English at home, and having less positive attitudes toward learning reading and math.

Only one study (Overton (2013) yielded findings pertaining chiefly and expressly to an aggregated set, or bundle, of accommodations. This researcher reported that grade 5 students with reading-related difficulties and disabilities had no significant score differences when using a combination of student reading aloud with unlimited time, in comparison to reading silently with unlimited time. As a result of finding interaction effects when analyzing data with the accommodation and the text type as factors, the findings suggested that students with reading difficulties and disabilities could benefit from reading narrative text aloud, but expository text silently.

We classified 10 studies as having investigated the impact of unique accommodations (i.e., accommodations that were the focus of just one study during the two years included in this report). Four studies indicated that the unique accommodations supported improved performance for students with disabilities: three response options (Freeman, 2013), noise-reducing headphones (Smith & Riccomini, 2013), familiar test administrators (Szarko et al., 2013), and integrated object representation (Zhang et al., 2014). Three studies yielded that the unique accommodations did not support improved performance for students with disabilities: word-processing for writing essays--although students did indicate preference for word-processing over handwriting (Berger & Lewandowski, 2013); American Sign Language (ASL; Cawthon & Leppo, 2013); and item format adaptations such as visuals and page layout (Cawthon et al., 2013a). Finally, the other three studies pertained to comparing forms of presentation accommodations. Two studies showed that there were no significant differences in performance between accommodations compared: black screen/white print and white screen/black print (Botello, 2014), and virtual versus physical manipulatives for students with low prior geometry knowledge (Lee and Chen, 2013b). One study showed very few differences in the effects of accommodations--that is, for the literal form (rather than the interpretive form) of parenthesis in audio presentation rules (Higgins & Katz, 2013).

Figure 5 displays the data for the 21 studies on perceptions about accommodations. More than one-half of them (n=12) provided findings about student perceptions only, while one-third (n=7) provided findings about educator perceptions only, and two studies (Lewis & Nolan, 2013; Torres, 2014) reported about accommodations perceptions indicated by more than one participant group.

Eight of the 12 studies on student perceptions (only) found that most or all participants viewed accommodations as helping them perform better on assessments (Berger & Lewandowski, 2013; Lewandowski et al., 2014; Lovett & Leja, 2013; Meyer & Bouck, 2014; Schreuer & Sachs, 2014; Stein, 2013; Stone, 2013; Wizikowski, 2013). One of these studies (Meyer & Bouck, 2014) also indicated that accommodations supported students while taking assessments by benefiting them in other ways, and that same study found that there was no significant performance benefit for using the accommodation despite students' perceptions. Further, of the eight studies that found favorable impressions about accommodations among its student participants, three studies (which included both students with disabilities and students without disabilities) indicated that both groups had similar perceptions (Berger & Lewandowski, 2013; Lewandowski et al., 2014; Lovett & Leja, 2013). One study offered feedback for improving the accommodations studied (Higgins & Katz, 2013). In five studies (Lovett & Leja, 2013; Lyman, 2013; May & Stone, 2014; Smith, 2014; Stein, 2013), researchers also inquired about circumstances or conditions for accommodations provision, including students' challenges in benefiting from accommodations. Finally, one study (Higgins & Katz, 2013), a study of math accommodations, observed that students preferred some accommodation strategies over others. There was a preference for interpretive forms of audio presentation for some math terminology and features such as exponents and tables, and the literal form for parentheses; there were also differences of opinion between students with and without disabilities about some audio presentation rules and features.

Figure 5. Accommodations Perceptions (n=21)

About half of the studies of educators' perceptions of test enhancements (accommodations and modifications) found that educators believed that they were beneficial to student test-takers' performance (n=3: Cawthon et al., 2013b; Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013; Zebehazy & Wilton, 2014), and to students' emotional state and self-esteem (Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013). Two studies (Alkahtani, 2013; Zebehazy & Wilton, 2014) indicated that some educators had less than favorable attitudes toward accommodations. Specifically, during the interview phase of the study, Alkahtani found that educators had a complicated view of assistive technology; they believed that it can provide access to the curriculum, but that students can also become overly dependent on assistive technology for learning. Zebehazy and Wilton reported that most respondents, who were teachers of students with blindness and visual impairments, perceived that tactile graphics were not appropriately adapted; however, the study did indicate that these teachers thought that they could make tactile graphics understandable and usable. Another study (Hawpe, 2013) found that willingness to provide some accommodations and modifications differed in degree among general and special educators. Yet another study (May, 2013) indicated that the survey respondents' knowledge, attitudes, and intent were not all aligned in a correlated manner, particularly that knowledge is not significantly associated with intent to provide accommodations.

