Relationships Between a Statewide Language Proficiency Test and Academic

Achievement Assessments

LEP Projects Report 4

Published by the National Center on

Educational Outcomes

Prepared by Kentaro Kato,

Debra Albus, Kristin Liu, Kamil Guven, and Martha Thurlow

August 2004

Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and

distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as:

Kato, K., Albus, D., Liu, K., Guven, K., &

Thurlow, M. (2004). Relationships between a statewide language proficiency test and academic

achievement assessments (LEP Projects Report 4). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota,

National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide

Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/LEP4.html

Executive Summary

Minnesota is one of many states

that began development of an English proficiency test before federal

requirements were in place to do so. It had decided to put into place a test

that would provide the state with a better and more uniform gauge of how its

population of English language learners (ELLs) was doing in their acquisition of

academic English language skills. Minnesota chose to adapt its test, the Test of

Emerging Academic English (TEAE), from the Illinois Measure of Academic Growth

in English (IMAGE). The TEAE is designed to gauge the growth of emerging

academic English language skills across all grades, including three forms

spanning grades 3-4, 5-6, and 7-8. The 7-8 form is also designed for use with

students above grades 7-8.

This report focused on state ELL performance on the TEAE, in comparison to ELL

and fluent English student performance on Minnesota’s Comprehensive Assessment

(MCA) in reading in 3rd and 5th grade, and Minnesota’s Basic Skills Test (BST)

in reading in 8th grade. The TEAE is designed to measure the basic English

proficiency required for pursuing higher-level academic achievement, while the

MCA is designed to measure academic achievement toward the state standards. The

Basic Skills Test in reading measures the basic skills needed to be able to

graduate. Across these comparisons, our guiding research questions were to find

out what levels of the TEAE best predicts success on the MCA and BST, and

whether the state decision to count as proficient those ELLs who achieve at

level 4 on the TEAE has a sound base of support from an assessment perspective.

Study 1 addresses the questions related to the TEAE and the MCAs. Study 2

addresses the same questions for the TEAE and the BST.

Key Findings:

Study 1: TEAE and the MCA

-

ELLs in TEAE level 4 are likely

to do as well as native English speakers on the MCA, recognizing that there

is a range of performance among native speakers.

-

Although the specific

predictive relationship (i.e., what TEAE score corresponds to what MCA

score) can differ, the positive relationship between students’ performance

on the two tests is stable across years and grades.

-

For students with TEAE scores

below about 110, there is less ability to predict MCA scores.

-

Most students in TEAE level 3

fall into MCA levels 2A, 2B, or 3 and therefore although it is likely that

many within this group score as proficient (i.e., 2B or 3) others may not

(2A).

Study 2: TEAE and the BST.

-

TEAE scale scores had moderate

predictive power for BST performance. However, the predictability is not as

good as for the MCA.

-

To predict that a student would

be likely to pass the BST, he or she must score at least 260 (i.e., achieve

level 3) on the TEAE.

In conclusion, there might be

stronger relationships between the MCA and 3rd and 5th grade reading skills on

the TEAE because the academic language skills measured on the TEAE fit those

elementary grades better. Other factors besides potential discrepancies between

secondary grade level skills and basic academic language skills may also account

for differences in performance between the tests. These include differences in a

learner’s age upon entering Minnesota schools, differences based on student

familiarity or lack of familiarity with topical content and vocabulary for

individual passages encountered on the tests, and teachers’ own anecdotal

evidence which suggests that some students who take the TEAE do not take the

test seriously. Any combination of these and other individual student factors

could contribute to the TEAE not predicting success on the BST as well as on the

MCA.

Overview

Minnesota is one of many states that

began development of an English proficiency test before federal requirements

were in place to do so. It had decided to put into place a test that would

provide the state with a better and more uniform gauge of how its population of

English language learners (ELLs) was doing in their acquisition of academic

English language skills. Minnesota chose to adapt its test, the Test of Emerging

Academic English (TEAE), from the Illinois Measure of Academic Growth in English

(IMAGE). The TEAE, begun before Title III legislation required an annual growth

measure for English proficiency under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, is

now used to serve accountability purposes at federal and state levels, and is

the official measure to provide on-going identification of English language

learners in Minnesota for the purpose of state funding. This said, a student’s

proficient scores on the TEAE reading and writing tests do not prohibit him or

her from receiving on-going ESL/bilingual support as deemed feasible by local

districts.

The TEAE is designed to gauge the

growth of emerging academic English language skills across all grades, including

three forms spanning grades 3-4, 5-6, and 7-8. The 7-8 form is also designed for

use with students above grades 7-8. Gauging growth in academic English, and even

defining it, is a challenge for language acquisition specialists and assessment

specialists alike. The different viewpoints on what constitutes academic English

(Bailey, Butler, LaFramenta, & Ong, 2004; Chamot & O’Malley, 1994; Cummins,

1979; Scarcella, 2003; Solomon & Rhodes, 1995; Stevens, Butler, & Castellon-Wellington,

2000), makes the design, implementation, and interpretation of such a

proficiency test complex at best, especially when translating back the results

into what academic language skills a student truly needs for success across

content classrooms such as reading and mathematics.

This report focuses on state ELL

performance on the TEAE, in comparison to ELL and fluent English student

performance on Minnesota’s Comprehensive Assessment (MCA) in reading in 3rd and

5th grade, and Minnesota’s Basic Skills Test in reading in 8th grade (BST). The

TEAE is designed to measure the basic English proficiency required for pursuing

higher-level academic achievement, while the MCA is designed to measure academic

achievement toward the state standards. The Basic Skills Test in reading

measures the basic reading skills needed to be able to graduate. Across these

comparisons, our guiding research questions are to find out what levels of the

TEAE best predicts success on the MCA and BST, and whether the state decision to

count as proficient those ELLs who achieve at level 4 on the TEAE has a sound

base of support from an assessment perspective. Study 1 addresses the questions

related to the TEAE and the MCAs, Study 2 addresses the same questions for the

TEAE and the BST.

