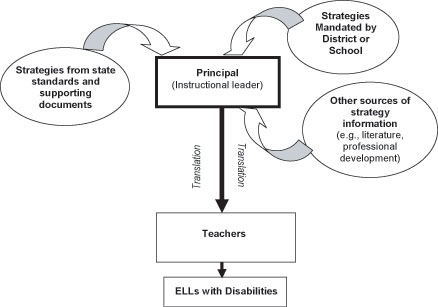

Middle School Principals’ Interpretation of State Policy and Guidance on Instructional Strategies for ELLs with Disabilities ELLs with Disabilities Report 20 Kristi Liu, Haesook Koo, Manuel Barrera, Martha Thurlow September 2008 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Liu, K., Koo, H., Barrera, M., & Thurlow, M. (2008). Middle school principals’ interpretation of state policy and guidance on instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 20). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Introduction For many years, federal laws have emphasized access to grade-level standards-based curriculum for all students. Results of statewide tests are disaggregated by identifiers such as race/ethnicity, disability, English proficiency, socioeconomic status, and mobility. Disaggregated results allow schools to examine instructional programming and access to the curriculum for specific subgroups of students. However, the needs of students with multiple identifiers are rarely examined and addressed. English language learners with disabilities (hereafter referred to as ELLs with disabilities) are a rapidly growing group of students in the United States whose achievement is affected by both second language learning processes and the presence of a disability. Although it is difficult to identify the exact number of ELLs with disabilities in public schools in the United States, one national study (Zehler Fleischman, Hopstock, Stephenson, Pendzick, & Sapru, 2003) estimated that 9.2% of all English language learners (ELLs) during the 2001–2002 school year also received special education services. The total number of ELLs had grown to more than five million students nationwide by 2005 (National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, 2006), and is expected to continue to increase. Using the Zehler et al. (2003) figure, a safe estimate is that there are at least half a million ELLs with disabilities attending public schools. Many students with disabilities, including ELLs with disabilities, now receive the majority of their instruction in mainstream classrooms (U.S. Department of Education, 2007; Zehler et al., 2003). For these students to achieve in grade-level content classrooms, educational practices must be aligned with student needs (Smiley & Salsbury, 2007). To support student learning, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) requires educators to use scientifically-based instructional practices. NCLB defines scientifically-based research as "research that involves the application of rigorous, systematic and objective procedures to obtain reliable and valid knowledge relevant to education activities and programs" (NCLB, 2001, §9101). There is a growing body of literature on research-based interventions for English language learners and students with disabilities (cf. Gersten, Baker, Shanahan, Linan-Thompson, Collins, & Scarcella, 2007; Sencibaugh, 2007; Stecker, Fuchs, & Fuchs, 2005; What Works Clearinghouse, 2007). However, there is relatively little evidence showing what effective programs and practices best meet the unique learning needs of ELLs with disabilities (Barrera, Liu, Thurlow, & Chamberlain, 2006; Barrera, Liu, Thurlow, Shyyan, Yan, & Chamberlain, 2006). It can be difficult for mainstream content teachers to differentiate between student learning challenges related to second language learning and those related to a student’s disability (Layton & Lock, 2002). Teachers may rely on strategies with which they are most familiar, even if these practices do not address all of their students’ learning challenges. For example, in studies by Barrera et al. (2006a, 2006b) many mainstream and English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers reported that they primarily used instructional strategies intended for typically-developing ELLs when working with ELLs with disabilities. Similarly, special education teachers in those same studies reported using instructional strategies aimed at supporting a student’s disability-related learning needs without necessarily incorporating strategies aimed at a student’s second language learning needs. These findings are not surprising given that the majority of educators are not trained in ways to adapt instruction to meet the specific needs of linguistically and culturally diverse students with disabilities in the classroom (Kohnert, Kennedy, Glaze, Kan, & Carney, 2003; Mueller, Singer, & Carranza, 2006). In many cases, teachers must develop these skills on the job. More than 10 years ago, the National Research Council (NRC, 1997) addressed the idea of creating changes in student academic outcomes through changes in instruction. "Real change in education comes through changes in content that teachers teach and students learn, and in the instructional methods that teachers use" (NRC, 1997, p. 113). With substantial support and resources on ways to change instruction so that it becomes more accessible, teachers can create improved learning outcomes on grade-level, standards-based content for ELLs with disabilities (Barrera et al., 2006a; 2006b). The question is, where do teachers get this kind of sustained support for change? School principals are central figures in the way instructional innovation is implemented and communicated to teachers in a particular school (Marks & Nance, 2007). It may have been typical in the past for principals to primarily be building managers with responsibility for hiring and firing staff, scheduling, and maintaining the school building. However, both professional organizations and the research literature underscore the fact that times have changed. In a standards-based system, principals must be both managers and instructional leaders if schools are to increase the academic achievement of all students (Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO], 1996; Marks & Nance, 2007; Smiley & Salsbury, 2007; Supovitz & Poglinco, 2001). "Instructional leadership…can play a central role in shifting the emphasis of school activity more directly onto instructional improvements that lead to enhanced student learning and performance" (Supovitz & Poglinco, 2001, p. 1). The Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium, or ISLLC, standards for principals emphasized that instructional leaders must infuse into every instructional decision the beliefs that all students can be taught and that all students can achieve high standards (CCSSO, 1996). According to these standards, an effective principal also must have knowledge of ways to plan appropriate instruction for a diverse student body so that the goal of high achievement for all students is translated into specific practices (CCSSO, 1996). However, the ISLLC standards do not define the term "diverse" to specifically include ELLs, students with disabilities, or ELLs with disabilities. Other sources advocate that principals need to understand how to implement standards-based instruction with linguistically and culturally diverse students (Catano & Stronge, 2006; Lucas, 2000) and students with disabilities (Wakeman, Browder, Flowers, & Ahlgrim-Delzill, 2006). ELLs with disabilities are not specifically mentioned in the instructional leadership literature, but if schools are to achieve the vision of academic success for all students, instruction must address the dual needs of ELLs with disabilities as well. To better understand how school principals can provide instructional leadership appropriate for ELLs with disabilities, the study described in this report examined how principals of successful schools translated information to teachers on designing accessible standards-based instruction for ELLs with disabilities. The intent of the study was to highlight promising practices that might be studied further, as well as to identify areas where principals may need additional support in providing instructional leadership for their teachers. Research Question This study was conducted as part of a larger investigation designed to identify effective instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities in grade-level standards-based instruction (Barrera, Shyyan, Liu, & Thurlow, 2008). As shown in Figure 1, the research team initially believed that principals, as instructional leaders for schools, would be directly involved in translating and communicating to classroom teachers principles of accessible instruction for diverse students. Our hypothesis was that information about instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities might come from a variety of original sources such as state standards and supporting documents (Albus, Thurlow, & Clapper, 2007), strategies mandated by the school or district, and other sources such as research literature and professional development opportunities. We believed that the principal would play a central role in disseminating this information to teachers. Figure 1. Initial View of Instructional Leader Role in the Communication of Instructional Strategy Information

