Middle School Principals’ Perspectives on Academic Standards-based Instruction and Programming for English Language Learners with Disabilities ELLs with Disabilities Report 22 Kristi Liu, Martha Thurlow, Haesook Koo, Manuel Barrera September 2008 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Liu, K., Thurlow, M., Koo, H., & Barrera, M. (2008). Middle school principals’ perspectives on academic standards-based instruction and programming for English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 22). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Introduction The demographics of U.S. public schools are changing quickly. Given the rapid growth in the number of linguistically and culturally diverse students nationwide (National Center for Education Statistics, 2007), educators, and school administrators can expect to serve an increasingly diverse student body with potentially different learning needs from those of the native English speaking students they may have been primarily trained to teach. Students identified as English language learners (ELLs) make up a significant part of this linguistically and culturally diverse population. Many educators and school leaders grapple with how to help ELLs learn both social and academic English at the same time that they are required to learn grade-level standards-based content (Smiley & Salsberry, 2007). Educators also often struggle with making grade-level content accessible for students with disabilities (Jackson & Neel, 2006). Approximately 9% of all ELLs in U.S. public schools also have a disability (Zehler, Fleischman, Hopstock, Pendzick, & Sapru, 2003). Creating instructional adaptations for a group of students with special learning needs may not have been part of most mainstream educators’ and administrators’ preparation programs in the past (Lucas, 2000; Wakeman, Browder, Flowers, & Ahlgrim-Delzell, 2006) and few educators have been specifically prepared to address the instructional needs of ELLs with disabilities (Kohnert, Kennedy, Glaze, Kan, & Carney, 2003). Accurately differentiating between second language learning processes and a disability can be challenging for educators (Casey, 2006) and it is possible that some ELLs are over identified in particular disability categories while others are not identified as in need of services when, in fact, they are (cf. Albus & Thurlow, 2004; Y. Liu, Ortiz, Wilkinson, Robinson, & Kushner, 2008). When ELLs are identified as having a disability, most often they receive services for learning disabilities or speech language disabilities and typically these students are taught by mainstream classroom teachers for much of the school day (Zehler et al., 2003). ELLs with any type of disability require specially adapted instruction that meets both their language learning and their disability-related needs. The limited amount of research on the academic achievement of ELLs with disabilities (Albus & Thurlow, 2004; K. Liu, Albus, & Thurlow, 2006) shows that these students may have very low rates of passing standards-based content assessments, lower than both ELLs overall and students with disabilities overall. Low passing rates raise concerns about the accessibility of the instruction that ELLs with disabilities receive in the mainstream classroom. If students’ unique learning needs are met, ELLs with disabilities have the potential to demonstrate increased academic achievement and to become even more successful in standards-based classrooms (Barrera, Liu, Thurlow, & Chamberlain, 2006; Barrera, Liu, Thurlow, Shyyan, Yan, & Chamberlain, 2006). Supporting teachers and assisting them in learning new ways of teaching and creating accessible instruction on standards-based content is a high priority for raising achievement levels for ELLs with disabilities. According to Lucas (2000), creating school change so that more equitable academic outcomes are attainable by ELLs, and by implication for ELLs with disabilities as well, is a "moral obligation" (p. 10). Principals play key roles in creating and sustaining that change so educators have the skills and knowledge to meet the learning needs of all students, including ELLs with disabilities (Smiley & Salsberry, 2007). Doing so will require that, in addition to functioning as managers and parent and community liaisons, principals also act as instructional leaders (Smiley & Salsberry, 2007). The research and teaching literature charges instructional leaders with specific roles and responsibilities for better serving ELLs; these are doubly important for ELLs with disabilities given their low rates of academic success. The roles and responsibilities include:

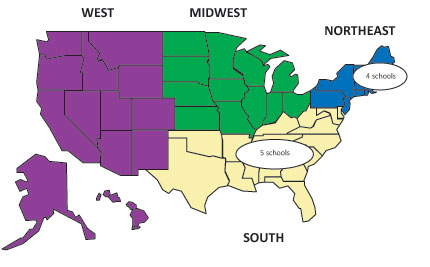

All of these roles, in addition to the more traditional roles associated with being a manager, supervisor, and liaison, are vital to the success of a school. However, providing direct support to teachers so that they have the resources and skills to appropriately instruct students with specific learning needs is perhaps the most crucial role for principals in a standards-based accountability system (Supovitz & Poglinco, 2001). Becoming a teacher of teachers (Stein & Nelson, 2003) requires principals to have personal experience and expertise with diverse students, even in situations where the size of a particular student group, such as ELLs with disabilities, is relatively small. Previous work by the National Center on Educational Outcomes (K. Liu, Koo, Barrera, & Thurlow, 2008) documented that principals in 10 "successful" middle schools (defined as those making Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) with ELLs and students with disabilities) were knowledgeable and concerned about the special education referral process for ELLs with disabilities but less knowledgeable about the characteristics of appropriate instruction for these students. Participants often answered questions about policies and practices for ELLs with disabilities by referring generally to policies and practices for ELLs, indicating that they may have lacked knowledge of the unique learning needs of ELLs with disabilities. Several participating principals stated that they either deferred instructional leadership for ELLs with disabilities to district curriculum and English as a second language (ESL)/bilingual specialists or delegated leadership responsibilities to an ESL/bilingual teacher in the school building. The district played a much stronger role in providing support to teachers in the appropriate use of instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities than did the state department of education or the school. K. Liu et al. (2008) raised the issue of whether the delegation model of instructional leadership was appropriate and useful in the participating schools that had all demonstrated success with standards-based outcomes. The findings suggested that more training may be required for principals on the specific instructional needs of students who have a combination of both language learning and disability-related learning needs. The purpose of this study was to follow up on the work of K. Liu et al. (2008) by working with another group of "successful" middle school principals (in schools making AYP with ELLs and students with disabilities) to extend the findings on instructional services and leadership for ELLs with disabilities. Specifically, we wanted to know about the following issues: (1) services and programs offered for ELLs with disabilities, (2) sources of instructional strategy information specific to ELLs with disabilities, and (3) the principal’s role in supporting teachers’ use of instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities. Participants The research team conducted the online principal survey simultaneously with another project-related study that examined teacher nominated instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities (Barrera, Shyyan, Liu, & Thurlow, 2008). Participating principals represented the same middle and junior high schools from which teacher participants were chosen for the Barrera et al. (2008) study. Data on the number of ELLs with disabilities are not generally made available by state departments of education, districts, or schools. Therefore, the team developed a process to identify schools with the greatest likelihood of serving ELLs with disabilities. Schools were selected using a multi-stage stratified random sampling procedure. First, using data from the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition we identified 10 states with the highest and 10 with the lowest ELL populations. For our purposes, the District of Columbia was included as a state. From these 20 states, 10 states (5 states with the highest and 5 states with the lowest ELL populations) were randomly drawn from the pool for inclusion in the first phase of grant project studies (Barrera et al., 2008; Shyyan, Thurlow, & Liu, 2008). The remaining 10 states became locations for the principal online survey and the related study of teacher-nominated instructional strategies. Second, within each of the 10 identified states the team created a list of middle and junior high schools making AYP during the 2003–2004 school year. Achieving AYP is one indicator of success in a standards-based system and entails achieving progress goals with English language learners and students with disabilities. We assumed that schools achieving AYP with ELLs and students with disabilities had increased academic outcomes for ELLs with disabilities as well. Because schools can change from year-to-year in whether they make AYP, we chose a common year based on the data that were publicly available from states. Third, from the list of schools making AYP the team identified the percentage of ELLs and students with disabilities enrolled at each of the middle and junior high schools (grades 6–9) and rank ordered the schools by the size of these student subgroups. We chose the top ranked schools in each state as potential study sites. In some cases there were enough schools that we could randomly identify five schools from within this pool in which to begin study recruitment. In other cases, there were few, if any, schools that met all of our criteria and we contacted all possible study sites. Within a particular state, the first principal who responded and agreed to take part in the study was selected as a participant. In schools with more than one principal we invited all interested school leaders to participate. Two recruitment issues affected our research design. In one Western state with a large ELL population we were unable to secure district-level permission for school principals to participate despite principal interest in the study. We attempted to recruit principals from other districts in that state but met with similar reluctance on the part of districts. Therefore, the team decided to drop that state from the research study. Additionally, in one small ELL state few schools met our participation criteria exactly. We made the decision to recruit a high school in this state because 9th graders attended the school and this was a grade-level included in our focus. We originally began this multi-stage sampling procedure using 2003–2004 data on schools achieving AYP and 2003–2004 school demographic data. However, by the time this component of the larger project began in the summer of 2007, several of the schools we had identified as potential research sites no longer existed in the same structure. Some schools had restructured and served different grade levels, while others had become charter schools or magnet schools serving special populations of students and using specialized curricula (e.g., science and technology magnet or visual and performing arts magnet). For this reason, we began the process of school identification again, using the 2003–2004 list of schools making AYP, along with 2007–2008 school demographic data because 2003–2004 demographic data often were no longer publicly available. Figure 1 shows the concentration of participating principals in the four geographic regions of the United States. A total number of 11 principals (8 principals and 3 assistant principals) participated in this survey. Four of the schools in which they worked were located in the Northeast and five schools were in the South. Figure 1. Location of School Sites