Study 1: TEAE and MCA

Method

In Study 1, we use the Minnesota

state test data of third and fifth graders in school year (SY) 2001-02 and

2002-03. Although the TEAE consists of reading and writing tests, we focus only

on the reading test and its relationship with the MCA reading test. Hereafter,

they are simply denoted by TEAE and MCA, respectively. The MCA data include test

scores of all students who participated in the state assessment. The TEAE data

consist of test scores of ELLs. The TEAE data originally contained 5,161 third

graders and 4,688 fifth graders in SY 2001-02, and 5,123 third graders and 4,683

fifth graders in SY 2002-03. The MCA data originally contained 61,922 third

graders and 64,408 fifth graders in SY 2001-02, and 60,018 third graders and

63,350 fifth graders in SY 2002-03. The data files for the same school year were

merged using the student ID as the key variable. At this step, students with

invalid or no student ID number were flagged so that they would not be used in

the subsequent analyses. The merged data were then screened to exclude students

who had any missing value on variables related to test scores (i.e., raw scores,

subscale scores, and scaled scores; if any of these is missing, then other

scores are not reliable even if they are recorded). Students who are recorded as

“not tested” on MCA were also excluded. The resulting sample sizes are shown in

the third column in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive

Statistics for TEAE and MCA Data

|

Year |

Grade |

N |

TEAE Reading

Scale Score |

MCA Reading

Scale Score |

r |

|

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

|

01-02 |

3 |

4361 |

186.22 |

35.26 |

14 |

383 |

1309.11 |

178.22 |

870 |

2050 |

.72 |

|

02-03 |

3 |

4541 |

181.94 |

39.31 |

5 |

408 |

1348.70 |

163.21 |

390 |

2060 |

.71 |

|

01-02 |

5 |

3983 |

227.94 |

44.05 |

25 |

377 |

1334.35 |

197.35 |

710 |

2060 |

.73 |

|

02-03 |

5 |

4238 |

216.60 |

39.85 |

9 |

425 |

1378.74 |

179.44 |

540 |

2220 |

.73 |

Note. N is sample size, SD

is standard deviation, and r is sample correlation between TEAE and MCA.

Next, we examined the relationship

between the two tests. English proficiency as measured by the TEAE is considered

to be prerequisite to minimal performance on the MCA. Thus, we expect that

performance on the two tests is positively related, but detailed analysis will

reveal more specifically the degree to which they are related. We analyzed the

data in three ways based on how the results of these tests may impact practice.

The first analysis examines the

relationship between the two tests at the scale score level. The scale scores of

the TEAE and the MCA represent English proficiency and academic achievement

toward the state standards, respectively. Every year performance on both tests

is converted from raw scores so that they have similar distributions across

years irrespective of changes in test items. Based on our research questions, we

inspected scatter plots of the MCA and TEAE, and then applied regression

analysis to examine the extent to which the MCA scale score is predicted by the

TEAE scale score.

The second analysis focused on the

relationship between the two tests by the proficiency or achievement level. The

MCA has five achievement levels, I, IIa, IIb, III, and IV, based on cutoff

points set on the scaled score. Students who are in level IIb or above are

counted as “achieved” for accountability purposes in Minnesota. The TEAE has

four levels to represent English language proficiency based on the scale score.

On both the MCA and the TEAE, each level is associated with a specific

description of progress toward the state standards (MCA) or English proficiency

(TEAE), and thus gives a brief and clearer interpretation of a test result.

Also, using such levels makes the results less sensitive to measurement errors

on scale scores. Examining the relationship between the two tests by the

proficiency or achievement level leads to relating a specific level of English

proficiency to a specific achievement level.

The third analysis is motivated by

the regulation that ELLs who have achieved the highest proficiency level (level

4 on reading and level 5 writing) on the TEAE are no longer eligible for funding

for LEP programs because they are regarded as having English proficiency

sufficient to access the academic content in the mainstream without further

language support. If results of the TEAE reflect this reasoning, then the

distribution of MCA scores of ELLs who are in the highest English proficiency

level are comparable to those of students who are not ELLs. In other words, the

means of the MCA score distributions of both groups of students should be almost

the same and the ranges of the distributions should substantially overlap.

Accordingly, the distribution of MCA scale scores for each of the TEAE

proficiency levels will be compared with the distribution of native English

speakers. Test scores of native English speakers were taken from the Minnesota

state test data as well, and those data were screened in the same manner as for

the TEAE.

Results

Descriptive Statistics for the Entire Sample

Descriptive statistics by grade and year were shown in Table 1. Within each

school year, fifth graders had higher mean scores on both the TEAE and MCA as

expected. Fifth graders had larger variability on the MCA than third graders in

both school years. Fifth graders had larger variability than third graders also

on the TEAE in 2001-02, while there is little difference in 2002-03.

Correlations between the TEAE and MCA are larger than .70 for all grades and

years. This indicates an overall stable, positive relationship between the TEAE

and MCA. Still, it is worthy of more detailed examination.

Analysis of Scale Scores

Scatter plots.