Based on our hypothesis that principals would be directly involved in translating instructional strategy information to teachers, the primary research question for the study was: How and to what degree are state standards that specify instructional strategies translated into practice by educational leaders at the school level?

A semi-structured interview guide was created to elicit information from principals about issues relating to the translation of instructional strategy information specific to ELLs with disabilities. The interview guide consisted of two parts: (1) demographic information on principals, and (2) school-wide interpretation of state policy regarding instructional strategies. The questions in the second part began by asking about instructional strategy information contained in state standards and related documents. The questions then asked respondents about other sources of strategy information. The appendix contains the complete interview protocol.

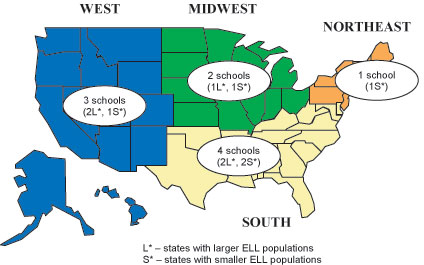

The population of ELLs with disabilities in public schools is spread widely, with limited concentrations of students in any given building. For this reason, principal participants for the study were chosen from middle and junior high schools that had demonstrated improved academic outcomes for English language learners and students with disabilities overall. In this case, school-level achievement of Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) during the 2003–2004 school year was used as an indicator of success. The research team chose this criterion because we believed that achieving AYP with ELLs and students with disabilities would entail increasing academic outcomes for ELLs with disabilities as well. NCLB legislation does not require schools to track the academic achievement of ELLs with disabilities specifically and, therefore, this information is often not available to the public. As part of this project, we hoped to capture variation in the way principals in states with large numbers of ELLs and states with small numbers of ELLs approached instruction for ELLs with disabilities. Therefore, schools were selected using a multi-stage stratified-random sampling procedure. Using data from the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, 10 states with the highest and 10 states with the lowest ELL populations were identified (n = 20). From those 20 states, 10 states were randomly drawn for inclusion in this study—5 from the states with the highest ELL populations and 5 from the states with the lowest ELL populations. In the ten selected states, a list was compiled of all the public middle and junior high schools that met AYP in the 2003–2004 school year. Schools on this list were then ranked by the percentage of ELLs attending in 2003–2004. At the same time, we noted any schools that had unusually low percentages of students with disabilities attending and eliminated these schools from our list. Finally, the top ten schools in each state were identified and the principals of these schools were invited to participate in face-to-face interviews during 2006. Within a particular state, the first principal who responded and agreed to take part in the study was selected as a participant. Teachers in the same schools were participants in a separate, but related, study investigating recommended instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities (Barrera et al., 2008). Principals and teachers were recruited as study participants at the same time. Figure 2 shows the concentration of study sites in each of the four geographic regions of the United States. Three principals worked in schools in the Western region, two worked in Midwestern schools, one worked in a Northeastern school, and four worked in Southern schools. Figure 2. Locations of School Sites

Table 1 provides detailed demographic information about the schools and districts in which the principal study was conducted, including states’ ELL population sizes, school geographic settings, grade span, total number of students, number of ELLs, and largest language groups. The geographic setting information on each school district was obtained from the National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data. We used what are now referred to as the "Old Locale Codes." Since the time of the study, locale codes have been updated to reflect changes in the definition of rural areas (NCES, 2008). The geographic setting codes indicate the schools’ location in terms of population sizes in the areas in which these schools were located (NCES, 2002). Table 1. School Sites Demographic Information for 2003–2004

Table 1 shows that the majority of principals in the study represented middle or junior high schools in mid-size central cities with a student body of approximately 800–1200 students that included sizeable groups of Spanish-speaking students. The remaining principals worked in rural schools, small town schools, large-central city schools, and schools in an urban fringe of a large city. The selected schools varied widely in the percentage of ELLs and students with disabilities attending. However, even if the percentage of ELLs attending some of the schools was small, the schools identified represented those with the largest ELL populations among all middle and junior high schools making AYP in 2003–2004 in the selected states. At the time the study began, AYP data were not yet available for the 2004–2005 school year, the year in which the study was conducted.