Many of the studies of educator perceptions also reported findings about educators' knowledge, based on either assessment of accommodations facts and state guidelines (n=4: Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013; May, 2013; Young, 2013; Zebehazy & Wilton, 2014) or self-reported levels of awareness (Alkahtani, 2013). In these four studies, educators at various levels were reported to have widely varying levels of knowledge about accommodations based on their responses to questionnaires; K-12 teacher participants demonstrated a higher degree of knowledge than did postsecondary faculty members and advisors. Alkahtani reported that nearly all participants, both general and special educators, estimated their knowledge of assistive technology as mostly low, and their preparation to provide assistive technology as poor or absent. Most of the studies (n=6: Alkahtani, 2013; Cawthon et al., 2013b; Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013; Hawpe, 2013; Young, 2013; Zebehazy & Wilton, 2014) also reported about current accommodations practices acknowledged by educators.

Two studies examined the perceptions of multiple groups. In the study that reported details about the perceptions of students as well as educators (Lewis & Nolan, 2013), students and educators concurred about their perceptions of the helpfulness of the separate setting (e.g., small group, individual administration) accommodation, including supporting their assessment performance, yet also identified ways in which the separate testing setting could be improved. A single study (Torres, 2014) engaged the perspectives of students with autism, their parents, and the students' disability services provider; the researcher reported these perspectives in general and as they applied to academic accommodations use, finding positive perceptions about use of extended time and separate low distraction setting, and challenges of self-disclosing and advocating for accommodations. (See Appendix F, Table F-1 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

Sixteen studies reported findings about incidence of accommodations use and implementation-related matters. Ten studies (Alkahtani, 2013; Barnhill, 2014; Cawthon et al., 2013b; Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013; Hawpe, 2013; Leppo et al., 2014; Newman & Madaus, 2014; Schreuer & Sachs, 2014; Stein, 2013; and Wizikowski, 2013) detailed use patterns as reported by study participants. Almost half of these studies (n=5: Alkahtani, 2013; Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013; Hawpe, 2013; Leppo et al., 2014; and Nees & Berry, 2013) presented assessment accommodations use only in the primary and secondary education levels. These five studies' findings varied in their scope, with one study (Leppo et al., 2014) reporting that students with deafness and hearing impairments used similar accommodations, regardless of whether they also had other disabilities. Other studies described several accommodations in frequent use at the secondary level (Hawpe, 2013), and the five most common accommodations used in middle schools: extended time, separate setting, small group administration, directions or items read-aloud, and frequent breaks (Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013). The use-related findings from some studies at the postsecondary level indicated that the most common accommodations provided during examinations were extended time, and separate and specialized setting (Barnhill, 2014; Newman & Madaus, 2014; Stein, 2013); one study (Schreuer & Sachs, 2014) reported extended time and alternate formats were the most common. Additional postsecondary findings were that accommodations were offered at a much lower rate than at the secondary level (Cawthon et al., 2013b; Newman & Madaus, 2014). Wizikowski (2013) estimated a much higher rate of exam-related accommodations--approximately 73 percent--compared to these lower rates.

Six studies (Abedi & Ewers, 2013; Klehm, 2014; Nees & Berry, 2013; Smith, 2014; Young, 2013; and Zebehazy & Wilton, 2014) provided findings about accommodations implementation practices and issues. These studies offered few common themes. For instance, two studies (Abedi & Ewers, 2013; Klehm, 2014) discussed the purposes of accommodations--including eliminating the effects of disability during testing--and how implementation can limit the validity of testing. Nees and Berry (2013) reported on the expanding implementation of audio assistive technology for students with visual impairments, and the implementation difficulties such as technical concerns and preparation of educators. Smith (2014) reported postsecondary students' consideration of practices in their experience, describing personal development issues, chiefly learning interdependence, connected with accommodations practices as they transition from secondary to postsecondary education. Young (2013) described how different approaches to postsecondary advising lead to differing degrees of attention to the underlying needs of students for accessing accommodations. Zebehazy and Wilton (2014) reported on the implementation of tactile graphics for students with visual impairments, from the perspective of their teachers, including that the best presentation format is a combination of tactile graphics with written explanations. (See Appendix F, Table F-1 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

