Planning Alignment Studies For Alternate Assessments Based on Alternate Achievement Standards

Policy Directions 20

Shawnee Y. Wakeman • Claudia Flowers •

Diane Browder

University of North Carolina at

Charlotte

November 2007

All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Wakeman, S., Flowers, C., & Browder, D. (2007). Planning alignment studies for alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards (Policy Directions 20). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Policy20/

Introduction

States planning to conduct alignment studies on their alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS) typically must make several decisions in addition to the alignment model to be used. (See Policy Directions Number 19 for complications in conducting alignment studies on AA-AAS and alternative models that may be used.)

There are several components to consider when planning an alignment study, and specific questions to ask for each component. Guidance is also needed to maximize resources spent to determine the alignment of a state’s alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards (AA-AAS) with grade-level content standards.

The purpose of this Policy Directions is to provide states with information on the components to consider with an external vendor when planning a study of the alignment of alternate assessment based on alternate achievement standards with grade-level content standards. It also address guidance for maximizing resources spent to determine alignment of the AA-AAS.

Planning with an External Vendor

Due to time and expertise requirements of alignment studies, and the benefits of impartial reviews, states often seek assistance from a vendor to complete their studies of the alignment of alternate assessments based on alternate achievement standards to grade-level content standards. Specific issues should be considered about planning the study at the time states seek bids from vendors. First is the guiding principles to convey to the vendors so that the state’s own priorities are reflected in the study. Leading researchers on assessment and accountability, such as Robert Linn at the University of Colorado, have consistently supported the need for accountability systems to be guided by specific principles such as validity, fairness, credibility, and utility.

For alternate assessments, Brian Gong of the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessments noted the need to articulate the development of content standards and any extended standards, a focus on the purpose of the assessment, and a well thought out prioritization of content for the population of students who participate in AA-AAS. With these principles in mind, states may want to address the following questions with a stakeholder group prior to negotiating the alignment study with a vendor:

1. Background. What are the policy elements working within the alternate assessment system (for example, a rationale for the prioritization of content standards; the purpose of the AA-AAS system)?

2. Purpose. What does the state want to accomplish by conducting the alignment study (for example, to study a new AA-AAS format, the link between alternate achievement standards and the content standards, the link between instruction and standards or the assessment)?

3. Participants. Who should be included in the development or prioritization of content standards, alternate assessment items, or alignment issues (including standards setting practices)? Are content experts, special educators, measurement or test development experts, and possibly parents or advocates involved in these steps?

4. Assessment Characteristics. What are the unique issues surrounding the state’s AA-AAS that can influence alignment outcomes? How does the assessment approach influence the alignment methodology?

After defining the principles and characteristics of the state’s alternate assessment and the goals for the alignment study, the next step is to review with potential vendors the components of alignment (see Policy Directions 19) to be included in the study. Some negotiation should occur about how much more will occur besides the simple horizontal alignment of standards and the assessment. Will alignment of extended standards occur? Will the alternate assessment be aligned to these extended standards (if confirmed to align to the state standards)?

Additionally, the following specific questions need to be answered to ensure that the study will meet the state’s expectations:

• Who will be used as reviewers? How many reviewers will be used? How will reliability measures be provided about the ratings?

o Evaluative criteria: More than one reviewer should be used so that reliability can be checked. Content area experts are needed to determine the relationship between standards and the assessment. Special educators may be needed to consider other components.

• What are the educational elements that will be included in the alignment study?

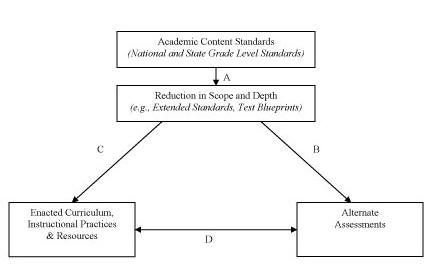

o Evaluative criteria: The study must include the relationship of standards and the assessment. Consideration of other factors (see Figure 1) should be discussed.

• If student work is included in the alternate assessment, how will the state be sampling the evidence to determine the alignment?

o Evaluative criteria: There should be a clear plan for a representative sample.

• What data will be reported (both qualitative and quantitative)?

o Evaluative criteria: The data should provide information that not only will address the U.S. Department of Education Peer Review criteria, but also can be used for future development of the assessment system.