Participating principals came from a variety of backgrounds, as illustrated in Table 2. Among the 10 principals, there were 2 females and 8 males. These individuals had worked as principals anywhere from 2 years to 30 years, with an overall mean of 14.9 years of principal experience. One principal had been a superintendent in another state but was called on to work as a principal in a school experiencing significant change. All but one of the participants had initially been teachers and had worked in content areas such as general elementary education, math, science, technology, special education, and educational leadership in a military academy. One participant had served as the Dean of Students at a secondary school prior to becoming a principal. Principals’ length of tenure at their current school site ranged from 1 year to 14 years, with an average of 5.2 years across participants. These data do not appear to show any patterns according to whether the school was in a large or small ELL state. Table 2. Participants Demographic Information

Procedure Between January and December of 2006, a team of seven researchers went out to visit school sites in groups of three researchers per site. These team members all had experience as educators or education technical assistance providers with experience in ESL or Special Education. The teams conducted nine on-site interviews with principals at the same time as the study involving teachers was conducted (Barrera et al., 2008). One principal completed the interview by telephone at a later time due to a schedule conflict and a follow-up phone interview was conducted with one principal to clarify responses given during a face-to-face interview. The interviews ranged from 45 minutes to 110 minutes in length, depending on principals’ schedules. All interviews were digitally recorded, with permission, and later transcribed verbatim for qualitative data analysis. The NVivo qualitative data analysis software was used to organize the large amounts of verbal data.

Qualitative analysis was conducted in two stages, topic coding and thematic coding, following guidelines/common practices in qualitative data analysis (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). During topic coding, interview responses were coded and organized according to each of the five primary interview questions. Using NVivo, a member of the research team searched the interview transcripts for statements that directly answered these five questions, even if the answers occurred at other points in the interview. Table 3 lists these primary interview questions and the corresponding coding categories. Table 3. Coding Scheme: Five Coding Categories

When coding responses to question 2 we defined the term "instructional strategies" broadly to be in agreement with the way principals viewed the term. Our definition of a strategy included physical resources (e.g., computer software, laptops, textbooks, curriculum frameworks, etc.), specialized staff (e.g., translators, bilingual teachers, etc.), and supplemental services or programs (e.g., after school tutoring). During the interviews, principals often addressed other topics that they believed were related to effective instruction for ELLs with disabilities, but that were not directly included in the interview questions. We included a second stage of thematic coding to handle these other important themes and issues that arose spontaneously. Two project staff independently reviewed the interview transcripts a second time and developed a list of themes emerging from the data. The results from each reviewer were compared, using NVivo, to find areas of consensus on important themes. The following is a list of seven major themes that researchers developed based on reviewing the interview data:

After identifying these themes in the interview data, one team member coded all of the interview transcripts a second time for responses that fit the themes.

After one researcher coded the seven themes, two additional team members each recoded two interviews out of the total of ten in order to provide triangulation for reaching agreement (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). Two large ELL states and two small ELL states were selected using stratified-random sampling to ensure representation across both types of states. NVivo software provided coding comparison reports for these four states. The coding comparison reports formed the basis for repeated discussions among the three coders. The discussions highlighted areas of disagreement between the three individuals and provided an avenue to reach 100% consensus on coding decisions. Consensus was defined as two out of the three coders agreeing on every coding decision. Topic Coding Summaries of principals’ responses to the five primary interview questions are presented in this section via a series of tables along with selected quotes that illustrate points. Participants and states are not identified in this summary. However, they are numbered and referred to consistently throughout this section of the report. Issues Associated with the Instruction of ELLs with Disabilities Table 4 displays summary information on Question 1: "Would you tell us about your school and some of the issues you believe are associated with the instruction of English language learners with disabilities?" The table includes all answers that principals provided. Those responses that explicitly addressed instruction of ELLs with disabilities are marked with a check and are described in the text that follows the table. When asked about instructional issues for ELLs with disabilities, many principals answered with a multitude of concerns they had about the instruction of the ELL population as a whole. School management issues were a broad area of interest for these principals and this topic included issues such as planning instruction when the school was undergoing a rapid demographic shift in a short period of time, addressing a shortage of ESL teachers, hiring staff who could speak the students’ native languages and facilitate parent communication, and writing state accreditation plans that appropriately addressed the instruction of ELLs. Additionally, during the year in which this study took place, some of the schools that had previously been designated as achieving AYP for all students, including ELLs, changed to being identified as in need of improvement in reading or math because of low test scores for ELLs in these content areas. Some principals believed that they had the power to change the school’s status and return it to the list of those making AYP while others were less optimistic. A principal of a school in a small ELL state described his worries about the future of the school: Table 4. Responses to Question 1, ELL Instruction Issues

We’re a district in need of improvement—in reading. And it’s our ESL population that will probably forever keep us a district in need of improvement. And if we don’t make fundamental changes in how we’re going to improve their skills the future doesn’t look [good] for us….I think we’re getting better….I just see so much more that we should be doing. It all falls on how much we depend on the skills of that classroom teacher and if we can’t make that classroom teacher better, these kids aren’t going to succeed and change their attitudes. Classroom teachers, all of us, have to believe these kids can succeed. A small number of principals described issues specifically pertaining to the instruction of ELLs with disabilities. One highlighted how ELLs with disabilities in his school were largely those students without significant learning challenges. Another program existed in the district for students with more severe disabilities. This principal emphasized incorporation of all students with disabilities, including ELLs with disabilities, into mainstream instruction. He also ensured that all students with disabilities, including ELLs, received an hour of instruction in a self-contained special education classroom. A second principal discussed the challenges of determining whether an ELL with a disability should be served in ESL or special education programming. Finally, a third principal explained how the lack of qualified social workers and school psychologists had the potential to negatively affect the instruction of ELLs with disabilities. Implementation of Instructional Strategies Found in State Standards Table 5 displays summary information about principals’ responses to Question 2: "To what extent do teachers in your school implement different kinds of instructional strategies that are contained in state standards and other supporting documents?" Principals gave a variety of answers to this question that reflected their views on instructional strategies. All answers are shown in Table 5, but those that specifically referenced state standards and supporting documents are marked with a check. As shown in Table 5, a small number of principals directly referenced the content of state standards when answering this question. Most of these respondents stated that the standards contained content or broad learning goals and did not specify instructional strategies. In the schools that these principals served, teachers worked to align instruction with standards but relied on other sources for strategy information. Table 5. Responses to Question 2, Strategies Implementation

