Student

Perspectives on the Use of Accommodations on Large-scale Assessments

Minnesota Report 35

Published by the National Center on

Educational Outcomes

Prepared by Sandra Thompson,

Martha Thurlow, and

Lynn Walz

December 2000

Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and

distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Thompson, S., Thurlow, M., & Walz, L. (2000). Student

perspectives on the use of accommodations on large-scale assessments (Minnesota

Report No. 35). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational

Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web:

http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/MnReport35.html

Overview

The 1997 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities

Education Act (IDEA 97) requires students with disabilities to be included in statewide

and district-wide assessments, with appropriate accommodations where necessary.

Participation of students with disabilities in large-scale assessments is critical to

ensure that schools and other educational systems are held accountable for the educational

performance of these students and to obtain a representative and accurate understanding of

overall student performance. Federal legislation, such as Goals 2000, the Improving

America’s School Act (IASA), and IDEA 97, require all students, including those with

disabilities, to be included in all large-scale assessment programs by taking general

assessments with or without accommodations, or by participating in alternate assessments.

IEP teams make decisions about how students will participate in

large-scale assessments. According to IDEA, students who are planning for the important

transition from school to adult life must be invited to attend their IEP team meetings,

and their interests and preferences must be considered in the development of their

transition plans. As team participants, students with disabilities need to have an active

and informed role in making decisions about the use of accommodations for tests, for

instruction, and for their future adult lives.

Accommodations

Research Findings

Currently, every state has a policy governing the use of

accommodations on large-scale assessments (Thurlow, House, Boys, Scott, & Ysseldyke,

2000). These policies vary widely across states, which may account partially for the wide

range in both the number of students using accommodations and the variety of

accommodations selected (Thompson & Thurlow, 1999). Some states allow the use of test

accommodations only for students with disabilities and 504 accommodation plans, while

others encourage the use of accommodations for any student who needs them. While the

specific accommodations listed by states has continued to increase over time, Thurlow et

al. (2000) noted the tendency of many states to list as “accommodations”

practices that might be more appropriately considered to be good test-taking habits (e.g.,

use of pencil grips or well-sharpened pencils, facing the front of the room).

Assessment accommodations are defined by Schulte, Elliott, and

Kratochwill (2000) as “any change in an assessment that is intended to maintain or

facilitate the measurement goals of the assessment so scores from the accommodated test

measure the same attributes as scores from the unaccommodated test” (p. 2).

Researchers argue that accommodations should raise or “boost” performance of

students who need them, and not affect the performance of students who do not need them

(Fuchs, Fuchs, Eaton, Hamlett, & Karns, 2000; Tindal, Helwig, & Hollenbeck, 1999).

The National Research Council’s (1998) report on high stakes

testing identifies issues and recommendations on participation and accommodations for

students with disabilities. It recognizes that testing accommodations should be offered to

increase the participation of students with disabilities in large-scale assessments and to

obtain valid information about student performance. The report suggests that decisions

about how students with disabilities participate in large-scale assessments (particularly

when the stakes are high) be guided by systematic and objective criteria.

There are an increasing number of empirical studies about the use

of testing accommodations (Bielinski, Ysseldyke, Bolt, Friedebach, & Friedebach, in

press; Elliott, Bielinski, Thurlow, DeVito, & Hedlund, 1999; Trimble, 1998) and about

their effects (Thurlow, Hurley, Spicuzza, Erickson, & El Sawaf, 1996; Thurlow,

Ysseldyke, & Silverstein, 1995; Tindal & Fuchs, 2000). This increase is partially

due to policy and the increasing use of high stakes assessments in many states. In

addition, federal funds have begun to be directed toward the use and effects of testing

accommodations. (Erickson, Thurlow, & Ysseldyke, 1996). There is also research that

addresses IEP team decisions about accommodations.

Role of the IEP Team in the

Selection and Use of Assessment Accommodations

IEP teams have the authority to select accommodations for students

with disabilities (Heumann & Warlich, 2000). A study by Fuchs, Fuchs, Eaton, Hamlett,

and Karns (2000) found that IEP teams often offer students too many accommodations,

“crossing their fingers” that something will help, and then finding little, if

any, improvement in assessment performance. Similarly, Hollenbeck, Tindal and Almond

(1998) found a great deal of variability in the perceptions of teachers about appropriate

assessment accommodations.

Although IEP teams select the assessment accommodations for

individual students, many states provide a list of accommodations to help IEP teams in

this selection. Some states post this list on

Web sites or on the IEP form itself (Thompson, Thurlow, Quenemoen, Esler & Whetstone,

2001). Less often evident on the forms are the possible consequences of the use of certain

accommodations, especially those that may jeopardize test validity (e.g., scores do not

count for graduation if the accommodation is used, etc.).