Survey Development The principal survey described in this report was conducted as part of a larger project that set out to identify effective instructional strategies nominated by educators and administrators that would support improved academic achievement for middle school ELLs with disabilities in grade-level standards-based instruction (Barrerra et al., 2008; Shyyan et al., 2008). One part of the grant project addressed ways that principals of successful middle schools (defined as those making AYP with ELLs and students with disabilities in 2003–2004) translated to teachers instructional strategy information specific to ELLs with disabilities. We believed that state standards documents would provide a limited amount of support for teachers in this area and teachers would require increased instructional leadership in order to create accessible grade-level content instruction for students with both linguistic and disability-related learning needs. As a first step, project staff conducted semi-structured face-to-face interviews with a purposive sample of 10 middle school principals during 2006. Principal interview findings were rich and insightful but represented only a small sample of school leaders. Therefore, the research team developed an online version of the principal interview, with some extensions to elicit information similar in nature to the information raised in the face-to-face interviews. The online survey focused on school level standards-based instructional efforts as well as program supports for ELLs with disabilities. The survey (see the appendix) consisted of five parts. The first part of the survey addressed aspects of the school demographics that provided important contextual information for understanding instructional leadership practices. Principals were asked to describe the location of the school, the grades served, the total enrollment and the size of various subpopulations such as ELLs, students with disabilities, ELLs with disabilities, and students receiving free or reduced lunch. The second section included items about services and programs the school offered for ELLs with disabilities. First, the items addressed identification procedures for ELLs with disabilities. Then the survey asked about services and programs for ELLs with disabilities, factors affecting how the school served ELLs with disabilities, and specific supports that either the state agency or school district provided to promote standards-based achievement of ELLs with disabilities. The third component of the survey elicited information about strategies contained in reading, math, and science curricula. Specifically, we asked about the type of curriculum used in each subject, whether the curricula overall provided instructional strategies aimed at supporting the specific learning needs of ELLs, ELLs with disabilities, and students with disabilities, and ways that principals facilitated implementation of these curricula. The fourth section dealt with strategies identified in state standards and related documents. Items asked about the frequency, usage, and amount of instructional strategy adaptation by teachers for those strategies contained in state standards-based documents. A few items addressed the principal’s leadership in the selection of instructional strategies for teaching ELLs with disabilities. The fifth component of the survey elicited information about participating principals’ professional experience working as a school principal. The survey ended with a request for volunteers to talk with the research team by telephone to describe survey responses in more detail. Survey Pilot Before administering the survey, the team piloted it with nine middle school principals in a state that had not been identified as a potential research site. The pilot took place between July and September of 2006. Suggestions for item clarification and additional items were gathered from pilot survey participants. The research team then revised the survey based on the feedback received. Survey Administration The online survey was administered individually beginning in September of 2007 and ending in July of 2008. Securing the required school and district permissions sometimes required several weeks or months of effort per research site. As a result, as soon as all the necessary requirements were met, the principals were asked to go online to a specified Web site link and fill in the survey at their convenience. Data collected from the survey were processed using Microsoft Excel. Although some respondents indicated a willingness to participate in an additional telephone interview to clarify their survey responses, this portion of the study was not completed due to time constraints. School and Student Information Table 1 shows demographic profiles of the schools represented by participating principals. The majority of principals worked in middle or junior high schools that served students in grades 6–8 or 7-8. However, due to some variation in the way schools were configured one principal represented a K–8 school and an additional principal worked in a high school serving students in grades 9–12. There were six principals from states with small ELL populations (five in the South and one in the Northeast) and five principals from states with large ELL populations (two in the South and three in the Northeast). Geographic setting information on each school was obtained from the National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data. The geographic setting codes indicate the school’s location compared to populated areas (NCES, 1998). We used what are now referred to as the "Old Locale Codes." Since the time of the study, locale codes have been updated to reflect changes in the definition of rural areas (NCES, 2008). Schools were located in a variety of geographic settings. However, there were no urban schools that met all of our participation criteria. Table 1. School Demographic Information