In Figure 6, we report on the six studies (Cawthon et al., 2013a; Finch & Finch, 2013a; Finch & Finch, 2013b; Huggins & Elbaum, 2013; Lewandowski et al., 2013; Stone, 2013) that provided findings about academic construct validity when accommodations were used on large-scale assessments. Five studies reported findings pertaining to reading, including one study (Cawthon et al., 2013a) that examined the constructs of English language arts and science, and one study (Finch & Finch, 2013b) that examined reading and math assessments. Cawthon and her colleagues (2013b) indicated that the construct validity of both English language arts and science were complicated by item adaptations, according to most of the participant groups' performance scores. Finch and Finch (2013a, 2013b) investigated the use of multilevel Rasch mixture models for examining differential item functioning related to disabilities and accommodations, concluding that this was a successful approach, and finding concerns with assessment validity. Similarly, Lewandowski and colleagues (2013) found that extended time complicated the validity of reading comprehension performance for postsecondary students with and without learning disabilities. In contrast, Stone (2013) concluded that a two-stage condition-adaptive testing system simultaneously produced valid reading comprehension performance scores for students with reading disabilities when using oral delivery accommodations; these test-takers also produced oral reading fluency scores separately. As previously mentioned, math assessment validity was reported to be compromised when students with disabilities were provided accommodations (Finch & Finch, 2013b).

Figure 6. Construct Validity (n=6)

The construct validity of science assessments was examined in two studies (Cawthon et al., 2013a; Huggins & Elbaum, 2013). Cawthon and colleagues indicated construct validity concerns in science for elementary students. Huggins and Elbaum (2013) applied "score equity assessment" and indicated that the science assessment scores of older elementary students with disabilities using accommodations were more comparable to the general population of test-takers than were scores of students with disabilities not using accommodations. (See Appendix F, Table F-1 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

Fifteen studies reported findings about accommodations at the postsecondary education level. Researchers investigated effects of accommodations on test performance, test-takers' experiences using accommodations, and faculty members' perceptions of accommodations, along with implementation practices and uses of accommodations; seven studies each reported findings in two of these areas. The four studies examining accommodations effects included three studies on extended time (May & Stone, 2014; Miller et al., 2013; Wadley & Liljequist, 2013) and one study that was a meta-analysis of 19 studies about the effects of American sign language (ASL) spanning primary, secondary, and postsecondary education (Cawthon & Leppo, 2013). The three studies on the effects of extended time yielded convergent findings: there were no differential benefits for postsecondary students with disabilities.

Eleven studies provided findings about perceptions in postsecondary education; seven inquired only about students' perceptions and three inquired only about educators' perceptions, while one study reported about the perceptions of students, educators, and students' parents. The findings of the seven studies (Lewandowski et al., 2014; Lyman, 2013; May & Stone, 2014; Smith, 2014; Stein, 2013; Torres, 2014; Wizikowski, 2013) about postsecondary students' perceptions were complex and diverse. Many studies indicated that students perceived accommodations as generally supportive, yet the researchers often sought additional information about the limits to accommodations at the postsecondary level. Students with disabilities were significantly more positive than students without disabilities about separate room test setting, but both students with and without disabilities indicated that their performance would be improved if using extended time, separate exam rooms, extra breaks, and word processors (Lewandowski et al., 2014).

Students at the postsecondary level with various disabilities believed that accommodations could be helpful, yet also detailed several barriers to accessing accommodations. The barriers included: students' own concerns about how they were perceived by other students and by themselves as well, limited knowledge of their professors about accommodations, and resource limitations in their universities (Lyman, 2013). Students with learning disabilities were not affected by stereotype threat, a concern about potentially confirming stereotypes about themselves and other students with learning disabilities. In other words, these postsecondary students did not appear self-conscious about their need for or use of accommodations (May & Stone, 2014). Students with non-visible disabilities experienced developmental challenges as they transitioned from secondary to postsecondary education, including identity maturation, desiring credibility, and controlling information. All of these challenges were related to the students seeking and receiving accommodations (Smith, 2014).