Minnesota’s Basic Standards

Tests

Minnesota requires students to pass basic skills tests in Reading,

Writing, and Math to graduate from high school. Basic Standards Tests in Reading and Math

are first administered to students in eighth grade. Students who entered ninth grade in

the 1996-97 school year (anticipated graduating class of 2000) were required to pass Basic

Standards Tests in Reading and Math to be eligible for graduation. The graduating class of

2000 was required to respond to 70% of the test items accurately to pass the tests.

Graduates in 2001 are required to achieve 75% accuracy. Students may retake the Basic

Standards Tests at least twice annually until a passing level is achieved. A test in

Written Composition is administered to students beginning in tenth grade.

Students with IEPs or Section 504 accommodation plans are eligible

for accommodations on the Basic Standards Tests in Reading, Math, and Written Composition.

In the state guidelines, a testing accommodation is defined as an adjustment in testing

conditions or a change in the method of administering the test that does not:

• Alter the validity or reliability of the

state standard,

• Compromise the security or the

confidentiality of the tests, or

• Render the student’s score

incomparable to the scores of those students who took the tests under standard conditions.

In Minnesota, decisions about appropriate testing accommodations

for students with disabilities are made and annually reviewed by the IEP or 504 team and

documented on each student’s IEP or 504 accommodation plan. Accommodations on the

Basic Standards Tests typically fall into four categories – presentation format, test

setting, scheduling or timing, and response format.

Decisions about the accommodations or modifications students use

during testing affect notations on their progress records. Students who either take the

state tests as generally administered, or with accommodations as needed, receive a

standard diploma and a notation that they passed at the “state level” on their

high school transcript. Students who take a modified version of the tests (e.g., by using

a non-approved testing change called a modification) also receive a standard diploma, but

have the notation “pass-individual” on their high school transcript.

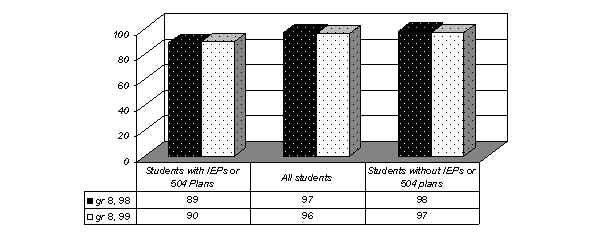

Participation of students with disabilities on Minnesota’s

Basic Standards Tests is high, about 90% in 1998 and 1999 (see Figure 1). Still, as shown

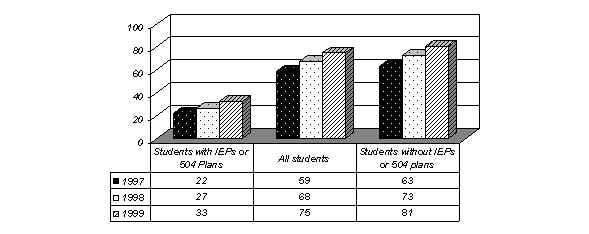

in Figure 2, overall performance lags far below that of students without disabilities

(Thompson, Thurlow, & Spicuzza, 2000).

Figure 1. Participation Rates of 8th Grade Students with

Disabilities on Minnesota’s Basic Standards Tests in 1998 and 1999

Figure 2. Passing Rates of 8th Grade Students with Disabilities on

Minnesota’s Basic Standards Reading Test from 1997 to 1999

Role of the Student in the Selection and

Use of Assessment Accommodations

Educators, and more recently, IEP teams have the responsibility of

making educational decisions for students. We have now moved into what Bersani (1995)

referred to as the “third wave” in the disability movement in which consumers of

special education services are invited to the table as self-advocates. In the past, if a

student did not attend his or her IEP team meeting, decisions about assessment

accommodations were likely to be made without his or her input with the assumption that

whatever decision was made would be followed without question by the student. Common sense

is beginning to prevail as people realize that, disability or not, adolescents seldom

follow directions without question, especially when they might “stand out” from

their peers (Kaiser & Abell, 1997). According to Lichtenstein (1998), “the search

for independence and the struggle for autonomy” (p. 9) is at the top of the list of

major changes for adolescents.