Table 2 provides further contextual information about the size and student demographics of each school during the 2007–2008 academic year. These data may vary slightly from those for 2003–2004 but they were commonly available for all schools in our study sample. In 2007–2008 student enrollment figures ranged from a low of 166 students to a high of 1266 students with a majority of schools enrolling more than 500 students. There was also considerable variability in the percentage of students receiving free or reduced lunch in each school. To be consistent with other figures in the table, we converted the percent of students receiving free or reduced lunch to a whole number. In two schools more than half of the student body received free or reduced lunch (706 of 980 students and 697 of 1107 students), indicating that the schools primarily served students from low income backgrounds. In contrast, in another school less than one fourth of the enrolled students were from low income backgrounds (126 of 787 students). All of the participating principals worked in schools that had relatively large populations of ELLs for those schools making AYP in the same state. However, as Table 2 shows, some of the schools had fewer than 10 ELLs enrolled in 2007–2008. None of the participating schools served more than six ELLs with disabilities and a few had no ELLs with disabilities. Table 2. 2007–2008 Student Demographic Information

*= Data were unavailable

Table 3 lists the primary language backgrounds of the largest groups of ELLs in each school for 2003–2004, as provided by the participating principals. Many of the principals worked in schools that served Spanish-speaking ELLs. However, there were other languages represented, notably French and Asian languages. Table 3. The Language Backgrounds of the Largest Groups of ELLs

*= Data unavailable

Principal Background Table 4 provides demographic information on all the participating principals. Among the 11 principals, there were 5 females (4 principals and 1 assistant principal) and 6 males (4 principals and 2 assistant principals). These individuals had worked as a principal for between 3 and 39 years, with an overall mean of about 15 years. Principals’ length of tenure at their current school site ranged from one year to five years, with an average of about four years across participants. Table 4. Participants’ Demographic Information

Services/Programs for ELLs with Disabilities The first section of the survey asked principals to provide information about services and programs for ELLs with disabilities. Respondents were asked to describe policies and procedures used in their school for referring an ELL to special education. A summary of these responses is shown in Table 5. Table 5. School Policies, Procedures and Assessments for Referring ELLs to Special Education

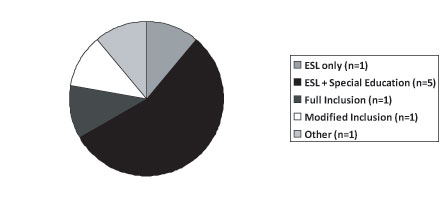

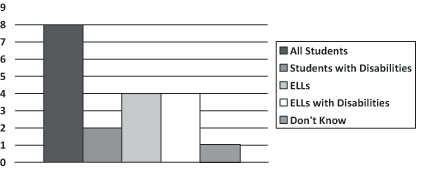

Most of the principals replied that the special education identification procedures for ELLs with disabilities were the same as for students who were not ELLs, indicating that there were no unique referral or assessment practices that took into account second language learning processes. A few of these same respondents stated that special education referral procedures were established by the district. Therefore, the school followed district policies for assessing all students. Typically, the district procedures were similar across states: formation of a child study team, meetings with parents, observation of the student in the classroom, and examination of student assessment results. As shown in Figure 2, when asked what types of programs and services were available to ELLs with disabilities, the majority of principals indicated that their school offered a combination of ESL and special education programming for English language learners with disabilities. Figure 2. Services for ELLs with Disabilities

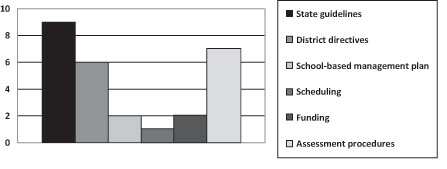

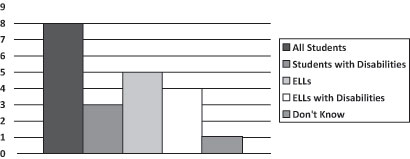

One school only offered ESL services to ELLs with disabilities, one offered full inclusion in a mainstream setting, and one offered modified inclusion. In a modified inclusion setting, a small number of students with disabilities might be placed in a mainstream classroom with a special education paraprofessional for support. The classroom teacher would plan instruction with the support of a special education inclusion specialist. The remaining principal indicated that the placement of an ELL with a disability depended on the severity of the child’s disability. "For example," he wrote, "an ELL student with mental retardation or severe handicapping condition would be in a self-contained special education class. Those that are at level three ELL may be in regular education classes supported with a resource teacher or inclusion setting." A variety of factors may influence the specific ways in which a school serves ELLs with disabilities. Figure 3 show the factors that principals reported to play the biggest role in shaping services for these students. All of the participating principals reported state guidelines as an important service determination factor for ELLs with disabilities. Special education assessment procedures and district directives were also common factors. Funding, school-based management plans, and scheduling influenced services in a few schools. Building space and staffing were not reported as factors by any principals. Figure 3. A List of Service Determination Factors for ELLs with Disabilities