Scatter plots of MCA scale scores and TEAE scale scores by grade and year are

shown in Figures 1 through 4. These plots consistently indicate that the

majority of points are positively correlated. However, there is a group of

points that do not follow that major pattern in the region where TEAE scale

scores are less than a given point. For third graders in 2001-02, for example,

data points with TEAE scores less than about 100 seem to have almost no

correlation while the majority of data points are positively correlated. For

these "irregular" points, MCA scores looked highly unpredictable based on TEAE

scores. Thus, it is better to separate these points in order to investigate the

relationship that applies to the majority of students in the data set. The

question is, however, at what point we should separate regular and irregular

cases; there is no indicator variable that separates these two types of points

in the data files.

Figure 1. Scatter plot of MCA and TEAE

scale scores (2001-02, Grade 3)

Figure 2. Scatter plot of

MCA and TEAE scale scores (2002-03, Grade 3)

Figure 3. Scatter plot of

MCA and TEAE scale scores (2001-02, Grade 5)

Figure 4. Scatter plot of

MCA and TEAE scale scores (2002-03, Grade 5)

To estimate a cut off point for the

scale scores for each grade and year, the following simple linear regression

model is applied to the regular group of students (i.e., students with TEAE

scores greater than the cutoff point) to assess the predictability of the TEAE

on the MCA:

MCA = (Intercept) + b1

(TEAE) + e

Although there probably are multiple

ways to estimate the cutoff point, a change point analysis is used for this

purpose. It searches for the best cutoff point by fitting two different linear

regression models for regular and irregular groups, respectively.

It should be noted that the TEAE

scale scores show some discreteness in the score range above 300 (i.e., there

are big jumps between two adjacent possible scale scores) in the score range

above 300. This is more apparent for fifth graders, because more students marked

scores close to the maximum possible scale score. This discreteness results from

the scaling, which depends on the distribution of raw scores in each grade and

year.

Estimation of Cutoff Scores

Estimated cutoff scores are shown in

the third column in Table 2. The mean squared errors of MCA scores in the

irregular group estimated by the change point analysis were 167.97 and 163.53

for grade 3 (2001-02 and 2002-03, respectively), and 132.15 and 201.24 for grade

5 (2001-02 and 2002-03, respectively). These are almost the same as the

unconditional standard deviations listed in Table 1 except for fifth graders in

2001-02. Thus, we can conclude that MCA scores of students with TEAE scores less

than the cutoff points are not well predicted by the TEAE. Although these cutoff

points vary across years and grades, the unpredictability is likely to occur

when the TEAE score is less than about 110.

Table 2. Estimates of cutoff

scores and regression coefficients

|

Year |

Grade |

Cutoff |

N |

Intercept

(b0) |

Slope

(b1) |

R2 |

|

01-02 |

3 |

124.87 |

4217 |

501.46 |

4.29 |

.58 |

|

02-03 |

3 |

114.39 |

4417 |

739.63 |

3.31 |

.54 |

|

01-02 |

5 |

131.93 |

3953 |

561.85 |

3.38 |

.54 |

|

02-03 |

5 |

130.71 |

4161 |

593.82 |

3.60 |

.56 |

Note. Intercepts and slopes

are for the “regular” group of students with TEAE scores greater than the cutoff

point. N is the number of students included in the regular group, and R2

is the squared multiple correlation.

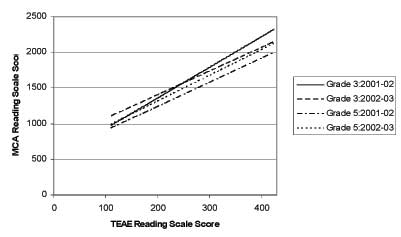

Regression Analysis for the Regular Group

In the fourth through seventh

columns in Table 2 are shown the number of students in the regular group,

estimated intercept, slope, and R squared for the regular group of students

(i.e., students with TEAE scores greater than the cutoff point). The slopes

range from 3.31 to 4.29, and the corresponding R2s range from

.54 to .58. These results indicate that more than 54% of variation of the MCA

scale score can be accounted for by the TEAE scale score for the regular group

of students. This is a strong positive relationship. The results also indicate,

however, that slopes vary to some extent across years and grades. The estimated

regression lines are plotted in Figure 5. As the slope estimates indicate, the

lines are almost parallel except for grade 3 in 2001-02, where the regression

line is slightly steeper than the others. Also, vertical locations of the lines

vary in the 200 range for the MCA score scale. The lines for grade 3 are higher

than those for grade 5 in Figure 5, but more longitudinal data would be required

to infer systematic effects of grade levels on regression lines. Overall,

although the specific predictive relationship (i.e., what TEAE score corresponds

to what MCA score) can differ, the positive relationship between the two tests

is stable across years and grades. Thus, we expect that increased English

proficiency is associated with progress toward the state academic standards.

Figure

5. Comparison of Estimated Regression Lines

Relationship by Proficiency or Achievement Level

Grade 3 TEAE Level and MCA Level Correspondence

Tables 3 and 4 show the number of

third graders cross-classified by TEAE proficiency levels and MCA achievement

levels in 2001-02 and 2002-03. Level 1 of the TEAE includes the “irregular”

group of students found in the analysis of scale scores.

Both 2001-02 and 2002-03 results

consistently indicated the following. First, students in TEAE level 1 are likely

(about 80%) to be in level 1 on the MCA, and thus to be counted as "not

proficient" for accountability purposes. This is a clear indication that basic

English proficiency is a prerequisite to achieving higher-level academic reading

skills. Second, students in TEAE level 4 are likely to achieve level 3 or 4 on

MCA, and thus to be counted as proficient for accountability purposes (the

result for 2001-02 may not be reliable due to the small sample size of 24 in

TEAE level 4). Thus, proficient English learners can do well on the MCA.