Focusing on the role of the student in the selection and use of

assessment accommodations is critical. In a study about the use of assessment

accommodations by students with limited English proficiency, Liu, Anderson, Swierzbin and

Thurlow (1999) found that the actual use of assessment accommodations varied greatly

depending on the student and what he or she was comfortable using. It is not enough to

have students simply attend their IEP meetings and listen to others make decisions about

them; teachers and parents need to take an active role in preparing students for their

participation in state and district assessments. Some students have had limited experience

in expressing personal preferences and advocating for themselves. Speaking out about their

preferences, particularly in the presence of “authority figures,” may be a new

role for students, one for which they need guidance and feedback. Research has shown that many students with

disabilities have limited knowledge of their strengths and weaknesses. (Agran, Snow &

Swaner, 1999; Kaiser & Abell, 1997; Martin & Huber Marshall, 1997). According to

Field, Hoffman and Posch (1997), “the potential for self-determination is directly

proportional to the individual’s awareness of his or her strengths, weaknesses,

needs, and preferences” (p. 288).

Field and Hoffman (1994) define self-determination as “the

ability to identify and achieve goals based on a foundation of knowing and valuing

oneself” (p. 164). Another term commonly used is “self-advocacy,” which

involves making informed decisions and then taking responsibility for those decisions (Van

Ruesen, Deshler, & Shumaker, 1989). Winnelle Carpenter, a self-advocate and

accommodations consultant from Minnesota, describes the process of self advocacy as

follows:

For

students with disabilities to self advocate effectively, they must understand their

specific disability; learn their strengths and challenges; identify factors that are

interfering with their performance, learning, and employment; and develop compensations,

accommodations and coping skills to help them succeed. In addition, through careful

guidance, these same students must learn how to apply this knowledge effectively when

making decisions, negotiating and speaking up on their own behalf. (Carpenter, p. iv,

1996)

The goal is for students to assume control, with appropriate

levels of support, over their assessment participation and select and use accommodations

that are most helpful to them, both in the assessment and throughout their daily lives.

In this study, we interviewed 96 high school students with

disabilities about their participation in a large-scale statewide test that they must pass

in order to graduate from high school with the standard notation that they passed at the

state level. We wanted to know whether they had participated in the statewide assessments

and whether they had passed tests in Reading, Math, and Writing. We also asked the

students what accommodations they used for statewide testing, in their daily classes, and

what accommodations they thought might be most helpful to them in the future. This paper

presents the results of the study from the student perspective, along with recommendations

for future research and practice.

Method

Participants and Setting

Interviews for this study took place at a day-long conference on

transition planning and self advocacy for high school students with disabilities from

across the state of Minnesota. The “Minnesota Mind Movers” conference was held

in conjunction with the International Conference on Learning Disabilities. The purpose of

the conference was to increase the self-advocacy, transition, and leadership skills of

high school age students with learning and attention challenges. About 300 students with a

variety of abilities and disabilities from grades 9-12 attended the conference that took

place in Minneapolis in October, 1999. Arrangements to conduct the study were made

collaboratively between the University of Minnesota, the Minnesota Department of Children,

Families, and Learning, and Family Service Inc. of St. Paul.

Instrumentation and Procedures

Flyers posted in several locations at the

conference informed the students of the opportunity to participate anonymously in a

research project (see Figure 3). Interested students were interviewed during breaks

between conference sessions.

Figure 3. Invitation to

Participate in the Study

Calling All Students!!!

Will you help?

What helps you learn or take

tests?

It will take 5 minutes

to answer questions.

If you want to learn more

about this study, come to the interview table in the commons area during breaks or lunch

times.

You will receive a gift.

Thank You.

Individual students were invited to approach one of the ten

interviewers who were seated in different locations in a commons area. Interviewers

included researchers and graduate students from the National Center on Educational

Outcomes at the University of Minnesota and high school special education teachers and

consultants. The study and intent of the research were explained to each potential

participant, and permission was secured before the interview began. Following the

interview, each student received a small gift (transition planning guide, restaurant gift

certificate, and multi-colored highlighter) in appreciation of his or her participation.

Data were collected through a self-reporting interview. Questions

were asked orally, with no reading skills required to respond. Students were asked how

many times they had taken Minnesota’s Basic Standards Tests in Reading, Math and

Writing and whether they had passed each test. Next, the students were asked whether they

had used accommodations on any of the tests, and if so, which ones. A list of

accommodations across the categories used in Minnesota (presentation, response, time, or

setting) was available for students. Additional survey questions asked students to

identify accommodations they used in class and how they might continue to use these

accommodations in their future adult lives. (See Appendix A for survey protocol.) Students

were the only respondents. Responses were not verified by parents, teachers, or any other

adult chaperones, or matched to actual test results.