Districts and state departments of education may play a role in supporting educators through the provision of information and training about the instruction of students with special needs. We asked principals whether their district or state had provided instructional leadership in three particular areas: (1) distributing hard copy or electronic information on teaching ELLs with disabilities in standards-based classrooms, (2) sponsoring workshops and training sessions, or (3) collaborating with a professional organization to offer workshops and trainings. Table 6 shows their replies. Table 6. Supports Provided to Promote Standards-based Achievement of ELLs with Disabilities

Several principals reported that both state departments of education and school districts provided hard copy or electronic information to educators. Some had received information from both levels. In addition, both the school districts and the state education agencies had sponsored workshops or trainings, with the school district appearing to take the lead in this area. The school districts seemed slightly more likely than the states to collaborate with professional organizations to provide such training. One principal indicated that his teachers received information and training from a state agency, but also reported that the state agency did not provide any specific support.

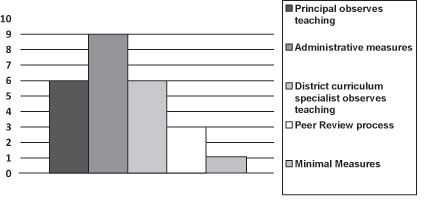

Instructional Strategies Associated with Content Curricula In previous interviews with other successful middle school principals in schools making AYP (K. Liu et al., 2008) some school leaders referred to instructional strategies suggested by curricula. For this reason, we asked principals in this online survey to provide information about their curricula in reading, math, and science. When asked about the curricula that the school used, response patterns were similar across each of the three content areas. All of the principals reported using a school or district-developed curriculum in reading. A few respondents reported using a combination of a school or district-developed curriculum and commercial curriculum in each content area. In math and science, the majority of states again reported using a school or district-developed curriculum with a small number also using a commercial curriculum. Only one state reported using solely a commercial curriculum in math and science. We then asked principals whether the school used different curricula in reading, math, and science for ELLs, students with disabilities, and ELLs with disabilities. The patterns of responses were, again, very similar across states for each of the three content areas. Two states had separate curricula in reading and math for English language learners (only one of the two had separate curriculum in science for ELLs). Three other states had separate curricula in all content areas for students with disabilities. Three states had separate curricula only for ELLs with disabilities. One small state had a common curriculum in reading and math. That small state, along with a second small state, had only a common science curriculum for all students. These responses showed no discernible pattern according to whether a school was located in a state that had a large number of ELLs or a small number of ELLs. When teachers implement curricula in the classroom, instructional leaders follow up with teachers to determine whether adjustments in instruction need to be made at a building level, and an individual teacher level. Figure 4 contains the follow up strategies used by the nine principals in this study. Figure 4. Measures Used to Implement a New Curriculum

The most common type of follow-up procedure for principals was an administrative measure such as an accountability chart or performance checklist. Observations of teachers by either principals or district curriculum specialists were other common procedures to ensure that teachers were following content and instructional strategies as laid out by the curricula. One principal who reported using a teacher peer review process added the following comment about the instruction of ELLs in general:

The remaining principal used minimal measures to follow up on curriculum implementation. As a last question in this section of the survey, principals were asked whether their curricula in reading, math, and science contained instructional strategies that were specifically aimed at delivering grade-level content to specific groups of students. Figures 5 and 6 contain information relevant to this question. The answers for math and science curricula were identical in each state and were, therefore, combined into one table. Figure 5. Instructional Strategies Contained in Reading by Type of Student

Figure 6. Instructional Strategies Contained in Math and Science by Type of Student

Figures 5 and 6 highlight that, according to principal responses, most of the curricula used in these successful middle schools provided instructional strategies for the general student group. Strategies for ELLs were also relatively common. Several principals reported that reading, math, and science curricula contained instructional strategies specific to ELLs with disabilities, even though there were not many principals reporting that their curricula contained strategies for students with disabilities overall. It was not clear what these strategies for ELLs with disabilities were. One principal indicated a lack of familiarity with the instructional strategies contained in curricula in all three areas.

