Overview

There is a long history, supported by requirements in federal education legislation, of students with disabilities receiving assessment accommodations. Students’ Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) explicitly reference needed accommodations to address specific student needs. Providing assessment accommodations for English learners (ELs) is a newer requirement for states. For students who are ELs, test accommodations are a way to make sure that their test scores more accurately reflect what they know about the content while minimizing the barriers created by their developing English proficiency. These accommodations may provide support in five different aspects of testing. First, they may address the presentation of test content (i.e., presentation accommodations). Second, they may address the ways students respond to test content (response accommodations). Third, they may address the equipment or materials students use to complete the test (equipment or materials accommodations). Fourth, they may address the timing of the test administration (timing/scheduling accommodations). Fifth, they may address changes to the testing environment (setting accommodations) (Kieffer, Lesaux, Rivera, & Francis, 2009; Shyyan, Thurlow, Christensen, Lazarus, Paul, & Touchette, 2016).

In 2008, Willner, Rivera, and Acosta, found that state assessment policies allowed a wide variety of accommodations for ELs on state English language arts and mathematics assessments, but many of the accommodations allowed did not support students’ linguistic needs. Only 40 of the 104 allowable accommodations for ELs (38.5%) provided direct linguistic support (e.g., simplified English, translation of directions) or indirect linguistic support (e.g., extra time) to students who were developing English proficiency. The remaining 64 accommodations available to ELs (61.5%) did not provide linguistic support (e.g., large print, small group test administration). The authors recommended that states increase efforts to choose accommodations supporting ELs’ language development needs.

At the time of Willner et al.’s review (2008), state policies allowed many accommodations for which there was little or no supporting research on their effectiveness with ELs. This concern still exists a decade later. In a literature review covering the years 1997-2010, Kieffer, Rivera, and Francis (2012) reviewed research on nine accommodations used by English learners (see Table 1). They found that because published research studies often examined multiple accommodations at the same time or described multiple research activities, the best way to gauge the frequency with which researchers studied an accommodation was to count the number of research samples associated with an accommodation.

Table 1: Effectiveness and Use of Accommodations Reviewed by Kieffer et al. (2012)

| Accommodation |

Number of

Samplesa |

Type of Linguistic

Supportb |

Significant

Effectc |

Frequently

Allowed

by Statesd |

| Simplified English |

24 |

Direct |

Small average |

No |

English dictionary or

glossary |

18 |

Direct |

Small average |

No |

Bilingual dictionary

(glossary) |

6 |

Direct |

No |

Yes |

| Native language test |

5 |

Direct |

No |

No |

| Bilingual test booklets |

5 |

Direct |

No |

No |

| Extended time |

3 |

Indirect |

Small average |

Yes |

| Reading items aloud |

2 |

Direct |

No |

Yes |

Bilingual questions and read

aloud in native

language |

1 |

Direct |

No |

No |

Small group test

administration |

1 |

None |

No |

Not addressed |

a Studies sometimes addressed multiple accommodations and had more than one student sample.

b Willner et al. (2008) characterized the type of linguistic support accommodations provide as direct, indirect, or none.

c Kieffer et al. (2012) characterized the significance of the effect of accommodations.

d Willner et al. (2008) characterized whether accommodations were frequently allowed by states. “Yes” represents accommodations allowed by half, or more, of states. “No” represents accommodations allowed by less than half of states. “Not addressed” indicates an accommodation not mentioned in Willner et al.’s study.

Table 1 shows that the most frequently studied accommodations during that 13-year time period, namely simplified English (24 study samples), English dictionaries or glossaries (18 study samples), bilingual dictionaries (6 study samples), native language tests (i.e., translated tests; 5 study samples), and bilingual test booklets (5 study samples) were not necessarily the most frequently allowed in state policies. Studies addressed simplified English most often, but state policies did not frequently allow this accommodation. In contrast, one of the accommodations with the least amount of research in Kieffer et al.’s review—reading test items aloud—is an accommodation that is becoming much more widely allowed by states for a variety of student groups (Thurlow, Quenemoen, & Lazarus, 2011; Willner et al., 2008).

Even in cases where there is research on an accommodation, the results of the studies are not always significant. For example, as shown in Table 1, states have commonly allowed bilingual dictionaries and reading test items aloud, but Kieffer et al. (2012) found no significant effect of these accommodations for ELs in the research they reviewed.

The lack of findings about the effectiveness of native language accommodations in studies reviewed by Kieffer et al. (2012) raises questions about the appropriateness of accommodations like bilingual dictionaries, native language tests, and bilingual test booklets for the students participating in the studies. Native language assessment accommodations are most effective when students have received content instruction in that language (Kieffer et al., 2009). The same question of appropriateness and necessary prerequisite skills applies to other accommodations as well. A student’s English proficiency level also may play a role in the effectiveness of certain accommodations (Albus, Thurlow, Liu, & Bielinski, 2005; Kopriva, Emick, Hipolito-Delgado, & Cameron, 2007; Pennock-Roman & Rivera, 2007; Wolf et al., 2008)

There are concerns that ELs may frequently be using assessment accommodations with no research base (Abedi & Ewers, 2013; Willner et al., 2008) that do not match an individual student’s characteristics and needs, or that do not support the student’s developing English skills (Willner et al., 2008). Using ineffective or inappropriate testing accommodations may be just as harmful to an EL as using no accommodation at all (Kopriva et al., 2007). In order to choose the most beneficial accommodations for an individual EL, educators need access to the most up-to-date research findings on the effectiveness of those accommodations for this population of students. Abedi and Ewers (2013) evaluated the research literature and gave guidance on those accommodations with the greatest evidence of validity and effectiveness at providing access to test content for ELs. This information is invaluable to educators involved in accommodations decision making for ELs. Kieffer et al. (2009, 2012), and Abedi and Ewers (2013), highlighted a need for additional research in several key areas. First, there is a need for more research examining the two most frequently studied accommodations: simplified English and English dictionary use (Abedi & Ewers, 2013; Kieffer et al., 2009, 2012). More studies would enhance the findings of existing meta-analyses documenting the effectiveness of these two accommodations.

Second, more studies are needed on accommodations that have not been widely studied (Kieffer et al., 2009). This new research might address both accommodations commonly allowed for state assessments and innovative accommodations that are not yet widely used. Abedi and Ewers (2013) indicated a high level of need for research on the use of commercial English dictionaries, bilingual dictionaries and glossaries, and reading tests aloud. Existing studies addressing ways to improve assessment design for ELs may hold particular promise for suggesting new and innovative accommodations to study (Kieffer et al., 2009).

Third, there is a need for more studies that investigate the effectiveness of particular accommodations for students with varying characteristics such as English proficiency or native language proficiency levels (Kieffer et al., 2009). To date, the majority of research that has examined students’ native language backgrounds has addressed Spanish speakers (Kieffer et al., 2012). Research documenting the effectiveness of accommodations for ELs from other language groups is in high demand. In addition, studies of the effectiveness of particular accommodations for students in different instructional settings are also important to conduct. Fourth, there is a need for additional research on ways to choose appropriate accommodations for ELs with different characteristics (Kieffer et al., 2009).

The purpose of this report is to review the published EL accommodations literature from 2010 to 2018 with particular attention to identifying any studies that: (a) provide new information on frequently studied accommodations such as simplified English or the use of an English dictionary or glossary, (b) address innovative accommodation types, or (c) examine the role of student characteristics such as English proficiency or native language background in the effectiveness of accommodations. This time span allows us to identify research conducted since Sato, Rabinowitz, Gallagher, and Huang’s 2010 study of linguistic simplification, which met What Works Clearinghouse Standards. We selected this time period because it was during this period, starting in 2010, that states were seriously working toward providing their assessments via technology rather than using paper and pencil tests. This transition to computer-based assessments resulted in significant shifts in approaches to providing accommodations and other accessibility features (Kopriva, Thurlow, Perie, Lazarus, & Clark, 2016). Finally, given educators’ increasing need for evidence-based research on appropriate accommodations, this review also addresses the influence of the study designs employed on the strength of the research findings.