Finally, TEAE levels 2 and 3 seem to have no single corresponding level on the

MCA. Most students in TEAE level 2 fall in MCA level 1, 2A, or possibly 2B,

although they are unlikely to be proficient (2B) on the MCA. Also, most students

in TEAE level 3 fall into MCA levels 2A, 2B, or 3. They are likely to be

proficient on the MCA but there is still some possibility that they would not be

proficient.

Although there is no clear

one-to-one correspondence between the TEAE proficiency levels and the MCA

achievement levels, ELLs who are in TEAE level 3 or 4 are likely to be

proficient (i.e., scoring in level 2B or above) on the MCA.

Table 3. Correspondence

between TEAE Proficiency Levels and MCA Achievement Levels (2001-02, Grade 3)

|

|

|

|

MCA Reading

Achievement Level |

Total |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2A |

2B |

3 |

4 |

|

|

TEAE Reading

Proficiency Level |

1 |

Count |

1406 |

274 |

51 |

23 |

1 |

1755 |

|

|

Row% |

80.1 |

15.6 |

2.9 |

1.3 |

0.1 |

100.0 |

|

|

Column% |

73.1 |

23.2 |

7.7 |

4.5 |

1.1 |

40.2 |

|

|

Total% |

32.2 |

6.3 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

40.2 |

|

|

2 |

Count |

515 |

864 |

519 |

311 |

25 |

2234 |

|

|

|

Row% |

23.1 |

38.7 |

23.2 |

13.9 |

1.1 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

26.8 |

73.1 |

78.6 |

61.2 |

28.7 |

51.2 |

|

|

|

Total% |

11.8 |

19.8 |

11.9 |

7.1 |

0.6 |

51.2 |

|

|

3 |

Count |

3 |

43 |

89 |

167 |

46 |

348 |

|

|

|

Row% |

0.9 |

12.4 |

25.6 |

48.0 |

13.2 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

0.2 |

3.6 |

13.5 |

32.9 |

52.9 |

8.0 |

|

|

|

Total% |

0.1 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

3.8 |

1.1 |

8.0 |

|

|

4 |

Count |

0 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

15 |

24 |

|

|

|

Row% |

0.0 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

29.2 |

62.5 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

1.4 |

17.2 |

0.6 |

|

|

|

Total% |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

|

Total |

|

Count |

1924 |

1182 |

660 |

508 |

87 |

4361 |

|

|

|

Row% |

44.1 |

27.1 |

15.1 |

11.6 |

2.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Total% |

44.1 |

27.1 |

15.1 |

11.6 |

2.0 |

100.0 |

Note. Dark gray cells indicate that the row proportion is larger than 50% (i.e.,

more than 50% of MCA scores were at this level or these levels when the TEAE

score was the one in the row), and light gray cells indicate that the row

proportion is larger than 20% (i.e., more than 20% of MCA scores were at this

level or these levels when the TEAE score was the one in the row).

Table 4:

Correspondence between the TEAE Proficiency Levels and the MCA Achievement

Levels (2002-03, Grade 3)

|

|

|

|

MCA Reading

Achievement Level |

Total |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2A |

2B |

3 |

4 |

|

|

TEAE Reading

Proficiency Level |

1 |

Count |

323 |

58 |

21 |

4 |

0 |

406 |

|

|

Row% |

79.6 |

14.3 |

5.2 |

1.0 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Column% |

21.7 |

4.4 |

2.4 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

8.9 |

|

|

Total% |

7.1 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

8.9 |

|

|

2 |

Count |

1081 |

747 |

255 |

82 |

4 |

2169 |

|

|

|

Row% |

49.8 |

34.4 |

11.8 |

3.8 |

0.2 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

72.6 |

57.0 |

28.7 |

10.5 |

5.2 |

47.8 |

|

|

|

Total% |

23.8 |

16.5 |

5.6 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

47.8 |

|

|

3 |

Count |

84 |

495 |

561 |

523 |

29 |

1692 |

|

|

|

Row% |

5.0 |

29.3 |

33.2 |

30.9 |

1.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

5.6 |

37.8 |

63.2 |

67.2 |

37.7 |

37.3 |

|

|

|

Total% |

1.8 |

10.9 |

12.4 |

11.5 |

0.6 |

37.3 |

|

|

4 |

Count |

1 |

10 |

50 |

169 |

44 |

274 |

|

|

|

Row% |

0.4 |

3.6 |

18.2 |

61.7 |

16.1 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

0.1 |

0.8 |

5.6 |

21.7 |

57.1 |

6.0 |

|

|

|

Total% |

0.0 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

3.7 |

1.0 |

6.0 |

|

Total |

|

Count |

1489 |

1310 |

887 |

778 |

77 |

4541 |

|

|

|

Row% |

32.8 |

28.8 |

19.5 |

17.1 |

1.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Total% |

32.8 |

28.8 |

19.5 |

17.1 |

1.7 |

100.0 |

Note. Dark gray cells indicate that the row proportion is larger than 50% (i.e.,

more than 50% of MCA scores were at this level or these levels when the TEAE

score was the one in the row), and light gray cells indicate that the row

proportion is larger than 20% (i.e., more than 20% of MCA scores were at this

level or these levels when the TEAE score was the one in the row).

Grade 5 TEAE Level and MCA Level Correspondence

Results are shown in Tables 5 (for

the 2001-02 data) and 6 (for the 2002-03 data). Fifth graders showed results

similar to those of third graders for both academic years. There is a clearer

indication than for third graders that TEAE level 4 corresponds to MCA level 3.

Also, TEAE level 2 corresponds to MCA levels 1 or 2A, and TEAE level 3 to MCA

levels 2A, 2B, or 3. These observations are consistent in both school years.

Again, we can conclude that increased English proficiency of English learners is

associated with higher performance on accountability measures.

Table 5.