• What criteria will be applied in evaluating the extent of the alignment?

o Evaluative criteria: Information should be provided on criteria to be used in judging qualities such as range, balance, depth of knowledge, and overlap across grade levels.

• Will the vendor provide any potential reasons for any lack of alignment?

o Evaluative criteria: For future planning it will be helpful to know why items did not align. For example, is there simply misidentification of the correct standard or is the item not even academic?

Figure 1. Paths Between the Educational Components of an Alternate Assessment System

Getting the Most from an Alignment Study

Alignment studies require the investment of time and financial resources by the state. While this investment can help the state meet the requirements of the U.S. Department of Education Peer Review, it also is important to consider ways to get more from this investment. This "something more" should focus on the ongoing quality enhancement of education services for students participating in alternate assessments. The following recommendations are offered for increasing the return on the investment in an alignment study.

Involve stakeholders in planning and responding to the alignment study.

Services for students with more significant disabilities have been changing rapidly as educators discover new ways to promote learning general curriculum content. Not all stakeholders are familiar with these advances. Others may worry that these advances compete with promoting functional life skills. Or, they want to be sure that the alternate assessment promotes best practice for students such as self determination, assistive technology, generalization, and inclusion. It is important for stakeholders to have the opportunity to become familiar with current federal policy requiring AA-AAS to link to grade level standards.

Consider the cost-benefit of including instructional alignment in the study.

States sometimes do not include instructional alignment in their study of alignment to content standards because it is not required for the U.S. Department of Education Peer Review, has additional costs, and may simply provide evidence of what is already known (that teachers have not yet had adequate professional development in access to the general curriculum). However, information on instructional alignment may provide powerful information for planning professional development. For example, the use of a curriculum survey can help identify whether teachers need help broadening their academic focus (for example, to move beyond money skills in math) or promoting increased depth of knowledge (for example, to extend beyond simple exposure or basic awareness).

A review of professional development materials can reveal whether teachers are receiving adequate information on how to align instruction with state standards. This instructional alignment may also be the most important piece to stakeholders because it can provide information on whether the overall system promotes a quality educational program.

Use the alignment study to look at inferences about student learning.

One purpose of an alternate assessment as prescribed by current federal policy is to determine whether students have made adequate yearly progress on state standards in language arts and math, and to document their performance in science. An alignment study can help to answer the question of whether the assessment system can actually answer this question. For example, what "counts" in the scoring of the alternate assessment? Does the system focus on students showing what they know or simply being present in a program that meets certain quality indicators? Also, the evidence from the alignment study can be used to consider what areas of the curriculum are not being well-addressed in assessment and instruction. For example, if teachers helped create the assessment items, and there is poor alignment in science, there is an obvious need for further development of the assessment before inferences can be made that the students are learning science.

Summary

A well planned alignment study can ensure that the state’s guiding principles are preserved and the investment in the alignment study can be optimally used for improvement of the overall system. This builds on the basic information on issues that states should consider in the design of an alignment study.

Resources

Aligning Tests with States’ Content Standards: Methods and Issues. Bhola, D. S., Impara, J. C., & Buckendahl, C. W. (2003). Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 22, 21-29.

Alignment: Policy Goals, Policy Strategies, and Policy Outcomes. Baker, E. L., & Linn, R. L. (2000). Retrieved July 8, 2005, from http://www.cse.ucla.edu/products/newsletters/cresst_cl2000_1.pdf

Designing Content Targets for Alternate Assessments in Science: Reducing Depth, Breadth, and/or Complexity. Gong, B. (2007). Presentation at the Web seminar Best Practice and Policy Consideration in Science Teaching and Testing for Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities. Retrieved March 28, 2007, from http://www.nceo.info/Teleconferences/tele14

Horizontal and Vertical Alignment. Case, B. J., & Zucker, S. (2005). Retrieved June 5, 2005, from http://harcourtassessment.com/hai/Images/pdf/assessmentReports/HorizontalVerticalAlignment.pdf

State Standards and State Assessment Systems: A Guide to Alignment. La Marca, P. M., Redfield, D., & Winter, P. C., Bailey, A., & Despriet, L. H. (2000). Retrieved June 6, 2005, from http://www.ccsso.org/content/pdfs/ALFINAL.pdf

Top of page