Results

Ninety-six high school students from school districts across

Minnesota agreed to participate in the study. Most the students were in grades 10 –

12 and ages 15 - 18. Figures 3 and 4 show the number of participants at each grade and age

level. Thirty-nine (41%) of the participants were girls and 57 (59%) were boys. All of the

participants received special education services; students were not asked to disclose

their primary disability. It was assumed that most of the conference attendees had

learning disabilities or mild cognitive impairments.

Participation and Performance

Seventy-five students, approximately three-fourths of the survey

respondents, indicated that they had taken at least one of Minnesota’s Basic

Standards Tests. Students who reported that they had not taken the tests (n = 12) or did

not know whether they had participated in testing (n = 9) were distributed fairly evenly

across grades (see Table 1). One student was too young to participate in testing and one

had recently moved to Minnesota from another state.

Table

1. Test Participation Status by Grade

Response

(n = 96) |

Grade

9 |

Grade

10 |

Grade

11 |

Grade

12+ |

Took at least one Basic Standards Test |

8 (80%) |

18 (82%) |

26 (75%) |

23 (80%) |

Did not take any Basic Standards Tests |

2 (20%) |

2 (9%) |

5 (14%) |

3 (10%) |

Do not know |

0 |

2 (9%) |

4 (11%) |

3 (10%) |

Total number of students |

19 |

22 |

35 |

29 |

Testing sessions are offered in the winter and summer, and

students can retake tests during each session until they pass. Table 2 shows the number of

times students reported taking each of the tests. Over 80% of the students interviewed

reported taking each test one or two times. Four students reported taking the Math test

four to six times and four students reported taking the Reading test four or five times.

About half of the students had not yet taken the Writing test, which is only offered to

students beginning in 10th grade.

Table 2. Number of

Students Reporting Taking BSTs Multiple Times

BST

Content |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Reading |

0 |

34 |

28 |

9 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

Math |

0 |

39 |

22 |

10 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

Writing |

37 |

28 |

9 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Note: These data are

from the 75 students who knew they had taken the BSTs at least once.

Fifty-six percent of the students who took the Basic Standards

Reading test at least once said that they had passed. A smaller number of students (45%)

reported passing the Math test, and 21% of the Writing test participants reported passing

(see Table 3).

Table 3. Passing

Rates Reported by Test Participants

Passed

Test? |

Reading |

Math |

Writing |

Yes |

56% |

45% |

55% |

No |

40% |

48% |

24% |

Don’t Know |

4% |

7% |

21% |

Note: These data are

based on the 75 students who reported taking the Reading and Math tests, and the 37

students who reported taking the Writing test.

Assessment Accommodations

About 75% of the students who participated in at least one Basic

Standards Test reported using accommodations on the tests. Only two assessment

participants said that they did not know whether they had used an accommodation. Table 4

shows that a greater percentage of students age 17 and older reported using accommodations

(84%) than students age 16 and younger (65%). Test accommodation use was fairly evenly

distributed among males and females. Forty-one students (55% of those tested) used one,

two, or three assessment accommodations on the Basic Standards Tests (25% used 0

accommodations, 23% used 1, 16% used 2, 16% used 3, 3% used 4, 8% used 5, and 9% used 6 or

more accommodations).

Table 4. Test

Accommodation Use by Age

Accommodations

Use |

14-15

Years |

16 Years |

17

Years |

18+

Years |

Used test accommodations |

70% |

59% |

86% |

82% |

Did not use test accommodations |

30% |

41% |

5% |

18% |

Don’t know |

0 |

0 |

9% |

0 |

Note: Percentages are

based on 20 14-15-yr-olds, 17 16-yr-olds, 21 17-yr-olds, and 17 18+-yr-olds.

Table 5 is a list of assessment accommodations students reported

using during the BSTs. The accommodations used by at least a quarter of these students

included extended time, testing in a separate room in a small group, having directions

repeated, and reviewing test directions in advance.

Table 5.

Percentages of Students Using Specific Assessment Accommodations

Accommodation |

%

Using |

Accommodation |

%

Using |

Extended time |

39% |

Tested different time of day |

8% |

Small group in separate room |

39% |

Large print test booklet |

5% |

Directions repeated |

32% |

Template to reduce visual field |

5% |

Directions in advance |

27% |

Special setting |

5% |

Math test read aloud |

16% |

Audio cassette and headphones for math |

4% |

Tested alone in separate room |

12% |

Directions amplified |

1% |

Directions written in test booklet |

9% |

Additional answer pages |

1% |

Short segment test booklet |

8% |

|

|

Note: Percentages are

based on 75 students.