Table of Contents

Review Process

To find articles published from 2010-2018 that addressed the effect of an accommodation on EL test performance, we used several search terms. These included: English learner, ELs, limited English proficiency, accessibility features, accommodation, test, state test, assessment, linguistic modification, test accommodations, translation, dictionary, glossary, simplified English, and K-12.

Literature Search Strategy

We used several search strategies to locate eligible studies published between 2010 and 2018. First, we searched two large online databases. The primary database was the University of Minnesota’s Libraries Database, MNCat Discovery. This database aggregates articles from top research databases such as ERIC, PsycINFO, SAGE Premier, ProQuest, and Academic Search Premier. We then conducted similar searches in Google Scholar to confirm the results.

Second, we used several internal resources housed at the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO). NCEO’s internal resources were hand-searched for pertinent articles. This included a search through a personal Mendeley list and NCEO’s Accommodations Bibliography (available at https://nceo.info/Resources/bibliographies/accommodations/bibliography) that houses a collection of over 300 empirical studies on the effects of various testing accommodations for students with disabilities. To focus specifically on ELs, we used the search phrase English Language. Further, as an additional way to confirm findings from the initial broad search, we conducted similar searches on testing company websites (e.g., Educational Testing Service [ETS], Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers [PARCC], WIDA, College Board) and on the websites of organizations that conduct assessment research on ELs (e.g., WestEd, Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing [CRESST]). Third, we reviewed reference lists in the eligible studies located during the initial searches. We added any articles discovered during these website and reference list searches to our list of eligible studies. Our search efforts led us to 49 possible articles to be included in the review. We then screened each article according to a set of inclusion criteria.

Coding and Screening Procedure

We reviewed each of the 49 articles for its adherence to the following criteria: (a) published in English; (b) addressed a K-12 educational context in the United States; (c) studied ELs, ELs with disabilities, or bilingual students; (d) examined testing accommodations as opposed to instructional accommodations; and (e) contained empirical research (either qualitative or quantitative). We excluded meta-analyses because they tended to synthesize the results of multiple studies that may not have fit our inclusion criteria. We also excluded general articles of accommodation effects that did not list the accommodations studied. In the event that more than one article by the same author met the inclusion criteria, we checked the articles for similarities and potential overlap. If the articles seemed to contain identical data, we included the earliest peer reviewed article. When possible, we prioritized studies containing original data. However, there were cases where this was not possible. For example, the original source of the data described by Solano-Flores, Wang, Kachchaf, Soltero-Gonzalez, and Nguyen-Le (2014) was unpublished, so we selected the earliest peer reviewed source instead. This analysis focuses on 11 published research studies that met these criteria.

These 11 studies were then coded for more specific information, including: (a) purpose of research, (b) assessment type, (c) content area assessed, (d) accommodation type, (e) research sample and participant characteristics, (f) research design type, (g) findings, and (h) author-identified limitations. We discuss each of these coding categories in more detail in the Results section.

Table of Contents

Results

The search process produced 11 research studies published between 2010 and 2018 that we ultimately selected for this analysis. Seven of the studies were published in journals, one in a report, and three were dissertations. The 11 studies are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Studies Included and Accommodations Addressed

| Study |

Accommodations Addressed |

| Alt, Arizmendi, Beal, & Hurtado (2013) |

Translation |

| Beckham (2015) |

Spanish-enhanced administration of a test in English |

Cawthon, Leppo, Carr, & Kopriva

(2013) |

Multiple adaptations to lesson language load of items

(e.g., visuals, graphics, formatting, linguistic

modification) |

| Cohen, Tracy, & Cohen (2017) |

Pop-up English glossary |

| Deysson (2013) |

Linguistic modification and Spanish translation |

| Kuti (2011) |

Analysis of existing state assessment data set to

determine

effectiveness of all accommodations used |

| Robinson (2010) |

Translation |

| Roohr & Sireci (2017) |

Pop-up glossary and sticker paraphrasing tool |

Solano-Flores, Wang, Kachchaf,

Soltero-Gonzalex, & Nguyen-Le (2014) |

Illustrations |

| Wolf, Kim, & Kao (2012) |

Glossary and read aloud |

Young, King, Hauck, Ginsburgh, Kotloff,

Cabrera, & Cavalie (2014) |

Linguistic modification |

Purpose of the Research

The 11 reviewed studies frequently described more than one research purpose. The primary purpose was to determine the effect of the use of an accommodation on the performance of ELs (see Table 3; for details on each study see Appendix A). Ten of the 11 studies indicated this was a purpose (Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Cawthon et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Deysson, 2013; Kuti, 2011, Robinson, 2010; Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014). The second most common purpose of the reviewed research was to study the perception of students or educators about accommodations use, which was listed by three studies (Beckham, 2015; Kuti, 2011; Wolf et al., 2012). Two studies examined patterns of student accommodations use (Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Wolf et al., 2012). Finally, one study investigated the effects of accommodations on test score validity (Cohen et al., 2017). Four studies listed multiple purposes (Beckham, 2015; Cohen et al., 2017; Kuti, 2011; Wolf et al., 2012).

Table 3. Purpose of Reviewed Research

| Research Purpose |

Number of Studiesa |

Determine the effect of the use of accommodation

on performance of ELs |

10 |

| Study perception of accommodation use |

3 |

| Examine patterns of student accommodations use |

2 |

| Investigate the effects of accommodations on test score validity |

1 |

a Four studies had more than one research purpose.

Type of Assessment

The 11 reviewed studies used 14 assessments. These assessments included: researcher-developed assessments, state assessments, practice tests and field test items related to a state assessment, commercial assessments, and other assessments developed by districts or research organizations (see Table 4). Four of the 14 assessments studied were either developed or modified by the researcher (Beckham, 2015; Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014). The researcher-developed assessments typically contained items selected or adapted from existing tests, such as state English language arts, math, and science tests; the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP); and Trends in International Math and Science Study (TIMSS). State assessments were included as measures in three studies (Deysson, 2013; Kuti, 2011; Roohr & Sireci, 2017). Typically, these were state assessments of mathematics, English language arts, or science, but Kuti (2011) examined accommodations for ELs with disabilities on the state English language proficiency assessment. An additional three studies incorporated measures such as state assessment practice tests or field-test items (Beckham, 2014; Cawthon et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017).

Table 4. Types of Assessment in Reviewed Research

| Type of Assessment |

Number of Studiesa |

| Researcher-developed assessment |

4 |

| State assessment items |

3 |

| Practice test or field test related to state assessment |

3 |

| Other |

2 |

| Commercial assessment |

1 |

a Deysson (2013) incorporated both state assessment items and an “other” assessment developed by the district. The exact nature of the assessments was not clear.

Two of the assessments were developed by other entities such as a school district or a research organization (Deysson, 2013; Robinson, 2010). For example, Robinson (2010) used data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten (ECLS-K) math assessments created by the Educational Testing Service (ETS) for a long-term research study. Deysson (2013) used a district-developed math assessment aligned to state standards as one of her measures. Finally, one study (Alt et al., 2013) used a commercially available assessment, the KeyMath-3. The KeyMath-3 is a clinical assessment of math skills developed by Pearson.

Most of the studies (n=10) used just one assessment (Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Cawthon et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Kuti, 2011; Robinson, 2010; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014). Of these, two studies contained multiple sub-studies using a smaller sampling of items from a larger common set (Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Young et al., 2014). Three studies used one test but made an adapted version of that assessment to examine the effect of linguistically modified items (Beckham, 2015; Cawthon et al., 2013; Young et al., 2014). For example, Beckham (2015) created a Spanish-enhanced version of a published state assessment practice test. The researcher kept the original English items from the practice test but added Spanish versions of items for students who could not answer the English items correctly. For studies of modified English, Cawthon et al. (2013) and Young et al. (2014) administered both original and modified versions of the same items. One study (Deysson, 2013) did not clearly indicate the number of assessments used. A full list detailing the type of assessment used in each study appears in Appendix B.