Correspondence between TEAE Proficiency Levels and MCA Achievement Levels

(2001-02, Grade 5)

|

|

|

|

MCA Reading

Achievement Level |

Total |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2A |

2B |

3 |

4 |

|

|

TEAE Reading

Proficiency Level |

1 |

Count |

362 |

24 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

391 |

|

|

Row% |

92.6 |

6.1 |

0.8 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

Column% |

24.5 |

2.0 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

9.8 |

|

|

Total% |

9.1 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

9.8 |

|

|

2 |

Count |

1002 |

672 |

126 |

99 |

6 |

1905 |

|

|

|

Row% |

52.6 |

35.3 |

6.6 |

5.2 |

0.3 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

67.8 |

56.2 |

27.1 |

14.2 |

4.1 |

47.8 |

|

|

|

Total% |

25.2 |

16.9 |

3.2 |

2.5 |

0.2 |

47.8 |

|

|

3 |

Count |

111 |

451 |

280 |

393 |

61 |

1296 |

|

|

|

Row% |

8.6 |

34.8 |

21.6 |

30.3 |

4.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

7.5 |

37.7 |

60.2 |

56.2 |

41.8 |

32.5 |

|

|

|

Total% |

2.8 |

11.3 |

7.0 |

9.9 |

1.5 |

32.5 |

|

|

4 |

Count |

2 |

49 |

56 |

205 |

79 |

391 |

|

|

|

Row% |

0.5 |

12.5 |

14.3 |

52.4 |

20.2 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

0.1 |

4.1 |

12.0 |

29.3 |

54.1 |

9.8 |

|

|

|

Total% |

0.1 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

5.1 |

2.0 |

9.8 |

|

Total |

|

Count |

1477 |

1196 |

465 |

699 |

146 |

3983 |

|

|

|

Row% |

37.1 |

30.0 |

11.7 |

17.5 |

3.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Total% |

37.1 |

30.0 |

11.7 |

17.5 |

3.7 |

100.0 |

Note. Dark gray cells indicate that the row proportion is larger than 50% (i.e.,

more than 50% of MCA scores were at this level or these levels when the TEAE

score was the one in the row), and light gray cells indicate that the row

proportion is larger than 20% (i.e., more than 20% of MCA scores were at this

level or these levels when the TEAE score was the one in the row).

Table 6.

Correspondence between TEAE Proficiency Levels and MCA Achievement Levels

(2002-03, Grade 5)

|

|

|

|

MCA Reading

Achievement Level |

Total |

|

|

|

|

1 |

2A |

2B |

3 |

4 |

|

|

TEAE Reading

Proficiency Level |

1 |

Count |

411 |

63 |

10 |

14 |

1 |

499 |

|

|

Row% |

82.4 |

12.6 |

2.0 |

2.8 |

0.2 |

100.0 |

|

|

Column% |

41.2 |

4.7 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

0.7 |

11.8 |

|

|

Total% |

9.7 |

1.5 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

11.8 |

|

|

2 |

Count |

458 |

531 |

108 |

55 |

0 |

1152 |

|

|

|

Row% |

39.8 |

46.1 |

9.4 |

4.8 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

45.9 |

39.4 |

13.2 |

5.9 |

0.0 |

27.2 |

|

|

|

Total% |

10.8 |

12.5 |

2.5 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

27.2 |

|

|

3 |

Count |

125 |

723 |

643 |

577 |

58 |

2126 |

|

|

|

Row% |

5.9 |

34.0 |

30.2 |

27.1 |

2.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

12.5 |

53.7 |

78.6 |

62.0 |

40.0 |

50.2 |

|

|

|

Total% |

2.9 |

17.1 |

15.2 |

13.6 |

1.4 |

50.2 |

|

|

4 |

Count |

3 |

30 |

57 |

285 |

86 |

461 |

|

|

|

Row% |

0.7 |

6.5 |

12.4 |

61.8 |

18.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

0.3 |

2.2 |

7.0 |

30.6 |

59.3 |

10.9 |

|

|

|

Total% |

0.1 |

0.7 |

1.3 |

6.7 |

2.0 |

10.9 |

|

Total |

|

Count |

997 |

1347 |

818 |

931 |

145 |

4238 |

|

|

|

Row% |

23.5 |

31.8 |

19.3 |

22.0 |

3.4 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Column% |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

|

Total% |

23.5 |

31.8 |

19.3 |

22.0 |

3.4 |

100.0 |

Note. Dark gray cells indicate that the row proportion is larger than 50% (i.e.,

more than 50% of MCA scores were at this level or these levels when the TEAE

score was the one in the row), and light gray cells indicate that the row

proportion is larger than 20% (i.e., more than 20% of MCA scores were at this

level or these levels when the TEAE score was the one in the row).

Comparability of MCA Scores

Grade 3 TEAE Level by MCA Scale Scores

Mean MCA scale scores by TEAE

proficiency level were compared with the mean MCA scale score of native English

speakers, and similar comparisons were made for dispersion of test scores (see

Table 7). Also, boxplots were drawn (see Figures 6 and 7). In these, the box

represents the middle 50% of the data, the top line represents the 75th

percentile and the bottom line represents the 25th percentile. A line

segment in the box indicates the median. The length of whiskers outside the box

is usually taken 1.5 times as large as the interquartile range, which is the

height of the box. All values outside the range of the whiskers are marked as

outliers and represented as dots in the plot. As in the comparison by the

proficiency or achievement levels, the irregular group of students was included

in the data. In the subsequent tables and figures, the group of native English

speakers is designated as "No TEAE."