Other Sources of Instructional Strategy Information In addition to strategies contained in content curricula, teachers may rely on other sources of information to learn about ways to help students with special needs achieve in grade-level instruction. Principals or district-level staff may mandate the use of particular instructional strategies by all teachers. Principals in this survey provided information about strategies that they or their districts mandated in reading, math, or science for students with disabilities, ELLs, or ELLs with disabilities. Across all of the content areas, two principals reported that they did not know, implying that they did not know whether the district mandated any instructional strategies for these groups of students. One principal was certain that neither he nor his district mandated the use of any strategies for these students. The remaining principals’ responses can be summarized as follows:

A follow up item asked principals to describe the mandatory strategies that existed at the building or district level. Most principals (n=6) chose not to answer the question. Among the remaining three principals, two offered a brief description of instructional strategies in use and another provided a brief comment:

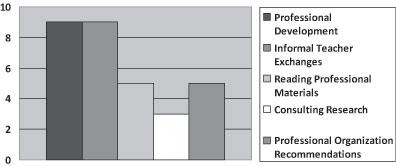

None of the comments listed by principals related directly to instruction of ELLs with disabilities. Previous research by Albus, Thurlow, and Clapper (2007) found that some states incorporated instructional strategies for students from special populations into their state standards and the supporting documents that described standards. We asked principals about the extent to which teachers of ELLs with disabilities used strategies contained in the state standards and supporting documents. All of the principals believed that teachers used these state-specified strategies. One principal in a large ELL state reported that teachers of ELLs with disabilities used state-specified instructional strategies extensively. Five principals reported that teachers of ELLs with disabilities used state-specified instructional strategies regularly. Three principals reported that teachers of ELLs with disabilities used these strategies somewhat. The majority of principals believed that teachers used the strategies as directed by the state, but then also adapted them to meet the needs of diverse students and combined them with strategies from other sources. As shown in Figure 7, principals stated that teachers in these nine schools primarily increased their effectiveness at using standards-based instructional strategies through professional development sessions and informal exchanges with other teachers. Teachers relied to a lesser extent on reading professional materials such as books and Web sites, consulting research literature, and following recommendations from professional organizations. Figure 7. Methods Used by Teachers to Increase Effective Use of Instructional Strategies

Principals supported teachers in improving instructional practice for ELLs with disabilities by sending them to professional development workshops (n=6), referring teachers to the district’s curriculum specialists (n=5), and providing books or other materials (n=3). One principal in a large ELL state reported the use of an outside consultant to help develop teachers’ skills:

Other Thoughts from Principals The survey finished with an open-ended item asking for any additional information on the principals’ efforts to help ELLs with disabilities meet academic standards. Five principals added a comment:

The additional comments provided by principals largely related to school-wide strategies for promoting the academic achievement of all students and did not specifically pertain to the instruction of ELLs with disabilities. This study was conducted with a small number of participants, and therefore the findings are not generalizable. However, given a relatively small pool of middle and junior high schools with diverse students that were making AYP, the views of these participants are extremely important. They represent views from leaders who have been successful at increasing standards-based academic achievement for ELLs and students with disabilities. Our assumption was that the principals would also have raised academic achievement for ELLs with disabilities at the same time. However, even in the largest schools associated with these nine principals there were fewer than six identified ELL with disabilities at the time of the study. Principals’ answers to questions reflected the view that perhaps the group of ELLs with disabilities was not sufficiently large enough to have become a pressing concern. These nine school leaders often reported that they followed district special education identification procedures, which were the same for all students. The fact that none of these principals mentioned specific identification processes associated with differentiating between a disability and second language learning is striking. Similarly, in these schools there was no single instructional program or service designed to meet the combination of language learning and disability-related needs of ELLs with disabilities. Rather, a blend of ESL and special education programming was standard practice. Typically, principals reported that the structure of services offered to ELLs with disabilities was primarily influenced by state guidelines, special education assessment procedures, and district directives. They did not report any school-level initiatives in place for the identification and instruction of this population of students. Survey respondents perceived instructional strategy information for English language learners with disabilities to come from four main sources: the curricula, individual principal or district mandated strategies, professional development opportunities provided by the district or state department of education, and informal teacher exchanges. Principals did mention that they supported teachers in developing their skills related to instructional strategy use for ELLs with disabilities by sending teachers to professional development workshops or referring them to district specialists. However, the district appeared to play the largest role in providing training opportunities and curriculum specialists to support teachers. The findings of this online principal survey echo the findings of the previous principal interviews (K. Liu et al., 2008) in two major areas. First, principals seemed to be less familiar with the details of instructing ELLs with disabilities than they were with instructing the total group of students. In anecdotal comments, principals described school-wide instructional practices such as differentiated instruction or the use of state test data to review student progress when asked to provide comments relating to standards-based instruction for ELLs with disabilities. They indicated they were aware of diverse instructional needs, such as those pertaining to ELLs. Likewise, when asked what strategies were mandated by the principal or the school district for ELLs with disabilities, but also for ELLs and students with disabilities, many principals stated that there were mandated strategies but did not describe them. These types of answers indicate that these school leaders may lack specific knowledge and experience with the instruction of ELLs with disabilities. A second key finding that was echoed in our previous study is that these nine principals deferred some of their role as instructional leader for ELLs with disabilities to the district. The districts often provided teacher training opportunities and direct support to teachers for the instruction of specific groups of students in ways that the principal did not. All of the schools represented in this study were schools that had successfully supported increases in standards-based content learning for ELLs, students with disabilities, and potentially ELLs with disabilities in the past. Deferring part of their instructional leadership role to more knowledgeable individuals with greater resources may have been an efficient and effective strategy. More research is needed to determine the extent to which principals could provide more direct instructional leadership for ELLs with disabilities if they had support in learning more about the students and whether direct leadership from the principal would make any difference in achievement scores. Albus, D., & Thurlow, M. (2004). Beyond subgroup reporting: English language learners with disabilities in 2002–2003 online state assessment reports (ELLs with Disabilities Report 10). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Albus, D., Thurlow, M., & Clapper, A. (2007). Standards-based instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 18). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Barrera, M., Liu, K., Thurlow, M., & Chamberlain, S. (2006). Use of chunking and questioning aloud to improve the reading comprehension of English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 17). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Barrera, M., Liu, K., Thurlow, M., Shyyan, V., Yan, M., & Chamberlain, S. (2006). Math strategy instruction for students with disabilities who are learning English (ELLs with Disabilities Report 16). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Barrera, M., Shyyan, V., Liu, K., & Thurlow, M. (2008). Reading, mathematics, and science instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities: Insights from educators nationwide (ELLs with Disabilities Report 19). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Casey, A. (2006). Case in point: Issues and challenges in educating English language learners with disabilities. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 19(1), 52–54. Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO]. (1996). Interstate school leaders licensure consortium: Standards for school leaders. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers. DiPaola, M., Tschannen-Moran, M., & Walther-Thomas, C. (2004). School principals and special education: Creating the context for academic success. Focus on Exceptional Children, 37(1), 1–10. Jackson, H., & Neel, R. (2006). Observing mathematics: Do students with EBD have access to standards-based mathematics instruction? Education and Treatment of Children, 29(4), 593–614. Kohnert, K., Kennedy, M., Glaze, L., Kan, P., & Carney, E. (2003). Breadth and depth of diversity in Minnesota: Challenges to clinical competency. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(3), 259–272. Liu, K., Albus, D., & Thurlow, M. (2006). Examining participation and performance as a basis for improving performance. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 19(1), 34–42. Liu, K., Koo, H., Barrera, M., & Thurlow, M. (2008). Middle school principals’ interpretation of state policy and guidance on instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 20). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Liu, Y., Ortiz, A., Wilkinson, C., Robertson, P., & Kushner, M. (2008). From early childhood special education to special education resource rooms: Identification, assessment, and eligibility determinations for English language learners with reading-related disabilities. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 33, 177–187. Lucas, T. (2000). Facilitating the transitions of secondary English language learners: Priorities for principals. National Association of Secondary School Principals [NASSP] Bulletin, 84(619), 2–16. National Center for Education Statistics. (2007). The condition of education 2007: Indicator six, language minority children. Retrieved July 30, 2008 from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2007064 National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. (2006). The growing number of limited English proficient students: 1995/96–2005/06. Retrieved July 30, 2008, from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/policy/states/reports/statedata/2005LEP/GrowingLEP_0506.pdf Shyyan, V., Thurlow, M., & Liu, K. (2008). Instructional strategies for improving achievement in reading, mathematics, and science for English language learners with disabilities. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 33(3), 145–155. Smiley, P., & Salsberry, T. (2007). Effective schooling for English language learners: What elementary principals should know and do. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education, Inc. Stein, M., & Nelson, B. (2003). Leadership content knowledge. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(4), 423–448. Supovitz, J., & Poglinco, S. (2001). Instructional leadership in a standards-based reform. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Retrieved July 30, 2008, from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/19/f3/9c.pdf Thurlow, M., Barrera, M., & Zamora-Duran, G. (2006). School leaders taking responsibility for English language learners with disabilities. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 19(1), 3–9. Wakeman, S., Browder, D., Flowers, C., & Ahlgrim-Delzell, L. (2006). Principals’ knowledge of fundamental and current issues in special education. National Association of Secondary School Principals [NASSP] Bulletin, 90(2), 153–174. Zehler, A., Fleischman, H., Hopstock, P., Stephenson, T., Pendzick, M., & Sapru, S. (2003). Descriptive study of services to LEP students and LEP students with disabilities (Volume I Research Report). Arlington, VA: Development Associates Inc. Retrieved July 30, 2008, from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/resabout/research/descriptivestudyfiles/volI_research_fulltxt.pdf NCEO Survey for Principals Please take 15–20 minutes to tell us about your school and instructional strategy use that may benefit English language learners (ELLs) with disabilities. As you answer the survey questions, we would like you to think about: middle school or junior high ELLs with identified or suspected disabilities; ELLs with disabilities who participate in grade-level standards-based content instruction (e.g., those with learning disabilities, speech-language disabilities, emotional-behavioral disabilities, mild-moderate mental retardation); and all teachers who work with grade-level standards-based content instruction for ELLs with disabilities (e.g., content area specialists, ESL teachers, special education teachers, resource room teachers, etc.). Student and School Demographics 1. What grades are served in your school? ___ 2. How many students are enrolled in the school this year? ___ 3. In what kind of