Content Area Assessed

In the studies examined, researchers used assessments of five key academic content areas: mathematics, reading/language arts, social studies, science, and English language proficiency. As shown in Table 5, accommodations for mathematics assessments were most commonly studied, with use in seven of the 11 studies (Alt et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Deysson, 2013; Robinson, 2010; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014). The next most commonly assessed content area was science (Cawthon et al., 2013; Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Young et al., 2014), followed by reading/language arts (Beckham, 2014; Cohen et al., 2017). Social studies (Roohr & Sireci, 2017) and English language proficiency (Kuti, 2011) were examined in one study each. The majority of the studies addressed only one of the content areas, but three studies (Cohen et al., 2017; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Young et al. 2014) addressed multiple content areas. See Appendix C for more detail.

Table 5. Content Areas Assessed

| Content Areas Assessed |

Number of Studiesa |

| Mathematics |

7 |

| Science |

3 |

| Reading/Language Arts |

2 |

| Social Studies/History |

1 |

| English Language Proficiency (ELP) |

1 |

aThree studies assessed more than one content area.

Type of Accommodation

The 11 reviewed studies documented a variety of different accommodations. As shown in Table 6, four studies addressed a form of a Spanish translation (e.g., complete translation or a Spanish enhancement of an English test; Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Deysson, 2013; Robinson, 2010). Deysson (2013) used a modified-English with a Spanish “enhancement” (i.e., translation) on items students did not answer correctly in English. Four studies examined modified or simplified English (Cawthon et al., 2013; Deysson, 2013; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Young et al., 2014). Three of the studies modified the English wording of all of the items on the test (Cawthon et al., 2013; Deysson, 2013; Roohr & Sireci, 2017) and one (Roohr & Sireci, 2017) allowed students to choose to see a chunk of text in a simplified version (i.e., sticker paraphrasing tool) during a computerized test administration.

Table 6. Types of Linguistic Support Accommodation in Reviewed Research

| Accommodation |

Type |

Linguistic

Support |

Number

of Studiesa |

Studied Alone or

in Combination |

Spanish translation or

enhancement of test |

Presentation |

Direct |

4 |

Alone=3

Combination=1 |

| Modified English |

Presentation |

Direct |

4 |

Alone=1

Combination=3 |

| English glossary |

Presentation |

Direct |

3 |

Alone=2

Combination=1 |

| Read aloud |

Presentation |

Direct |

1 |

Alone=1 |

| Illustrations |

Presentation |

Direct |

1 |

Alone=1 |

| Other/Unclearb |

|

|

2 |

Combination=2 |

a Some studies assessed more than one accommodation and are marked in multiple categories.

b Two studies listed multiple accommodations offered, either alone or in combination, that were not described in detail.

Three studies examined English glossaries (Cohen et al., 2017; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Wolf et al., 2012). One study each examined read aloud accommodations (Wolf et al., 2012) and use of illustrations (Solano-Flores et al., 2014). Two studies (Cawthon et al. 2013, Kuti, 2011) did not describe all accommodations offered in detail. For example, Kuti’s study of ELs with disabilities (2011) listed some specific accommodations offered to support students’ disability-related needs (e.g., scribe, computer assisted administration, audio amplification, braille, magnification, and large print booklets). However, Kuti indicated that there were other general types of accommodations offered that might have supported students’ linguistics needs including: modified test directions, modified timing, and modified presentation format. The exact nature of these other accommodations was unclear. Similarly, Cawthon et al. (2013) studied a package of test item modifications to enhance accessibility. The item modification process could potentially be considered an accommodation if offered to only some test takers. Of the modifications, only linguistic modification was clearly identifiable. Cawthon et al. did not describe in detail other elements included in the total package (e.g., visuals, formatting, graphics).

As Table 6 shows, the accommodations from the reviewed research had two primary characteristics in common. First, they were all presentation accommodations, meaning that the accommodation supports learners by adapting the presentation of the assessment content in some way. The read aloud accommodation, for example, changes the presentation of the content from written to oral. Second, all of the accommodations offer direct linguistic support. These accommodations offer adjustments to the language of the assessment in order to lessen the linguistic load needed to access the test content.

Finally, seven of the studies isolated single accommodations to study their effectiveness (Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Cohen et al., 2017; Robinson, 2010; Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012, Young et al., 2014). In contrast, four of the studies combined multiple accommodations into one study (Cawthon et al., 2013; Deysson, 2013; Kuti, 2011; Roohr & Sireci, 2017), either offering students simultaneous use of more than one accommodation or analyzing a large data set where students may have used multiple accommodations. For more details on the types of accommodations offered, see Appendix D.

Research Sample Sizes and Participant Characteristics

Some of the 11 studies reviewed had multiple sub-studies, each with its own sample. The samples in these studies varied in the number of total student participants, and the number of student participants identified as ELs. The number of research participants ranged from 21 students to over 52,000 students. As shown in Table 7, the majority of the study samples included 500 or more student participants (Cawthon et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Kuti, 2011; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Solano-Flores et al., 2014 - Study One; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014–Study One). These studies typically involved conducting analyses of existing large-scale data sets for state tests administered for accountability purposes. Four samples had 99 or fewer participants (Alt et al., 2013, Beckham, 2015–Studies 1 and 2; Deysson, 2013). Robinson (2010) had a variable sample size across years. The researcher examined assessment data for students in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Class of 1998-1999 (ECLS-K). The size of the sample started out at 1,618 Spanish-speaking students who began the study as kindergarteners, and it decreased to 576 students by the end of the second year due to factors associated with the research design. A major reason for the decrease was that students needed to stay within a particular score range on a language proficiency assessment to remain in the study across years. For more details on study participants and their characteristics see Appendices E and F.

Table 7. Number of Participants in Study Samples

| Number of Participants |

Number of Samples |

| 1-99 |

4 |

| 100-499 |

2 |

| 500-999 |

2 |

| 1000 or more |

5 |

| Variable size |

1 |

Table 8 indicates that six of the 11 studies had research samples made up of 100% ELs as the primary participants (Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Deysson, 2013; Kuti, 2011; Robinson, 2010; Solano-Flores et al., 2014). In the remaining five studies, fewer than 75% of the sample participants were ELs. Two studies (Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Wolf et al., 2012) had samples with between 50% and 74% ELs. One study had between 25% and 49% ELs (Young et al., 2014). In two studies (Cohen et al., 2017; Cawthon et al., 2013) less than a quarter of the study sample was ELs. Of these, the study with the lowest percentage of ELs in its sample, Cohen et al. (2017), performed an analysis of an existing state assessment database in which ELs represented 12% of third graders and 5% of seventh graders. They examined accommodations use for this subset of the total population tested. Cawthon et al.’s study also included an analysis of an existing database of test data in which ELs made up approximately 5% of the total tested population.

Table 8. Percent of Research Sample Consisting of ELs

Percent of Sample

Consisting of ELs |

Number of Studies |

| 1-24% |

2 |

| 25-49% |

1 |

| 50-74% |

2 |

| 75-99% |

0 |

| 100% |

6 |

Participants in the reviewed research ranged in grade level from elementary (K-5) to middle school (6-8) and high school (9-12). As Table 9 shows, more studies addressed elementary school (Alt et al., 2013; Cawthon et al., 2013; Deysson, 2013; Robinson, 2010) and multi-grade level samples (Cohen et al., 2017; Kuti, 2011; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014) than middle school or high school. Two studies examined high school students (Beckham, 2015; Roohr & Sireci, 2017); only one looked at accommodations use for middle school students (Solano-Flores et al., 2014).