All of the respondents described instructional strategies, in the broadest sense of the word, that were being used within the school to meet the needs of students in general. ELLs with disabilities were not specifically mentioned in answers to this question, but principals did refer to ways that ELLs would benefit from strategies used for all students. Respondents varied in the degree to which they mandated instructional strategies. A few principals mentioned trying to create a school culture of shared instruction across classrooms with standardized activities that they wanted all teachers to use. For example, one principal required all teachers to use a common lesson format and to post that format so that students could learn the routine. As a school we developed certain strategies that we expect everyone to use. A certain lesson format so that there’s a warm up activity in every classroom that you go in to whether it’s from gym class to math class to art class to music class, there’s a warm up activity posted. And then there’s the lesson and then there’s a wrap up activity. And there’s specific criteria for those and that helps all of our children, especially ELLs, with having that routine in every classroom. Knowing what’s expected, you’re not walking in to a totally different learning environment. This principal led staff in creating curriculum maps based on state standards and in setting up common pacing schedules so that similar content was being taught across classrooms in grade-level instruction at the same time. In the middle of the spectrum, some principals required the use of a common curriculum or piece of instructional technology that contained strategies within it but gave teachers discretion to decide whether and how to use the related strategies. For example, one principal mentioned curriculum based on a specific model of sheltered content instruction for English language learners. This curriculum was required in ESL classes but teachers had the freedom to decide how and when to use the variety of instructional strategies suggested by the curriculum. On the opposite end of the continuum, several principals offered teachers a wide variety of instructional resources that they believed contained instructional strategies, and then gave teachers the freedom to use those resources as they thought best. These principals offered a wide variety of instructional resources such as computer technology (e.g., laptops, language labs, computerized reading or mathematics programs, etc.). One of these principals said, "I think it is important for teachers to have enough autonomy in an environment because they are the ones who are dealing with students. Each student is unique. And they have to tailor their instruction and program on a daily basis. And my goal is to provide a teacher whatever resources, training, or support that they need so that they can be the best that they can be." In most cases, principals described strategies generally and did not discuss specific ways in which the strategies were used to support grade-level content learning. For example, one principal said, "For ESL students we use visuals more. For instance, when we say, ‘I want you to speak,’ we use hand gestures, pointing, and visuals." Sources of Information Used by Teachers Table 6 displays summary information for Question 3: "On what sources of information do your teachers rely to make decisions regarding instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities? How about for English language learners in general?" Again, principals provided a wide variety of responses that are all included in Table 6. Answers that were specifically related to resources for instructing ELLs with disabilities are marked with a check. As Table 6 indicates, only one principal mentioned a source of information that gave specific guidance to teachers about instructing ELLs with disabilities. Rather, principals described broad sources of information about teaching English language learners. Respondents highlighted three main sources of general instructional strategy information for ELLs: (1) a building-level or district-level ESL specialist, (2) professional development sessions, and (3) computer technology. First, mainstream teachers often relied on an ESL or bilingual teacher or coordinator in the building as their primary source of information. For example, one principal commented: We rely highly and heavily on our ELL teacher who I think you’ve met….She does an outstanding job here….She works very well with her caseload but I think her real strength is her ability to work with mainstream staff helping them deal with her kids’ individual issues. It’s necessary for there to be a relationship there and a trust level. [She] can come in and in a very nice way really make big changes in what’s happening for her kids. Table 6. Responses to Question 3, Sources of Information

As this principal pointed out, ESL and bilingual education teachers often acted as consultants and coaches for other educators in the building, helping them understand the needs of ELLs and suggesting instructional strategies for specific students. Sometimes these teachers led staff development trainings as well and took on additional roles such as translating materials for parents and translating portions of textbooks for students. In cases where the teacher was not bilingual, an additional staff member such as a Spanish coordinator sometimes worked with the teacher to provide translated materials. Additionally, professional development sessions, either on-site or organized by the district, were a major source of information for teachers. These sessions were sometimes led by a district ESL or bilingual education specialist. For example, in one district teachers needed to learn about a new assessment for ELLs and all staff attended training led by the district ESL specialist. Alternatively, some districts organized optional training on a variety of topics relating to instruction. One principal reported that his district was offering a teacher training specifically on teaching ELLs with disabilities, but most of the training opportunities described were not specific to these students. Finally, computer technology was raised frequently as a resource for teachers. This was a theme that cut across responses to many of the interview questions. Therefore, we discuss it in more detail in the thematic coding section of this paper. Information Provided by Principals and Districts Table 7 displays summary information for Question 4: "Do you or the district provide information specifically covering instructional strategies for use with English language learners with disabilities? To what extent do teachers use this information?" The principals mentioned a variety of resources provided by the school or district and all answers are included in the table. There were no answers that explicitly referenced instructional strategy information for ELLs with disabilities. Therefore, none of the answers have a check mark next to them. Table 7. Responses to Question 4, Information Provided