Table 7. Mean MCA Scale Score by TEAE Proficiency Level (Grade 3)

|

|

2001-02 |

2002-03 |

|

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

|

TEAE Level 1 |

1176.83 |

134.23 |

1803 |

1169.46 |

140.41 |

429 |

|

TEAE Level 2 |

1374.23 |

129.56 |

2246 |

1275.52 |

129.68 |

2174 |

|

TEAE Level 3 |

1544.89 |

132.37 |

352 |

1448.44 |

103.66 |

1694 |

|

TEAE Level 4 |

1711.67 |

152.53 |

24 |

1575.96 |

106.47 |

275 |

|

No

TEAE |

1500.56 |

201.61 |

54263 |

1531.90 |

180.25 |

53556 |

Note. The group of native English speakers is designated as “No TEAE.”

Figure 6. Boxplots of Mean MCA Scale Scores by TEAE Proficiency Level (2001-02,

Grade 3)

Figure 7. Boxplots of

Mean MCA Scale Scores by TEAE Proficiency Level (2002-03, Grade 3)

In the 2001-02 school year, ELLs in

TEAE levels 3 and 4 had higher mean scores than native English speakers. The

result for TEAE level 4, however, is not reliable due to the small sample size;

the mean and standard deviation for that group are both too high. Dispersion of

scores is almost the same for all TEAE proficiency levels except for TEAE level

4, and they are much smaller than the dispersion for No TEAE. This is a natural

result because TEAE levels are correlated to the MCA scale scores.

Figure 6 shows that the ranges

indicated by whiskers (i.e., the lines extending from the box) for TEAE levels

2, 3, and 4 are completely within the whisker range of No TEAE (and the

interquartile ranges of these levels indicated by boxes also substantially

overlap that of No TEAE). Yet, the location of the distribution of TEAE level 2

is substantially lower compared with No TEAE. These results indicate that ELLs

in TEAE levels 3 or 4 can perform as well on the MCA as native English speakers.

In SY 2002-03, the pattern of score

distributions is somewhat different from that of SY 2001-02. The mean score in

2002-03 is lower than in 2001-02 at each TEAE proficiency level, whereas the

mean score of No TEAE in 2002-03 is higher than in 2001-02 (see Table 7). Also,

the score dispersion tends to be smaller as the TEAE level goes up, unlike in

2001-02. TEAE level 4 has a higher mean score than No TEAE as well as in

2001-02, but TEAE level 3 does not.

Figure 7 shows that the score

distributions of TEAE levels 3 and 4 are completely within the range of No TEAE,

but the distribution of TEAE level 3 is located relatively low to that of No

TEAE with little overlap of the interquartile range. Thus, the 2002-03 data

indicate that while ELLs in TEAE level 4 can perform as well on the MCA as

native English speakers, this may not be the case for those in TEAE level 3.

Grade 5 TEAE Level by MCA

Scale Scores

A summary of the MCA scale scores by

TEAE proficiency level is shown in Table 8, and boxplots are shown in Figures 8

and 9. Fifth graders in both 2001-02 and 2002-03 school years consistently show

a distributional pattern similar to third graders in 2001-02. In each school

year, the distribution of MCA scale scores of TEAE level 4 has almost the same

mean as the No TEAE group, and the range of the distribution is completely

within that of the No TEAE group. The range of TEAE level 3 is also within that

of No TEAE, but its mean is substantially lower than that of No TEAE in both

school years. Thus, for fifth graders, students in TEAE level 4 are comparable

to native English speakers.

Table 8. Mean MCA Scale Score by TEAE Proficiency Level (Grade 5)

|

|

2001-02 |

2002-03 |

|

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

|

TEAE Level 1 |

1092.51 |

170.12 |

438 |

1145.44 |

156.01 |

515 |

|

TEAE Level 2 |

1265.09 |

139.54 |

1934 |

1284.62 |

118.88 |

1157 |

|

TEAE Level 3 |

1445.88 |

144.26 |

1315 |

1440.35 |

125.87 |

2137 |

|

TEAE Level 4 |

1575.86 |

150.46 |

399 |

1593.39 |

134.78 |

463 |

|

No

TEAE |

1567.84 |

211.23 |

57147 |

1580.66 |

196.60 |

57104 |

Figure 8. Boxplots of

Mean MCA Scale Scores by TEAE Proficiency Level (2001-02, Grade 5)

Figure 9. Boxplots of

Mean MCA Scale Scores by TEAE Proficiency Level (2002-03, Grade 5)

Study 2: TEAE and BST

Method

The data used in these analyses,

like those used for the MCA analyses, are from 2001-02 and 2002-03. With state

eighth grade performance, we again focus on the TEAE reading test in comparison

to the BST reading test (hereafter, referred to as TEAE and BST). The TEAE data

originally contained 4,019 eighth graders in SY 2001-02, and 3,865 in SY

2002-03. The BST data originally contained 61,922 eighth graders, 66,769 in SY

2001-02, and 66,975 in SY 2002-03. The data were screened in the same manner as

for the TEAE-MCA analysis: excluding students who (a) had any missing value on

variables related to test scores, (b) were recorded as “not tested” on the BST,

and (c) had the minimum possible score on the TEAE. The resulting sample sizes

are shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Descriptive

Statistics for TEAE-BST Data

|

Year |

Grade |

N |

TEAE Reading

Scale Score |

BST Reading

Scale Score |

r |

|

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

|

01-02 |

8 |

3315 |

247.77 |

42.19 |

59 |

417 |

589.89 |

42.62 |

434 |

750 |

.71 |

|

02-03 |

8 |

3331 |

243.87 |

39.00 |

28 |

437 |

585.50 |

44.04 |

456 |

750 |

.66 |

Note. N is the sample size, SD is the standard deviation, and r is

the sample correlation between TEAE and BST.