Students with mental health related disabilities described their accommodations experiences, including the complexity of the separate quiet testing space in that it can decrease distress yet also remove opportunity to interact with course instructors (Stein, 2013). Academic stress, in this case experienced by students with autism spectrum disorders, was investigated by Torres (2014), who found that study participants experienced exam accommodations as supportive, yet the process to access them was socially challenging. Students with various disabilities across public and private universities indicated that exam accommodations were mostly useful and that their experiences were relatively satisfying; also, their perceptions were that accommodations knowledge by relevant university personnel was satisfactory (Wizikowski, 2013).

The three studies reporting on the perceptions of postsecondary faculty and other personnel yielded varying findings: positive perceptions about interpreter, captioning, and speech-to-text technology accommodations (Cawthon et al., 2013b); slightly positive intent of nursing faculty members to provide accommodations in general (May & Stone, 2014); the academic advisors' approach had an impact on their involving disability services' accommodations resources (Young 2013). Finally, one study (Newman & Madaus, 2014) provided findings on the perceptions of students, their disability services provider, and their parents. This study found, in part, that about half of the student participants perceived that they were no longer in need of accommodations and that they in fact did not have disabilities any longer.

Four studies reported on use patterns and implementation practices for students with disabilities at the postsecondary level. Two studies had contradictory findings about the use frequency of accommodations during course examinations by students with disabilities, with Newman and Madaus (2014) estimating rates of less than 10 percent for students early in their postsecondary experience (e.g., reader for tests and assignments: 4%), and Wizikowski (2013) reporting that about 73 percent of study participants reported using exam accommodations at some point during their postsecondary education. The former study (Newman & Madaus) gathered information from students at a different point in their postsecondary experience than the latter study (Wizikowski), which might partially explain the difference in findings. The other two studies reported on the manner by which accommodations were implemented in the postsecondary setting. Smith (2014) inquired about students' perceptions as well as how those perceptions affected the implementation of accommodations, and described students' reluctantly embracing interdependence on academic resources. Young (2013) examined the perspectives of academic advisors, and how their demographic characteristics and working circumstances interacted with their approaches to assisting students with disabilities in assessment accommodations. One finding was that advisors who used a prescriptive approach to advising were associated with failing to refer students with disabilities to disability services offices.

One study (Lovett, 2014) was a literature review about the implications of accommodations research in relation to the Department of Justice implementation guidelines on the Americans with Disabilities Act amendments of 2008, yielding a set of five major points. (See Appendix F, Table F-1 for more detailed explanation of findings of each study.)

As in previous reports, we analyzed findings according to the academic content area that was the focus of the research. We present findings for each content area according to the frequency with which the content areas were identified, with most prevalent content areas presented first: 15 studies in reading, 11 studies in mathematics, 4 studies in science, and 1 study in writing (see Figure 7). For each content area, we examined the impact of accommodations on assessment performance, perceptions about accommodations, construct validity of accommodated assessments, and implementation and use of accommodations. (See Appendix F, Table F-1 for more detailed explanation of the findings of each study.)

Figure 7. Findings by Content Areas (n=24)

Reading. The findings of the 15 studies in reading included those from 10 studies in reading only (Botello, 2014; Cawthon & Leppo, 2013; Finch & Finch, 2013a; Fincher, 2013; Lewandowski et al., 2013; Meyer & Bouck, 2014; Miller et al., 2013; Overton, 2013; Smith & Riccomini, 2013; Stone, 2013), those from three studies in reading and math (Buzick & Stone, 2014; Finch & Finch, 2013b; Li, 2014), those from a study in English language arts and science (Cawthon et al., 2013a), and those from a study in reading, math, and science (Freeman, 2013). All of these studies--except for Stone (2013)--reported on the effects of various accommodations during math assessments, and five of these 15 studies yielded other findings as well. Four studies (Cawthon et al., 2013a; Finch & Finch, 2013a; Finch & Finch, 2013b; Lewandowski et al., 2013) also reported about validity, and one study (Meyer & Bouck, 2014) also reported about student perceptions.