Table 9. Summary of Participant Grade Levels in Reviewed Research

| Participant Grade Level |

Number of Studies |

| Elementary (grades K-5) |

4 |

| High School (grades 9-12) |

2 |

| Middle School (grades 6-8) |

1 |

| Multiple Grade Level Clusters (K-12) |

4 |

Ten of the 11 studies (Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Cawthon et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Deysson, 2013; Kuti, 2011; Robinson, 2010; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014) identified the ELs in their study samples as being either completely or largely Spanish speaking. Young et al. (2014) did not identify students’ language backgrounds. Three studies (Cohen et al., 2017; Kuti, 2011; Wolf et al., 2012) noted that other languages besides Spanish were present in their study samples, but did not specify the number of ELs in the samples who spoke each language. Kuti’s (2011) sample included Korean and Vietnamese speakers. The sample for Wolf et al. (2012) included Vietnamese, Arabic, Bengali, Danish, Hmong, Mandarin Chinese, and Punjabi speakers. Studies including speakers of other languages in their samples did not disaggregate results by students’ language backgrounds. Appendix F provides a detailed description of the student characteristics addressed by each of the 11 studies.

In addition to home language background, several studies described students’ English proficiency (ELP) levels in some way, but did not necessarily disaggregate results by these proficiency levels (Beckham, 2015; Deysson, 2013; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Wolf et al., 2012). Beckham (2015) chose students with intermediate levels of English proficiency as study participants but did not disaggregate results by ELP levels. Deysson (2013) examined students’ performance on a statewide English language proficiency assessment and reported that the study analyses included students in the lowest four levels. Deysson disaggregated study results by English proficiency level, but combined students in proficiency levels one and two, and three and four. Roohr and Sireci (2017) included ELs at intermediate and advanced levels of English proficiency in their study and did disaggregate findings by ELP level. Wolf et al. (2012) collected, but did not report, students’ English proficiency levels. Wolf et al. did disaggregate their data by students who were current ELs and recently exited ELs. Recently exited ELs would be those at higher levels of English proficiency.

Researchers listed many other types of student characteristics that were present in study samples. These included: (a) students’ language dominance in their home language and English (Alt et al., 2013); (b) socioeconomic status (Cawthon et al., 2013; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Wolf et al., 20112); (c) proficiency on state content assessments (Cawthon et al., 2013; Wolf et al., 2012); (d) special education status (Kuti, 2011); (e) years in U.S. schools (Roohr & Sireci, 2017); (f) course enrollment patterns (Roohr & Sireci, 2017); (g) primary language used in instruction (Deysson, 2013); and (h) geographic location (Solano-Flores et al., 2014). Of those other characteristics, language dominance (Alt et al., 2013) and content proficiency (Wolf et al., 2012) were factored into study results. Alt et al.’s study examined the use of a Spanish-enhanced assessment, with items initially provided in English, and then later provided in Spanish if a student got an English item wrong. The researchers looked at the relationship between student performance on the English and Spanish versions of items and a student’s language dominance. Wolf et al. (2012) examined whether students’ proficiency in math, as determined by past state assessment scores, was related to the effectiveness of both an English glossary and a read aloud accommodation.

Research Design

Five of the EL accommodations studies used a quasi-experimental research design (Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Deysson, 2013; Robinson, 2010; Solano-Flores, 2014). These studies (see Table 10) examined student performance with accommodations, but did not incorporate random assignment of students to accommodated and non-accommodated conditions. One study (Robinson, 2010), was identified by the researcher as a rigorous quasi-experimental study of a longitudinal database containing assessment data. The second most common research design was non-experimental descriptive qualitative analyses (Beckham, 2015; Cawthon et al., 2013; Kuti, 2011; Wolf et al., 2012) such as think alouds or interviews. The researchers used this design to gain an understanding of students’ and educators’ perspectives on accommodations. Research typically combined descriptive qualitative analyses with another type of research design. For example, Wolf et al. (2012) combined an experimental study with a randomized design and student think alouds to determine how ELs comprehended and solved math assessment problems.

Table 10. Research Designs

| Research Design |

Studiesa |

| Quasi-experimental |

5 |

| Non-experimental |

4 |

| Experimental |

2 |

| Descriptive quantitative |

2 |

aFour studies contained more than one research design.

Two studies were experimental studies (Cohen, 2017; Wolf et al., 2012) that randomly assigned students to accommodated and non-accommodated conditions to compare the performance of each group. Finally, two studies (Cawthon et al., 2013; Kuti, 2011) were descriptive quantitative studies that examined existing large assessment data sets to describe patterns of accommodation use and student performance with the accommodation. As noted in the table footnote, some studies (Beckham, 2015; Cawthon et al., 2013; Kuti, 2011; Wolf et al., 2012) contained multiple sub-studies and therefore had more than one research design. See Appendix G for detailed information.

Data Collection Methods

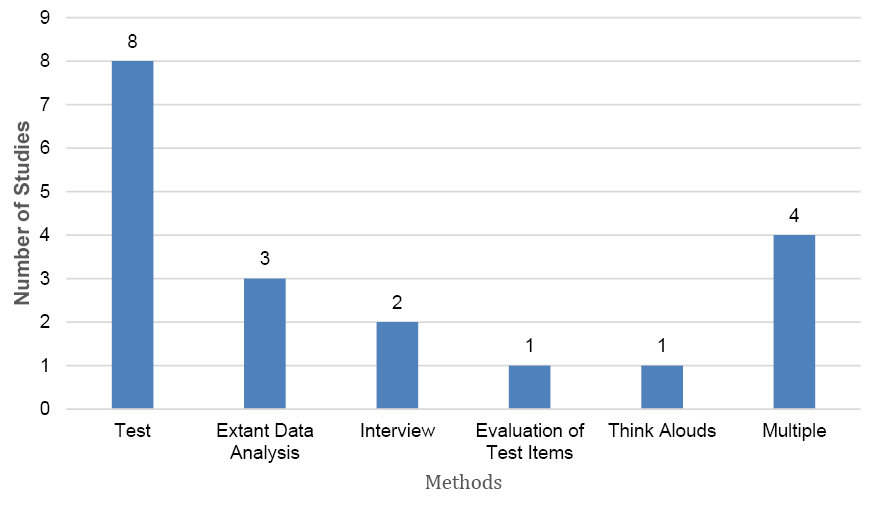

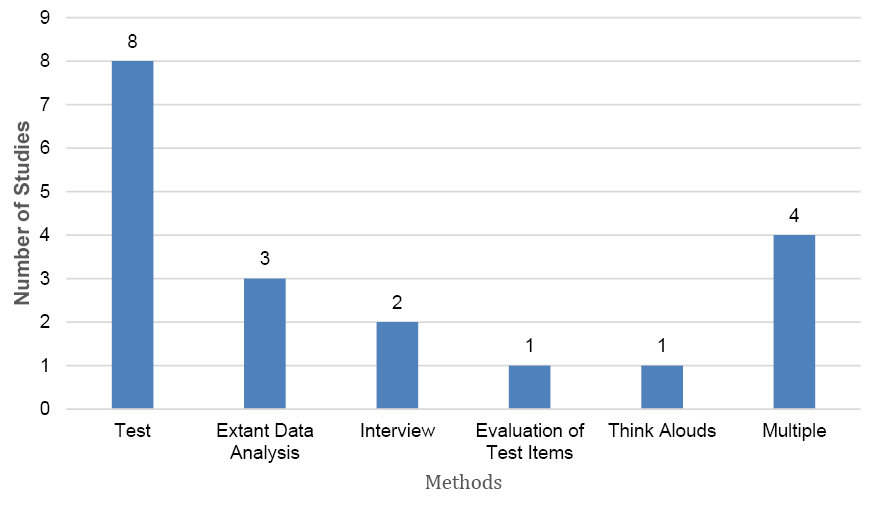

Researchers collected study data using a variety of methods (see Figure 1). Most studies (n=8) administered an assessment to examine the effectiveness of accommodations. (For more detail, see Appendix H.) Three studies (Cawthon et al., 2013; Kuti, 2011; Robinson, 2010) performed analyses of an existing assessment data set where students used accommodations. Two studies interviewed students or educators to find out their perceptions of test accommodations (Beckham, 2015; Kuti, 2011). One study performed a qualitative evaluation of modified assessment items to determine their accessibility for ELs (Cawthon et al., 2013). One study incorporated think alouds with students to find out more about students’ thought processes as they were solving assessment items (Wolf et al., 2012). Four of the studies reported using more than one method of collecting data. For example, Wolf et al., (2012) administered an assessment with and without accommodations and conducted think alouds on a subset of the items.