The purpose of this analysis was to

examine how basic English proficiency measured by the TEAE relates to (a)

acquisition of basic academic reading skills, and (b) the reading skills needed

to pass the BST as needed for graduation. We therefore analyzed the data in two

ways.

The first analysis examined how

English proficiency affects acquiring basic academic skills. This was done by

examining the relationship of the TEAE and BST at the scale score level. We used

scatterplots and regression analysis to examine the extent to which the BST

scale score is predicted by the TEAE scale score.

The second analysis focused on how

English proficiency affects passing rates. The criterion for graduation is a BST

scale score greater than 600. In this analysis, the TEAE scale score is used as

a predictor of the passing rate. Since the criterion variable for each student

is binary (i.e., passed or failed), the logistic regression analysis is employed

to predict passing rates. Passing rates are also compared across proficiency

levels of the TEAE.

Results

Descriptive Statistics for the Entire Sample

Means and standard deviations of

test scores are very similar in both academic years. The correlations between

the TEAE and BST were .71 and .66 in SY 2001-02 and SY 2002-03, respectively.

They are slightly smaller than the correlations between the MCA and TEAE. Also,

the correlation in 2002-03 is smaller than that in 2001-02.

Analysis of Scale Scores

Scatter plots.

BST scale scores were plotted against TEAE scale scores for each school year.

These plots, however, showed that the BST scale score increases exponentially

rather than linearly as the TEAE scale score increases. This seemed to be a

result of scaling of the BST scale score. The distribution of the BST raw scores

peaked close to the maximum possible score. Then, on the resulting scale, raw

score points close to the maximum were stretched out, that is, intervals between

these scale scores were much longer than those between scale scores from lower

raw scores. In order to apply linear regression models, the BST scale score was

log-transformed so that the relationship between the BST and TEAE was more

linear. The resulting scatter plots for 2001-02 and 2002-03 school years are

shown in Figures 10 and 11.

Figures 10 and 11 show that the TEAE

scale score and the log-transformed BST scale score is positively related, and

the relationship is almost linear. However, we do observe a small number of data

points that lie outside the central region in which most of the data points

concentrate. These observations will negatively affect the predictability of the

BST scale score. Unlike the MCA, these points are distributed across almost the

entire range of the TEAE scale score. Also, higher TEAE or BST scores show

discreteness due to the scaling, although the discreteness of the BST has been

weakened by the log-transformation. With the information currently at hand, we

have no basis for removing these data points. Thus, all of these data points

were used for the regression analysis.

Regression Analysis

The following linear regression

model, was applied by school years in order to assess the predictability of the

BST:

log(BST) = (Intercept) + b1(TEAE)

+ e

The results are shown in Table 10.

The estimated regression lines are almost the same, but R2 for

2002-03 is smaller than for 2001-02. Also, these R2s are

smaller than those for the MCA. Thus, the BST scale score can be predicted by

the TEAE scale score to a moderate degree, because English proficiency affects

acquiring basic academic skills in reading. However, the predictability is not

as good as for the MCA.

The relationship between the BST and

TEAE seems to be stable across years, as shown in Figure 12 in which the

estimated regression curves from both school years are plotted (the log-BST

scale score is transformed back to the original scale score). TEAE scores that

give the predicted value of the BST score of 600 (i.e., 600 corresponds to 6.4

on log scale in Figures 10 and 11) are 263.81 and 265.18 for 2001-02 and 2002-03

school years, respectively. Thus, students with TEAE scores greater than these

values are expected to have BST scores greater than 600.

Table 10.

Estimates of Regression Coefficients

|

Year |

Grade |

Intercept(b0) |

Slope(b1) |

R2 |

|

01-02 |

8 |

6.07 |

.0012 |

.52 |

|

02-03 |

8 |

6.06 |

.0013 |

.45 |

Note. R2 is the

squared multiple correlation.

Figure 10. Scatter

plot of BST scale scores (log-transformed) and TEAE scale scores (2001-02, Grade

8)

Figure 11.

Scatterplot of BST Scale Scores (log-transformed) and TEAE Scale Scores

(2002-03, Grade 8)

Figure 12. Comparison

of Estimated Regression Curves

Predicting Passing Rates

Logistic Regression Analysis

The following logistic regression

model was applied by school years in order to assess the predictability of the

BST passing rate:

logit[Pr(Passing on BST)] =

(Intercept) + b1(TEAE) + e

The term logit(p) denotes the

logarithm of odds in terms of probability p, that is, logit(p) =

log[p / (1 - p)]. The logistic regression model assumes that the

logit of the target proportion (i.e., the passing rate in this context) is

linearly related to the predictor (i.e., TEAE scale score). The results are

shown in Table 11. Because the slopes are positive, the passing rate increases

as the TEAE scale score increases. However, Cox-Snell R2s are

small (.33 and .29, respectively), so the predictability is low. In fact,

correct classification rates are not very high (78.0% and 75.1%, respectively).

These rates were computed as follows. First, a predicted passing rate is

computed using the estimated regression curve and the TEAE score for each

student. Next, each student was classified as "passed" if the predicted passing

rate is greater than .5 and as "failed" otherwise. The correct classification

rate is then computed as the proportion of students whose predicted and actual

pass/fail values are the same. Thus, predicting passing or failing on the BST

using the TEAE is more difficult than simply predicting BST scores.

The median effective levels, which

give the TEAE scores the predicted passing rate of .50, are 263.43 and 260.71.

Thus, in order to predict that a student would likely pass the BST, they must

score at least 260 on the TEAE.