An analysis of the test performance of students who reported using

accommodations showed that the same number of students who passed the Math test used

accommodations (N = 26) as the number who did not pass the Math test (N = 26). Of the 56

students who used accommodations on the Reading test, 30 passed and 23 did not pass.

Similarly, a greater number of students who passed the Writing test used accommodations (N

=17) than those who did not pass (N = 7) (see Table 6).

Table

6. Test Performance of Students Who Used Accommodations

Test |

Passed |

Not

Passed |

Don’t

Know |

Reading - Used accommodations |

30 |

23 |

3 |

Reading - No accommodations |

11 |

6 |

0 |

Reading - Don’t know |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Math - Used accommodations |

26 |

26 |

4 |

Math - No accommodations |

8 |

8 |

1 |

Math - Don’t know |

0 |

2 |

0 |

Writing - Used accommodations |

17 |

7 |

1 |

Writing - No accommodations |

3 |

2 |

6 |

Writing - Don’t know |

1 |

1 |

0 |

Classroom Accommodations

Several of the accommodations students used for assessments were

also used in daily classroom activities. As shown in Table 7, the most common of these

included extended time, working in a small group or in a separate room, having tests read

aloud, and having directions repeated.

Table

7. Students using assessment accommodations in the classroom

In addition to the assessment accommodations students reported

using in the classroom, additional classroom assessments were identified:

• Books on tape (3 students)

• Reduced reading (4 students)

• Larger screen on the computer (1

student)

• Noise buffer (1 student)

• Copy notes from students or copy lecture

notes (6 students)

• Use a notetaker (3 students)

• Oral test taking (1 student)

Students also identified a variety of teaching, learning, and

organizational strategies that they found useful in the classroom. Whether these are

viewed as accommodations specific to a student with disabilities or common learning

strategies may vary, depending on the student, setting, and situation:

• Work in a small group; cooperative

learning; study partners; peer tutors (15 students)

• Copy notes or directions from board or

overheads (14 students)

• Review and practice, “Go over

material until it sticks in your head” (9 students)

• Clear instructions, with examples (9

students)

• Take notes (7 students)

• Keep an assignment notebook (5 students)

• Set goals (6 students)

• Open book tests (5 students)

• Study guides (4 students)

• Sit in the front of the classroom, near

the teacher, or close to the board (3 students)

• Hands-on, experiential learning (3

students)

• Visual cues; movies (3 students)

• Use a calculator (2 students)

• Have an extra book to take home (2

students)

• Memory devices (1 student)

• Structured routine (1 student)

• “When they actually teach instead

of just giving us the book!” (1 student)

Several students talked about the usefulness of individual

instruction:

• Tutoring and individualized instruction

from teachers (10 students)

• Someone who can help me with reading;

with assignments; explaining homework and big words; with basic skills (6 students)

• Asking questions; asking for help when

needed (4 students)

Future Accommodations

When asked what accommodations students thought would be most

helpful for them in the future, about a third of them did not know or thought they

probably would not need accommodations in the future. Table 8 shows these responses by

grade and gender. Students in 11th grade

were the least sure about what they might need in the future. Female students less often

identified accommodations for the future than did male students.

Some students responded that they plan to use the same

accommodations in the future as they currently use on assessments and in the classroom

(see Table 9).

Students identified many additional accommodations and learning

strategies that they planned to use in their future adult lives. Accommodations identified

by two or more students were: Oral directions (n = 5), Written directions (n = 4), Review

often (n = 4), Take notes (n = 4), Hands-on learning and demonstration of knowledge (n =

3), Notetaker (n = 3), Someone to learn with, study buddy (n = 3), Simplify, repeat

directions (n = 2), Ask for things on board, overhead and handout sheets (n = 2), Use

study guides (n = 2), and Work alone (n = 2). Several

students also identified needs for help and support. For example, seven students

identified the need for another person to help (e.g., tutor, someone to help me if I have

trouble, one on one teaching, help with reading and spelling, teacher or counselor to go

to). Three students identified the need for greater explanation (e.g., of terms, of

expectations for assignments), and three identified the need for support (e.g., from

peers, friends).

Discussion

The results of this study showed that nearly all students

interviewed knew what tests we were talking about and seemed to understand the importance

of passing the tests. Most students also knew how many times they had taken each test and

whether they had passed. Further, about 75% of the students said that they had used

assessment accommodations; only two students did not know what accommodations were. Older

students were more likely to use assessment accommodations than younger students, and the

majority of students used three or fewer accommodations. Accommodations used most often

were extended time, testing in a separate room in a small group, having directions

repeated, and reviewing test directions in advance.