Table 7 indicates that the ten principals interviewed did not mention any instructional strategy resources specifically for ELLs with disabilities that they or the district provided for teachers. The majority of principals stated that the school district’s role was to provide professional development opportunities for teachers but they did not elaborate on the content of these teacher trainings. In some cases where the district was not as involved, the principals provided those training opportunities for teachers. One principal in a small ELL state described both district and school trainings that incorporated discussion of ways to meet the needs of ELLs and students with disabilities in mainstream instruction. First, she discussed the district project on instructional strategies that had been supported by a grant: We had a five year grant in the district for professional development for regular teachers. During that five year grant, we did the training with staff across the district. But teachers could also become certified in that area and it was also paid by the grant. That made a huge difference. Through that grant, we brought in a lot of people that did a workshop for the training when we had a professional development time. The principal went on to describe how ESL and special education teachers were included in these district-wide professional development opportunities so that all teachers were thinking about ways to teach standards-based content. In addition to the district opportunities, a second layer of staff development activities on instructional strategies was provided at the school level as required by the school improvement plan. Additional Needs Regarding Instructional Strategies for ELLs with Disabilities Table 8 displays summary information on Question 5: "What additional school and classroom level needs do you, as principal, perceive regarding effective instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities?" All answers to this question are included in the table. Those that specifically addressed instruction of ELLs with disabilities are marked with a check. Table 8. Responses to Question 5, Additional School Classroom Needs

Table 8 illustrates that when principals were asked what they needed to better serve ELLs with disabilities, many of them mentioned needing additional staff, particularly ESL teachers, but did not specifically relate this need to improving instruction for ELLs with disabilities. More than one principal discussed needing to replace staff because of attrition due to issues like increasing class sizes, low pay, and changing school demographics. A principal in a remote rural area of one state described the difficulty he had getting qualified people to consider working at the school. He said: We need school psychologists here. We lack them in rural schools like us. We are constantly looking for Hispanic bilingual psychologists and special ed teachers but it is rare to find anyone interested in coming this far, you know. We are in big competition with urban schools to recruit qualified teachers so if we could offer some incentives for br anyone who is willing to move in here, I think we need extra money for that too. Other principals expressed general, non-financial needs that were not explicitly related to improving instruction for ELLs with disabilities. For example, ieache could choose from several professional development options that were offered by the district. Teachers did not always choose the option that would develop their skills for serving students with special learning needs even though such choices were available. The principal wished that these types of professional development courses on instruction could be mandatory. A second principal recognized a need for more help teaching educators how to grade ELLs in an era of school accountability. He said, "The biggest need that I think they bring is how do they grade ELLs. The regular teachers want to know, how do I grade them? I mean, the student’s speaking very little English and I’m being accountable for their progress, how do I grade them? That’s a need that I see, and more consistency that we need to have there." A third example of a need that was not directly related to funding was one principal’s wish for more collective teacher meeting time to reflect on teaching ELLs. Thematic Coding Results During the second round of coding seven themes emerged from preliminary thematic analysis of the interview transcripts: (a) outreach to parents of ELLs and ELLs with disabilities, (b) the need for staff who speak other languages, (c) school adjustment issues for ELLs and ELLs with disabilities, (d) roles played by ESL and bilingual teachers, (e) use of computers for the instruction of ELLs, (f) school-wide collaboration between staff, and (g) challenges in special education and ESL identification processes for ELLs with disabilities. These themes represented topics that were relevant to the principals who participated in the studies and often related broadly to the population of ELLs, rather than to the specific needs of ELLs with disabilities. After identifying these seven themes, we then located all of the statements that related to them in the 10 principal interview transcripts. In this section, we discuss each theme and elaborate on it using relevant quotes from selected principals. Outreach to Parents/Need for Staff Who Speak Other Languages Comments relating to themes 1 and 2, outreach to parents of ELLs and the need for staff who speak other languages, particularly Spanish, frequently occurred together in the same part of the interview. Principals in several states discussed school-wide efforts to communicate with parents of ELLs in order to better understand the students’ home cultures. The principals believed that this communication with parents would enhance students’ adjustment to school as well as their academic outcomes. Some principals, particularly in a few states with relatively small statewide ELL populations, struggled to communicate with non-English speaking parents because of a lack of bilingual staff. These principals mentioned a need for more bilingual office staff, teachers, and school psychologists to conduct special education evaluations of students. Two principals in small ELL states described how they relied on middle school students to act as translators in the absence of needed bilingual staff. One small town principal mentioned the need for parents of ELLs to be connected to the school system and the difficulty the school had in providing that connection:

In this school with few Spanish-speaking staff and a population of Spanish-speaking families with limited English skills, the principal often relied on the Spanish-speaking students to translate messages from the school to the parents. The principal jokingly referred to this practice as "dangerous." In contrast, in another small ELL state, a rural middle school principal with few local Spanish resources believed that using more English-fluent students to communicate in Spanish with less-English fluent students worked successfully:

Whether principals had sufficient native language resources or not, several of them named specific activities they had initiated in an attempt to establish some form of communication with parents of ELLs. These efforts included translated brochures, an ESL link on the school Web site, and a parent newsletter. One principal of a small town school in a large ELL state described regular written communication that included a parent newsletter that, initially, was written in English. The principal discussed his hopes to translate the newsletter in the upcoming school year through the help of an additional bilingual office specialist:

School Adjustment Issues Several principals shared anecdotes showing the difficulty ELLs in general, and refugee students in particular, experienced adjusting to the culture of schools. School adjustment difficulties were sometimes manifested as behavioral difficulties. When asked what she, as principal, perceived to be the greatest need in her building for effective instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities, one principal in a small ELL state responded by saying:

This principal emphasized the value of structured classroom and school routines so that refugee students would know the behavioral expectations. She also described the difficulty of developing consistent classroom routines and sustaining relationships between students and teachers in a school with a traditional six- or seven-period daily schedule:

In a large ELL state, an urban school principal with ELLs from a variety of language backgrounds also commented on the difficulty that staff sometimes experienced when working with immigrant and refugee students who had a history of limited formal schooling or who had experienced trauma before coming to the United States. In this principal’s opinion, there were significant challenges integrating students with emotional and behavioral needs into a large mainstream classroom:

Not every principal who mentioned school adjustment issues related them specifically to the needs of refugee or immigrant students with limited formal schooling backgrounds or a history of trauma. A principal of a predominantly Spanish-speaking small town school in a rapidly growing ELL state approached the issues of school adjustment from the angle of school violence and spoke of measures he had implemented to reduce the violence. "When I first got here, we even had school gangsters in our school. I had made five chances rule for troubling students after several meetings with teachers. It was a constant struggle to discipline students who were not used to [it] before I came in. But now it seems to be ok." Teachers’ Roles Principals viewed ESL and bilingual education specialists as front line responders who helped the larger group of ELLs face academic and personal challenges in the classroom and school. Principals spoke in glowing terms about the accomplishments of these educators who often juggled multiple demands. These teachers supported mainstream staff in meeting the instructional needs of ELLs. For example, one principal described the way the sole ESL teacher in the school balanced a complicated schedule of working in a push-in setting to diagnose and support the content language learning needs of ELLs:

Sometimes the role of specialists in supporting academic learning extended outside the regular school day. In one school that did not have a full-time ESL teacher, the principal had asked the county migrant education specialist to work with migrant students in a free after school tutoring program so that there would be a consistent staff person who understood the needs of ELLs. As previously mentioned, in addition to supporting students directly, some ESL or bilingual teachers also supported other teachers by leading school-wide staff development activities that addressed the needs of ELLs in general. One principal of a small rural middle school praised the way the ESL/bilingual teacher collaborated with the literacy specialist to deliver staff development opportunities.

A principal in a school that had experienced exponential growth in the Latino student population over the past decade relied on the district ESL specialist to train teachers in his building on implementation of the statewide assessment with ELLs. Along with balancing roles such as student advocate, classroom instructor, after school tutor and staff development leader, ESL or bilingual teachers who spoke the students’ dominant language sometimes acted as translators or interpreters. These teachers facilitated communication between the school and the family. In one case, a teacher who spoke Spanish even translated portions of textbooks for Spanish-speaking students. Use of Instructional Technology Principals mentioned the use of various kinds of instructional technology as a way to develop English language skills for ELLs, as well as to make grade-level content more accessible. Some principals had established a school-wide culture of technology use. A few principals had previously worked as instructional technology experts in schools and brought this expertise to their role as instructional leader. According to one rural school principal in a small ELL state who had a technology background, "Technology is a very, very important aspect of what I have done in the past and I’ve applied that to a lot of things we do here. So even though I am principal, I still do a lot of technology-related [things] here." Portable hand-held computers were one form of technology used by teachers in the school. The school invested money in Renaissance Learning programs such as Accelerated Math and Accelerated Reader to monitor student progress in content areas. A program called Virtu Software had also recently been purchased to help students reach targeted goals in reading, math, and writing. To facilitate these efforts, the principal had hired a technology expert specifically to work with staff on learning to use technology in the classroom. Another principal of a rural school in a small ELL state had limited access to native Spanish speaking staff but emphasized adoption of textbooks that had supporting materials in Spanish.

These Spanish-language versions of texts were available to any teacher in the building and the principal asked teachers to use the Spanish versions to supplement lectures or class notes in English. Teachers and students in one school had access to a language lab with a variety of English language materials for ELLs, but the principal expressed concern that the materials were not well used:

This principal described a computer lab that was more popular with teachers and students.

Computer access was a common topic of discussion among other principals as well. A rural school with few ELL-specific resources was able to provide laptops with full Internet access for every classroom. A crucial part of providing technology for ELLs, as well as other students, was locating sources of funding. When asked about specific needs he or his teachers had regarding effective instructional strategies for ELLs with disabilities, one principal answered:

School-Wide Collaboration Among Staff To better serve ELLs, many principals mentioned school-wide efforts to share working knowledge among teachers. Some principals had already established a time and process for collaboration, while others were in the early stages of doing so. Principals who had already designated a time for collaboration varied in the degree of structure and specificity they provided for teachers. For example, one principal established monthly faculty meetings as the time for all staff to meet and review data on student learning.

These large-group meetings did not necessarily focus on the needs of English language learners with disabilities specifically, but the principal expressed her interest in bringing results of this research study back to the staff to discuss it as a large group. Similarly, a rural school principal scheduled weekly faculty meetings that were frequently devoted to collaborative discussion of data but might involve smaller teams of faculty who would develop ideas for the larger group. He stated:

Again, these comments were not focused on planning for the specific needs of English language learners with disabilities, but presumably the needs of multiple groups of students were incorporated into the data-based discussions. Other principals had established a more open-ended time in order to support teacher collaboration. One principal had created a common day during the week for teachers to collaborate, but did not appear to have mandated the type of collaboration that needed to occur or the specific groups of students whose needs were to be discussed.

A principal of another school used staff meetings to hand out a variety of articles on best practices in assessment and instruction in the hopes of stimulating collaborative discussion.

