Use of Chunking and Questioning Aloud to Improve the Reading Comprehension of English Language Learners with DisabilitiesELLs with Disabilities Report 17 Manuel Barrera • Kristi Liu • Martha Thurlow • Steve Chamberlain December 2006 All rights reserved. Any or all portions of this document may be reproduced and distributed without prior permission, provided the source is cited as: Barrera, M., Liu, K., Thurlow, M., & Chamberlain, S. (2006). Use of chunking and questioning aloud to improve the reading comprehension of English language learners with disabilities(ELLs with Disabilities Report 17). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDis17/ Introduction Growing pressure from both the teaching profession (cf. Cochran-Smith & Zeichner, 2005; Levine, 2006; Walsh, Glaser, & Wilcox, 2006) and federal legislation in the No Child Left Behind Act is forcing a reexamination of instructional practices as a way to improve academic achievement of students who do not perform at grade level. Students with disabilities are receiving increased attention as one such group (National Council on Disability, 2004a, 2004b; Thurlow, Anderson, Minnema, & Hall-Lande, 2005; Thurlow, Minnema, & Treat, 2004). A growing body of research documents that English language learners (ELLs) with disabilities are a group of students with an overall level of achievement on statewide assessments that is even farther below that of the larger group of students with disabilities (Albus, Barrera, Thurlow, Guven, & Shyyan, 2004; Albus & Thurlow, 2005; Albus, Thurlow, Barrera, Guven, & Shyyan, 2004; Liu, Barrera, Thurlow, Guven, & Shyyan, 2005; Liu, Thurlow, Barrera, Guven, & Shyyan, 2005) and that of ELLs. Despite this documentation of poor performance, there are few research studies on instructional strategies specifically aimed at improving the literacy of ELLs with disabilities. Clearly, teachers need increased support in creating accessible instruction on grade-level content standards so that ELLs with disabilities can achieve academically. The need for research to support instructional practices spans all grade levels but is particularly acute at the middle school level for a variety of reasons. First, many ELLs who enter public school in the United States for the first time in middle school or junior high have experienced inconsistent schooling in their primary language (McKeon, 1994). McKeon has noted that appropriate inclusion of students with disabilities becomes more challenging at the middle school level. Teachers must find ways to teach students who, along with limited English proficiency and some learning challenges created by the disability, may not yet have a knowledge base in areas to which their peers have already been exposed. Hence, achieving grade level standards in English will be doubly challenging. A second reason for the importance of research at the middle school level is that the curriculum makes greater cognitive demands on students, especially in the expectations of reading literacy for the content areas (Klingner, Artiles, & Barletta, 2006). Finally, as the age of students increases, so does the chance of school dropout (Mikow-Porto, Humphries, Egelson, O’Connell, & Teague, 2004). High school dropout rates are around 30% for students with disabilities (National Council on Disability, 2004a); this rate is significantly higher than the rates for students without disabilities. Forty percent or more of secondary students with disabilities do not receive a high school diploma (National Council on Disability, 2004a). Research studies targeting students in grades 6-9 can be important sources of information on ways to support the grade level content learning and school completion of these students. Reading: The Gateway to Academic Success ELLs with disabilities struggle with reading and the reasons for their struggles are not well understood owing to little knowledge about the impact of disability on language development in either the first or second language (Klingner et al., 2006). Nevertheless, this difficulty in reading achievement historically has been a marker for students with learning disabilities (Bender, 2003). It may be challenging for ELLs with disabilities to learn in large general education classes (Vaughn, Klingner, & Bryant, 2001). Vaughn and her colleagues indicate that because students with the most severe reading difficulties need intense reading strategy instruction, they must have additional support services in a special education setting where there are sufficient time and resources to address student’s specific learning needs. Thus, it seems apparent that an important area of research attention is to examine the benefits of instruction in the specialized settings where small group or individualized services are provided to English language learners with disabilities. Moreover, because of the need to adapt learning situations to the specific needs of these students, it seems imperative that any examination of individualized instruction should also examine the degree to which adjustments to instruction should be made. It should also examine how different approaches to the instruction of these learners may affect learner outcomes. To add to this limited, but growing knowledge base, this report provides details about a series of single-subject research studies. The studies examine how an instructional reading strategy identified by classroom teachers could be used to improve grade-level standards-based reading achievement among English language learners with learning disabilities in individualized instructional settings. A companion report (Barrera, Liu, Yan, Chamberlain, & Thurlow, 2006) examines a similar series of studies with a mathematics instructional strategy. Background