Students who said they used assessment accommodations, and

students who said they did not, reported passing the Math test at the same rates. Students

using accommodations for the Reading and Writing tests more often reported passing than

did students who did not use accommodations.

Several of the accommodations students used for assessments were

also used in daily classroom activities. These most commonly included extended time,

working in a small group or in a separate room, having tests read aloud, and having

directions repeated. Additional classroom accommodations students identified that would

not be conducive to assessment situations included books on tape, reduced amount of

reading, note-taker, and copy notes or directions from a chalkboard or overheads. One

student said, “sit by a smart person” and there were similar comments in favor

of “study buddies” and other cooperative learning strategies.

About two thirds of the students interviewed were able to identify

accommodations that would be helpful to them in their future adult lives. The other third

either did not know what would be helpful, or thought they probably would not need

accommodations in the future. Female students less often identified accommodations for the

future than did male students. Some students responded that they plan to use the same

accommodations in the future that they currently use on assessments and in the classroom. Students identified a variety of additional

accommodations and learning strategies that they planned to use in their future adult

lives, including: ask for directions to be written down or given orally; simplify and

repeat directions; demonstrate what is expected; get a note taker in college; ask for

notes to be written on a chalkboard, overhead, or handout sheets; tape record lectures and

instructions; and break tasks into smaller parts.

Recommendations for Research

The results of this study support the importance and need for

research that addresses the perceptions and opinions of students who indeed face the

greatest consequences as a result of participation in high stakes assessments. The

research that we conducted still must be considered preliminary. Despite the importance of

talking to students, our study was limited to the extent that the students did not

understand the questions or were unwilling to respond accurately. Because we conducted the

interviews in the fall, and tests were given the preceding winter and summer, it is also

possible that some students’ ability to remember accurately was reduced. Furthermore,

it is important to recognize that we simply asked students whether they had

“passed” the tests. In Minnesota, students with IEPs may be allowed to

“pass” at a lower score or with a modified test. We did not ask students whether

their tests had been modified. Because the interview was not a “test” to see

what students knew, but rather was designed to ask about perceptions and opinions, we did

not verify responses with teachers, parents, or actual test data. In addition, because of

the conference setting in which interviews were conducted, it is possible that some

interviewers gave more cues and examples than others. It is also possible that students

who approached interviewers as a group may have listed similar accommodations, possibly

because their friends gave them ideas, or because they wanted to “fit in” with

their friends’ responses.

Future research needs to address questions about participation and

accommodation decisions made by the IEP team, how those decisions are carried out in the

classroom, how students learn about and select assessment accommodations, how they

advocate for the use of accommodations in actual assessment situations, what students

think will improve test performance, and transferring the use of classroom and assessment

accommodations to plans for the transition to adult life.

Research should also be conducted to find out why some students

are not tested. In addition to counting the number of students tested, students themselves

should be asked about their participation and what motivates them to do their best.

Research should look at the use of test modifications, and what happens to those scores

both at the system and student levels.

Recommendations for Practice

It is important for students to understand the purpose of each

assessment they take and the use and consequences of the scores. Building knowledge of

strengths and limitations, self-advocacy skills, and strategies for learning in students

should be paramount for all students, regardless of whether they receive special education

services. Students need to be able to say, as one survey participant responded, “I

have somewhat of a disability.” Students need many opportunities to attain this

knowledge and skill throughout their school years.

Students listed several learning strategies in addition to

assessment accommodations. These strategies can be useful to a variety of students with

particular learning styles, regardless of the presence of an identified disability. For

example, having directions for an assignment written on a chalkboard or overhead is a

useful accommodation, but on a broader level, is a helpful instructional strategy for all

students. Some common teaching and learning strategies become specific accommodations in

situations where they are only allowed for students with disabilities. For example, in

some classrooms, any student can choose to sit near the front of the room, while in

others, students may be seated in a specific order (e.g., alphabetical) and a special

request then must be made for preferential seating. Students talked about the helpfulness

of open book tests. Again, this is an accommodation only to the extent that it is not

allowed for all students. Students also talked about learning strategies that played to

their strongest learning styles such as hands-on, experiential learning, demonstrations,

and visual cues. The fact that these came up during discussions about accommodations

suggests that regular classroom practice may not be very accommodating.

The purpose of using accommodations is to give students an

opportunity to show what they know and can do without the effects of a disability. This

purpose transcends assessments and classroom activities to each student’s post-school

education, career, and community life. When asked what accommodations students thought

would be most helpful for them in the future, about a third of them did not know, or

thought they probably would not need any. By the time students are juniors and seniors,

they should be well aware of what helps them learn and what helps level the playing field.