A principal who was just beginning to establish a collaborative process to address the needs of ELLs responded:

In this school, areas that staff perceived to be the greatest need were identified and discussed. The principal added, "We communicate research areas in need in small groups. We conduct workshops. Book resources…for the teachers to become passionate." The idea of small groups of teachers from different content areas working together was referred to by another principal as "cross-pollination." This principal spoke of small collaborative groups who attended staff development sessions focused on evaluating standards-based student work and then shared with colleagues the information they had learned:

Challenges in Identifying English Language Learners with Disabilities Several respondents described the challenges of appropriately identifying ELLs with disabilities and placing them in the correct program. These principals represented both large and small ELL population states. Research participants had a variety of concerns ranging from availability of staff to identification procedures to programming decisions. Differentiating language learning processes from a disability was a common challenge. For example, one principal in a large ELL state believed that his Spanish-speaking ELLs with limited communication skills in English were often wrongly perceived by mainstream teachers as having a disability.

A second principal in a small ELL state expressed some confusion about differentiating between language learning challenges and a disability and stated "I don’t think that we’re very good at that yet." In many cases, identification of a student as an ELL appeared to be the first stage in the process, with identification of a potential disability coming at a later stage. When asked whether a student would be identified first as needing ESL or special education services a principal of a rural school in a small ELL state expressed confidence in the school’s identification procedures.

However, another principal in a small ELL state was less confident about the benefits of delaying identification of students with disabilities. When this principal was asked how an ELL with a disability would first be identified he responded that in the past the school had not identified any ELLs with disabilities because of uncertainty about the procedures.

One principal believed that separate services and systems of student identification in ESL and special education were a natural result of separate laws governing each at the federal level.

Another principal acknowledged the need to bring the two services together to provide effective instruction for ELLs with disabilities, but admitted that the school had not yet accomplished this task. This principal struggled with a model of separate service delivery that required the school to choose between ESL and special education programming for an ELL with a disability. The school created a flow chart to assist in decision making for ELLs with disabilities but the principal was concerned about achieving a balance of services for these students. This school leader’s long term goal was to work toward integrating the two programs. The issues of appropriate staffing to assist with special education placement and instruction was also on the minds of principals. Some school leaders needed greater access to qualified social workers and school psychologists who understood the process of second language acquisition and could speak the students’ native language to ensure that special education assessment was accurately identifying students with disabilities. However, having access to appropriate assessment staff did not necessarily solve all of the identification challenges. One urban school principal in a large ELL state believed that ELLs at his school were under-identified for special education services because the limited numbers of social workers and school psychologists who spoke the students’ language and understood their culture were reluctant to identify a child with a disability from that culture.

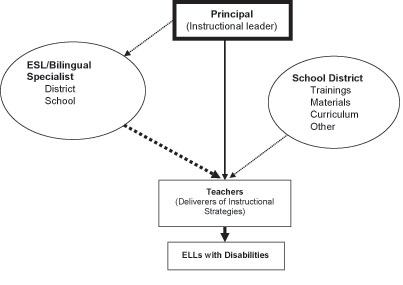

Principals interviewed for this study raised three primary issues regarding instruction for ELLs with disabilities. First, they indicated that state standards and supporting documents did not provide instructional strategy information as far as they were aware. In their view, state standards and supporting documents provided details of the content that educators needed to cover, but did not specify how to cover it. Second, appropriate identification of ELLs with disabilities was, perhaps, a larger concern for these 10 principals than ways to deliver instruction to these students. Third, ESL or bilingual education teachers often played a key role in supporting the instruction of ELLs (and, perhaps, ELLs with disabilities) in mainstream classrooms. These three issues were repeated by principals of schools in both large ELL and small ELL states. Although some of the principals could talk at a general level about addressing the needs of ELLs with disabilities, most of them talked at a broader level about addressing the needs of ELLs as a whole. The topic of ELLs as a whole may have come up more frequently because, even in large schools, there were often only a small number of ELLs with disabilities enrolled. In part, ways to appropriately instruct them in grade-level standards-based classrooms were not a particularly high priority for these 10 principals at the moment of the interviews due to the small numbers of these students in any given school. An additional factor in the lack of attention to the specific instructional needs of ELLs with disabilities may be a limited knowledge base from which principals could provide direct instructional leadership. Our initial assumption about the direct flow of instructional leadership from the principal to classroom teachers was not necessarily the case when it came to instructing this population of students with unique needs. Our small sample of principals either shared responsibility for instructional leadership of ELLs with disabilities with the district or delegated some of their authority as instructional leaders to ESL or bilingual specialists in the building. These specialists, in turn, passed on information about ELLs, and, possibly, ELLs with disabilities, to the classroom teachers. We did not ask principals whether this style of shared leadership with teachers was an intentional choice. A study conducted by Bays & Crockett (2007) identified a similar pattern of shared instructional leadership for students with disabilities within 9 schools participating in a research study. In addition, the topic of distributed leadership is increasingly more common in school leadership journals (cf. Mayrowetz, 2008; Spillane, Camburn, & Pareja, 2007; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001) suggesting that principals are adopting this style of leadership more frequently. We acknowledge that our study sample is small and findings cannot be generalized. However, based on this finding of shared instructional leadership we propose a revised version of the initial instructional leadership diagram contained in Figure 1. This revised diagram is presented in Figure 3. Figure 3. Flow of Instructional Leadership in the Communication of Instructional Strategy Information for ELLs with Disabilities

Our findings of shared instructional leadership for ELLs with disabilities raise some questions that call for additional research in this area:

As research into

standards-based instruction for ELLs

with disabilities continues, it will be

important to explore what is happening

in districts with larger populations of

these students— Albus, D., Thurlow, M., & Clapper, A. (2007). Standards-based instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 18). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Auberbach, C., & Silverstein, L. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York: New York University Press. Barrera, M., Shyyan, V., Liu, K., & Thurlow, M. (2008). Reading, mathematics, and science instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities: Insights from educators nationwide. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Barrera, M., Liu, K., Thurlow, M., & Chamberlain, S. (2006). Use of chunking and questioning aloud to improve the reading comprehension of English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 17). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Barrera, M., Liu, K., Thurlow, M., Shyyan, V., Yan, M., & Chamberlain, S. (2006). Math strategy instruction for students with disabilities who are learning English (ELLs with Disabilities Report 16). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Bays, D., & Crockett, J. (2007). Investigating instructional leadership for special education. Exceptionality, 15(3), 143-161. Catano, N., & Stronge, J. (2006). What are principals expected to do? Congruence between principal evaluation and performance standards. National Association of Secondary School Principals [NASSP] Bulletin, 90(3), 221–237. Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO]. (1996). Interstate school leaders licensure consortium: Standards for school leaders. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers. Gersten, R., Baker, S. K., Shanahan, T., Linan-Thompson, S., Collins, P., & Scarcella, R. (2007). Effective literacy and English language instruction for English learners in the elementary grades: A practice guide (NCEE 2007–4011). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved August 5, 2008, from the World Wide Web: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee Kohnert, K., Kennedy, M., Glaze, L., Kan, P., & Carney, E. (2003). Breadth and depth of diversity in Minnesota: Challenges to clinical competency. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12(3), 259–272. Layton, C., & Lock, R. (2002). Sensitizing teachers to English language learner evaluation procedures for students with learning disabilities. Teacher Education and Special Education, 25(4), 362–367. Lucas, T. (2000). Facilitating the transitions of secondary English language learners: Priorities for principals. National Association of Secondary School Principals [NASSP] Bulletin, 84(619), 2–16. Marks, H., & Nance, J. (2007). Contexts of accountability under systemic reform: Implications for principal influence on instruction and supervision. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43(1), 3–37. Mayrowetz, D. (2008). Making sense of distributed leadership: Exploring the multiple usages of the concept in the field. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(3), 424–435. Mueller, T., Singer, G., & Carranza, F. (2006). Planning and language instruction practices for students with moderate to severe disabilities who are English language learners. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, (31), 3, 242–254. National Center for Education Statistics. (2002). School locale codes 1987-2002. (Working Paper No. 2002-2). Retrieved September 15, 2008 from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2002/200202.pdf National Center for Education Statistics. (2008). Locale codes. Retrieved from July 30, 2008, from http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/commonfiles/localedescription.asp National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition. (2006). The growing number of limited English proficient students: 1995/96–2005/06. Retrieved July 30, 2008, from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/policy/states/reports/statedata/2005LEP/GrowingLEP_0506.pdf National Research Council. (1997). Educating one and all: Students with disabilities and standards-based reform. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. (P.L. 107–110). 20 U.S.C. 7801 § 9101United States Statutes at Large. Sencibaugh, J. (2007). Meta-analysis of reading comprehension interventions for students with learning disabilities: Strategies and implications. Reading Improvement, 44(1), 6–22. Smiley, P., & Salsberry, T. (2007). Effective schooling for English language learners: What elementary principals should know and do. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education, Inc. Spillane, J., Camburn, E., & Pareja, A. (2007). Taking a distributed perspective to the school principal’s workday. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 6, 1–3–125. Spillane, J., Halverson, R., & Diamond, J. (2001). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educational Researcher, 30(3) 23–28. Stecker, P., Fuchs, L., & Fuchs, D. (2005). Using curriculum-based measurement to improve student achievement: Review of research. Psychology in the Schools, 42(8), 795–819. Supovitz, J., & Poglinco, S. (2001). Instructional leadership in a standards-based reform. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education. Retrieved July 30, 2008, from http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/19/f3/9c.pdf U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2007). The Condition of Education 2007 (NCES 2007–064).Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Wakeman, S., Browder, D., Flowers, C., & Ahlgrim-Delzell, L. (2006). Principals’ knowledge of fundamental and current issues in special education. National Association of Secondary School Principals [NASSP] Bulletin, 90(2), 153–174. What Works Clearinghouse. (2007). English language learners (WWC Topic Report). Retrieved July 30, 2008, from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/ELL_TR_07_30_07.pdf Zehler, A., Fleischman, H., Hopstock, P., Stephenson, T., Pendzick, M., & Sapru, S. (2003). Descriptive study of services to LEP students and LEP students with disabilities (Volume I Research Report). Arlington, VA: Development Associates Inc. Retrieved July 30, 2008, from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/resabout/research/descriptivestudyfiles/volI_research_fulltxt.pdf Principal Interview Protocol School wide Interpretation of State Policy I) Demographic Information A) What is your previous area of teaching experience? B) How long have you been a principal? How many years have you been principal in this building? C) Tell me about your school and some of the issues you believe are associated with the instruction of English language learners with disabilities? II) Instructional Strategy Information A) To what extent do teachers in your school implement different kinds of instructional strategies that are contained in state standards and other state supporting documents? B) On what sources of information do your teachers rely to make decisions regarding instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities? How about for English language learners in general? C) Do you or the district provide information specifically to cover instructional strategies for use with English language learners with disabilities? To what extent do teachers use this information? D) What additional school and classroom level needs do you, as principal, perceive regarding effective instructional strategies for English language learners with disabilities? E) What is the best way to distribute research findings in your school or district? III. Do you have any additional comments? |