Procedures for the single-subject studies were developed using established research methods (cf. Tawney & Gast, 1984) and involved some of the reading strategies most highly weighted in MACB group sessions. Teacher-identified strategies were chosen because of their relatively strong support and the degree to which they could be “operationalized” into a specific procedure. Strategy Definition: Chunking and Questioning The reading instructional strategy that is examined in this single-subject intervention is “Chunking and Questioning Aloud” (CQA). Teachers in MACB groups (Thurlow et al., 2004) described this strategy with two distinct parts: “The process of reading a story aloud to a group of students and stopping after certain blocks of text to ask the students specific questions about their comprehension of the story and some key features of the text” (Thurlow et al., 2004, p. 34). Operationalizing Chunking and Questioning for Use in Research The chunking and questioning strategy nominated in our research study bears a strong resemblance to what is commonly known in the teaching literature as a “Directed Reading Thinking Activity” or DRTA (Stauffer, 1969). Stauffer embedded the DRTA into a larger approach to teaching called the Language Arts Approach (or Language Experience Approach, cf. Stauffer, 1980) which involved extensive reading and writing of materials relating to a child’s experiences. According to Stauffer (1969), DRTA is a group problem solving approach to reading that teaches children comprehension skills through making predictions about the text and finding evidence to support or refute those predictions. The group-based approach provides an environment in which students behave as readers who think critically about texts. Students can then take the behaviors they practiced in the group setting and apply them to individual reading situations. In the DRTA, the teacher chooses a text at the student’s instructional level and divides it into chunks of varying lengths to maintain reader interest. The students then set the purpose for reading by making predictions about the individual chunks of text. Knowing the purpose for reading helps skilled readers determine how fast they should read a text of a particular difficulty. Students read a chunk at a time to determine whether their predictions about each chunk are correct. Finally, students use evidence from the text to prove or disprove their predictions in a group discussion. Other students respond and the teacher can guide student thinking by asking questions such as “Why do you think so?” or “Can you prove it?” Readers then have an opportunity to revise their predictions if necessary, set new predictions for the next chunk of text, and continue the process. Stauffer conducted large-scale quantitative studies into the effectiveness of the Language Arts Approach (cf. Stauffer & Hammond, 1969). He found the Language Arts Approach to be effective at improving reading comprehension as well as writing and spelling skills for students in the primary grades. However, the effects of the DRTA alone were not examined in his work. The DRTA and a teacher-led variant, Directed Listening and Thinking Aloud (DLTA) are widely recommended in the popular teaching literature. Organizations as diverse as the National Urban Alliance for Effective Education (n.d.); The Education Alliance (n.d.); The Northwest Educational Laboratory (NWREL, n.d.); and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, n.d.) mention DRTA on lists of recommended instructional strategies. The Kansas state reading standards for 4th grade refer to DRTA as a way to meet benchmarks in reading comprehension and fluency (KSDE, 2003). Test preparation materials for the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Tests in grade 4 contain references to both DRTA and DLTA as potentially useful strategies for standards-based instruction (Florida Center for Instructional Technology, 2006). Many other grass-roots organizations and teacher bulletin boards on Web sites contain a description of how teachers have used DRTA and DLTA in their classes. However, on close examination it becomes apparent that the strategy has many variations that teachers use as they adapt DRTA to particular contexts. Some versions are more structured and teacher directed. Other activities use no text at all and involve little teacher input other than directing students to fill in a chart of what they know and want to know about the topic of a book (McIntosh & Bear, 1993). All of these various strategies and activities are called DRTA but the stated purposes vary greatly from activating prior knowledge, modeling, and reducing student reading anxiety to the teaching of prediction skills in reading fiction. Our review of research documenting the effects of DRTA found three specific research studies on DRTA that assisted us in structuring an intervention. One relatively recent article by Schorzman and Cheek (2004) examined a teacher-directed version of DRTA in a general education classroom; this research may or may not have included students with disabilities. Schorzman and Cheek (2004) examined the use of DRTA in combination with a “Pre-reading plan” (cf. Langer & Nicholich, 1981) and graphic organizers (cf. Barron, 1969). Three middle school teachers in one school used a combination of strategies to teach reading and the results were compared to a control group of three other teachers at a different middle school in the district under different teaching conditions in which intensive test preparation was a focus for reading instruction. The findings of the study were mixed. The package of instructional strategies appeared to create significant pre-post student gains on a cloze test but not on a standardized reading test. Findings were complicated by issues such as logistical constraints on instructional time, teachers’ lack of willingness to change curricula for the control group setting, and a research design using intact classrooms that may have had some preexisting differences in student ability levels. In addition, standardized reading test scores may simply not be sensitive to relatively short instructional interventions. The authors did not mention whether students with disabilities were included in the classrooms involved in the research study. A second study by Bauman, Russell and Jones (1992) examined the effectiveness of a think aloud strategy on the reading comprehension of 4th grade students. Students with disabilities appear to have been excluded from the study. Although the focus of the study was on using the think aloud procedure, the experimental design included one comparison group of students using DRTA and a control group that was taught via a teacher-led guided reading process that researchers called Directed Reading Activity (DRA). The study incorporated a pre-test–post-test design with the type of intervention as the independent variable and scores from reading assessment tasks (e.g., cloze exercises, comprehension monitoring activities and error detection tasks) along with qualitative interview data as the dependent variable. Results of the study indicated that both the Think Aloud strategy and the DRTA strategy were better at increasing students’ reading comprehension skills than the traditional teacher-led method of teaching reading. However, the data were not conclusive as to which of the strategies were the most successful. On some measures it appeared that students in the Think Aloud group had greater comprehension skills while on other measures it appeared that students in the DRTA group had better comprehension skills. A third study by Draheim (1986) is a commonly referenced conference presentation on the use of the DRTA with college students. Draheim (1986) investigated the effects of four instructional strategies or combinations of strategies on student recall and use of main and surbordinate ideas in analytical essays about reading texts. The strategies included (1) Mapping, (2) Directed Reading Thinking Activity (DRTA), (3) DRTA + mapping, and (4) Reading for main ideas and underlining. This four-and-a-half week experimental study involved students in remedial education courses but did not specifically mention students with disabilities. Teachers in four sections of a remedial writing course each taught their students the use of a strategy for reading or studying text. Teachers were trained in using strategies with which they were not familiar and then were assigned to the experimental or control condition they preferred. After a period of guided instruction in the use of the instructional strategy, students were then asked to use the strategy independently to read and understand a piece of text and write an analytical essay based on it. The researcher measured the number of main and subordinate ideas students recalled after reading, and coded the essays for evidence that the ideas had been transferred into writing. Students who were taught the DRTA plus mapping strategy could recall and use the largest number of main ideas in their writing. Students in the other conditions were able to recall main ideas but were less likely to use them in their writing. The available research provided guidance in five particular areas for structuring an intervention specifically aimed at studying the effectiveness of our CQA strategy. First, the studies reviewed (Bauman et al., 1992; Draheim, 1986; Schorzman & Cheek, 2004) were conducted with groups of students who were largely not students with disabilities. Given the unique learning needs of ELLs with disabilities and their frequent need for individualized instruction, a single subject study seemed to be a more suitable research design. Single subject studies allow teachers to adapt instructional interventions to the unique needs of the student as well as to the demands of the instructional context. The results of such studies show learning under optimal conditions. Second, the studies reviewed did not isolate the use of the DRTA strategy; therefore, the results of the studies cannot speak with confidence to DRTA’s effectiveness at increasing student learning outcomes. Schorzman and Cheek (2004) studied DRTA used simultaneously with another instructional strategy while Bauman et al. (1992) included DRTA as a comparison for a different strategy in which the researchers were most interested. Given the frequency with which this instructional strategy appears to be used by educators, well-designed research on the effects of strategies like DRTA alone seems appropriate. Third, the Schorzman and Cheek article (2004) suggested the importance of allowing teachers to have choice in the curriculum used for instruction as well as the importance of incorporating extensive teacher training on the use of instructional strategies. Draheim (1986) found that teachers asked for choice in which strategy they implemented. Incorporating an element of teacher choice in the teaching of the instructional strategy seemed desirable. Fourth, Bauman et al. (1992) highlighted the importance of explicitly teaching students the components of the strategy while phasing out teacher guidance and increasing student responsibility for strategy use. The researchers followed a sequence of steps from teacher modeling to guided practice and independent practice to ensure that students could use the strategy independently. Finally, both Schorzman and Cheek (2004) and Draheim (1986) incorporated the idea of training teachers on strategy definitions. Furthermore, Schorzman and Cheek (2004) created observation checklists for assessing teacher fidelity to basic components of the strategy while Bauman et al. (1992) included observations of researcher fidelity to the strategy in a setting where researchers acted as teachers for the duration of the study. Teachers may adapt instructional strategy use over time and it is important to know exactly what teachers are doing. Training helps ensure that all teachers have a common frame of reference on what a strategy includes and observing fidelity to the strategy enables researchers to describe adaptations teachers make in a particular instructional context. The findings from this review of research helped to inform the methodology we used in implementing this study. Because of the need for a clearly defined, stepwise method, we further examined the practitioner literature for how the DRTA is operationalized, that is, defined clearly in steps for use in the classroom. We chose one form, a lesson plan by a practitioner, Padak (2006), as being closest to what teachers in our earlier research (Thurlow et al., 2004) described as the CQA strategy. Padak (2006) describes the following process:

Method Single subject research (also known as single case research) was the core methodology of this study. This method is considered experimental rather than correlational or descriptive, and its purpose is to document causal or functional relationships between independent and dependent variables as applied to research with individual subjects (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Tawney & Gast, 1984). Single case research employs within- and between-subjects comparisons to control for major threats to internal validity, and requires systematic replication to enhance external validity (Martella, Nelson, & Marchand-Martella, 1999). Choosing a Strategy An additional feature of our research was to simulate the instructional assessment and planning process by providing training to participating teachers so that they could (1) identify a student’s academic needs from her or his IEP and observed needs in meeting state academic standards, and (2) choose the appropriate strategy for a student based on these identified student needs. The research team selected three reading instructional strategies derived from among the highest supported strategies identified through the prior study using Multi-Attribute Consensus Building with classroom teachers (Thurlow et al., 2004). Factors used in choosing strategies consisted of:

Table 1. Selected Instructional Strategies

After selecting instructional strategies, the research team designed training sessions for teachers who were potential study participants at three middle schools; one in Minnesota and two in southern Texas. These sessions included the description of the theoretical basis of the study, study procedures, strategy definitions, checklists, and demonstration digital videos of each instructional intervention. Teachers had an opportunity to complete the preparation sessions and select one instructional strategy that they considered most effective and feasible for their students (ELLs with disabilities). Overall, two teachers participated in this study with four students using the chunking and questioning aloud strategy (CQA). The total number of teachers who participated in training was six; two participated in a different study reported elsewhere (Barrera et al., 2006) and two others dropped their participation during the course of the study. The teacher in Minnesota chose to work with one student of Somali background and the teacher in Texas conducted single-case studies with three students, each of Mexican-American background. To investigate the effects of the interventions, the research team used a baseline and intervention model for the strategy tested. Post intervention data were collected to examine maintenance of strategy effects. Students’ standards-based test scores, pre- and post curriculum-based measurements in basic reading skills, and ongoing performance outcomes were collected for the study. Study Participants This study involved six research participants: two teachers and four students identified with learning disabilities and limited literacy proficiency in English. The teacher working with the Somali student in Minnesota (Student S) was a Caucasian speech-language teacher working to improve the reading of a small group of students with speech-language disabilities. This teacher had over 5 years experience teaching in her classroom and conducted all reading pre-assessments and standards-based instruction for this study. The teacher working with the Mexican-American students (Students T1, T2, and T3) was Mexican-American from southern Texas and serving as a resource teacher for students with learning disabilities across a range of subjects including reading and mathematics. Although the Mexican-American teacher was a fluent bilingual in English and Spanish, instruction in both settings was conducted primarily in English. The teacher and student in Minnesota were part of a middle school (grade 6-8) in a near-suburban school district with significant recent influx of immigrant families. The teacher and students in southern Texas were from a middle school in an urban school district on the Texas-Mexico border. Students Table 2 describes the students in this study. The four students were all identified as English language learners receiving special education services for learning-related disabilities. Student S was receiving services for speech-language impairments and the three Mexican-American students were identified as having learning disabilities. However, these three students had somewhat different characteristics in academic achievement and level of English proficiency. Although student T1 appeared to have basic oral and reading proficiency in English, her overall academic achievement was significantly below grade level. Student T2 exhibited more “classic” characteristics of an ELL with a learning disability with significantly low English proficiency, reading skill, and overall academic achievement. Student T3, on the other hand, appeared to perform, at least on the state alternative assessments, at expected grade level, but his language proficiency scores seemed mixed. Student T3 was also considered to have an emotional/behavioral disorder, thus, potentially explaining some of the source of his observed learning difficulties. Table 2. Student Characteristics