Figure 1. Data Collection Methods Used by Included Studies

Research Results

Results of the 11 accommodations research studies that we reviewed, organized by research design, are summarized in Table 11 (see Appendix H for more detail). The effects of accommodations were mixed. Four studies found that the use of the accommodation improved test scores for all ELs who used the accommodation (Alt et al., 2013; Beckham, 2015; Deysson, 2013; Robinson, 2010). These studies addressed studies of Spanish language translation and linguistic modification (i.e., simplification), or a combination of the two (see Deysson, 2013). Another three studies found that the accommodation studied supported improved assessment performance for some ELs who used it in some testing conditions (Cawthon et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2012–read aloud). For example, Cohen et al. (2017) examined the effectiveness of a pop-up English glossary and found that it was more effective at seventh grade compared to third grade. Two studies found that the accommodation did not improve the scores of ELs who used it (Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012). These accommodations were illustrations designed to enhance item comprehensibility (Solano-Flores et al., 2014) and an English glossary printed into paper test booklets (Wolf et al., 2012). Factors related to the observed lack of effectiveness included students’ level of familiarity with the accommodation (Wolf et al., 2012) and the lack of systematic accommodations delivery, particularly for the read aloud accommodation (Wolf et al., 2012). Wolf et al. (2012) noted that ELs tended to perform better with a read aloud when there was a script provided to test administrators so that all students took the test under a standard set of conditions.

Table 11. Summary of Research Findings on the Effectiveness of Accommodations for ELs

| Result |

Study |

Accommodation |

Total |

The accommodation supported

improved assessment performance

of ELs who used it |

Alt et al. (2013) |

Spanish Translation |

4 |

| Beckham (2015) |

Modified English |

| Deysson (2013) |

Modified English +

Spanish Translation |

| Robinson (2010) |

Spanish Translation |

The accommodation supported

improvement in assessment

performance for some ELs in

some testing conditions |

Cawthon et al. (2013) |

Modified English +

other/unclear (Multiple) |

3 |

| Cohen et al. (2017) |

Pop-up English glossary |

| Wolf et al. (2012) |

Read aloud |

The accommodation did not

support improved scores |

Solano-Flores et al.

(2014) |

Illustrations |

2 |

| Wolf et al. (2012) |

English Glossary |

| Unclear |

Kuti (2011) |

Other/unclear (Multiple) |

1 |

Did not examine effectiveness

of accommodations |

Roohr & Sireci (2017) |

Pop-up glossary and

sticker paraphrasing tool |

1 |

One study, Kuti (2011), did not show a clear pattern of results related to the effect of accommodations. This analysis of existing data collected by a state addressed all accommodations offered to ELs with disabilities during a statewide English language proficiency assessment. Kuti’s results showed that students offered the accommodations performed lower on the assessment than those who did not have accommodations. Still, the state did not track whether students actually used the offered accommodations. Thus, there was no way of knowing whether the accommodations, if used, were effective. Finally, although Roohr & Sireci (2017) conducted what they described as an experimental study with accommodated test forms randomly assigned to students, they did not examine the effectiveness of the pop-up glossary and sticker phrasing tool accommodations. Instead, their study examined patterns of students accommodations use.

Limitations Identified by Authors

The researchers of nine of the 11 studies discussed limitations that provided context for the results they reported. Table 12 presents the categories for the 46 limitations noted by researchers in the areas of methodology, sample characteristics, results, and test/test context. (For more details, see Appendix I.) Eight of the studies identified more than one category of limitation.

Table 12. Categorized Limitations Described by Study Authors

| Limitation Category |

Number of Studiesa |

Total Number

of Limitations |

| Methodology |

7 |

18 |

| Test/Test context |

7 |

14 |

| Sample characteristics |

7 |

11 |

| Study results |

3 |

3 |

| None |

2 |

Not applicable |

a Eight studies cited limitations in more than one category.

The three most commonly reported categories of limitations were in methodology, test/test context, and sample characteristics. Methodology limitations generally referred to errors in study design or data collection and analysis. Seven studies listed at least one methodology limitation (Beckham, 2015; Cawthon et al., 2013; Deysson, 2013; Kuti, 2011; Robinson, 2010; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Young et al., 2014). There were 18 limitations listed related to methodology. For example, Kuti (2011) indicated that ELs with disabilities included in the study may have been incorrectly identified. Misidentification may have led to linguistic or disability-related accommodations being inappropriate for their needs. The next most frequent category test/test context, listed by seven studies (Alt et al., 2013; Cawthon et al., 2013; Deysson, 2013; Kuti, 2011; Robinson, 2010; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Young et al., 2014), included 14 limitations about test construction, the determination or provision of test accommodations for individual students, and test administration. This category also included limitations on the generalizability of findings to other assessments.

The third most common type of limitation, also listed by seven studies, was in sample characteristics (n=11 limitations). This category typically included small sample size, use of convenience sampling, or the limited nature of the sample (e.g., one language group, one grade level). The makeup of the sample led to issues with population representativeness, limiting the generalizability of the findings beyond the research participants. For example, Roohr and Sireci (2017) stated that their study results were not generalizable to ELs other than the high school students they studied. Finally, limitations related to study results, listed by three studies (Deysson, 2013; Wolf et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014; n=3 limitations) were the smallest category. This category included issues such as assignment of accommodations that students did not actually use, potentially confounding the study results (Wolf et al., 2012).

Table of Contents

Summary

This report provides an examination of the published EL accommodations literature between 2010 and 2018. It addresses the purpose of each study, the type of assessment, the content area assessed, the type of linguistic support accommodation examined, the characteristics of the research sample and the participants, the type of research design, the findings, and the author-identified limitations.

The most commonly cited purpose of these accommodations research studies was to determine the effect of accommodations use on test performance. Typically, researchers examined accommodations use for a state assessment administration or for a state assessment practice test or field test of items. Most studies examined accommodations use in math. Translation and modified English were studied slightly more often than other accommodations. All the accommodations examined were presentation accommodations and offered direct linguistic support. Most studies examined a single accommodation, but roughly one-third of them addressed a combination of accommodations administered simultaneously.

Slightly less than half of the studies included large sample sizes of 1,000 or more students. Slightly more than half of studies had samples made up of 75% or more ELs. However, a few studies had small percentages of ELs. Students in the reviewed studies ranged in grade from elementary to secondary school, but studies tended to address elementary students and multi-grade level clusters most often. All except one of the studies indicated their study samples were either completely or primarily Spanish speaking. A few studies included students from other language backgrounds but did not disaggregate accommodations data by language background. Slightly more than one-third of the studies described the students’ English proficiency levels, but only two of those specifically disaggregated data according to those English proficiency levels (Deysson, 2013 combined levels; Roohr & Sireci, 2017). One study (Wolf et al. 2012) disaggregated data by students’ status as current or former ELs. Study authors listed a variety of other student characteristics present in study samples. Only language dominance (Alt et al., 2013) and prior content knowledge (Wolf et al., 2012) were used as study variables to disaggregate findings.

Approximately half of the studies used a quasi-experimental research design that did not incorporate random assignment of students to accommodation and non-accommodation conditions. The second most common design was non-experimental descriptive qualitative analysis like think alouds or interviews. These qualitative analyses provided an understanding of student or educator perspectives on accommodations and were typically combined with other designs in a larger study. Only two studies were experimental (Cohen 2017; Wolf et al., 2012). The most common way for researchers to collect data on accommodations use or effectiveness was to administer a test with, or without, accommodations.