They should have several discussions about how to continue to use their knowledge and

skills as they make the transition to post secondary education or post-school careers.

This study powerfully demonstrates that valid and reliable

accommodations research can and must be conducted with students themselves – not only

as subjects, but also as important participants in interviews. Doing so will enlighten the

field not only about accommodations, but probably also about instruction. As one student

stated when asked what would be most helpful in a classroom setting: “When they

actually teach instead of just giving us the book!” While many educators have become

distracted from the gist of education reform by the flurry of assessments and discussions

of accommodations that surround the inclusion of students with disabilities, this student

has captured the essence of education reform in a simple sentence!

References

Agran, M., Snow, K., & Swaner, J. (1999). Teacher perceptions

of self-determination: Benefits, characteristics, strategies. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and

Developmental Disabilities, 34(3), 293-301.

Bersani, H. (1995, Summer). Leadership: Where we’ve been,

where we are, where we are going. IMPACT, 8(3),

2-3.

Bielinski, J., Ysseldyke, J. E., Bolt, S., Friedebach, M., &

Friedebach, J. (in press) Prevalence of accommodations for students with disabilities

participating in a statewide testing program. Diagnostique.

Carpenter, W. D. (1995). Become

your own expert: Self-advocacy curriculum for individuals with learning disabilities.

St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Education.

Elliott, J., Bielinski, J., Thurlow, M., DeVito, P., &

Hedlund, E. (1999). Accommodations and the

performance of all Students on Rhode Island’s performance assessment (Rhode

Island Report 1). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Education

Outcomes.

Field, S., & Hoffman, A. (1994). Development of a model for

self-determination. Career Development for

Exceptional Individuals, 17, 159-169.

Field, S., Hoffman, A., & Posch, M. (1997). Self-determination

during adolescence: A developmental perspective. Remedial

and Special Education, 18(5), 285-293.

Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Eaton, S. B., Hamlett, C., & Karns,

K. (2000). Supplementing teacher judgments about test accommodations with objective data

sources. School Psychology Review, 29 (1),

65-85.

Hollenbeck, K., Tindal, G., & Almond, P. (1998). Teachers

knowledge of accommodations as a validity issue in high-stakes testing. The Journal of Special Education, 32(3) 175-183.

Heumann, J. E., & Warlick, K .R. (2000, August 24). Questions

and answers about provisions in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Amendments

of 1997 related to students with disabilities and state and district-wide assessments

(Memorandum to State Directions of Special Education, OSEP 00-24). Washington, DC: Office

of Special Education Programs.

Kaiser, D., & Abell, M. (1997). Learning life management in

the classroom. Teaching Exceptional Children, 30(1),

70-75.

Lichtenstein, S. (1998). Characteristics of youth and young

adults. In R. Rusch & J. Chadsey (Eds.), Beyond

high school: Transition from school to work. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing

Company.

Liu, K., Anderson, M., Swierzbin, B., & Thurlow, M. (1999). Bilingual accommodations for limited English proficient

students on statewide reading tests. (Minnesota Report 20). University of Minnesota:

National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Martin, L. E., & Huber Marshall, L. (1997). Choice making:

Description of a model project. In M. Agran (Ed.), Student-directed

learning: Teaching self-determination skills. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

National Research Council (1998). High stakes testing for tracking, promotion, and

graduation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Schulte, A., Elliott, S. & Kratochowill, T. R. (2000).

Experimental analysis of the effects of testing accommodations on students’

standardized math test scores. Paper presented at the annual conference of the Chief

Council of State School Officers, Snowbird, Utah.

Thompson, S. J. & Thurlow, M. L. (1999). 1999 State special education outcomes: A report on

state activities at the end of the century. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of

Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Thompson, S. J., Thurlow, M. L., Quenemoen, R. F., Esler, A.,

& Whetstone, P. (2001). Addressing standards and

assessments on state IEP forms (Synthesis Report 38). Minneapolis, MN: University of

Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Thompson, S. J., Thurlow, M. L., & Spicuzza, R. (2000). 1999 report on the participation and performance of

students with disabilities on Minnesota’s Basic Standards Tests (Minnesota Report

29). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes.

Thurlow, M., House, A., Boys, C., Scott, D., & Ysseldyke, J.

(2000). State participation and accommodation

policies for students with disabilities: 1999 update (Synthesis Report 33).

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Education Outcomes.

Thurlow, M., Hurley, C., Spicuzza, R., and El Sawaf, H. (1996). A review of the literature on testing accommodations

for students with disabilities (Minnesota Report 9). Minneapolis, MN: University of

Minnesota, National Center on Education Outcomes.