setting is your school located? 4. What percent of your total student body receive free or reduced lunch during the 2007–08 school year? ___ 5. How many of the

following types of students does your

school currently serve? Fill in all the

blanks 6. What are the language

backgrounds of your largest groups of

ELLs? Choose all that apply Services/Programs for ELLs with Disabilities 7. If your school identified ELLs with disabilities in the past or is likely to do it in the near future, what policies, procedures, or assessments do teachers use in referring an ELL to Special Education? Please list these below. ___ 8. What kinds of

services are offered or can be offered

in your school for ELL students with

disabilities? 9. Which of the

following determines how your school

serves ELLs with disabilities? Choose

all that apply 10. Please describe more specifically how these affect your school’s services for ELLs with disabilities. ___ 11. What specific supports does your state agency or school district provide to promote standards-based achievement of ELLs with disabilities in your school? Select all that apply

12. Are there any other supports that your state agency or school district provides to promote standards-based achievement in your school? ___ Reading, Math, and Science Curricula 13. Does your school use any of the following types of curricula in reading, math, and science for students in general? Select all that apply

14. Does your school diversify its curriculum for ELL students, students with disabilities, and ELL students with disabilities in the following content areas? Select all that apply

15.

What do you do to follow up with

teachers when a new curriculum

is implemented? Select all that

apply 16. Do your curricula in reading, math, and science contain recommended instructional strategies* specifically aimed at delivering grade level content to any of the following groups? (*Instructional strategies are purposeful activities to engage students in acquiring new behaviors or knowledge. These have clearly defined steps or a clear description of what the teacher does.) Select all that apply

Instructional Strategies 17. Do you or does your district require any additional instructional strategies in the following content areas for any of the following groups beyond those contained in the curricula? Select all that apply

18. If you identified additional instructional strategies that you or your district require for each content area and student group in Question 17 of the survey, please describe each strategy below. ___ 19. To what

extent do teachers of ELLs with

disabilities use instructional

strategies that may be

identified in state standards

and related documents? 20. How do

teachers use the instructional

strategies that may be contained

in state standards and

supporting documents? Select all

that apply 21. In addition

to state supported strategies

how do teachers increase their

own effectiveness in using

instructional strategies to help

students meet academic

standards? Select all that apply 22. How do you

assist your teachers in

selecting instructional

strategies for teaching ELLs

with disabilities? Select all

that apply 23. As a school that has been successful in meeting Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) requirements with all students, including ELLs with disabilities, what additional information would you like to share regarding your efforts to help ELLs with disabilities meet academic standards? ___ Demographic Information 24. How long have you been a principal? (years) ___ 25. How long have you been a principal in your current school? (years) ___ 26. We are very

interested in hearing more about

what you have to say relating to

successful instruction of ELLs

with disabilities. Would you

agree to participate in an

approximately 20 minute

telephone conversation with

researchers to discuss the

topics above in greater detail?

We would like to hear your

comments about any of your

answers above, any specific

initiatives your school or

district has undertaken relating

to instructional strategies and

any targeted efforts to improve

grade level content learning of

ELLs with disabilities. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||