*LAS-O=Language Assessment Scales-Oral; MCA= Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment; RTPE=Reading Test of Proficiency in English; SOLOM= Student Oral Language Observation Matrix; SDAA=State Developed Alternative Assessment II; TEAE= Test of Emerging Academic English1 The Texas Education Agency describes the levels of achievement on the SDAA in the following manner: “There are three achievement levels (I-III) within each instruction level…Level I: Few, if any, of the test questions were answered correctly (beginning knowledge and skills); Level II: Many of the test questions were answered correctly (developing knowledge and skills); Level III: Most or all of the test questions were answered correctly (proficient knowledge and skills)” (TEA, 2006).

Student S Student S was a Somali boy, age 11, in the 6th grade. At the time of study he was receiving special education services for a language disability. However, his special education teacher suspected that he might also have a learning disability. Appropriate Somali-language assessment instruments to document a potential learning disability were not available and the boy’s parents, who were relatively recent immigrants to the United States, did not support additional assessments for their child. The school arranged for the speech-language pathologist to provide support in reading for this student as part of a small group of other students with speech-language disabilities who also had reading difficulties. Student S’s most recent assessment data from the Minnesota Test of Emerging Academic English (TEAE) indicated that, with a score of 167, he was at the lowest of four levels in reading proficiency (Minnesota Department of Education, n.d.). His English as a Second Language teacher had rated his skills in spoken English using the Minnesota version of the Student Oral Language Observation Matrix (SOLOM © California Department of Education). Student S showed evidence of moderately strong proficiency in social language, fluency, and English vocabulary (3.0 out of 5.0 possible points). He was weaker in academic English, grammar, and pronunciation of English words (2.0 out of 5.0). If the scores for specific domains are combined an overall rating of approximately 22 to 23 points is considered fluent. Student S had an overall score of 18 points indicating limited proficiency in oral English, most likely the result of weak academic language skills. His scale score of 1070 on the Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments was most likely obtained when he was a 5th grader and places him in the lowest of five reading proficiency levels for his grade level (Albus, Barrera, et al., 2004).