The accommodations and modifications benefited the reading performance of at least some students with disabilities in seven studies, especially in relation to comparisons with students without disabilities. These studies included three of the four oral delivery studies (Buzick & Stone, 2014; Fincher, 2013; Li, 2014), one study (Cawthon et al., 2013a) with various item adaptations, one study (Overton, 2013) on student reads aloud combined with unlimited time, one study (Smith & Riccomini, 2013) on noise-reduction headphones, and one study (Freeman, 2013) on three response options. One study (Miller et al., 2013) indicated that both students with and students without disabilities improved in both items completed and items correct across the standard administration and the two extended time conditions, suggesting that extended time did not differentially benefit students with disabilities. Another study (Lewandowski et al., 2013) reported that students without disabilities improved even more than students with disabilities when provided extended time. Also, one study (Finch & Finch, 2013b) showed that students improved in reading, but that there was a suspected validity concern complicating this finding. In contrast, three studies showed no significant benefit of accommodations for students with disabilities: for American sign language (in comparison to English print) (Cawthon & Leppo, 2013), for oral delivery (Meyer & Bouck, 2014), and for accommodations in general (Finch & Finch, 2013a). One study (Botello, 2014) which compared two screen and font color options for all students (with a subset of students with disabilities included), reported that there were no significant differences in comprehension across these conditions. Four studies also included findings on construct validity for reading assessments, reporting concerns about the construct validity of reading due to accommodations in general (Finch & Finch, 2013a, Finch & Finch, 2013b) and extended time (Lewandowski et al., 2013). Also, Cawthon and her colleagues (2013b) indicated that a set of item adaptations might have affected validity for part of the participant group. Finally, Stone (2013) reported that students with disabilities believed they scored better when using oral delivery than when they did not; further, the researcher concluded that the condition-adaptive assessment format was able to measure separate reading components without affecting test validity.

Mathematics. The findings of the 11 studies in math included those from seven studies in math only (Higgins & Katz, 2013; Ketterlin-Geller et al., 2014; Lee & Chen, 2014; Russell, 2014; Wadley & Liljequist, 2013; Yakubova & Bouck, 2014; Zhang et al., 2014), those from three studies in math and reading (Buzick & Stone, 2014; Finch & Finch, 2013b; Li, 2014) and those from a study in math, reading, and science (Freeman, 2013). Nearly all of these studies--except for Ketterlin-Geller et al. (2014)--reported on the effects of various accommodations during math assessments, and only two of these 10 studies yielded other findings: one study (Higgins & Katz, 2013) reported about students' perceptions, and one study (Finch & Finch, 2013b) reported about construct validity. The accommodations benefited the performance of students with disabilities in math in five studies, including both calculator studies (Russell, 2014; Yakubova & Bouck, 2014), one study on oral delivery (Li, 2014), one study on three response options (Freeman, 2013), and one study on integrated object representation (Zhang et al., 2014). In contrast, one study (Buzick & Stone, 2014) showed that there was a similar degree of benefit of the oral delivery accommodation for both students with and students without disabilities. Also, one study (Finch & Finch, 2013b) showed that students improved in math but that there was a suspected validity concern complicating this finding. Further, one study (Wadley & Liljequist, 2013) indicated that students with disabilities did not benefit from extended time. Two studies that compared versions of accommodations reported differing findings: Higgins and Katz (2013) indicated that only one audio presentation rule (pertaining to parentheses) showed a benefit in performance for students with disabilities, and Lee and Chen (2014) reported that there was no significant difference in performance between virtual and physical manipulatives.

Science. The findings of the four studies in science included those from two studies in science only (Brumfield, 2014; Huggins & Elbaum, 2013), those from one study in science and English language arts (Cawthon et al., 2013a), and those from one study in science, math, and reading (Freeman, 2013). These findings included those pertaining to performance effects, as well as validity. Three studies reported that, during science assessments, students with disabilities were supported to a greater degree than students without disabilities by oral delivery (Brumfield, 2014), by a set of format adaptations for grade 3 students (Cawthon et al., 2013a), by accommodations in general (Huggins & Elbaum, 2013), and by three response options (as opposed to four; Freeman, 2013). The validity findings were divided: Huggins and Elbaum reported that validity of the science construct was not affected by the accommodations that students received, and Cawthon and her colleagues (2013b) reported that the science construct may have been affected by the set of item format adaptations for part of the participant group.

Writing. There was a single study (Worland, 2014) providing findings related to writing. Worland reported that oral delivery during a writing assessment was supportive for students in grade 3, including students with learning disabilities. This study also reported about the impact of accommodations use related to writing genres.