Table 11. Estimates of

Regression Coefficients

|

Year |

Grade |

Intercept

(b0) |

Slope

(b1) |

R2 |

|

01-02 |

8 |

-12.25 |

.047 |

.33 |

|

02-03 |

8 |

-11.26 |

.043 |

.29 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Note. R2 is

Cox-Snell squared multiple correlation, which is an analogue of ordinary R2

in linear regression.

Although the relationship in terms of the passing rate is

relatively weak, it is considered to be stable across years. In Figure 13, the

estimated regression curves are plotted. They are almost identical.

Figure 13. Comparison

of Estimated Regression Curves

Passing Rates by Proficiency Level

Passing rates were also compared by

TEAE proficiency level. The passing rates are shown in Table 12, and

corresponding graphs displayed in Figures 14 and 15 for each school year. Table

12 indicates that in both school years, (a) passing rates in levels 1 and 2 are

very low (less than 10%), and (b) only level 4 had reasonably high passing

rates. Level 1 has slightly higher passing rates than level 2, but the reason is

not clear. Although the results are similar across years, passing rates in

2002-03 were slightly lower than in 2001-02 for all levels as well as overall.

These results indicate that in order to pass on the BST, students must be at

least in level 3 on the TEAE. But we reiterate that only students in level 4 had

reasonably high passing grades.

Table 12. Estimates of

Regression Coefficients

|

Year |

Grade |

TEAE Reading Proficiency Level |

Overall |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

2001-02 |

8 |

.066 |

.057 |

0.44 |

0.87 |

0.39 |

|

2002-03 |

8 |

.063 |

.046 |

0.38 |

0.80 |

0.37 |

Figure 14. Passing

rates by TEAE Proficiency Level (2001-02)

Note. The numbers

indicated in the graphs are the number of students.

Figure 15. Passing

Rates by TEAE Proficiency Level (2002-03)

Note. The numbers

indicated in the graphs are the number of students.

Discussion

The Study 1 results show that

although the specific predictive relationship (i.e., what TEAE score corresponds

to what MCA score) can differ, the positive relationship between the two tests

is stable across years and grades. Also, the results suggest that ELLs in TEAE

level 4 would do as well as native English speakers on the MCA. This finding

indicates that those students in level 4 are more able to excel in academic

achievement assessments in reading toward the state standards, and thus supports

the state’s decision to count English learners who have achieved the highest

proficiency level on the TEAE as fluent English proficient. However, the

different distributional pattern for third graders in 2001-02 implies that there

may be some fluctuations across year and grade.

For students with scores below the

cut point (110), there is less ability to predict MCA scores. Most students in

TEAE level 3 fall into MCA levels 2A, 2B, or 3 and therefore although it is

likely that many within this group score as proficient (i.e., 2B or 3) others

may not (2A). Although there is no clear one-to-one correspondence between the

TEAE proficiency levels and the MCA achievement levels, ELLs who are in TEAE

level 3 or 4 are likely to be proficient (i.e., scoring in level 2B or above) on

the MCA.

Results of Study 2 showed that TEAE

scale scores had moderate predictive power for BST performance. However, the

predictability is not as good as for the MCA. In order to predict that a student

would likely pass the BST, he or she must score at least 260 (i.e., achieve

level 3) on the TEAE. Thus, we see the effect of acquiring basic English

proficiency on acquiring basic academic skills in reading.

In conclusion, there might be

stronger relationships between the MCA and 3rd and 5th grade reading skills on

the TEAE because the academic language skills measured on the TEAE addressed the

skills taught in those elementary grades. Yet, students in the middle and high

school grades face increasing demands in terms of academic language. This

suggests that the TEAE, although providing a basic picture of academic language

skills, may not detect as well the academic skills of students at the higher

grades. However, this requires further research.

Other factors besides potential

discrepancies between secondary grade level skills and basic academic language

skills may also account for differences in performance between the tests. These

include differences in a learner’s age upon entering Minnesota schools. It is

possible that the relationship of the tests may differ for learners who started

schooling in America in 10th grade as opposed to learners who had

been in the educational system from 4th grade. Also, the relationship

between tests may be affected by individual student performance based on

familiarity or lack of familiarity with topical content and vocabulary for

individual passages encountered on the tests. Although the match varies between

content tested and background knowledge for every reading test, it still has the

potential to affect student results. For example, a student may be familiar with

the language and content on the TEAE reading test, but may lack familiarity with

language or content needed to successfully apply similar skills to a BST reading

passage, or vice versa. Finally, Minnesota teachers’ own anecdotal evidence

suggests that some students who take the TEAE do not really try, or do not take

the test seriously. Any combination of these and other individual student

factors could contribute to the TEAE not predicting success on the BST as well

as on the MCA.

References

Bailey, A., Butler, F., LaFramenta,

C., & Ong, C. (2004). Towards the characterization of academic language in

upper elementary science classrooms (CSE Report 621). Los Angeles, CA:

University of California, National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards,

and Student Testing.

Chamot, A. U., & O'Malley, J. M.

(1994). The CALLA handbook: How to implement the Cognitive Academic Language

Learning Approach. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Cummins, J. (1979)

Cognitive/academic language proficiency, linguistic interdependence, the optimum

age question and some other matters. Working Papers on Bilingualism, No. 19,

121-129.

Scarcella, R. (2003). Academic

English: A conceptual framework. Irvine, CA: University of California,

Linguistic Minority Research Institute.

Solomon, J., & Rhodes, N. (1995).

Conceptualizing academic language (Research Rep. No. 15). Santa Cruz:

University of California, National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and

Second Language Learning.

Stevens, R. A., Butler, F. A., &

Castellon-Wellington, M. (2000). Academic language and content assessment:

Measuring the progress of English language learners. Los Angeles, CA:

University of California, National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards,

and Student Testing.

Top of page |