Student T1 was a 15 year old Mexican-American girl in the 7th grade identified with a reading-related learning disability. On the Language Assessment Scales-Oral (LAS-O, Duncan & DeAvila, 1990) she was measured as proficient in English (LAS 4; standard score 80). Her scores on the Reading Test of Proficiency in English (RTPE) were measured at the intermediate range of proficiency at her grade level. Student T1’s standards-based reading skills were measured at instructional level four, achievement level 1 on the State Developed Alternative Assessment (SDAA). The reading test score indicated that the student answered very few of the test questions correctly and the score was three years below expected grade level. Student T2 was a 14 year old Mexican-American boy in the 7th grade identified with a reading-related learning disability. His English proficiency using the LAS-O was measured as limited English-proficient (LAS 2; standard score of 68). His reading scores (RTPE) measured at the beginning range of proficiency at his grade level and his academic achievement on the SDAA in reading was measured at instructional level 3, achievement level 1; fully four years below expected grade level at the time of testing. This score indicates that few, if any, of the items were answered correctly. Student T3 was a 15 year old Mexican-American boy in the 7th grade identified with a learning disability and an emotional/behavioral disorder. His English proficiency using the LAS-O was measured as limited English-proficient (LAS 3; standard score 73). His English reading scores (RTPE) measured at the intermediate range of proficiency at his grade level. Student T3’s overall academic achievement was measured at a 7th grade instructional level with an achievement level of 1 on the SDAA in reading. This score indicated that the student was able to complete few, if any, of the reading test questions correctly. Procedures Pre-assessment baseline data were collected at the beginning of each study and post-assessment data were collected at the end of each intervention. Pre-assessment data included the students’ state test results, IEP records, and content area test results. In addition to frequent teacher observations and reports, three observations of each student were conducted by researchers using multiple checklists and assessment protocols. Appendix A includes assessment protocols for the chosen Chunking and Questioning Aloud strategy (CQA). Measures of Progress Research-supported measures of individual learner characteristics and learner progress monitoring comprised the metrics included in this study. First, learner characteristics were derived from the latest assessment data available on each individual student. These measures included language assessment and state assessment data on academic achievement; these are individually described below for each student. Second, pre- and post-test measures were conducted using both curriculum-based measures of literal reading comprehension at the students’ grade level and a standardized curriculum-based measurement “maze” procedure (Shin, Deno, & Espin, 2000). The CBM Maze procedure is derived by taking a reading sample (in this case, reading samples from statewide reading assessments or local curriculum-based grade level reading passages) and creating a three-word choice for every 7th word (after the first sentence in the sample) in the passage. This three-word choice is designed so that the correct word choice is considered “obvious” in the context of the sentence. Hence, the maze procedure is considered practical for its administration (group or computer-based) and useful in that it is considered by practitioners to be a strong measure of both reading comprehension and word recognition (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1992). Finally, individual measures of progress were taken throughout the study by both teachers. Despite these similarities in measurement across students, the two teachers involved in this study used different approaches to measuring progress of their individual students. The Minnesota teacher of the Somali student believed that, because of the student’s unique difficulties in acquiring reading skills, it was important to teach her student at his functioning level of reading (in this case, using 3rd grade level reading materials) even as she conducted pre- and post-test measures at grade level. The teacher in Texas chose to use grade level reading materials throughout the study first, to have the students learn the strategy and then to have them use it to develop their reading skill. Additionally, the Texas teacher measured both daily work probes where the teacher provided instruction and independent comprehension probes, where the student was measured on reading comprehension questions from the reading. Both teachers measured student progress in reading comprehension at the literal level (i.e., understanding the factual and key information read). The Texas teacher collected specific measures of progress in acquiring the CQA strategy using a teacher-developed rubric with a score of 1 indicating a beginning level, 2 indicating an intermediate level, and 3 indicating mastery level in use of the CQA strategy. This strategy mastery score was collected at each probe or instructional period conducted where a content mastery score was computed. This teacher then took a “maintenance” score on content and strategy mastery at the last opportunity when the student used the CQA strategy without instruction. The Minnesota teacher did not report progress measures on the student’s acquisition of the strategy except to report anecdotally that her student required a great degree of teacher prompting in using the CQA strategy. These differences in measuring progress are reflected in the data displays for each student. Procedure for Student S The CQA strategy used with Student S was investigated using a modified baseline criteria—A1-B-A2—design (Tawney & Gast, 1984). A1 consisted of an introductory baseline with pre-tests of grade level curriculum-based measures using a district-based reading curriculum sample (6th grade) and a state-based reading sample (GE=6.9). B, the study intervention, consisted of learning and using CQA with text materials at the student’s target reading level of grade 3. Finally, A2, consisted of a concluding baseline testing the student’s proficiency with the same grade level (6th grade) used in the pre-tests, but with the added use of the CQA strategy. The study with Student S was conducted between the middle of March 2005 and the beginning of June 2005 encompassing 2.5 months. The content used in this study consisted of the Minnesota middle school academic standards for demonstrating grade level content area reading proficiency in social studies curriculum. The teacher identified the following instructional objective for Student S: given instruction in using a CQA strategy, the student will read proficiently using grade level reading samples. The criterion for performance was set at 90% accuracy and 90% comprehension based on orally-presented reading comprehension questions. At the beginning of the study, Teacher S collected pre-assessment baseline data using curriculum-based measurement protocols using state reading samples in social studies and a current grade level reading sample from the local social studies curriculum. After collecting the introductory data, the teacher initiated intervention by teaching the student the CQA strategy in a small-group setting. The procedure was taught to several students in the teacher’s resource room, but Student S needed to have more individualized attention in learning the strategy. The data collected here reflect specific probe samples from Student S only. The teacher started by defining the CQA strategy and helping Student S use it to read at his then current reading level, measured at 3rd grade. At the beginning of the process, the teacher used direct instruction to explain and model the strategy encouraging the student to follow along and demonstrate understanding of the strategy through teacher prompts. Gradually, the teacher focused on guiding the student as he became familiar with the strategy. Finally, the student was asked to use the strategy reading at grade level during the post-test curriculum-based measures on local and state-based reading samples. Procedure for Students T1, T2, & T3 The procedure used for students in Texas was similar to the Minnesota design, a baseline and post-test maintenance modified baseline criterion (A1-B-A2) with the modification that the student was allowed to use the CQA strategy without help on the maintenance probe. The content objective was selected from the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) for English Language Arts and Reading (Texas Education Agency, 1998, Chapter 110): “Reading/comprehension—the student uses a variety of strategies to comprehend a wide range of texts of increasing levels of difficulty.” Specifically, the following sub-standard was addressed:

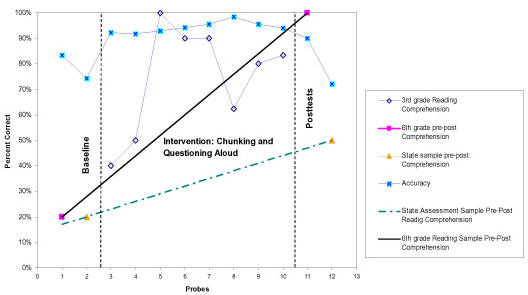

In addition to the content objective, the teacher focused on teaching the students to use the strategy independently as she worked with them. Hence, she collected two sets of data, students’ ability to solve problems and students’ ability to use the strategy independently. The teacher modeled the strategy (i.e., thinking aloud as she followed the steps), used guided practice as she checked for comprehension and utility of the strategy, provided opportunities for independent practice (i.e., homework), assessed students on mastery of the strategy and content, and provided feedback throughout. The teacher often prompted students to go to the next step after completing the previous one. Positive reinforcement (e.g., praise, gift certificate upon completion) was used throughout to motivate students. Instruction of the strategy took place over a period of 36 school days in the spring 2005 semester, with an interruption of one week for statewide testing after the first week of instruction. Results Results of each student are reported here. Those results that could be combined are aggregated for additional interpretation. Student S Results Figure 1 illustrates the progress of Student S. The numerical data are presented in Table 3. This student demonstrated significant progress on the curriculum-based classroom reading sample on teacher-administered literal comprehension questions, from a baseline score of 20% to a post-intervention score of 100%. Progress on the state-based reading sample was less dramatic registering a jump from an initial 20% score to a post-test score of 50%. During instruction, first to learn the CQA strategy and then subsequent guided use, the student’s reading accuracy remained relatively stable at the 85% to 95% range with a dip in accuracy when he was reading the state and local reading sample. As illustrated, Student S showed definite progress as he became familiar with the strategy. Figure 1. 6th Grade Somali Student Reading Comprehension