The researchers of most of the studies (n=44) in this body of research literature discussed limitations that provided context for the results they reported. Table 10 presents the categories of limitations for the 101 limitations that were noted by researchers: methodology, sample characteristics, results, test/test context, and other. Of the 44 studies, 34 of them identified more than one category of limitation; the overall average was about two limitation categories per study.

Table 10. Categorized Limitations Identified by Authors

| Limitation Category | Number of Studiesa |

|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | 35 |

| Methodology | 22 |

| Test/Test context | 22 |

| Results | 18 |

| No limitation listed | 8 |

| Other | 3 |

a Thirty-four studies included more than one category of limitations, represented in 2 to 4 limitations categories.

The most commonly reported category of limitations in 2013-2014 studies was sample characteristics (n=35), which usually referred to the issue that the sample was smaller or narrower than intended or required. This issue yielded a challenge to population representativeness, limiting the generalizability of the findings beyond the research participants. The next most frequent categories (with 22 studies each) were limitations about methodology, and about test and test context. Methodology limitations referred to flaws in research design or practices. Test and test context limitations referred to the degree of authenticity of the testing circumstances, especially pertaining to accommodations. Limitations about results (n=18) indicated that confounding factors constrained the accuracy or consistency of the data, limiting the confidence readers should have about the study's results. (See Appendix G, Table 1 for additional details about the study limitations.)

The researchers of most of the studies (n=42) in the body of research literature included in this analysis discussed several future research directions that provided indicators of lessons they learned as well as their views of the next steps to take. Table 11 presents the categories of the 100 future research directions listed by researchers: methodology, sample characteristics, results, test/test context, and other. Of the 42 studies, 31 studies identified more than one future research direction category; the overall average was approximately two categories per study.

The most commonly reported category of future research directions in 2013-2014 studies was sample characteristics (n=32). Typical directions about sample characteristics were engaging different types of students to affirm or find exceptions to the current studies' findings. The second most common category was research ideas about test and test context (n=26), where researchers indicated the need for improvements in assessments in terms of accessibility, and the need for deeper understandings of how accommodations might support this goal. The third most frequently identified area for future research pertained to methodology (n=17), where researchers pointed to additional angles that could be taken to increase the field's knowledge and understanding about accommodations--sometimes suggesting qualitative methods to uncover meaning beneath quantitative findings. Research ideas about results (n=15) were just a little less common than those about methodology. These addressed investigating possible outcomes or aspects of the findings that could further explain them, often suggesting ways to address the limitations of the current studies' data. Finally, the "other" category included 10 studies with a variety of directions that were outside of the categories, such as inquiring about the effects of professional development for educators about accommodations (Hawpe, 2013; Klehm, 2014). (See Appendix G, Table 2 for additional details about future research directions.)

Table 11. Categorized Future Research Directions Identified by Authors

| Future Research Category | Number of Studiesa |

|---|---|

| Sample characteristics | 32 |

| Test/Test context | 26 |

| Methodology | 17 |

| Results | 15 |

| Other | 10 |

| No future research listed | 8 |

a Thirty-four studies listed directions for future research that fit into multiple categories, represented in 2 to 5 future research directions categories.

Top of Page | Table of Contents

This report provides a snapshot of accommodations research literature in 2013-2014. It addresses the types of accommodations that were studied, the purposes of the research, the research type, data sources, characteristics of the independent and dependent variables under study, comparability of findings between studies in similar domains, and limitations and directions of future research.

As in the past, mathematics and reading were the content areas most frequently addressed in the studies included in this analysis. Students were the participant group in about two-thirds of the studies. Students with learning disabilities (LD) were more likely to be included in the research samples than other groups, which was expected because LD is the more prevalent disability category.

Accommodations research continues to be an area where a substantial amount of research is occurring. There is interest in exploring a wide range of topics related to accommodations. For example, as more assessments shift from paper and pencil tests to technology-based assessments there are new issues and questions.

As in previous reports (Cormier et al., 2010; Johnstone et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 2002; Rogers et al., 2012; Rogers et al., 2014; Zenisky et al., 2007), the findings for a specific accommodation were often mixed. For example, for the oral delivery accommodation, two studies found a differential boost for students with disabilities when compared to students without (Brumfield, 2014; Li, 2014), three found performance improvements for both students with and without disabilities (Buzick & Stone, 2014; Fincher, 2013; Worland, 2014), and one found no significant benefits (Meyer & Bouck, 2014).