There were mixed findings on the effectiveness of accommodations. The literature was fairly consistent on the effectiveness of Spanish translations and modified English. Two studies of Spanish translations (Alt et al., 2013; Robinson, 2010), one study of modified English (Beckham, 2015), and one study that combined modified English and a Spanish translation (Beckham, 2015) found that the accommodation improved the performance of all ELs who used it. The majority of other studies either had mixed results (Cawthon et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2012–read aloud) or showed no improvement in test scores when an accommodation was used (Solano-Flores et al., 2014; Wolf et al., 2012–English glossary; Young et al., 2014). Researchers provided a number of reasons as to why the accommodation did not improve the performance of all ELs. For example, Wolf et al. (2012) determined that many ELs did not use the English glossary printed in their test booklets. Solano-Flores et al. (2014) hypothesized that non-ELs benefitted more from the use of visuals accompanying test items because the non-ELs read the text and looked at the visual. The ELs tended to either not read the text, or read it but did not comprehend it. In addition, the authors stated that ELs might have lacked the prerequisite problem-solving skills to be able to answer the science test questions. The ELs could not derive enough meaning from the visual alone to improve their performance. Young et al. (2014) determined the complexity of the assessment items used for their study might have affected the degree of impact that the linguistic simplification had.

Table of Contents

Implications

The results of this literature review indicate some new research in areas recommended by Kieffer et al. (2009, 2012), and Abedi and Ewers (2013). First, the research literature did include more studies of modified (i.e., simplified) English and English glossaries. Glossaries and simplified English have been two of the most studied accommodations in the past. Notably two of the three glossary studies in this review examined the use of a computerized pop-up English glossary. The computerized delivery allowed students to choose whether to see definitions of glossed words on screen, and in some cases, to have the glossary entries read aloud to them. Researchers provided limited data to examine the effectiveness of computerized pop-up glossaries, but the trend to examining new forms of traditional accommodations is encouraging. Studies of modified English did not show a consistent effect on student test scores. Two studies found that all ELs benefitted from a linguistically simplified test (Beckham, 2015; Deysson, 2013). However, in one of those studies (Deysson, 2013), the linguistically simplified test was also translated into Spanish so the effect of the linguistic modification was not easy to determine. In studies that noted mixed results, or no evidence of an effect for ELs (Cawthon et al., 2013; Young et al., 2014), authors cited issues such as the complexity and accessibility of the original test items as possible complicating factors. More complex items may still be complex even after the language is simplified (Young et al., 2014). In contrast, students may perform relatively well on items that have been developed from the beginning to be accessible to ELs, and the use of simplified English on those items may provide little added benefit. The field would benefit from additional studies examining the relationship between the characteristics of the test items and the degree of benefit a linguistic modification provides to ELs.

Second, the reviewed literature addressed three innovative accommodations. These included: (a) a Spanish-enhanced version of an English assessment with Spanish items available only when answers to English items were incorrect, (b) a sticker paraphrasing tool that allowed students to cover difficult text with a paraphrase, and (c) the use of illustrations designed to enhance text comprehension. Authors’ findings demonstrated improved test scores only for the Spanish-enhanced administration of English test items. The study including the sticker-paraphrasing tool (Roohr & Sireci, 2017) did not examine the effectiveness of the accommodation. The study examining the use of visuals (Solano-Flores et al., 2014) demonstrated no improvement in students’ test scores. It is important to note that if ELs have not had access to the content of instruction, accommodations on an assessment of that content will most likely not make substantial improvements in their scores even if the accommodation is effective at reducing linguistic barriers.

Third, Kieffer et al. (2009, 2012), and Abedi and Ewers (2013), recommended that more studies address the effectiveness of assessment accommodations for students with particular characteristics. The majority of the 11 studies in this review did not examine whether accommodations differentially supported students of varying characteristics. A few studies did examine the differential effect that accommodations played for students of varying English proficiency levels (Deysson, 2013; Roohr & Sireci, 2017; Wolf et al., 2012). Deysson (2013) found that all ELs benefitted from the Spanish translation of the modified English assessment administered, yet ELs in the lowest two English proficiency levels on the ACCESS for ELs test benefitted the most. Roorh and Sireci (2017) examined ELs’ use of a pop-up glossary and a sticker-paraphrasing tool. They found that ELs of mid-level English proficiency used the accommodations more often than students at the highest levels used them. Wolf et al. (2012) examined the effectiveness of two separate accommodations; an English glossary printed in the test booklet and a read aloud accommodation. They found that the results did not show increased performance with either accommodation by students from any one proficiency level. They stated that their sample included many more students at the medium and high English proficiency levels and therefore the data did not have enough power to show an effect of English proficiency levels, but that the difference in the number of students was small. Instead, the researchers found that students’ prior math achievement scores had a stronger relationship to improved performance when using both accommodations. Students with higher math scores tended to benefit more from the use of the accommodation than students with lower scores did.

In addition, one study examined the role of language dominance in the use of a translated test (Alt et al., 2013). All students in the study spoke two languages, both English and Spanish. However, the degree to which they used each language varied. The researchers found that Spanish-speaking students were more likely to benefit from a Spanish test translation if they were Spanish dominant rather than English dominant (Alt et al., 2013).

In some cases, study authors indicated that students did not necessarily use the accommodations offered to them (Kuti, 2011; Wolf et al., 2012). These findings emphasize that more work remains to be done on effective accommodations decision-making processes to match characteristics of ELs to the most appropriate testing supports. There is a continued need for more studies in this area. In addition, ensuring the collection of accurate information documenting student use of available accommodations should be a fundamental part of studies on the effectiveness of accommodations.

Table of Contents

References

Abedi, J., & Ewers, N. (2013). Accommodations for English language learners and students with disabilities: A research-based decision algorithm. Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium. Retrieved from https://portal.smarterbalanced.org/library/en/ accommodations-for-english-language-learners-and-students-with-disabilities-a-research-based-decision-algorithm.pdf

Abedi, J., Hofstetter, C. H., & Lord, C. (2004). Assessment accommodations for English language learners: Implications for policy-based empirical research. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 1-28.

Albus, D., Thurlow, M., Liu, K., & Bielinski, J. (2005). Reading test performance of English-language learners using an English dictionary. Journal of Educational Research, 98 (4), 245-253.

Alt, M., Arizmendi, G. D., Beal, C. R., & Hurtado, J. S. (2013). The effect of test translation on the performance of second grade English learners on the KeyMath-3. Psychology in the Schools, 50(1), 27-36.

Beckham, S. (2015). Effects of linguistic modification accommodation on high school English language learners’ academic performance. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL. Retrieved from http://nsuworks.nova.edu/fse_etd/3

Cawthon, S., Leppo, R., Carr, T., & Kopriva, R. (2013). Toward accessible assessments: The promises and limitations of test item adaptations for students with disabilities and English language learners. Educational Assessment, 18(2), 73–98. doi: 10.1080/ 10627197.2013.789294

Cohen, D., Tracy, R., & Cohen, J. (2017) On the effectiveness of pop-up English language glossary accommodations for EL students in large-scale assessments. Applied Measurement in Education, 30:4, 259-272, DOI: 10.1080/08957347.2017.1353986

Deysson, S. (2013). Equity for limited English proficient students regarding assessment and effectiveness of testing accommodations: A study of third graders. Doctoral dissertation. The George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

Kieffer, M. J., Lesaux, N. K., Rivera, M., & Francis, D. J. (2009). Accommodations for English language learners taking large-scale assessments: A meta-analysis on effectiveness and validity. Review of Educational Research, 79(3), 1168-1201.

Kieffer, M. J., Rivera, M., and Francis, D. J. (2012). Practical guidelines for the education of English language learners: Research-based recommendations for the use of accommodations in large-scale assessments. 2012 Update. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537635.pdf

Kopriva, R. J., Emick, J. E., Hipolito-Delgado, C. P., & Cameron, C. A. (2007). Do proper accommodation assignments make a difference? Examining the impact of improved decision making on scores for English language learners. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 26(3), 11-20.