Thurlow, M. L., Ysseldyke, J. E., & Silverstein, B. (1995). Testing accommodations for students with disabilities:

A review of the literature. Minneapolis: National Center on Educational Outcomes,

University of Minnesota.

Tindal, G., & Fuchs, L. (2000). A summary of research on test changes: An empirical

basis for defining accommodations. Lexington, KY: Mid-South Regional Resource Center.

Tindal, G., Helwig, R., & Hollenbeck, K. (1999). An update on

test accommodations: Perspectives of practice and policy. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 12, 11-20.

Trimble, S. (1998). Performance

trends and use of accommodations on a statewide assessment: Students with disabilities in

the KIRIS on-demand assessments from 1992-93 through 1995-96 (Maryland/Kentucky Report

3). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Education Outcomes.

Van Reusen, A. K., Deshler, D. D., & Schumaker, J. B. (1989).

Effects of a student participation strategy in facilitating the involvement of adolescents

with learning disabilities in the individualized educational program planning process. Learning Disabilities, 1(2), 23-24.

Wehmeyer, M. L., (1998). Student involvement in transition

planning and transition program implementation. In R. Rusch & J. Chadsey (Eds.), Beyond high school: Transition from school to work.

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

Greet the student.

Introduce

yourself as a research assistant with the University of Minnesota.

The key points to explain about the study

are:

·

All participants are anonymous.

Your name will not be used.

·

We want to identify what

accommodations are used in Minnesota high schools.

·

Ask if the student knows about

accommodations. If not sure, explain. An accommodation is a tool, strategy or adjustment

that helps a student to learn more or demonstrate better what he/she knows. For example,

assignment notebook, tape recording lectures, easier reading materials, paraphrasing what

is read, using a highlighted textbook, peer tutoring, additional time to complete tasks or

tests, private place to work free of distractions, etc.

·

We also want to think about the

accommodations that are offered during the Basic Standards Tests, graduation tests

starting in 8th grade.

·

Ask if the student knows about

the Basic Standards Test, graduation tests given in the 8th grade. If not,

explain.

·

Information will be used to

report to schools in Minnesota and other states to help teachers and students decide which

accommodations might be most helpful.

Do you have questions about what we want to

do and why?

Are you willing to assist by being

interviewed? (Record the response on the survey.)

This will take 5 minutes. If at any time you

want to stop the interview let me know.

Conduct the interview. Write on the back of

the interview form if needed. Use the accommodation cue card as needed for the last two

questions.

When the interview is completed, give the

student the “Students Rights; Students Responsibilities” planner page and offer

the student a gift of a subway coupon or highlighter pen. Mark the student’s

wristband with a “Smiley face” and have the student sign that they received

their gifts. Thank him or her for the contribution to research about accommodations to

help students show what they know.

Student Interview

Interviewer initials:

Are

you willing to take this survey? : o Yes o No

Gender: o Male o Female

Grade: o Freshman (9th) o Sophomore (10th) o Junior (11th) o Senior (12th)

Age: o 14 o 15

o 16 o 17 o 18

o 19 o 20 o 21

o 22

Taken

the Basic Standards Tests: o Yes o No o

Don’t know

How many times for Math: o 0 o

1 o 2

o 3 o 4 o 5

o 6 o 7

Passed the Math test: o Yes o

No o Don’t know

How many times for Reading: o 0 o

1 o 2

o 3 o 4 o 5

o 6 o 7

Passed the Reading: o Yes o

No o Don’t know

How many times for Writing: o 0 o

1 o 2

o 3

Passed the Writing: o Yes o

No o Don’t know

Did you use any accommodation on the

Basic Standards Tests?

o Yes o No o Don’t know

o What’s an accommodation

What accommodations did you use on the

Basic Standards Tests?

(Do not add to the list; mark all that

apply.)

directions in advance |

directions in ASL |

directions amplified |

directions repeated |

large print |

Braille version |

magnification |

templates to reduce visual

field/screens |

|

audio cassette and headphones for

Math |

Math test read |

additional answer pages |

extended time |

separate room, small group |

separate room, alone |

special setting |

different time of day |

word processor |

voice activated computer |

directions written in the test

booklet |

mark answers in the test booklet |

tape record answers |

tape record the Reading then listen |

tape record Writing ideas then

write |

scribe |

Braille writer |

Student is also LEP |

|

What accommodations help you to learn the most in classes? (Use

cues as needed to remind student of some possibilities then write the response.)

After graduation, what accommodations

do you think will help you to do your best at work or college?

Top of page |