Table 3. Student S Reading Comprehension Data

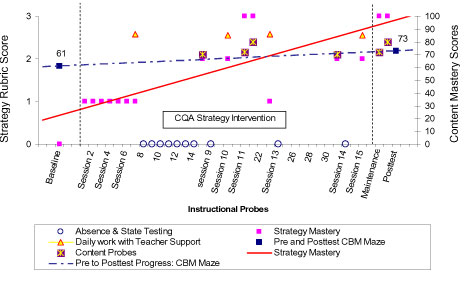

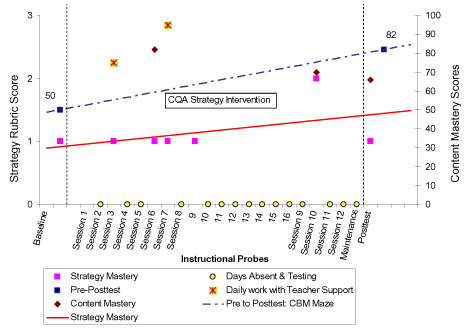

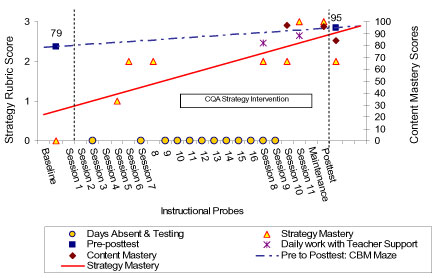

Table 4 provides the numerical data for those students T1, T2, and T3. The Texas students were assessed on content by the percent correct on teacher-delivered questions for reading comprehension at the literal level. Strategy mastery was assessed by teacher judgment using a rubric as a scale, with 1 being the lowest, where the student was judged to need the most teacher help, and 3 being the highest, where students were judged able to use the strategy independently. Pre- and post-tests using a curriculum-based measure “maze” procedure (Shin et al., 2000) indicated students’ progress before and after the CQA intervention. A maintenance check was conducted two weeks after the instructional period was completed. At the beginning of the study, the teacher determined that students had no facility in using the CQA strategy. Thus, baseline was set at zero (0). Figures 2-4 show the degree of interruption from student absences and taking statewide assessments. Table 4. Texas Students’ Reading Comprehension and Pre-Posttest Scores