Kopriva, R. J., Thurlow, M. L., Perie, M., Lazarus, S. S., & Clark, A. (2016). Test takers and the validity of score interpretations. Educational Psychologist, 51(1), 108-128.

Kuti, L. (2011). Accommodations for English language learners with disabilities on federally mandated English language proficiency assessments. Doctoral dissertation. Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA. Retrieved from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/ etd/2541

Pennock-Roman, M., & Rivera, C. (2011). Mean effects of test accommodations for ELLs and non-ELLs: A met-analysis of experimental studies. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30(3), 10-28.

Robinson, J. P. (2010). The effects of test translation on young English learners’ mathematics performance. Educational Researcher, 39(8), 582-590.

Roohr, K. C., & Sireci, S. G. (2017). Evaluating computer-based test accommodations for English learners. Educational Assessment, 22(1), 35-53.

Sato, E., Rabinowitz, S., Gallagher, C., & Huang, C. (2010). Accommodations for English language learner students: The effect of linguistic modification of math test item sets (NCEE 2009-4079). Washington DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED510556.pdf

Shyyan, V., Thurlow, M., Christensen, L., Lazarus, S., Paul, J., and Touchette, B. (2016). CCSSO accessibility manual: How to select, administer, and evaluate use of accessibility supports for instruction and assessment of all students. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). Retrieved from

https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/ CCSSO%20Accessibility%20Manual.docx

Solano-Flores, G., Wang, C., Kachchaf, R., Soltero-Gonzalez, L., & Nguyen-Le, K. (2014). Developing testing accommodations for English language learners: Illustrations as visual supports for item accessibility. Educational Assessment, 19(4), 267-283.

Thurlow, M., Quenemoen, R., & Lazarus, S. (2011). Meeting the needs of special education students: Recommendations for the Race to the Top consortia and states. Retrieved from: https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/Martha_Thurlow-Meeting_the_Needs_of_Special_Education_Students.pdf

Willner, L.S., Rivera, C.,, & Acosta, B.D. (2008). Descriptive study of state assessment policies for accommodating English language learners. Arlington, VA: The George Washington University Center for Equity and Excellence in Education. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED539753)

Wolf, M. K., Kao, J., Griffin, N., Herman, J. L., Bachman, P. L., Chang, S. M., & Farnsworth, T. (2008). Issues in assessing English language learners: English language proficiency measures and accommodation uses. Practice Review (Part 2 of 3). CRESST Report 732. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST). Retrieved from https://cresst.org/wp-content/uploads/R732.pdf

Wolf, M. K., Kim, J., & Kao, J. (2012). The effects of glossary and read-aloud accommodations on English language learners’ performance on a mathematics assessment. Applied Measurement in Education, 25(4), 347-374.

Young, J. W., King, T. C., Hauck, M. C., Ginsburgh, M., Kotloff, L., Cabrera, J., & Cavalie, C. (2014). Improving content assessment for English language learners: Studies of the linguistic modification of test items. ETS Research Report Series, 2014(2), 1-79. Retrieved from

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ets2.12023

Table of Contents

Appendix A

Purpose of Research

| Study |

Purpose |

| Determine the effect of the use of accommodation on performance of ELs |

Alt, M., Arizmendi, G. D., Beal, C. R., & Hurtado, J. S. (2013).

The effect of test translation on the performance of second grade

English learners on the KeyMath-3. Psychology in the Schools,

50, 27-36. |

Determine whether a Spanish-enhanced administration of a

standardized math assessment results in improved scores

for Spanish-speaking ELs. |

Beckham, S. (2015). Effects of linguistic modification accommodation

on high school English language learners’ academic performance.

(Order No. 3712090). Available from ProQuest Dissertations &

Theses A&I. (1709243563). |

Assess whether providing linguistic modification accommodations

increases EL student performance in a language arts assessment as

compared to a standard testing condition. |

Cawthon, S., Leppo, R., Carr, T., & Kopriva, R. (2013). Toward

accessible assessments: The promises and limitations of test item

adaptations for students with disabilities and English language

learners. Educational Assessment, 18(2), 73-98. |

Analyze the effects of adapted test items on the performance of

students with disabilities, ELLs, and a control group on science

and English language arts assessments. |

Cohen, D., Tracy, R., Cohen, J. (2017). On the effectiveness of

pop-up English language glossary accommodations for EL

students in large-scale sssessments. Applied Measurement in

Education, 30(4), 259-272. |

Assess the effectiveness and influence on validity of a computer-

based pop-up English glossary accommodation for ELs on math

and English language arts assessments. |

Deysson, S. L. (2013). Equity for limited English proficient

students regarding assessment and effectiveness of testing

accommodations: A study of third graders. (Order No. 3550425).

Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I. (1287056937). |

Determine the effects of mathematics assessments that are

linguistically modified and translated into Spanish on the

performance of Spanish-speaking LEP students. |

Kuti, L. M. (2011). Accommodations for English language learners

with disabilities in federally-mandated statewide English language

proficiency assessment. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section

A. Humanities and Social Sciences, 72(11). |

Examine the types of accommodations that are provided for ELs

with disabilities and whether or how they contribute to

achievement. |

Robinson, J. P. (2010). The Effects of test translation on young

English learners’ mathematics performance. Educational

Researcher, 39(8), 582–590. |

Determine whether native-language test translations improve ELs’ mathematics performance. |

Solano-Flores, G., Wang, C., Kachchaf, R., Soltero-Gonzalez, L.,

& Nguyen-Le, K. (2014). Developing testing accommodations for

English language learners: Illustrations as visual supports for item

accessibility. Educational Assessment, 19(4), 267–283. |

Measure the effectiveness of providing vignette illustrations as an

accommodation on the performance of EL and non-EL students. |

Wolf, M., Kim, J., & Kao, J. (2012). The effects of glossary and

read-aloud accommodations on English language learners’

performance on a mathematics assessment. Applied Measurement

in Education, 25(4), 347-374. |

Investigate whether providing glossary and read-aloud

accommodations increases EL students’ performance on a

math assessment in comparison to a standard testing condition.

Determine whether providing glossary and read-aloud

accommodations leaves non-ELL students’ performance

unchanged, as compared to the standard testing condition. |

Young, J. W., King, T. C., Hauck, M. C., Ginsburgh, M., Kotloff, L.,

Cabrera, J., & Cavalie, C. (2014). Improving content assessment for

English language learners: Studies of the linguistic modification of

test items. ETS Research Report Series, 1–79. |

Explore the impact of linguistic modification of test items on K-12 content assessments for ELLs and non-ELLs. |

| Study perception of accommodation use |

Beckham, S. (2015). Effects of linguistic modification accommodation

on high school English language learners’ academic performance.

(Order No. 3712090). Available from ProQuest Dissertations &

Theses A&I. (1709243563). |

Investigate the perceptions of EL students on the effectiveness

of test accommodations used to improve their test scores.

Compare ELs’ test achievement levels with their perceptions

on test accommodations. |

Kuti, L. M. (2011). Accommodations for English language learners

with disabilities in federally-mandated statewide English language

proficiency assessment. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section A.