Figure 2. Student T1 Strategy and Content Mastery Progress

Figure 3. Student T2 Strategy and Content Mastery Progress

Figure 4. Student T3 Strategy and Content Mastery Progress

Student T1 began slowly in developing strategy mastery until a period of absence in which she participated in statewide academic achievement testing. On her return, she began to register growth, slipping only once. By the end of the study, she began to demonstrate strong facility with the use of the strategy. Her scores on content measures maintained a steady state between probes on her daily work and independent testing. On her daily work, she averaged 85% correct on comprehension questions whereas her independent tests registered an average of 74%. Maintenance checks on strategy and content indicated she had both continued to use the strategy and maintain her average comprehension scores. A post-test using the CBM Maze procedure demonstrated an increase from her initial score of 61% at pre-test to 73% at post-test. Student T2 Results Student T2 never demonstrated adequate progress on using the CQA strategy. His strategy rubric scores only registered one score of “2”, an intermediate level of proficiency with the strategy. His daily work scores, though promising, were only measured twice owing to the student’s absence from class. His content mastery demonstrated a downward trend over the course of the study. However, his pre- to post-test maze scores showed significant progress from an initial score of 50% to a post-test score of 82%. Maintenance checks on strategy and content indicated that the student had neither mastered the strategy (a score of 1, needing significant teacher help) nor demonstrated high progress (66%) on content mastery probes of reading comprehension. Student T3 Results Student T3 performed in a manner similar to Student T1 demonstrating steady progress in learning the CQA strategy while maintaining strong reading comprehension throughout the study. Despite the absences owing to state testing (plus a few others), he scored well on strategy mastery and moderately so on content mastery during the maintenance check (the teacher noted his lack of motivation on the final day owing to his desire to complete the probe quickly). This student increased his CBM Maze score from a pre-test of 79% to a post-test of 95% comprehension. Discussion The question under study in this paper was to examine how an instructional reading strategy specifically identified by classroom teachers who work with English language learners with disabilities could be used to improve the students’ grade-level standards-based reading achievement. Because of the paucity of specifically designed evidenced-based reading research among ELLs with disabilities, we believed it important to examine how educational specialists (in this case, a special educator and speech-language specialist) might use teacher-identified reading strategies in more individualized settings such as a special education resource classroom. In both the settings under this review, the results were promising. Nevertheless, they raised many questions for further study. Our findings should be interpreted as “snapshots” on the progress of the ELLs with disabilities in this study as they begin to learn and then use the CQA strategy under the guidance of their teachers. In most cases, the students in this study improved their learning of the CQA strategy while either maintaining or slightly improving their literal reading comprehension as measured by assessments of grade-level English/Language Arts or Social Studies-based reading samples. Measurements of generalized reading ability using curriculum-based maze procedures indicated that all students increased their scores from pre- to post-tests. In the case of the Somali student, whose teacher chose to teach him the CQA strategy using text at his functional reading level (3rd grade when he was in 6th grade), his grade-level comprehension scores jumped from 20% literal comprehension to a post-test of 100% correct. However, his maze score on a state-based assessment sample showed improvement only from 20% to 50%. This student demonstrated strong progress in his functional reading level, but the differences in post-CBM scores between the locally-derived curriculum-based measure at grade level and the state-based sample indicate that there may be some difficulty translating improved functional-level reading to expected grade level reading, especially as it might be measured by a state-based standardized reading assessment. The Texas students also showed double digit percentage gains in pre- to post-test CBM Maze scores even as their teacher chose to use grade-level materials for instruction and assessment. However, in all cases, no discernible gains could be registered here on improving the students’ literal reading comprehension scores. Each of the students seemed to remain stable at their existing reading levels or showed a slight drop in performance during the study (see Student T2 results). The academic characteristics of the Texas students indicate that the relationship between language and disability across the students may have affected the students expected progress. In particular, Student T2’s previous, reading, language, and academic achievement scores were relatively weaker than the other two Texas students (see Table 1). In reviewing this student’s progress compared to his peers in this study, he never gained much facility with the CQA strategy, perhaps owing to the excessive absence, both personal and because of state testing. Despite this low performance, this student registered the largest gain on the CBM Maze pre to post-test (from 50% to 82%). Student S also seemed characterized by much more limited English and academic achievement and yet registered significant gains in at least the grade-level reading sample pre- to post-tests (as opposed to the state assessment sample tests). Thus, of the four students in the study, the seemingly lowest pre-performing students registered relatively more robust improvement during the study when measured using curriculum-based, non-standardized reading samples. Limitations of the Study The teacher/specialists involved in this study took great pains to conduct their work in the realistic settings that they and their students encountered as they, first, introduced a new skill and then sought to have the students improve their reading under, at times, distracting conditions. For example, in Texas, the teacher began the study by introducing the CQA strategy and taking initial readings of the students’ facility with it. However, this process was interrupted by the students’ participation in statewide testing. Once the students returned, the teacher was able to continue although in at least in one case, excessive absences of one of the students appear to have affected that student’s progress. The Minnesota teacher provided individualized probing and then more individualized instruction, but had to do so under conditions where she was responsible for teaching a small group of learners with similar needs. Despite these difficulties, student progress was discernible, yet not necessarily on the actual statewide standards-based assessment. These data were not available to use to factor in to our findings. We present our findings with the understanding that more clinical conditions may have improved the results. We believe it important that understanding the efficacy of instruction under realistic conditions, especially for ELLs with disabilities, is equally as important as understanding the efficacy of the methods used to achieve that instruction. Conclusions We believe this study serves a dual purpose in examining the efficacy of an instructional strategy to support the reading capabilities of English language learners with learning disabilities and in examining specific ways to support the individualized needs of their students. Moreover, our findings illustrate the vagaries in providing instruction to ELLs with disabilities often minimized or unstated in more clinical research. The CQA is a strategy identified by teachers who have worked with English language learners with disabilities (Thurlow et al., 2004) and is broadly suggested as a strategy within the research literature (Gersten, Baker, & Marks, 1998). Yet, few empirical studies have been conducted to validate such teaching strategies with ELLs or other similar groups of learners. This study adds knowledge toward a growing base of evidence in supporting the specific and unique ways that educators may improve the instruction of English language learners, especially those identified with disabilities. References Albus, D., & Thurlow, M. (2005). Beyond subgroup reporting: English language learners with disabilities in 2002-2003 online state assessment reports (ELLs with Disabilities Report 10). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport10.html Albus, D., Barrera, M., Thurlow, M., Guven, K., & Shyyan, V. (2004). 2000-2001 Participation and performance of English language learners with disabilities on Minnesota standards-based assessments (ELLs with Disabilities Report 4). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport4.html Albus, D., Thurlow, M., Barrera, M., Guven, K., & Shyyan, V. (2004). 1999-2000 Participation and performance of English language learners with disabilities on Minnesota standards-based assessments (ELLs with Disabilities Report 1). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport1.html Barrera, M., Liu, K., Yan, M., Chamberlain, S., & Thurlow, M. (2006). Math strategy instruction for students with disabilities who are learning English (ELLs with Disabilities Report 16). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Barron, F. (1969). Creative person and creative process. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc. Bauman, J., Russell, N., & Jones, L. (1992). Effects of think-aloud instruction on elementary students’ comprehension abilities. Journal of Reading Behavior, 24(2), 143-172. Bender W. (2003). Learning disabilities: Characteristics, identification, and teaching strategies (5th edition). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Campbell, D.T., & Stanley, J.C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally College Publishing Company. Cochran-Smith, M., and Zeichner, K. (eds.) (2005). Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associate, Inc. Draheim, M.E. (1986, December 2-6). Directed reading-thinking activity, conceptual mapping and underlining: Their effect on expository text recall in a writing task. Paper presented at the 36th annual meeting of the National Reading Conference. Eric Document ED285137. Duncan, S., & DeAvila, E. (1990). Language assessment scales. Monterey, CA: CTB/ McGraw Hill. Education Alliance.(n.d.).

Teaching diverse learners: Equity and

excellence for all. Reading: Grades 4-6.

Retrieved December 4, 2006 from http://www.alliance.brown.edu/tdl/elemlit/ Florida Center for Instructional Technology. (2006). Directed listening/thinking activity (DLTA) and directed reading/thinking activity (DRTA). Retrieved December 4, 2006 from http://fcit.usf .edu/fcat/references/strategies/pc1.htm Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, S. (1992).Identifying a measure for monitoring student reading progress. School Psychology Review, 21, 45-58. Gersten, R., Baker, S.K., & Marks, S.U. (1998). Teaching English-language learners with learning difficulties: Guiding principles and examples from research-based practice. Arlington, VA: The Council for Exceptional Children. Kansas State Department

of Education (KSDE). (2003). Kansas

curricular standards for reading

education: 4th grade. Retrieved December

4, 2006 from http://www.ksde.org/outcomes/ Klingner, J., Artiles, A., & Barletta, L. M. (2006). English language learners who struggle with reading: Language acquisition or LD? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(2) 108–128. Langer, J., & Nicholich, M. (1981). Prior knowledge and its relationship to comprehension. Journal of Reading Comprehension, 13(4), 373-379. Levine, A. (2006, October 31). A higher bar for future teachers. Boston Globe. Retrieved November 25, 2006 from the World Wide Web at http://www.boston.com/news/education/ higher/ articles/2006/ 10/31/a_higher_bar_for_ future teachers/ Liu, K., Barrera, M., Thurlow, M., Guven, K., & Shyyan, V. (2005). Graduation exam participation and performance (1999-2000) of English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 2). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport2.html Liu, K., Thurlow, M., Barrera, M., Guven, K., & Shyyan, V. (2005). Graduation exam participation and performance (2000-2001) of English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 3). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport3.html Martella, R. C., Nelson, J. R., & Marchand-Martella, N. E. (1999). Educational and psychological research methods: Learning to become a critical research consumer. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. McIntosh, M., & Bear, D. (1993). Directed reading-thinking activities to promote learning through reading in mathematics. Clearing House, 67(1), 40-44. McKeon, D. (1994). When meeting “common” standards is uncommonly difficult. Educational Leadership, 51(8), 45-49. Mikow-Porto, V., Humphries, S., Egelson, P., O’Connell, D., & Teague, J. (2004). English language learners in the Southeast: Research, policy & practice. Greensboro, North Carolina: SERVE. Minnesota Department of Education. (n.d.). TEAE reading and writing levels. Retrieved December 4, 2006 from http://education.state.mn.us/mde/static/000451.pdf National Council on Disability. (2004a). Improving educational outcomes for students with disabilities. Washington, DC.: Author. National Council on Disability. (2004b). National disability policy: A progress report. December 2002-December 2003. Washington, DC: Author. National Urban Alliance

for Effective Education. (n.d.).

Learning and teaching strategies. The Northwest Educational Laboratory (NWREL). (n.d.). Directed reading/thinking activity. Retrieved December 4, 2006 from http://www.nwrel.org/learns/resources/middleupper/drta.pdf Padak, N. (2006). Directed reading-thinking activity. Retrieved December 4, 2006 from http://www.deafed.net/PublishedDocs/sub/961007k.htm Schorzman, E., & Cheek, E. (2004). Structured strategy instruction: Investigating an intervention for improving sixth-graders’ reading comprehension. Reading Psychology, 25(1), 37-60. Shin, J., Deno, S.L., & Espin, C. (2000). Technical adequacy of maze task for curriculum-based measurement of reading growth. Journal of Special Education, 34(3), 164-172. Stauffer, R. G. (1969). Directing reading maturity as a cognitive process. New York: Harper & Row. Stauffer, R. G. (1980). The language-experience approach to the teaching of reading. New York: HarperCollins. Stauffer, R., & Hammond, W.D. (1969). The effectiveness of language arts and basic reading approaches to first-grade reading instruction—Extended into third grade. Reading Research Quarterly, 4(4), 468-499. Tawney, J., & Gast, D. (1984). Single subject research in special education. Columbus, Ohio: C.E. Merrill Pub. Co. Texas Education Agency (TEA). (2006). State-developed alternative assessment II: (SDAA II). Retrieved December 4, 2006 from http://www.tea.state.tx.us/student.assessment/resources/ guides/interpretive/SDAAII_06.pdf Texas Education Agency (TEA). (1998). Texas essential knowledge and skills for English language arts and reading: Subchapter B. Middle School. Section 110.23.a-10, English Language Arts and Reading, Grade 7. Retrieved December 4, 2004 from http://www.tea.state.tx.us/rules/tac/chapter110/ch110b.html Thurlow, M., Albus, D., Shyyan, V., Liu, K., & Barrera, M. (2004). Educator perceptions of instructional strategies for standards-based education of English language learners with disabilities (ELLs with Disabilities Report 7). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport7.html Thurlow, M. L., Anderson, M. E., Minnema, J. E., & Hall-Lande, J. (2005). Policymaker perspectives on the inclusion of English language learners with disabilities in statewide assessments (ELLs with Disabilities Report 8). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport8.html Thurlow, M., Minnema, J., & Treat, J. (2004). A review of 50 states’ online large-scale assessment policies: Are English language learners with disabilities considered? (ELLs with Disabilities Report 5). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Available at http://cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/ELLsDisReport5.html United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (n.d.). Teaching reading in primary schools. Retrieved December 4, 2006 from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ images/0013/001351/135162eo.pdf Vanderwood, M., Ysseldyke, J., & Thurlow, M. (1993). Consensus building: A process for selecting educational outcomes and indicators. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Vaughn, S., Klingner, J., & Bryant, D. (2001). Collaborative strategic reading as a means to enhance peer-medicated instruction for reading comprehension and content-area learning. Remedial and Special Education, 22(2), 66-74. Walsh, K., Glaser, D., & Wilcox, D. D. (2006). What education schools aren’t teaching about reading and what elementary teachers aren’t learning. Washington, DC: National Council on Teacher Quality. Retrieved December 14, 2006 from http://www.nctq.org/nctq/images/ nctq_reading_study_app.pdf Appendix

A: Protocol for Chunking and

Questioning Aloud Strategy

Teacher Lesson (describe/outline lesson here)

Teacher’s Feedback

Chunking and Questioning Aloud Student Checklist

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||