Humanities and Social Sciences, 72(11). |

Examine the perceptions that exist on accommodations provided

on annual English language proficiency assessments. |

| Wolf, M., Kim, J., & Kao, J. (2012). The effects of glossary and read-aloud

accommodations on English language learners’ performance on a mathematics

assessment. Applied Measurement in Education, 25(4), 347-374. |

Examine student perceptions on the helpfulness of glossary and

read-aloud accommodations when taking a math assessment |

| Examine patterns of student accommodations use |

Roohr, K., & Sireci, S. (2017). Evaluating computer-based test

accommodations for English learners. Educational Assessment,

22(1), 35-53. |

Evaluate differences in decisions made by non-ELs and ELs in

their use of computer-based accommodations for history and

math assessments. |

Wolf, M., Kim, J., & Kao, J. (2012). The effects of glossary and read-

aloud accommodations on English language learners’ performance on a

mathematics assessment. Applied Measurement in Education, 25(4),

347-374. |

Determine how ELL students utilize a glossary accommodation. |

| Investigate the effects of accommodations on test score validity |

Cohen, D., Tracy, R., Cohen, J. (2017). On the effectiveness of pop-up

English language glossary accommodations for EL students in large-

scale assessments. Applied Measurement in Education, 30(4), 259-272. |

Investigate whether the accommodation helps ELs demonstrate

their content knowledge without decreasing the validity of an

assessment. |

Table of Contents

Appendix B

Type of Assessment

| Authors (year) |

State Assessment |

Researcher-developed

Assessment |

Commercial Assessment |

Other |

| Alt et al. (2013) |

|

|

KeyMath-3 translation into

Spanish |

|

| Beckham (2015) |

Florida Reading, Grade 10: Standards-Based Instruction (FCAT) test practice book |

Researcher modified version

of FCAT practice test |

|

|

| Cawthon et al. (2013) |

State-wide field test |

|

|

|

| Cohen et al. (2017) |

Statewide accountability ELA and Math Assessments |

|

|

|

| Deysson (2013) |

2001 Virginia Math Standards of Learning (SOL) Assessment |

|

|

District-developed math assessment aligned to Virginia standards and simplified |

| Kuti (2011) |

ACCESS for ELLs |

|

|

|

| Robinson (2010) |

|

|

Early Childhood Longitudinal

Program- Kindergarten Class

(ECLS-K) Math Assessments

based on commonly used

commercial assessment items

from the Test of Early Mathematics

Ability- 3rd ed., Woodcock-

Johnson III, and Peabody Individual

Achievement Test |

|

| Roohr & Sireci (2017) |

Statewide high school history and math assessments |

|

|

|

| Solano-Flores et al. (2014) |

|

Study 1: A set of 27 multiple-

choice science items in two

formats (illustrated, unillustrated)

Study 2: A subset of 16 illustrations

selected from the 27 used in the

first study |

|

|

| Wolf et al. (2012) |

|

Researcher-developed assessment

using released National Assessment

of Educational Progress (NAEP)

and Trends in International Math &

Science Study (TIMSS) items and

released items from states’

standardized math tests |

|

|

| Young et al. (2014) |

|

Researcher created assessment

using released items from math

and science tests, including

NAEP items. |

|

|

| Totals |

6 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

Table of Contents

Appendix C

Content Area Assessed

| Authors (year) |

Mathematics |

Science |

Reading/

Language Arts |

Social Studies |

English

Language

Proficiency |

Total |

| Alt et al. (2013) |

X |

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Beckham (2015) |

|

|

X |

|

|

1 |

| Cawthon et al. (2013) |

|

X |

|

|

|

1 |

| Cohen et al. (2017) |

X |

|

X |

|

|

2 |

| Deysson (2013) |

X |

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Kuti (2011) |

|

|

|

|

X |

1 |

| Robinson (2010) |

X |

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Roohr & Sireci (2017) |

X |

|

|

X |

|

2 |

| Solano-Flores et al. (2014) |

|

X |

|

|

|

1 |

| Wolf et al. (2012) |

X |

|

|

|

|

1 |

| Young et al. (2014) |

X |

X |

|

|

|

2 |

| Totals |

7 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

Table of Contents

Appendix D

Type of Accommodation

| Authors (year) |

Accommodations |

English

glossary |

Modified

English |

Spanish

translation |

Read

Aloud |

Illustrations |

Multiple |

Other/

Unclear |

| Alt et al. (2013) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| Beckham (2015) |

|

X |

*X |

|

|

|

|

| Cawthon et al. (2013) |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

| Cohen et al. (2017) |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Deysson (2013) |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

| Kuti (2011) |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

| Robinson (2010) |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| Roohr & Sireci (2017) |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

| Solano-Flores et al. (2014) |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| Wolf et al. (2012) |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| Young et al. (2014) |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| Totals |

2 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

*Beckham (2015) used a Spanish enhancement of a test in English.

Table of Contents

Appendix E

Study Participants

| Authors (year) |

Number of Total Participants |

Number of ELs |

Percent of ELs |

Grade-level of

Participants |

| Alt et al. (2013) |

21 |

21 |

100% |

2nd grade |

| Beckham (2015) |

30 (Quantitative)

5 (Qualitative) |

30 (Quantitative)

5 (Qualitative) |

100%

100% |

10th grade |

| Cawthon et al. (2013) |

16,369 |

679 |

4% |

3rd-5th grades |

| Cohen et al. (2017) |

Grade 3 Total: 12,216 (Math);

11,777 (English)

Grade 7 Total: 20,261 (Math);

9204 (English) |

Grade 3 ELs: 1435 (Math);

1396 (English)

Grade 7 ELs: 963 (Math);

428 (English) |

Grade 3 =12% ELs in Math

and English

Grade 7 = 5% ELs in Math;

4% ELs in English |

3rd and 7th grades |

| Deysson (2013) |

82 |

82 |

100% |

3rd grade |

| Kuti (2011) |

52,517 students (quantitative)

8 educators (qualitative) |

52,517 (quantitative)

Not applicable (qualitative) |

100% (quantitative)

Not applicable (qualitative) |

Grades 3-12 |

| Robinson (2010) |

1,815 in fall of kindergarten;

dropped to 1,079 in spring of

kindergarten and then to 576

in fall of first grade |

Not specific; Students with

low scores on an English

proficiency test were given

the test in Spanish. Students

with higher scores were given

the test in English. |

Unknown |

Kindergarten initially;

followed through first grade |

| Roohr & Sireci (2017) |

History: 2,521

Math: 2,521 |

History: 1,499

Math: 1,486 |

History: 59%

Math: 59% |

High School |

| Solano-Flores et al. (2014) |

Study 1: 728

Study 2: 80 |

Study 1: 222

Study 2: 40 |

Study 1: 30%

Study 2: 50% |

8th grade |

| Wolf et al. (2012) |

605 |

313 |

52% |

8th initially; followed

through 9th grade |

| Young et al. (2014) |

Study 1: 2,060

Study 2: 180 initially;

used data for 159 |

Study 1: 932

Study 2: 90 initially;

used data for 75 |

Study 1: 45%

Study 2: 47% in data

retained |

4th and 6th grades |

Table of Contents

Appendix F

Student Characteristics

| Student Characteristics |

Alt et al. (2013) |

Beckham (2015) |

Cawthon et al. (2013) |

Cohen et al. (2017) |

Deysson (2013) |

Kuti (2011) |

Robinson (2010) |

Roohr & Sireci (2017) |

Solano-Flores et al. (2014) |

Wolf et al. (2012) |

Young et al. (2014) |

| Languages spoken |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Spanish |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

*Yes |

Yes |

*Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Other specific

Other non-specific |

n/a

n/a |

No

No |

No

No |

*Yes

No |

No

No |

*Yes

No |

No

No |

No

No |

No

No |

Yes

n/a |

No

No |

Country/Region

of origin |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Ethnicity |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

| English proficiency levels |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Language dominance |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Socio-economic status |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Content proficiency levels |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Special Education Status |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Years in U.S. schools |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Course enrollment |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| Instructional language |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Geographic location |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

*Note: Two studies described the language backgrounds of all of the students participating in large-scale administration of a test, but did not necessarily describe the language backgrounds of students selected for the study sample.

Table of Contents

Appendix G

Research Design, Data Collection Methods and Types of Analyses

| Study |

Design |

Data Collection Method |

Analyses |

| Alt et al. (2013) |

Quasi-Experimental |

Test (KeyMath-3) |

t-test, correlations, regression |

| Beckham (2015) |

Study 1: Quasi-Experimental

Study 2: Non-Experimental |

Test

Interview |

t-test

qualitative analysis |

| Cawthon et al. (2013) |

Study 1: Descriptive Quantitative

Study 2: Non-Experimental |